Djibouti, Tadjoura

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

An Analysis of the Afar-Somali Conflict in Ethiopia and Djibouti

Regional Dynamics of Inter-ethnic Conflicts in the Horn of Africa: An Analysis of the Afar-Somali Conflict in Ethiopia and Djibouti DISSERTATION ZUR ERLANGUNG DER GRADES DES DOKTORS DER PHILOSOPHIE DER UNIVERSTÄT HAMBURG VORGELEGT VON YASIN MOHAMMED YASIN from Assab, Ethiopia HAMBURG 2010 ii Regional Dynamics of Inter-ethnic Conflicts in the Horn of Africa: An Analysis of the Afar-Somali Conflict in Ethiopia and Djibouti by Yasin Mohammed Yasin Submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree PHILOSOPHIAE DOCTOR (POLITICAL SCIENCE) in the FACULITY OF BUSINESS, ECONOMICS AND SOCIAL SCIENCES at the UNIVERSITY OF HAMBURG Supervisors Prof. Dr. Cord Jakobeit Prof. Dr. Rainer Tetzlaff HAMBURG 15 December 2010 iii Acknowledgments First and foremost, I would like to thank my doctoral fathers Prof. Dr. Cord Jakobeit and Prof. Dr. Rainer Tetzlaff for their critical comments and kindly encouragement that made it possible for me to complete this PhD project. Particularly, Prof. Jakobeit’s invaluable assistance whenever I needed and his academic follow-up enabled me to carry out the work successfully. I therefore ask Prof. Dr. Cord Jakobeit to accept my sincere thanks. I am also grateful to Prof. Dr. Klaus Mummenhoff and the association, Verein zur Förderung äthiopischer Schüler und Studenten e. V., Osnabruck , for the enthusiastic morale and financial support offered to me in my stay in Hamburg as well as during routine travels between Addis and Hamburg. I also owe much to Dr. Wolbert Smidt for his friendly and academic guidance throughout the research and writing of this dissertation. Special thanks are reserved to the Department of Social Sciences at the University of Hamburg and the German Institute for Global and Area Studies (GIGA) that provided me comfortable environment during my research work in Hamburg. -

Ethiopians and Somalis Interviewed in Yemen

Greenland Iceland Finland Norway Sweden Estonia Latvia Denmark Lithuania Northern Ireland Canada Ireland United Belarus Kingdom Netherlands Poland Germany Belgium Czechia Ukraine Slovakia Russia Austria Switzerland Hungary Moldova France Slovenia Kazakhstan Croatia Romania Mongolia Bosnia and HerzegovinaSerbia Montenegro Bulgaria MMC East AfricaKosovo and Yemen 4Mi Snapshot - JuneGeorgia 2020 Macedonia Uzbekistan Kyrgyzstan Italy Albania Armenia Azerbaijan United States Ethiopians and Somalis Interviewed in Yemen North Portugal Greece Turkmenistan Tajikistan Korea Spain Turkey South The ‘Eastern Route’ is the mixed migration route from East Africa to the Gulf (through Overall, 60% of the respondents were from Ethiopia’s Oromia Region (n=76, 62 men and Korea Japan Yemen) and is the largest mixed migration route out of East Africa. An estimated 138,213 14Cyprus women). OromiaSyria Region is a highly populated region which hosts Ethiopia’s capital city refugees and migrants arrived in Yemen in 2019, and at least 29,643 reportedly arrived Addis Ababa.Lebanon Oromos face persecution in Ethiopia, and partner reports show that Oromos Iraq Afghanistan China Moroccobetween January and April 2020Tunisia. Ethiopians made up around 92% of the arrivals into typically make up the largest proportion of Ethiopians travelingIran through Yemen, where they Jordan Yemen in 2019 and Somalis around 8%. are particularly subject to abuse. The highest number of Somali respondents come from Israel Banadir Region (n=18), which some of the highest numbers of internally displaced people Every year, tensAlgeria of thousands of Ethiopians and Somalis travel through harsh terrain in in Africa. The capital city of Mogadishu isKuwait located in Banadir Region and areas around it Libya Egypt Nepal Djibouti and Puntland, Somalia to reach departure areas along the coastline where they host many displaced people seeking safety and jobs. -

Djibouti: Z Z Z Z Summary Points Z Z Z Z Renewal Ofdomesticpoliticallegitimacy

briefing paper page 1 Djibouti: Changing Influence in the Horn’s Strategic Hub David Styan Africa Programme | April 2013 | AFP BP 2013/01 Summary points zz Change in Djibouti’s economic and strategic options has been driven by four factors: the Ethiopian–Eritrean war of 1998–2000, the impact of Ethiopia’s economic transformation and growth upon trade; shifts in US strategy since 9/11, and the upsurge in piracy along the Gulf of Aden and Somali coasts. zz With the expansion of the US AFRICOM base, the reconfiguration of France’s military presence and the establishment of Japanese and other military facilities, Djibouti has become an international maritime and military laboratory where new forms of cooperation are being developed. zz Djibouti has accelerated plans for regional economic integration. Building on close ties with Ethiopia, existing port upgrades and electricity grid integration will be enhanced by the development of the northern port of Tadjourah. zz These strategic and economic shifts have yet to be matched by internal political reforms, and growth needs to be linked to strategies for job creation and a renewal of domestic political legitimacy. www.chathamhouse.org Djibouti: Changing Influence in the Horn’s Strategic Hub page 2 Djibouti 0 25 50 km 0 10 20 30 mi Red Sea National capital District capital Ras Doumeira Town, village B Airport, airstrip a b Wadis ERITREA a l- M International boundary a n d District boundary a b Main road Railway Moussa Ali ETHIOPIA OBOCK N11 N11 To Elidar Balho Obock N14 TADJOURA N11 N14 Gulf of Aden Tadjoura N9 Galafi Lac Assal Golfe de Tadjoura N1 N9 N9 Doraleh DJIBOUTI N1 Ghoubbet Arta N9 El Kharab DJIBOUTI N9 N1 DIKHIL N5 N1 N1 ALI SABIEH N5 N5 Abhe Bad N1 (Lac Abhe) Ali Sabieh DJIBOUTI Dikhil N5 To Dire Dawa SOMALIA/ ETHIOPIA SOMALILAND Source: United Nations Department of Field Support, Cartographic Section, Djibouti Map No. -

Djibouti Location Geography Climate

Djibouti Location This republic is located in the Northeastern part of Africa. It is located at the Bab el Mandeb Strait and links the Red Sea and Gulf of Aden. The country is named after a city called Dijbouti which was a city located at an important trade route connecting the Indian Ocean with the Mediterranean Sea and Africa with the Middle East. It can also be said that this country is located just north of the Horn of Africa.This Djibout also shares a border with Somalia and Eritrea. Geography The country has an area of about 23,200 sq. km. The distance between the country’s northern most and southern most part is 190 kms. The western most and eastern most parts are separated by 225 kms. Ethiopia borders the country to the north, west, and south, and Somalia borders the southeastern part of the country. The Gulf of Aden lies on the eastern side and the Gulf of Tadjoura extends 100 kms from the eastern part of the coast. The highest point in the country is the Moussa Ali with an elevation of 2,063 meters above sea level. The western part of the country is desert lowland with several salt lakes. Lake Abbe is the largest of the lakes which lies on the Ethiopian border. Lake Asal is the deepest lake in the country and is 153 meters deep. Climate It is hot and dry throughout the year. The summer is hotter and drier because of the desert inland winds blowing across the country. The daily temperature in winder is approximately 23-29 degrees Celsius and during summer it is 106 degree Fahrenheit. -

Migrant Smuggling: Paths from the Horn of Africa to Yemen and Saudi

Migrant smuggling Paths from the Horn of Africa to Yemen and Saudi Arabia Peter Tinti This report examines the smuggling networks facilitating irregular migration from the Horn of Africa to countries in the Arabian Peninsula, also referred to as the Gulf. In addition to analysing the structure and modus operandi of migrant smuggling networks, the author considers the extent to which these networks are involved in other forms of organised criminal activity, such as arms and narcotics trafficking. The report concludes with recommendations for policymakers and stakeholders operating in the Horn of Africa and Yemen. AFRICA IN THE WORLD REPORT 7 | NOVEMBER 2017 Introduction Key points Although it receives far less media and policy attention, the number of Foreign donors and bilateral irregular migrants travelling from the Horn of Africa to Yemen and Saudi partners should promote Arabia dwarfs the number migrating from the Horn of Africa toward Europe. general capacity-building of In 2016, a record 117 107 irregular arrivals were recorded in Yemen, 83% of relevant state institutions, which were Ethiopian. Somalis comprised the remaining 17%.1 rather than focusing on migrant smuggling, when training law- The numbers detected crossing along the same routes in 2017, close to enforcement, judiciary, and 55 000 as of the end of May,2 are lower than in 2016, but these flows still border-control staff. represent a substantial movement of people, raising several questions about human security, organised crime, regional migration management policies, Policies to counter migrant and to a lesser extent armed conflict in Yemen.3 Given the deteriorating smuggling must be country security situation in Yemen and limited monitoring in the transit countries of specific and adequately Djibouti and Somalia, it is likely that actual arrivals are considerably higher account for the social, than those recorded, with migrants also seeking to avoid detection by local economic and political context governments as well as humanitarian and aid agencies during their journey. -

Lineament Mapping in North Ghoubbet (Tadjoura, Djibouti)

REPUBLIQUE BUNDESREPUBLIK DE DJIBOUTI DEUTSCHLAND Office Djiboutien de Bundesanstalt für Développement de Geowissenschaften und l’Énergie Géothermique Rohstoffe (BGR) (ODDEG) Hannover Djibouti Regional Project Geothermal Energy East Africa Lineament Mapping in North Ghoubbet (Tadjoura, Djibouti) Alina Ermertz Remote Sensing Working Group BGR Hannover, October 2020 Lineament Mapping in North Ghoubbet (Tadjoura, Djibouti) Author Alina Ermertz (BGR) Project Number 2016.2066.5 BGR Number 05-2392 Project Partner Office Djiboutien de Développement de l’Énergie Géothermique (ODDEG) Pages 31 Place and date of issuance Hannover, October 2020 Lineament Mapping in North Ghoubbet (Tadjoura, Djibouti) Abbreviations List of figures Summary Table of Contents 1 Scope of the Work ...........................................................................................................1 2 Geothermal Exploration in the Republic of Djibouti .......................................................... 2 3 Working Area ..................................................................................................................3 4 Geology & Plate Tectonic Setting .................................................................................... 4 4.1 Geology of the Afar Triangle ..................................................................................... 4 4.2 Geology in North Ghoubbet ...................................................................................... 7 5 Lineament Analysis ...................................................................................................... -

Off the Tourist Track a New Train from the Capital “No Problem,” She Replied Brightly, Neighbor, Brought Peace to Their Without Breaking Stride

C M Y K Sxxx,2019-04-14,TR,001,Bs-4C,E1 3 SEATTLE The South Park neighborhood, on the upswing. 8 BEFORE TAKEOFF Interpreting the airlines’ boarding rules. 9 PARIS Six restaurants with delicious food and tasty prices. DISCOVERY ADVENTURE ESCAPE SUNDAY, APRIL 14, 2019 PHOTOGRAPHS BY MARCUS WESTBERG FOR THE NEW YORK TIMES Clockwise from top left: a Harar Jugol merchant; Lebu Station, the western terminus of the new train line at Addis Ababa; a convenience store in Harar Jugol; coffee, or buna in Ethiopia’s Amharic language; the air-conditioned new train; Harar Jugol, a maze of narrow alleys; and the beach in Djibouti on the Gulf of Tadjoura. Off the Tourist Track A new train from the capital “No problem,” she replied brightly, neighbor, brought peace to their without breaking stride. “A technician shared border for the first time in more of Ethiopia to the Djibouti is dealing with it.” It was only later that than 20 years. coast offers a desert journey one of our Ethiopian neighbors told us However, for every two steps for- into the Horn of Africa’s we had struck some errant livestock. ward there has been one back. The passengers — my photographer With the economic miracle stalled past, as well as its future. Marcus Westberg and I among them — by drought in 2016, and antigovern- merely shrugged. We had never kid- ment riots tearing through the Oromia By HENRY WISMAYER ded ourselves that this trip would be heartlands the same year, Ethiopia re- We were around 30 miles shy of Dire entirely without misadventure. -

The Republic of Djibouti.” (Inter- by Afar and Somali Nomadic Herds People

Grids & Datums REPUBLIC OF DJIBOUTI by Clifford J. Mugnier, C.P., C.M.S. Thanks to Lonely Planet, “Despite the inhospitable climate, Djibouti’s de Afars et Issas). The French Territory of the Afars and Issas became arid plains have been populated since the Paleolithic era, fought over independent on June 27, 1977 as the Republic of Djibouti.” (Inter- by Afar and Somali nomadic herds people. Islam spread its prayer rugs national Boundary Study No. 87 (Rev.) Djibouti – Somalia Boundary from around 825 AD in a region that was then used as grazing lands May 18, 1979, Offi ce of the Geographer, Bureau of Intelligence and by several tribes, including the Afars from eastern Ethiopia and the Research) The boundary with Ethiopia is considerably more complex, Issas from Somalia. Arab traders controlled the region until the 16th and is treated fully in International Boundary Study No. 154. century, but the Afar sultans of Obock and Tadjoura were in charge Djibouti is slightly smaller than the state of Massachusetts, and is by the time the French arrived in 1862. The French were seeking to bordered by Eritrea (113 Km), Ethiopia (337 km) (PE&RS, March 2003), counterbalance the British presence in Aden on the other side of the and Somalia (58 km). The coastline along the Red Sea is 314 km, the Bab al-Mandab Strait and, after negotiating with the sultans for the lowest point is Asal at –155 m and the highest point is Moussa Ali right to settle, they bought the place for 10,000 thalers. (2,028 m) (CIA Factbook). -

Young Rift Kinematics in the Tadjoura Rift, Western Gulf of Aden, Republic

Young rift kinematics in the Tadjoura rift, western Gulf of Aden, Republic of Djibouti Mohamed Daoud, Bernard Le Gall, René Maury, Joël Rolet, Philippe Huchon, Hervé Guillou To cite this version: Mohamed Daoud, Bernard Le Gall, René Maury, Joël Rolet, Philippe Huchon, et al.. Young rift kinematics in the Tadjoura rift, western Gulf of Aden, Republic of Djibouti. Tectonics, American Geophysical Union (AGU), 2011, 30, pp.TC1002. 10.1029/2009TC002614. insu-00558975 HAL Id: insu-00558975 https://hal-insu.archives-ouvertes.fr/insu-00558975 Submitted on 15 Aug 2011 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. TECTONICS, VOL. 30, TC1002, doi:10.1029/2009TC002614, 2011 Young rift kinematics in the Tadjoura rift, western Gulf of Aden, Republic of Djibouti Mohamed A. Daoud,1,2 Bernard Le Gall,2 René C. Maury,2 Joël Rolet,2 Philippe Huchon,3 and Hervé Guillou4 Received 23 September 2009; revised 30 June 2010; accepted 14 September 2010; published 11 January 2011. [1] The Tadjoura rift forms the westernmost edge of the various scales of times and space, and usually lead to westerly propagating Sheba ridge, between Arabia and intricate geometrical configurations. -

Rhincodon Typus) in the Gulf of Tadjoura, Djibouti

Environ Biol Fish DOI 10.1007/s10641-006-9148-7 ORIGINAL PAPER Aggregations of juvenile whale sharks (Rhincodon typus) in the Gulf of Tadjoura, Djibouti D. Rowat Æ M. G. Meekan Æ U. Engelhardt Æ B. Pardigon Æ M. Vely Received: 23 April 2006 / Accepted: 16 September 2006 Ó Springer Science+Business Media B.V. 2006 Abstract A total of 23 whale sharks were ARGOS (Splash) satellite tag for 9 d. During this identified over a 5 d period in the Arta Bay time the shark traversed to the shoreline on the region of the Gulf of Tadjora, Djibouti. Most of opposite side of the Gulf (a distance of 14 km) the sharks aggregating in this area were small and then returned to the Arta Bay area before (<4 m TL) males. Individuals were identified retracing his path to the other shore. The shark using photographs of distinctive scars and spot spent most of the daylight hours at the surface, and stripe patterns on the sides of the animals. Of while at night dives were more frequent, deeper these, 65% had scarring that was attributable to and for longer durations. boat or propeller strikes. Most of the whale sharks we encountered were feeding on dense Keywords Whale shark Á Rhincodon typus Á accumulations of plankton in shallow water just Aggregation Á Feeding off (10–200 m) the shoreline. This food source may account for the aggregation of sharks in this area. One 3 m male shark was tagged with an Introduction D. Rowat (&) Whale sharks, Rhincodon typus, are found Marine Conservation Society Seychelles, P.O. -

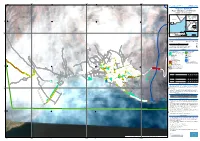

Tadjoura - DJIBOUTI Flood - Situation As of 26/11/2019 Gra Ding - Overview Ma P 01

267000 268500 270000 42°51'20"E 42°52'0"E 42°52'40"E 42°53'20"E GL IDE number: FL -2019-000156-DJ I Activa tion ID: EMS R 410 Int. Cha rter ca ll ID: N/A Product N.: 02T ADJ OUR A, v1 Tadjoura - DJIBOUTI Flood - Situation as of 26/11/2019 Gra ding - Overview ma p 01 Obock Tadjoura N " 0 ' 8 4 Red N ° Y emen " 1 0 Eritrea Sea ' 1 8 Bab el 4 ° Mandeb 1 1 0!(2 Ethiopia T a djoura Gulf of Aden Gulf of Aden ^Djibouti Djibouti S oma lia 0 0 0 0 0 0 5 5 0 0 3 3 Djibouti 01 1 1 8,5 Arta km Cartographic Information 1:6500 Full color A1, 200 dpi resolution 0 0,25 0,5 km Grid: W GS 1984 UT M Z one 38N ma p coordina te system T ick ma rks: W GS 84 geogra phica l coordina te system ± Legend Crisis Information General Information Flooded Area (26/11/2019 07:33 UT C ) Area of Interest Flood tra ce (26/11/2016 07:33 UT C) Placenames Built Up Grading ! Pla cena me Destroyed Hydrography Da ma ged R iver Possibly da ma ged S trea m Transportation grading L a ke R oa d, Destroyed Land Use - Land Cover R oa d, Da ma ged Features available in the vector package N R oa d, Possibly da ma ged " 0 2 ' 7 N Prima ry R oa d, No visible da ma ge " 4 ° 0 1 2 ' 1 7 4 L oca l R oa d, No visible da ma ge ° 1 1 Ca rt T ra ck, No visible da ma ge Consequences within the AOI Possibly Total Total in Unit of measurement Destroyed Damaged damaged affected AOI Flooded area ha 0,6 Flood trace ha 37,9 Estimated population Number of inhabitants N/A 3793 Settlements Residential No. -

Map of the Horn of Africa

40° Al Qunfudhah 45° 50° HORN OF AFRICA SAUDI ARABIA Atbara Abhā Red Sea Najrān HORN Thamūd Alghiena A OF t Sala Sa'dah b Jīzān AFRICA Nile a r Shendi a Nakfa Mersa Gulbub Af'abet Jaza'ir'- Dahlak Farasān YEMEN Khartoum ERITREAArchipelago Saywūn Sebderat Mitsiwa'e Hajjah Kassala Asmara Şan'ā Shabwah Inghel Ma'rib 15 Teseney 15 ° Barentu Mersa Fatuma (Sanaa)' ° Al Hudaydah SUDAN Adi Quala 'Atāq Ash Shihr Wad Madani Omhajer Tio Dhamār Al Mukallā Gedaref Aksum Adigrat Himora Adwa Idi Ibb Al Baydā' T Balhāf ekez W Sinnar e Mek'ele Ta'izz B Ahwar h a i b t Singar e B D a i Shaykh 'Uthmān N N n Metema l d Debark' l u e M G i i G l l e r Assab w e e e Sek'ot'a a e N n Adan (Aden) a s Gonder d rd i a l l a e e b T'ana fu Serdo Obock Gulf of Aden Caluula y Hayk Weldiya DJIBOUTI Ed Damazin Bahir Dar Tadjoura Butyaalo A Djibouti b h Guba ay Bati s Boosaaso (Bl a Saylac u Dese w Dikhil e A Ali Sabin N Karin Bure i l Ceerigaabo Xaafuun Goha A e Kurmuk b ) a Debre Mark'os Gewané y Boorama Baki Berbera 10 10 ° Mendi ETHIOPIA ° Fiche Debre Birhan Dire Dawa Hargeysa Burco Qardho Gimbi Nek'emte Addis Ababa Harer Jijiga Bandarbeyla Gidami Hagere Hiywet Mojo Boor Kigille Dembi Dolo Nazret Laascaanood Garoowe Gambela Degeh Bur Gore Gil Agaro Eyl o W Hosa'ina Asela en Akobo z Jima A Yeki Xamure ko Awasa Ginir b Shewa Gimira o W Pibor Post a Werder Gaalkacyo Sodo Goba b K'ebri Dehar Yirga 'Alem e Omo G Imi P e Wabe Shebele ib Towot s War Galoh o Abaya t r Kibre r Sogata Arba Minch' Hayk Menguist o Shilabo Ch'amo Galadi Dhuusamarreeb SOUTH SUDAN Hayk Genale