The Los Angeles

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Mapping Robert Storr

Mapping Robert Storr Author Storr, Robert Date 1994 Publisher The Museum of Modern Art: Distributed by H.N. Abrams ISBN 0870701215, 0810961407 Exhibition URL www.moma.org/calendar/exhibitions/436 The Museum of Modern Art's exhibition history— from our founding in 1929 to the present—is available online. It includes exhibition catalogues, primary documents, installation views, and an index of participating artists. MoMA © 2017 The Museum of Modern Art bk 99 £ 05?'^ £ t***>rij tuin .' tTTTTl.l-H7—1 gm*: \KN^ ( Ciji rsjn rr &n^ u *Trr» 4 ^ 4 figS w A £ MoMA Mapping Robert Storr THE MUSEUM OF MODERN ART, NEW YORK DISTRIBUTED BY HARRY N. ABRAMS, INC., NEW YORK (4 refuse Published in conjunction with the exhibition Mappingat The Museum of Modern Art, New York, October 6— tfoti h December 20, 1994, organized by Robert Storr, Curator, Department of Painting and Sculpture The exhibition is supported by AT&TNEW ART/NEW VISIONS. Additional funding is provided by the Contemporary Exhibition Fund of The Museum of Modern Art, established with gifts from Lily Auchincloss, Agnes Gund and Daniel Shapiro, and Mr. and Mrs. Ronald S. Lauder. This publication is supported in part by a grant from The Junior Associates of The Museum of Modern Art. Produced by the Department of Publications The Museum of Modern Art, New York Osa Brown, Director of Publications Edited by Alexandra Bonfante-Warren Designed by Jean Garrett Production by Marc Sapir Printed by Hull Printing Bound by Mueller Trade Bindery Copyright © 1994 by The Museum of Modern Art, New York Certain illustrations are covered by claims to copyright cited in the Photograph Credits. -

Edward Ruscha

Edward Ruscha Born December 16, 1937, Omaha, Nebraska. Moved to Oklahoma City, Oklahoma, 1941. Moved to California in 1956. Currently lives in Culver City, CA. Education Chouinard Art Institute, Los Angeles, 1956 - 1960 Awards & Grants 1967 National Council on the Arts Grant 1969 National Endowment for the Arts Grant Tamarind Lithography Workshop Fellowship 1971 Guggenheim Foundation Fellowship 1974 Skowhegan School of Painting and Sculpture Award in Graphics 1988 Graphic Arts Council of the Los Angeles County Museum of Art, Achievement in Printmaking Award 1995 California Arts Council, Governor’s Awards for the Arts, Achievement in Visual Arts Award 2009 Artistic Excellence Award, Americans for the Arts Selected Exhibitions 1969 La Jolla Museum of Art, California 1972 University of California, Santa Cruz (Jan.17-Feb.11) Catalogue Minneapolis Institute of Arts, Minneapolis, Minnesota (April-May) 1973 Books by Edward Ruscha. University of California, San Diego (January 9- 26) WORKS BY EDWARD RUSCHA FROM THE COLLECTION OF PAUL J. SCHUPF, Picker Gallery, Colgate University, Hamilton, New York (November 2 - December 2) WORKS BY EDWARD RUSCHA. Francoise Lambert, Milan, Italy. EDWARD RUSCHA PRINTS / BOOKS, Root Art Center, Hamilton College, Clinton, New York (Jan. 3 - 23) 1974 FILM PREMIUM AND BOOKS, Contemporary Graphics Center, Santa Barbara Museum of Art, Santa Barbara, California (Oct. 29 - Dec. 5) Golden West College, Huntington Beach, California EDWARD RUSCHA, PRINTS / PUBLICATIONS 1962-74. The Arts Council of Great Britain, traveling exhibition to twelve Arts Council member galleries; Northern Kentucky State University, Highland Heights, Kentucky; Los Angeles. Catalog. ED RUSCHA: PRINTS, Northern Kentucky State University, Highland Height, Kentucky AUSTIN ART PROJECTS RING. -

Millard Sheets Was Raised and Became Sensitive to California’S Agricultural Lifestyle

YYYYYYYYYYYYYYYYYYYYYYYYYYYYYYYYYYYYYYYY I A A R R N T O F C I L L U A B C CALIFORNIA ART CLUB NEWSLETTER Documenting California’s Traditional Arts Heritage for More Than 100 Years e s 9 t a 9 0 b lis h e d 1 attracted 49,000 visitors. It was in this rural environment that Millard Sheets was raised and became sensitive to California’s agricultural lifestyle. Millard Sheets’ mother died in childbirth. His father, John Sheets, was deeply distraught and unable to raise his son on his own. Millard was sent to live with his maternal grandparents, Louis and Emma Owen, on their neighbouring horse ranch. His grandmother, at age thirty-nine, and grandfather, at age forty, were still relatively young. Additionally, with two of their four youngest daughters, ages ten and fourteen, living at home, family life appeared normal. His grandfather, whom Millard would call “father,” was an accomplished horseman and would bring horses from Illinois to race against Elias Jackson “Lucky” Baldwin (1828-1909) at Baldwin’s “Santa Anita Stable,” later to become Santa Anita Park. The older of Millard’s two aunts babysat him and kept him occupied Abandoned, 1934 with doing drawings. Oil on canvas 39 5/80 3 490 Collection of E. Gene Crain he magic of making T pictures became a fascination to Sheets, as he would later explain in Millard Sheets: an October 28, 1986 interview conducted A California Visionary by Paul Karlstrom for the Archives of American Art, Smithsonian by Gordon T. McClelland and Elaine Adams Institution: “When I was about ten, I found out erhaps more than any miles east of downtown Los Angeles. -

GUILLERMO KUITCA Biography

SPERONE WESTWATER 257 Bowery New York 10002 T + 1 212 999 7337 F + 1 212 999 7338 www.speronewestwater.com GUILLERMO KUITCA Biography 1961 Born Buenos Aires, Argentina. Lives and works in Buenos Aires. Awards 2018 Chevalier de l’Ordre des Arts et des Lettres, France Selected Solo Exhibitions 1974 Galeria Lirolay, Buenos Aires 1978 Galeria Christel K., Buenos Aires 1980 Fundacion San Telmo, Buenos Aires 1984 Galeria Del Retiro, Buenos Aires 1985 Elizabeth Franck Gallery, Knokke-Le-Zoute, Belgium (catalogue) 1986 “Guillermo Kuitca: Siete Ultimas Canciones,” Galeria del Retiro, Buenos Aires Thomas Cohn Arte Contemporanea, Rio de Janeiro 1987 Galeria del Retiro, ARCO, Feria Internacional de Arte Contemporanea, Madrid (catalogue) Galeria Paulo Figueiredo, Sao Paulo 1989 Thomas Cohn Arte Contemporanea, Rio de Janeiro Galeria Atma, San Jose, Costa Rica Argentina Pavilion, “XVIII Bienal,” Sao Paulo (catalogue) 1990 Annina Nosei Gallery, New York Galerie Barbara Farber, Amsterdam (catalogue) “Guillermo Kuitca,” Kunsthalle Basel, Basel Thomas Solomon’s Garage, Los Angeles “Guillermo Kuitca,” Witte de With Center for Contemporary Art, Rotterdam (catalogue) “Guillermo Kuitca,” Stadtisches Museum, Mulheim 1990-91 Galleria Gian Enzo Sperone, Rome, 14 December 1990 – 15 January 1991 (catalogue) 1991 Annina Nosei Gallery, New York (catalogue) Galerie Barbara Farber, Amsterdam 1991-92 “Projects 30: Guillermo Kuitca,” The Museum of Modern Art, New York, 13 September – 29 October 1991; Newport Harbor Art Museum, Newport Beach, 7 February – 29 March 1992; -

Colson Biography

2525 Michigan Ave., Unit B2, Santa Monica, CA USA 90404 T/ 310 264 5988 F/ 310 828 2532 www.patrickpainter.com GREG COLSON BIOGRAPHY Born Seattle, WA. BA, California State University, Bakersfield, CA. MFA, Claremont Graduate School, CA. Lives and works in Venice, CA. SELECTED SOLO EXHIBITIONS 2013 Patrick Painter Inc, Santa Monica, CA. 2012 Patrick Painter Inc, Santa Monica, CA. Baldwin Gallery, Aspen, CO. 2010 William Griffin Gallery, Santa Monica, CA. 2008 William Griffin Gallery, Santa Monica, CA. 2007 William Griffin Gallery, Santa Monica, CA. 2006 Baldwin Gallery, Aspen, CO. 2005 Griffin Contemporary, Santa Monica, CA. 2004 Griffin Contemporary, Santa Monica, CA. 2002 Sprovieri, London, England Art Affairs, Amsterdam, The Netherlands Baldwin Gallery, Aspen, CO. 2001 Sperone Westwater, New York, N.Y. Galleria Cardi, Milan, Italy Griffin Contemporary, Venice, CA. 1999 John Berggruen Gallery, San Francisco, CA. Gian Enzo Sperone, Rome, Italy Griffin Contemporary, Venice, CA. 1998 Milleventi, Milan, Italy Griffin Contemporary, Venice, CA. 1997 Angles Gallery, Santa Monica, CA. 1996 Krannert Art Museum, University of Illinois, Urbana-Champaign 1995 Angles Gallery, Santa Monica, CA. 1994 Kunsthalle Lophem, Bruges, Belgium Sperone Westwater, New York, N.Y. 1993 Angles Gallery, Santa Monica, CA. 2525 Michigan Ave., Unit B2, Santa Monica, CA USA 90404 T/ 310 264 5988 F/ 310 828 2532 www.patrickpainter.com 1992 Gian Enzo Sperone, Rome, Italy 1991 Konrad Fischer, Dusseldorf, Germany Sperone Westwater, New York, N.Y. 1990 Angles Gallery, Santa Monica, CA. Sperone Westwater, New York, N.Y. 1988 Angles Gallery, Santa Monica, CA. Lannan Museum, Lake Worth, FL. 1987 Angles Gallery, Santa Monica, CA. -

Documenta 5 Working Checklist

HARALD SZEEMANN: DOCUMENTA 5 Traveling Exhibition Checklist Please note: This is a working checklist. Dates, titles, media, and dimensions may change. Artwork ICI No. 1 Art & Language Alternate Map for Documenta (Based on Citation A) / Documenta Memorandum (Indexing), 1972 Two-sided poster produced by Art & Language in conjunction with Documenta 5; offset-printed; black-and- white 28.5 x 20 in. (72.5 x 60 cm) Poster credited to Terry Atkinson, David Bainbridge, Ian Burn, Michael Baldwin, Charles Harrison, Harold Hurrrell, Joseph Kosuth, and Mel Ramsden. ICI No. 2 Joseph Beuys aus / from Saltoarte (aka: How the Dictatorship of the Parties Can Overcome), 1975 1 bag and 3 printed elements; The bag was first issued in used by Beuys in several actions and distributed by Beuys at Documenta 5. The bag was reprinted in Spanish by CAYC, Buenos Aires, in a smaller format and distrbuted illegally. Orginally published by Galerie art intermedai, Köln, in 1971, this copy is from the French edition published by POUR. Contains one double sheet with photos from the action "Coyote," "one sheet with photos from the action "Titus / Iphigenia," and one sheet reprinting "Piece 17." 16 ! x 11 " in. (41.5 x 29 cm) ICI No. 3 Edward Ruscha Documenta 5, 1972 Poster 33 x 23 " in. (84.3 x 60 cm) ICI /Documenta 5 Checklist page 1 of 13 ICI No. 4 Lawrence Weiner A Primer, 1972 Artists' book, letterpress, black-and-white 5 # x 4 in. (14.6 x 10.5 cm) Documenta Catalogue & Guide ICI No. 5 Harald Szeemann, Arnold Bode, Karlheinz Braun, Bazon Brock, Peter Iden, Alexander Kluge, Edward Ruscha Documenta 5, 1972 Exhibition catalogue, offset-printed, black-and-white & color, featuring a screenprinted cover designed by Edward Ruscha. -

A Guide to Estate Planning Considerations for Art Collectors

The Art of Planning for the Collector: A Guide to Estate Planning Considerations for Art Collectors Von E. Sanborn, Esq. Day Pitney LLP, NYC Darren M. Wallace, Esq. Day Pitney LLP, Greenwich, CT Rebecca A. Lockwood, Esq. Sotheby's, NYC NEW YORK STATE BAR ASSOCIATION TRUSTS & ESTATES LAW SECTION SPRING MEETING, MAY 3-6, 2018, SEA ISLAND, GEORGIA ARTFUL CONSIDERATIONS Von E. Sanborn, Esq. Darren M. Wallace, Esq. Rebecca A. Lockwood, Esq. I. STATUS OF THE ART MARKET a. Estate planning perspective. i. Valuation issues. ii. Family considerations. 1. Use and allocation. 2. Record keeping (provenance and authenticity) 3. Investment considerations (art as an alternative “investment class”) 4. Maintenance and security 5. Ownership structure (outright v. trust v. entity) 6. Charitable considerations b. Tax planning perspective (based on the Art Advisory Panel of the Commissioner of the Internal Revenue (the “Art Panel”) – The Annual Summary Report for the Fiscal Year 2016. i. When a tax return is audited and the return includes an appraisal of a single work of art or cultural property valued at $50,000 or more, the agent or appeals officer may refer the case to the Art Panel. ii. The Art Panel is composed of up to 25 members who serve without compensation. They are renowned art experts including dealers, advisors and curators. iii. The Art Panel met twice and reviewed 555 items on 63 taxpayer cases. iv. The average claimed value for an item reviewed by the Art Panel was $906,550. v. In 2016, the Art Panel recommended accepting value of 222 items or 40% of the items. -

BRUNA STUDE PUBLIC COLLECTIONS Hawaii State

BRUNA STUDE PUBLIC COLLECTIONS Hawaii State Foundation for Culture and the Arts, Honolulu, Hawai`i The Contemporary Museum, [Honolulu Museum Of Art] Honolulu, Hawai`i The Honolulu Academy of Arts, [Honolulu Museum Of Art] Honolulu, Hawai`i Bibliothèque Nationale de France, Paris, France SOLO EXHIBITIONS 2016 Honolulu Museum of Art, at FHC Honolulu, Hawai`i 2015 Shark Fin Soup, Alfstad& Contemporary, Sarasota, FL 2013 Maui Arts & Cultural Center (MACC), Maui, Hawai`i 2008 Kaua`i Museum, Lihue, Hawai`i 2007 TIMESPACE, Hanapepe, Kauai, Hawai`i 2006 Sulkin/Secant Gallery, Bergamot Station Art Center, Santa Monica, California SELECTED GROUP EXHIBITIONS 2015 Change & Continuity, Hawai`i State Art Museum, Honolulu, Hawai`i Oil + Water, galerie 103, Kaua`i, Hawai`i 2014 PRINT, PAPER + SANDBOX, galerie 103, Kaua`i, Hawaii 2013 Grand Prix De La Decouverte, Paris, France Uniques, Maui Arts & Cultural Center (MACC), Maui, Hawai`i 2012 Fish Out of Water, galerie 103, Kaua`i, Hawai`i Biennial of Hawai`i Artists X, Spalding House, Honolulu Museum of Art Hawai`i, Curator: Inger Tully, Honolulu, Hawai`i 2011 Artists of Hawai`i 2011, 59th Bienniall Juried Exhibition, The Honolulu Academy of Arts, Honolulu, Hawai`i 2010 Winter Kunstkammer - Part II, Walter Randel Gallery, New York, NY 2009 20 Going On 21: Honoring the Past, Celebrating the Present The Contemporary Museum, Honolulu, Hawai`i DREAMSCAPES, LOOK Gallery, Los Angeles, California Artists of Hawai`i 2009, 58th Biennial Juried Exhibition, The Honolulu Academy of Arts, Honolulu, Hawai`i The Art Studio -

Annual Report

09 annual report | 2009 annual report 2009 annual report 4 Board of Trustees 4 Committees of the Board of Trustees 7 President and Chairman’s Report 8 Director’s Report 11 Curatorial Report 15 Exhibitions 15 Traveling Exhibitions 16 Publications 17 Loans 19 Acquisitions 47 Attendance 48 Education and Public Programs 49 Year in Review 54 Development 57 Donors 67 Support Groups 71 Support Group Officers 74 Staff 76 Financial Report/Statements cover Beth Lipman, Laid Table (Still Life with Metal Pitcher), 2007. Purchase, Jill and Jack Pelisek Endowment, Jack Pelisek Funds, and various donors by exchange. Full credit listing on p. 29. left Evan Baden, Lila with Nintendo DS, 2007. Purchase, with funds from the Photography Council. Full credit listing on p. 28. Unless otherwise noted, all photographs of works in the Collection are by John R. Glembin. board of trustees Through August 31, 2009 BOARD OF TRUSTEES auxiliary Christine Symchych Photography A. Raymond Kehm W. Kent Velde spokespersons Frederick Vogel III Committee Gail A. Lione Chairman Catharine D. Malloy Robert A. Wagner Kevin Miyazaki Joan Lubar Raymond R. Krueger President, Collectors’ Hope Melamed Winter Chair Marianne Lubar Linda Marcus President Corner Carol Lewensohn Jill G. Pelisek Carol Bessler acquisitions and Vice Chair Betty Ewens Quadracci collections Dorothy M. Stadler President, Garden Club Secretary committee Barbara Ciurej Mary Strohmaier Danny L. Cunningham subcommittees George A. Evans, Jr. F. William Haberman Treasurer COMMITTEES OF THE Annual Campaign BOARD OF TRUSTEES Decorative Arts Lindsay Lochman Committee Frederic G. Friedman Committee Madeleine Lubar Jill G. Pelisek Assistant Secretary and executive committee Constance Godfrey Marianne Lubar Chair Legal Counsel Raymond R. -

For Immediate Release

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE: MEDIA CONTACTS: Carlotta Stankiewicz, 512.475.6784, [email protected] Penny Snyder, 512.471.0241, [email protected] Blanton Museum of Art Presents Ed Ruscha: Drum Skins New Body of Work Explores Southwestern-Inspired Vernacular AUSTIN, TX—December 19, 2019—The Blanton Museum of Art will present Ed Ruscha: Drum Skins in its Contemporary Project gallery from January 11 to July 12, 2020. The exhibition will debut a new body of more than a dozen round paintings made between 2017 and 2019 by the iconic American artist known for his use of language. “We are honored to present a new body of work by one of today’s most significant artists, Ed Ruscha, in the Blanton’s Contemporary Project, a rotating program for innovative work,” said Blanton director Simone Wicha. “Drum Skins brings Ruscha’s distinctive observations about American vernacular and culture to a new medium. With bold typography, allusions to music, and Southwestern speech, Drum Skins is certain to appeal to our audiences here in Austin.” The installation includes 13 text-based works painted on drumheads, which Ruscha has collected over the past 40 years. Most of the paintings feature phrases with double and triple negatives such as “Not Never,” “I Can’t Find My Keys Nowhere,” and “I Don’t Hardly Disbelieve It.” Ruscha attributes these phrases to spending his childhood in Oklahoma, noting that “I grew up with people that spoke this way.…I was very acutely aware of it and amused by it.” They are all printed in his signature font, which he refers to as “Boy Scout Utility Modern.” Several feature phrases overlaid on a mountain, a common visual motif in Ruscha’s works. -

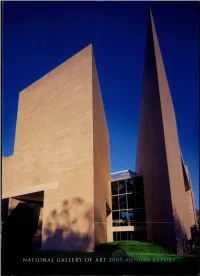

Annual Report 2005

NATIONAL GALLERY BOARD OF TRUSTEES (as of 30 September 2005) Victoria P. Sant John C. Fontaine Chairman Chair Earl A. Powell III Frederick W. Beinecke Robert F. Erburu Heidi L. Berry John C. Fontaine W. Russell G. Byers, Jr. Sharon P. Rockefeller Melvin S. Cohen John Wilmerding Edwin L. Cox Robert W. Duemling James T. Dyke Victoria P. Sant Barney A. Ebsworth Chairman Mark D. Ein John W. Snow Gregory W. Fazakerley Secretary of the Treasury Doris Fisher Robert F. Erburu Victoria P. Sant Robert F. Erburu Aaron I. Fleischman Chairman President John C. Fontaine Juliet C. Folger Sharon P. Rockefeller John Freidenrich John Wilmerding Marina K. French Morton Funger Lenore Greenberg Robert F. Erburu Rose Ellen Meyerhoff Greene Chairman Richard C. Hedreen John W. Snow Eric H. Holder, Jr. Secretary of the Treasury Victoria P. Sant Robert J. Hurst Alberto Ibarguen John C. Fontaine Betsy K. Karel Sharon P. Rockefeller Linda H. Kaufman John Wilmerding James V. Kimsey Mark J. Kington Robert L. Kirk Ruth Carter Stevenson Leonard A. Lauder Alexander M. Laughlin Alexander M. Laughlin Robert H. Smith LaSalle D. Leffall Julian Ganz, Jr. Joyce Menschel David O. Maxwell Harvey S. Shipley Miller Diane A. Nixon John Wilmerding John G. Roberts, Jr. John G. Pappajohn Chief Justice of the Victoria P. Sant United States President Sally Engelhard Pingree Earl A. Powell III Diana Prince Director Mitchell P. Rales Alan Shestack Catherine B. Reynolds Deputy Director David M. Rubenstein Elizabeth Cropper RogerW. Sant Dean, Center for Advanced Study in the Visual Arts B. Francis Saul II Darrell R. Willson Thomas A. -

Patssi Valdez Los Angeles, California B.F.A. Otis Art Institute, Los Angeles, CA Parsons School of Design, New York, NY

Patssi Valdez Los Angeles, California B.F.A. Otis Art Institute, Los Angeles, CA Parsons School of Design, New York, NY Museum Solo Exhibitions 1999 A Precarious Comfort, The Mexican Museum, San Francisco, CA; Laguna Art Museum, CA (Touring Exhibition) 1995 Patssi Valdez: A Room of One’s Own, San Jose Museum of Art, CA Museum Group Exhibitions 2018 Bridges in Time of Walls: Chicano/Mexican Art from Los Angeles to Mexico City. Pacific Standard Time: LA/LA. Traveling Exhibition through 2020. Museo de Arte Carrillo Gil, Mexico City, Mexico. La Gran Galeria, Centro Cultural de Acapulco, Acapulco, Mexico; Museo de los Pintores, Oaxaca de Juarez, Mexico; Museo de las Artes de la Universidad de Guadalajara, Guadalajara, Mexico; Centro Cultural Tijuana, Tijuana, Mexico 2017 Axis Mundo: Queer Networks in Chicano L.A. Pacific Standard Time: LA/LA. Traveling Exhibition through 2020. MOCA Pacific Design Center, West Hollywood, CA. The Hunter College Art Galleries New York, NY; The Gund Gallery at Kenyon College, Gambier, OH; Lawndale Art Center, Houston, TX; Vicki Myhren Gallery, Denver, CO; Williams College of Museum of Art, Williamstown, MA; Marjorie Barrick Museum of Art, Las Vegas, NV 2017 Judithe Hernández and Patssi Valdez: One Path Two Journeys. Pacific Standard Time: LA/LA, Millard Sheets Art Center, Pomona, CA. 2017 Radical Women: Latin American Art, 1960-1985. Pacific Standard Time: LA/LA, Pomona, CA. Hammer Museum, Los Angeles, CA. Brooklyn Museum, Brooklyn, NY. 2015 Take 10: The Past Decade of Collecting by Cheech Marin, Mesa Contemporary