Accessible Cell Phones

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

ABC's of Ios: a Voiceover Manual for Toddlers and Beyond!

. ABC’s of iOS: A VoiceOver Manual for Toddlers and Beyond! A collaboration between Diane Brauner Educational Assistive Technology Consultant COMS and CNIB Foundation. Copyright © 2018 CNIB. All rights reserved, including the right to reproduce this manual or portions thereof in any form whatsoever without permission. For information, contact [email protected]. Diane Brauner Diane is an educational accessibility consultant collaborating with various educational groups and app developers. She splits her time between managing the Perkins eLearning website, Paths to Technology, presenting workshops on a national level and working on accessibility-related projects. Diane’s personal mission is to support developers and educators in creating and teaching accessible educational tools which enable students with visual impairments to flourish in the 21st century classroom. Diane has 25+ years as a Certified Orientation and Mobility Specialist (COMS), working primarily with preschool and school-age students. She also holds a Bachelor of Science in Rehabilitation and Elementary Education with certificates in Deaf and Severely Hard of Hearing and Visual Impairments. CNIB Celebrating 100 years in 2018, the CNIB Foundation is a non-profit organization driven to change what it is to be blind today. We work with the sight loss community in a number of ways, providing programs and powerful advocacy that empower people impacted by blindness to live their dreams and tear down barriers to inclusion. Through community consultations and in our day to -

VPAT™ for Apple Ipad Pro (12.9-Inch)

VPAT™ for Apple iPad Pro (12.9-inch) The following Voluntary Product Accessibility information refers to the Apple iPad Pro (12.9-inch) running iOS 9 or later. For more information on the accessibility features of the iPad Pro and to learn more about iPad Pro features, visit http://www.apple.com/ipad- pro and http://www.apple.com/accessibility iPad Pro (12.9-inch) referred to as iPad Pro below. VPAT™ Voluntary Product Accessibility Template Summary Table Criteria Supporting Features Remarks and Explanations Section 1194.21 Software Applications and Operating Systems Not applicable Section 1194.22 Web-based Internet Information and Applications Not applicable Does not apply—accessibility features consistent Section 1194.23 Telecommunications Products Please refer to the attached VPAT with standards nonetheless noted below. Section 1194.24 Video and Multi-media Products Not applicable Does not apply—accessibility features consistent Section 1194.25 Self-Contained, Closed Products Please refer to the attached VPAT with standards nonetheless noted below. Section 1194.26 Desktop and Portable Computers Not applicable Section 1194.31 Functional Performance Criteria Please refer to the attached VPAT Section 1194.41 Information, Documentation and Support Please refer to the attached VPAT iPad Pro (12.9-inch) VPAT (10.2015) Page 1 of 9 Section 1194.23 Telecommunications products – Detail Criteria Supporting Features Remarks and Explanations (a) Telecommunications products or systems which Not applicable provide a function allowing voice communication and which do not themselves provide a TTY functionality shall provide a standard non-acoustic connection point for TTYs. Microphones shall be capable of being turned on and off to allow the user to intermix speech with TTY use. -

Adriane-Manual – Wikibooks

Adriane-Manual – Wikibooks Adriane-Manual Notes to this wikibook Target group: Users of the ADRIANE (http://knopper.net/knoppix-adriane /)-Systems as well as people who want to install the system, configure or provide training to. Learning: The user should be enabled, to use the system independently and without sighted assistance and to work productively with the installed programs and services. This book is a "reference book" for a user in which he takes aid to individual tasks. The technician will get instructions for the installation and configuration of the system, so that he can configure it to meet the needs of the user. Trainers should be enabled to understand easily and to explain the system to users so that they can learn how to use it in a short time without help. Contact: Klaus Knopper Are Co authors currently wanted? Yes, in prior consultation with the contact person to coordinate the writing of individual chapters, please. Guidelines for co authors: see above. A clear distinction would be desirable between 'technical part' and 'User part'. Topic description The user part of the book deals with the use of programs that are included with Adriane, as well as the operation of the screen reader. The technical part explains the installation and configuration of Adriane, especially the connection of Braille lines, set-up of internet access, configuration of the mail program etc. Inhaltsverzeichnis 1 Introduction 2 Working with Adriane 2.1 Start and help 2.2 Individual menu system 2.3 Voice output functions 2.4 Programs in Adriane 2.4.1 -

Vizlens: a Robust and Interactive Screen Reader for Interfaces in The

VizLens: A Robust and Interactive Screen Reader for Interfaces in the Real World Anhong Guo1, Xiang ‘Anthony’ Chen1, Haoran Qi2, Samuel White1, Suman Ghosh1, Chieko Asakawa3, Jeffrey P. Bigham1 1Human-Computer Interaction Institute, 2Mechanical Engineering Department, 3Robotics Institute Carnegie Mellon University, 5000 Forbes Ave, Pittsburgh, PA 15213 fanhongg, xiangche, chiekoa, jbighamg @cs.cmu.edu, fhaoranq, samw, sumangg @andrew.cmu.edu ABSTRACT INTRODUCTION The world is full of physical interfaces that are inaccessible The world is full of inaccessible physical interfaces. Mi to blind people, from microwaves and information kiosks to crowaves, toasters and coffee machines help us prepare food; thermostats and checkout terminals. Blind people cannot in printers, fax machines, and copiers help us work; and check dependently use such devices without at least first learning out terminals, public kiosks, and remote controls help us live their layout, and usually only after labeling them with sighted our lives. Despite their importance, few are self-voicing or assistance. We introduce VizLens —an accessible mobile ap have tactile labels. As a result, blind people cannot easily use plication and supporting backend that can robustly and inter them. Generally, blind people rely on sighted assistance ei actively help blind people use nearly any interface they en ther to use the interface or to label it with tactile markings. counter. VizLens users capture a photo of an inaccessible Tactile markings often cannot be added to interfaces on pub interface and send it to multiple crowd workers, who work lic devices, such as those in an office kitchenette or check in parallel to quickly label and describe elements of the inter out kiosk at the grocery store, and static labels cannot make face to make subsequent computer vision easier. -

VERSE: Bridging Screen Readers and Voice Assistants for Enhanced

VERSE: Bridging Screen Readers and Voice Assistants for Enhanced Eyes-Free Web Search Alexandra Vtyurina∗ Adam Fourney Meredith Ringel Morris University of Waterloo Microsoft Research Microsoft Research Waterloo, Ontario, Canada Redmond, WA, USA Redmond, WA, USA [email protected] [email protected] [email protected] Leah Findlater Ryen W. White University of Washington Microsoft Research Seattle, WA, USA Redmond, WA, USA [email protected] [email protected] ABSTRACT INTRODUCTION People with visual impairments often rely on screen readers People with visual impairments are often early adopters of when interacting with computer systems. Increasingly, these audio-based interfaces, with screen readers being a prime individuals also make extensive use of voice-based virtual example. Screen readers work by transforming the visual assistants (VAs). We conducted a survey of 53 people who are content in a graphical user interface into audio by vocalizing legally blind to identify the strengths and weaknesses of both on-screen text. To this end, they are an important accessibility technologies, and the unmet opportunities at their intersection. tool for blind computer users – so much so that every major We learned that virtual assistants are convenient and accessible, operating system includes screen reader functionality (e.g., but lack the ability to deeply engage with content (e.g., read VoiceOver1, TalkBack2, Narrator3), and there is a strong mar- beyond the frst few sentences of an article), and the ability ket for third-party offerings (e.g., JAWS4, NVDA5). Despite to get a quick overview of the landscape (e.g., list alternative their importance, screen readers have many limitations. -

Turning Voiceover on with Siri 1

Texas School for the Blind and Visually Impaired Outreach Programs www.tsbvi.edu | 512.454.8631 | 1100 W. 45th St. | Austin, TX 78756 Coffee Hour - August 27, 2020 VoiceOver Basics on iOS Presented by Carrie Farraje Introduction: Question: What is VoiceOver? Answer: VoiceOver is a screen reader software that is built into iOS devices such as iPads or iPhones that gives audio description of the screen that people with vision navigate with their eyes. Note: There are multiple ways and gestures to access an iOS device with VoiceOver Important Terms • iOS device: iPad, iPhone, Apple Watch • home button: newer devices do not have a Home button • settings: location of iOS setup and customization • orientation: landscape or portrait • app: application • app icons: small picture that represents an app • page: apps are in rows and columns on a page • gestures: touches that create actions • focus: what has the attention of VoiceOver • page adjuster: to navigate to different pages • dock: area on bottom of screen customized with commonly used apps • status bar: where features such as time, date, battery are located • control center: direct access to customizable settings 1 Turning VoiceOver on in Settings 1. Go to the Settings icon 2. Go to General 3. Go to Accessibility 4. Go to VoiceOver and, tap it on 5. Press Home button to go back to the home screen Turning VoiceOver on with Accessibility Shortcut 1. Go to the Settings icon 2. Go to Accessibility 3. Go to Accessibility Shortcut (at the bottom of the screen) 4. Tap VoiceOver on 5. Turn VoiceOver on by pressing the Home button or the top side button(on newer devices) three times. -

Slide Rule: Making Mobile Touch Screens Accessible to Blind People Using Multi-Touch Interaction Techniques Shaun K

Slide Rule: Making Mobile Touch Screens Accessible to Blind People Using Multi-Touch Interaction Techniques Shaun K. Kane,1 Jeffrey P. Bigham2 and Jacob O. Wobbrock1 1 2 The Information School Computer Science & Engineering DUB Group DUB Group University of Washington University of Washington Seattle, WA 98195 USA Seattle, WA 98195 USA {skane, wobbrock}@u.washington.edu [email protected] ABSTRACT Recent advances in touch screen technology have increased the prevalence of touch screens and have prompted a wave of new touch screen-based devices. However, touch screens are still largely inaccessible to blind users, who must adopt error-prone compensatory strategies to use them or find accessible alternatives. This inaccessibility is due to interaction techniques that require the user to visually locate objects on the screen. To address this problem, we introduce Slide Rule, a set of audio- based multi-touch interaction techniques that enable blind users to access touch screen applications. We describe the design of Slide Rule, our interaction techniques, and a user study in which 10 blind people used Slide Rule and a button-based Pocket PC screen reader. Results show that Slide Rule was significantly faster than Figure 1. Participant using Slide Rule on a multi-touch the button-based system, and was preferred by 7 of 10 users. smartphone. Slide Rule uses audio output only and does not However, users made more errors when using Slide Rule than display information on the screen. when using the more familiar button-based system. different interfaces on the same surface, such as a scrollable list, a Categories and Subject Descriptors: QWERTY keyboard, or a telephone keypad. -

Darkreader: Bridging the Gap Between Perception and Reality Of

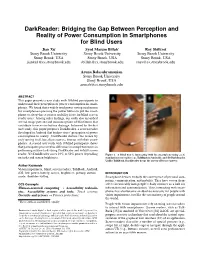

DarkReader: Bridging the Gap Between Perception and Reality of Power Consumption in Smartphones for Blind Users Jian Xu∗ Syed Masum Billah* Roy Shilkrot Stony Brook University Stony Brook University Stony Brook University Stony Brook, USA Stony Brook, USA Stony Brook, USA [email protected] [email protected] [email protected] Aruna Balasubramanian Stony Brook University Stony Brook, USA [email protected] ABSTRACT This paper presents a user study with 10 blind participants to understand their perception of power consumption in smart- phones. We found that a widely used power saving mechanism for smartphones–pressing the power button to put the smart- phone to sleep–has a serious usability issue for blind screen reader users. Among other findings, our study also unearthed several usage patterns and misconceptions of blind users that contribute to excessive battery drainage. Informed by the first user study, this paper proposes DarkReader, a screen reader developed in Android that bridges users’ perception of power consumption to reality. DarkReader darkens the screen by truly turning it off, but allows users to interact with their smart- phones. A second user study with 10 blind participants shows that participants perceived no difference in completion times in performing routine tasks using DarkReader and default screen reader. Yet DarkReader saves 24% to 52% power depending Figure 1. A blind user is interacting with his smartphone using a (A) on tasks and screen brightness. standard screen reader (e.g., TalkBack in Android), and (B) DarkReader. Unlike TalkBack, DarkReader keeps the screen off to save power. Author Keywords Vision impairment, blind; screen readers, TalkBack, Android, iOS; low-power, battery, screen, brightness; privacy, curtain INTRODUCTION mode, shoulder-surfing. -

Creating Word Documents Which Are Accessible for Screen Readers

Creating Word Documents which are Accessible for Screen Readers Create Properly Formatted Titles and Paragraph Headings It is important to create uniform headings in your document so that a screen reader can navigate the document and the reader can understand how the document is structured. When you create a heading in a document, such as a title or a paragraph heading, it is not enough simply to bold the text or increase the font size. A screen reader cannot “see” the bold letters. Always use the “Style” tool in Microsoft Word. The Style tool enables you to create consistent headings so that an individual can follow how your document is organized. Instructions for Word 2007 and above on PCs • Select your heading text. • Using the Style tool at the top of the menu bar, click on the appropriate style (e.g., Heading 1, Heading 2, etc.). The document title should be marked as Heading 1. Major topic headings should be Heading 2. Subtopic headings should be Heading 3. Sub-subtopics should be Heading 4, and so on. Do not skip heading levels. Instructions for Macs • The Style menu can be found in the Formatting palette. Create Properly Formatted Lists • If you need to create a list in a document, use the appropriate button (e.g., bullets and numbering) on Word’s formatting toolbar. Avoid making lists with just dashes or asterisks; otherwise a screen reader may not be able to read the list in the proper order. A properly formatted list would look like the ones below: • Apples • Bananas • Oranges Or 1. -

Community Notebook

Community Notebook Free Software Projects Projects on the Move Accessibility for computer users with disabilities is one of the noblest goals for Linux and open source software. Vinux, Orca, and Gnome lead the way in Linux accessibility. By Carla Schroder ccessibility of any kind for people with disabilities has a long history of neglect and opposition. The US Rehabilitation Act of 1973 prohibited fed- eral agencies from discriminating on the basis of disability (Sections 501, A503, 504, 508) [1]. Passing a law is one thing; enforcing it is another, and it took years of activism to make any progress. In the 1980s, the Reagan Adminis- tration targeted Section 504 (addressing civil rights for people with disabilities) for de- Lisa Young, 123RF regulation because it was too “burdensome.” Once again advocates organized, and after two years of intensive effort, they succeeded in preserving Section 504. However, years more of Supreme Court fights, legislative battles, and public education efforts had to be won. The culmination of that work was the Americans with Disabilities Act (ADA) of 1990, which addresses some of the basic aspects of everyday life: employ- ment, public accommodations, telecommunications, and government agencies. This law still leaves an awful lot of gaps. Designing for accessibility is more than just bolting on a few aids as an afterthought – it’s a matter of architecture, of design- ing for everyone from the ground up. Accessibility covers a lot of ground, including: • Impaired vision to complete blindness • Impaired hearing to complete deafness • Color blindness • Difficulty or inability to type or use a mouse • Cognitive, learning, or reading problems • Low stamina, difficulty sitting up Talking computers have existed in science fiction for decades, but the world isn’t much closer to having them than it was 10 years ago. -

Exploring User Interface Improvements for Software Developers Who Are Blind

Exploring User Interface Improvements for Software Developers who are Blind Guarionex Salivia* Flint Million Minnesota State University-Mankato Minnesota State University-Mankato Megan Bening Minnesota State University-Mankato Abstract: Software developers who are blind and interact with the computer non-visually face unique challenges with information retrieval. We explore the use of speech and Braille combined with software to provide an improved interface to aid with challenges associated with information retrieval. We motivate our design on common tasks performed by students in a software development course using a Microprocessor without Interlocked Pipeline Stages (MIPS) architecture simulation tool. We test our interface via a single-subject longitudinal study, and we measure and show improvement in both the user’s performance and the user experience. Keywords: Accessibility; Blindness; Visual Impairments; Braille; Screen reader technology; Software development *Corresponding Author, Guarionex Salivia [email protected] Submitted October, 2019 Accepted February 4, 2020 Published online July 23, 2020 1 Vol. 23, No. 1 - 2020; Journal of Science Education for Students with Disabilities 1. INTRODUCTION problem, because these interfaces provide information contextually via visual cues, People who are blind face unique challenges as which are clearly not specifically designed for software developers. Screen reading individuals who are blind and may not work technology is often unable to adequately with existing accessibility tools such as screen represent the complex and dynamic nature of readers. Therefore, those who are blind or modern application interfaces often used for visually impaired often find IDEs to be software development. Complex interfaces challenging to work with, and in many make the task of information seeking and situations completely unusable even with the retrieval particularly challenging to developers use of screen reading technology (Lazar, Allen, who are blind. -

In Proceedings of ACM Sympo- Sium on User Interface Software and Technology, UIST’92, November 1992

[Bur92b] David Burgess. "Low Cost Sound Spatialization." In Proceedings of ACM Sympo- sium on User Interface Software and Technology, UIST’92, November 1992. [Bux86] William Buxton."Human Interface Design and the Handicapped User." In Pro- ceedings of ACM Conference on Computer-Human Interaction, CHI’86, pp. 291- 297, 1986. [Edwa89] Alistair D. N. Edwards. “Modeling Blind User’s Interactions with an Auditory Computer Interface.” International Journal of Man-Machine Studies, pp 575-589, 1989. [Gav89] William W. Gaver. “The Sonicfinder: An Interface that uses Auditory Icons.” Human Computer Interaction, 4:67-94, 1989. [HTAP90] HumanWare, Artic Technologies, ADHOC, and The Reader Project. “Making Good Decisions on Technology: Access Solutions for Blindness and Low Vision.” In Closing the Gap Conference, October 1990. Industry Experts Panel Discussion. [Lad88] Richard E. Ladner. Public law 99-506, section 508, Electronic Equipment Accessi- bility for Disabled Workers. In Proceedings of ACM Conference on Computer- Human Interaction, CHI’88, pp. 219-222, 1988. [LC91] Lester F. Ludwig and Michael Cohen. “Multidimensional Audio Window Manage- ment.” International Journal of Man-Machine Studies, 34:3, pp. 319-336, March 1991. [LPC90] Lester F. Ludwig, Natalio Pincever, and Michael Cohen. “Extending the Notion of a Window System to Audio.” Computer, pp. 66-72, August 1990. [ME92a] Elizabeth Mynatt and W. Keith Edwards. "The Mercator Environment: A Nonvi- sual Interface to X Windows and Unix Workstations." GVU Technical Report GIT- GVU-92-05. February 1992. [ME92b] Elizabeth Mynatt and W. Keith Edwards. "Mapping GUIs to Auditory Interfaces." In Proceedings of ACM Symposium on User Interface Software and Technology, UIST’92, 1992.