Effect of Fructans, Prebiotics and Fibres on the Human Gut Microbiome Assessed by 16S Rrna-Based Approaches: a Review

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Influence of Probiotics on the Firmicutes/Bacteroidetes Ratio In

microorganisms Review The Influence of Probiotics on the Firmicutes/Bacteroidetes Ratio in the Treatment of Obesity and Inflammatory Bowel disease Spase Stojanov 1,2, Aleš Berlec 1,2 and Borut Štrukelj 1,2,* 1 Faculty of Pharmacy, University of Ljubljana, SI-1000 Ljubljana, Slovenia; [email protected] (S.S.); [email protected] (A.B.) 2 Department of Biotechnology, Jožef Stefan Institute, SI-1000 Ljubljana, Slovenia * Correspondence: borut.strukelj@ffa.uni-lj.si Received: 16 September 2020; Accepted: 31 October 2020; Published: 1 November 2020 Abstract: The two most important bacterial phyla in the gastrointestinal tract, Firmicutes and Bacteroidetes, have gained much attention in recent years. The Firmicutes/Bacteroidetes (F/B) ratio is widely accepted to have an important influence in maintaining normal intestinal homeostasis. Increased or decreased F/B ratio is regarded as dysbiosis, whereby the former is usually observed with obesity, and the latter with inflammatory bowel disease (IBD). Probiotics as live microorganisms can confer health benefits to the host when administered in adequate amounts. There is considerable evidence of their nutritional and immunosuppressive properties including reports that elucidate the association of probiotics with the F/B ratio, obesity, and IBD. Orally administered probiotics can contribute to the restoration of dysbiotic microbiota and to the prevention of obesity or IBD. However, as the effects of different probiotics on the F/B ratio differ, selecting the appropriate species or mixture is crucial. The most commonly tested probiotics for modifying the F/B ratio and treating obesity and IBD are from the genus Lactobacillus. In this paper, we review the effects of probiotics on the F/B ratio that lead to weight loss or immunosuppression. -

The 2014 Golden Gate National Parks Bioblitz - Data Management and the Event Species List Achieving a Quality Dataset from a Large Scale Event

National Park Service U.S. Department of the Interior Natural Resource Stewardship and Science The 2014 Golden Gate National Parks BioBlitz - Data Management and the Event Species List Achieving a Quality Dataset from a Large Scale Event Natural Resource Report NPS/GOGA/NRR—2016/1147 ON THIS PAGE Photograph of BioBlitz participants conducting data entry into iNaturalist. Photograph courtesy of the National Park Service. ON THE COVER Photograph of BioBlitz participants collecting aquatic species data in the Presidio of San Francisco. Photograph courtesy of National Park Service. The 2014 Golden Gate National Parks BioBlitz - Data Management and the Event Species List Achieving a Quality Dataset from a Large Scale Event Natural Resource Report NPS/GOGA/NRR—2016/1147 Elizabeth Edson1, Michelle O’Herron1, Alison Forrestel2, Daniel George3 1Golden Gate Parks Conservancy Building 201 Fort Mason San Francisco, CA 94129 2National Park Service. Golden Gate National Recreation Area Fort Cronkhite, Bldg. 1061 Sausalito, CA 94965 3National Park Service. San Francisco Bay Area Network Inventory & Monitoring Program Manager Fort Cronkhite, Bldg. 1063 Sausalito, CA 94965 March 2016 U.S. Department of the Interior National Park Service Natural Resource Stewardship and Science Fort Collins, Colorado The National Park Service, Natural Resource Stewardship and Science office in Fort Collins, Colorado, publishes a range of reports that address natural resource topics. These reports are of interest and applicability to a broad audience in the National Park Service and others in natural resource management, including scientists, conservation and environmental constituencies, and the public. The Natural Resource Report Series is used to disseminate comprehensive information and analysis about natural resources and related topics concerning lands managed by the National Park Service. -

Evaluation of 16S Rrna Primer Sets for Characterisation of Microbiota in Paediatric Patients with Autism Spectrum Disorder L

www.nature.com/scientificreports OPEN Evaluation of 16S rRNA primer sets for characterisation of microbiota in paediatric patients with autism spectrum disorder L. Palkova1,2, A. Tomova3, G. Repiska3, K. Babinska3, B. Bokor4, I. Mikula5, G. Minarik2, D. Ostatnikova3 & K. Soltys4,6* Abstract intestinal microbiota is becoming a signifcant marker that refects diferences between health and disease status also in terms of gut-brain axis communication. Studies show that children with autism spectrum disorder (ASD) often have a mix of gut microbes that is distinct from the neurotypical children. Various assays are being used for microbiota investigation and were considered to be universal. However, newer studies showed that protocol for preparing DNA sequencing libraries is a key factor infuencing results of microbiota investigation. The choice of DNA amplifcation primers seems to be the crucial for the outcome of analysis. In our study, we have tested 3 primer sets to investigate diferences in outcome of sequencing analysis of microbiota in children with ASD. We found out that primers detected diferent portion of bacteria in samples especially at phylum level; signifcantly higher abundance of Bacteroides and lower Firmicutes were detected using 515f/806r compared to 27f/1492r and 27f*/1495f primers. So, the question is whether a gold standard of Firmicutes/Bacteroidetes ratio is a valuable and reliable universal marker, since two primer sets towards 16S rRNA can provide opposite information. Moreover, signifcantly higher relative abundance of Proteobacteria was detected using 27f/1492r. The beta diversity of sample groups difered remarkably and so the number of observed bacterial genera. An advent of massively parallel sequencing (MPS) technologies has revolutionized an investigating of human microbiota1. -

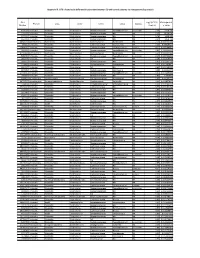

Appendix III: OTU's Found to Be Differentially Abundant Between CD and Control Patients Via Metagenomeseq Analysis

Appendix III: OTU's found to be differentially abundant between CD and control patients via metagenomeSeq analysis OTU Log2 (FC CD / FDR Adjusted Phylum Class Order Family Genus Species Number Control) p value 518372 Firmicutes Clostridia Clostridiales Ruminococcaceae Faecalibacterium prausnitzii 2.16 5.69E-08 194497 Firmicutes Clostridia Clostridiales Ruminococcaceae NA NA 2.15 8.93E-06 175761 Firmicutes Clostridia Clostridiales Ruminococcaceae NA NA 5.74 1.99E-05 193709 Firmicutes Clostridia Clostridiales Ruminococcaceae NA NA 2.40 2.14E-05 4464079 Bacteroidetes Bacteroidia Bacteroidales Bacteroidaceae Bacteroides NA 7.79 0.000123188 20421 Firmicutes Clostridia Clostridiales Lachnospiraceae Coprococcus NA 1.19 0.00013719 3044876 Firmicutes Clostridia Clostridiales Lachnospiraceae [Ruminococcus] gnavus -4.32 0.000194983 184000 Firmicutes Clostridia Clostridiales Ruminococcaceae Faecalibacterium prausnitzii 2.81 0.000306032 4392484 Bacteroidetes Bacteroidia Bacteroidales Bacteroidaceae Bacteroides NA 5.53 0.000339948 528715 Firmicutes Clostridia Clostridiales Ruminococcaceae Faecalibacterium prausnitzii 2.17 0.000722263 186707 Firmicutes Clostridia Clostridiales NA NA NA 2.28 0.001028539 193101 Firmicutes Clostridia Clostridiales Ruminococcaceae NA NA 1.90 0.001230738 339685 Firmicutes Clostridia Clostridiales Peptococcaceae Peptococcus NA 3.52 0.001382447 101237 Firmicutes Clostridia Clostridiales NA NA NA 2.64 0.001415109 347690 Firmicutes Clostridia Clostridiales Ruminococcaceae Oscillospira NA 3.18 0.00152075 2110315 Firmicutes Clostridia -

Recruitment of Reverse Transcriptase-Cas1 Fusion Proteins by Type VI-A CRISPR-Cas Systems

fmicb-10-02160 September 12, 2019 Time: 16:22 # 1 ORIGINAL RESEARCH published: 13 September 2019 doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2019.02160 Recruitment of Reverse Transcriptase-Cas1 Fusion Proteins by Type VI-A CRISPR-Cas Systems Nicolás Toro*, Mario Rodríguez Mestre, Francisco Martínez-Abarca and Alejandro González-Delgado Structure, Dynamics and Function of Rhizobacterial Genomes, Department of Soil Microbiology and Symbiotic Systems, Estación Experimental del Zaidín, Consejo Superior de Investigaciones Científicas, Granada, Spain Type VI CRISPR–Cas systems contain a single effector nuclease (Cas13) that exclusively targets single-stranded RNA. It remains unknown how these systems acquire spacers. It has been suggested that type VI systems with adaptation modules can acquire spacers from RNA bacteriophages, but sequence similarities suggest that spacers may provide Edited by: Kira Makarova, immunity to DNA phages. We searched databases for Cas13 proteins with linked RTs. National Center for Biotechnology We identified two different type VI-A systems with adaptation modules including an Information (NLM), United States RT-Cas1 fusion and Cas2 proteins. Phylogenetic reconstruction analyses revealed that Reviewed by: these adaptation modules were recruited by different effector Cas13a proteins, possibly Yuri Wolf, National Center for Biotechnology from RT-associated type III-D systems within the bacterial classes Alphaproteobacteria Information (NLM), United States and Clostridia. These type VI-A systems are predicted to acquire spacers from RNA Omar -

Development of the Equine Hindgut Microbiome in Semi-Feral and Domestic Conventionally-Managed Foals Meredith K

Tavenner et al. Animal Microbiome (2020) 2:43 Animal Microbiome https://doi.org/10.1186/s42523-020-00060-6 RESEARCH ARTICLE Open Access Development of the equine hindgut microbiome in semi-feral and domestic conventionally-managed foals Meredith K. Tavenner1, Sue M. McDonnell2 and Amy S. Biddle1* Abstract Background: Early development of the gut microbiome is an essential part of neonate health in animals. It is unclear whether the acquisition of gut microbes is different between domesticated animals and their wild counterparts. In this study, fecal samples from ten domestic conventionally managed (DCM) Standardbred and ten semi-feral managed (SFM) Shetland-type pony foals and dams were compared using 16S rRNA sequencing to identify differences in the development of the foal hindgut microbiome related to time and management. Results: Gut microbiome diversity of dams was lower than foals overall and within groups, and foals from both groups at Week 1 had less diverse gut microbiomes than subsequent weeks. The core microbiomes of SFM dams and foals had more taxa overall, and greater numbers of taxa within species groups when compared to DCM dams and foals. The gut microbiomes of SFM foals demonstrated enhanced diversity of key groups: Verrucomicrobia (RFP12), Ruminococcaceae, Fusobacterium spp., and Bacteroides spp., based on age and management. Lactic acid bacteria Lactobacillus spp. and other Lactobacillaceae genera were enriched only in DCM foals, specifically during their second and third week of life. Predicted microbiome functions estimated computationally suggested that SFM foals had higher mean sequence counts for taxa contributing to the digestion of lipids, simple and complex carbohydrates, and protein. -

WO 2018/064165 A2 (.Pdf)

(12) INTERNATIONAL APPLICATION PUBLISHED UNDER THE PATENT COOPERATION TREATY (PCT) (19) World Intellectual Property Organization International Bureau (10) International Publication Number (43) International Publication Date WO 2018/064165 A2 05 April 2018 (05.04.2018) W !P O PCT (51) International Patent Classification: Published: A61K 35/74 (20 15.0 1) C12N 1/21 (2006 .01) — without international search report and to be republished (21) International Application Number: upon receipt of that report (Rule 48.2(g)) PCT/US2017/053717 — with sequence listing part of description (Rule 5.2(a)) (22) International Filing Date: 27 September 2017 (27.09.2017) (25) Filing Language: English (26) Publication Langi English (30) Priority Data: 62/400,372 27 September 2016 (27.09.2016) US 62/508,885 19 May 2017 (19.05.2017) US 62/557,566 12 September 2017 (12.09.2017) US (71) Applicant: BOARD OF REGENTS, THE UNIVERSI¬ TY OF TEXAS SYSTEM [US/US]; 210 West 7th St., Austin, TX 78701 (US). (72) Inventors: WARGO, Jennifer; 1814 Bissonnet St., Hous ton, TX 77005 (US). GOPALAKRISHNAN, Vanch- eswaran; 7900 Cambridge, Apt. 10-lb, Houston, TX 77054 (US). (74) Agent: BYRD, Marshall, P.; Parker Highlander PLLC, 1120 S. Capital Of Texas Highway, Bldg. One, Suite 200, Austin, TX 78746 (US). (81) Designated States (unless otherwise indicated, for every kind of national protection available): AE, AG, AL, AM, AO, AT, AU, AZ, BA, BB, BG, BH, BN, BR, BW, BY, BZ, CA, CH, CL, CN, CO, CR, CU, CZ, DE, DJ, DK, DM, DO, DZ, EC, EE, EG, ES, FI, GB, GD, GE, GH, GM, GT, HN, HR, HU, ID, IL, IN, IR, IS, JO, JP, KE, KG, KH, KN, KP, KR, KW, KZ, LA, LC, LK, LR, LS, LU, LY, MA, MD, ME, MG, MK, MN, MW, MX, MY, MZ, NA, NG, NI, NO, NZ, OM, PA, PE, PG, PH, PL, PT, QA, RO, RS, RU, RW, SA, SC, SD, SE, SG, SK, SL, SM, ST, SV, SY, TH, TJ, TM, TN, TR, TT, TZ, UA, UG, US, UZ, VC, VN, ZA, ZM, ZW. -

Characterization of an Adapted Microbial Population to the Bioconversion of Carbon Monoxide Into Butanol Using Next-Generation Sequencing Technology

Characterization of an adapted microbial population to the bioconversion of carbon monoxide into butanol using next-generation sequencing technology Guillaume Bruant Research officer, Bioengineering group Energy, Mining, Environment - National Research Council Canada Pacific Rim Summit on Industrial Biotechnology and Bioenergy December 8 -11, 2013 Butanol from residue (dry): syngas route biomass → gasification → syngas → catalysis → synfuels (CO, H2, CO2, CH4) (alcohols…) Biocatalysis vs Chemical catalysis potential for higher product specificity may be less problematic when impurities present less energy intensive (low pressure and temperature) Anaerobic undefined mixed culture vs bacterial pure culture mesophilic anaerobic sludge treating agricultural wastes (Lassonde Inc, Rougemont, QC, Canada) PRS 2013 - 2 Experimental design CO Alcohols Serum bottles incubated at Next Generation RDP Pyrosequencing mesophilic temperature Sequencing (NGS) pipeline 35°C for 2 months Ion PGMTM sequencer http://pyro.cme.msu.edu/ sequences filtered CO continuously supplied Monitoring of bacterial and to the gas phase archaeal populations RDP classifier atmosphere of 100% CO, http://rdp.cme.msu.edu/ 1 atm 16S rRNA genes Ion 314TM chip classifier VFAs & alcohol production bootstrap confidence cutoff low level of butanol of 50 % Samples taken after 1 and 2 months total genomic DNA extracted, purified, concentrated PRS 2013 - 3 NGS: bacterial results Bacterial population - Phylum level 100% 80% Other Chloroflexi 60% Synergistetes % -

Analyse Bibliographique Sur Le Microbiote Intestinal Et Son Etude Dans Des Modeles Animaux De Maladies Metaboliques, En Particulier Chez Le Primate Non Humain These

VETAGRO SUP CAMPUS VETERINAIRE DE LYON Année 2019 - Thèse n°111 ANALYSE BIBLIOGRAPHIQUE SUR LE MICROBIOTE INTESTINAL ET SON ETUDE DANS DES MODELES ANIMAUX DE MALADIES METABOLIQUES, EN PARTICULIER CHEZ LE PRIMATE NON HUMAIN THESE Présentée à l’UNIVERSITE CLAUDE-BERNARD - LYON I (Médecine - Pharmacie) et soutenue publiquement le 6 décembre 2019 pour obtenir le grade de Docteur Vétérinaire par SCHUTZ Charlotte Née le 5 mars 1994 à Zürich (Suisse) VETAGRO SUP CAMPUS VETERINAIRE DE LYON Année 2019 - Thèse n°111 ANALYSE BIBLIOGRAPHIQUE SUR LE MICROBIOTE INTESTINAL ET SON ETUDE DANS DES MODELES ANIMAUX DE MALADIES METABOLIQUES, EN PARTICULIER CHEZ LE PRIMATE NON HUMAIN THESE Présentée à l’UNIVERSITE CLAUDE-BERNARD - LYON I (Médecine - Pharmacie) et soutenue publiquement le 6 décembre 2019 pour obtenir le grade de Docteur Vétérinaire par SCHUTZ Charlotte Née le 5 mars 1994 à Zürich (Suisse) Liste du corps enseignant Liste des Enseignants du Campus Vétérinaire de Lyon (01-09-2019) ABITBOL Marie DEPT-BASIC-SCIENCES Professeur ALVES-DE-OLIVEIRA Laurent DEPT-BASIC-SCIENCES Maître de conférences ARCANGIOLI Marie-Anne DEPT-ELEVAGE-SPV Professeur AYRAL Florence DEPT-ELEVAGE-SPV Maître de conférences BECKER Claire DEPT-ELEVAGE-SPV Maître de conférences BELLUCO Sara DEPT-AC-LOISIR-SPORT Maître de conférences BENAMOU-SMITH Agnès DEPT-AC-LOISIR-SPORT Maître de conférences BENOIT Etienne DEPT-BASIC-SCIENCES Professeur BERNY Philippe DEPT-BASIC-SCIENCES Professeur BONNET-GARIN Jeanne-Marie DEPT-BASIC-SCIENCES Professeur BOULOCHER Caroline DEPT-BASIC-SCIENCES -

The Isolation of Novel Lachnospiraceae Strains and the Evaluation of Their Potential Roles in Colonization Resistance Against Clostridium Difficile

The isolation of novel Lachnospiraceae strains and the evaluation of their potential roles in colonization resistance against Clostridium difficile Diane Yuan Wang Honors Thesis in Biology Department of Ecology and Evolutionary Biology College of Literature, Science, & the Arts University of Michigan, Ann Arbor April 1st, 2014 Sponsor: Vincent B. Young, M.D., Ph.D. Associate Professor of Internal Medicine Associate Professor of Microbiology and Immunology Medical School Co-Sponsor: Aaron A. King, Ph.D. Associate Professor of Ecology & Evolutionary Associate Professor of Mathematics College of Literature, Science, & the Arts Reader: Blaise R. Boles, Ph.D. Assistant Professor of Molecular, Cellular and Developmental Biology College of Literature, Science, & the Arts 1 Table of Contents Abstract 3 Introduction 4 Clostridium difficile 4 Colonization Resistance 5 Lachnospiraceae 6 Objectives 7 Materials & Methods 9 Sample Collection 9 Bacterial Isolation and Selective Growth Conditions 9 Design of Lachnospiraceae 16S rRNA-encoding gene primers 9 DNA extraction and 16S ribosomal rRNA-encoding gene sequencing 10 Phylogenetic analyses 11 Direct inhibition 11 Bile salt hydrolase (BSH) detection 12 PCR assay for bile acid 7α-dehydroxylase detection 12 Tables & Figures Table 1 13 Table 2 15 Table 3 21 Table 4 25 Figure 1 16 Figure 2 19 Figure 3 20 Figure 4 24 Figure 5 26 Results 14 Isolation of novel Lachnospiraceae strains 14 Direct inhibition 17 Bile acid physiology 22 Discussion 27 Acknowledgments 33 References 34 2 Abstract Background: Antibiotic disruption of the gastrointestinal tract’s indigenous microbiota can lead to one of the most common nosocomial infections, Clostridium difficile, which has an annual cost exceeding $4.8 billion dollars. -

Breast Milk Microbiota: a Review of the Factors That Influence Composition

Published in "Journal of Infection 81(1): 17–47, 2020" which should be cited to refer to this work. ✩ Breast milk microbiota: A review of the factors that influence composition ∗ Petra Zimmermann a,b,c,d, , Nigel Curtis b,c,d a Department of Paediatrics, Fribourg Hospital HFR and Faculty of Science and Medicine, University of Fribourg, Switzerland b Department of Paediatrics, The University of Melbourne, Parkville, Australia c Infectious Diseases Research Group, Murdoch Children’s Research Institute, Parkville, Australia d Infectious Diseases Unit, The Royal Children’s Hospital Melbourne, Parkville, Australia s u m m a r y Breastfeeding is associated with considerable health benefits for infants. Aside from essential nutrients, immune cells and bioactive components, breast milk also contains a diverse range of microbes, which are important for maintaining mammary and infant health. In this review, we summarise studies that have Keywords: investigated the composition of the breast milk microbiota and factors that might influence it. Microbiome We identified 44 studies investigating 3105 breast milk samples from 2655 women. Several studies Diversity reported that the bacterial diversity is higher in breast milk than infant or maternal faeces. The maxi- Delivery mum number of each bacterial taxonomic level detected per study was 58 phyla, 133 classes, 263 orders, Caesarean 596 families, 590 genera, 1300 species and 3563 operational taxonomic units. Furthermore, fungal, ar- GBS chaeal, eukaryotic and viral DNA was also detected. The most frequently found genera were Staphylococ- Antibiotics cus, Streptococcus Lactobacillus, Pseudomonas, Bifidobacterium, Corynebacterium, Enterococcus, Acinetobacter, BMI Rothia, Cutibacterium, Veillonella and Bacteroides. There was some evidence that gestational age, delivery Probiotics mode, biological sex, parity, intrapartum antibiotics, lactation stage, diet, BMI, composition of breast milk, Smoking Diet HIV infection, geographic location and collection/feeding method influence the composition of the breast milk microbiota. -

Gut Microbiota Differs in Composition and Functionality Between Children

Diabetes Care Volume 41, November 2018 2385 Gut Microbiota Differs in Isabel Leiva-Gea,1 Lidia Sanchez-Alcoholado,´ 2 Composition and Functionality Beatriz Mart´ın-Tejedor,1 Daniel Castellano-Castillo,2,3 Between Children With Type 1 Isabel Moreno-Indias,2,3 Antonio Urda-Cardona,1 Diabetes and MODY2 and Healthy Francisco J. Tinahones,2,3 Jose´ Carlos Fernandez-Garc´ ´ıa,2,3 and Control Subjects: A Case-Control Mar´ıa Isabel Queipo-Ortuno~ 2,3 Study Diabetes Care 2018;41:2385–2395 | https://doi.org/10.2337/dc18-0253 OBJECTIVE Type 1 diabetes is associated with compositional differences in gut microbiota. To date, no microbiome studies have been performed in maturity-onset diabetes of the young 2 (MODY2), a monogenic cause of diabetes. Gut microbiota of type 1 diabetes, MODY2, and healthy control subjects was compared. PATHOPHYSIOLOGY/COMPLICATIONS RESEARCH DESIGN AND METHODS This was a case-control study in 15 children with type 1 diabetes, 15 children with MODY2, and 13 healthy children. Metabolic control and potential factors mod- ifying gut microbiota were controlled. Microbiome composition was determined by 16S rRNA pyrosequencing. 1Pediatric Endocrinology, Hospital Materno- Infantil, Malaga,´ Spain RESULTS 2Clinical Management Unit of Endocrinology and Compared with healthy control subjects, type 1 diabetes was associated with a Nutrition, Laboratory of the Biomedical Research significantly lower microbiota diversity, a significantly higher relative abundance of Institute of Malaga,´ Virgen de la Victoria Uni- Bacteroides Ruminococcus Veillonella Blautia Streptococcus versityHospital,Universidad de Malaga,M´ alaga,´ , , , , and genera, and a Spain lower relative abundance of Bifidobacterium, Roseburia, Faecalibacterium, and 3Centro de Investigacion´ BiomedicaenRed(CIBER)´ Lachnospira.