Albert Einstein As the Father of Solid State Physics

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Einstein Solid 1 / 36 the Results 2

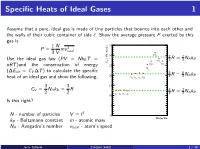

Specific Heats of Ideal Gases 1 Assume that a pure, ideal gas is made of tiny particles that bounce into each other and the walls of their cubic container of side `. Show the average pressure P exerted by this gas is 1 N 35 P = mv 2 3 V total SO 30 2 7 7 (J/K-mole) R = NAkB Use the ideal gas law (PV = NkB T = V 2 2 CO2 C H O CH nRT )and the conservation of energy 25 2 4 Cl2 (∆Eint = CV ∆T ) to calculate the specific 5 5 20 2 R = 2 NAkB heat of an ideal gas and show the following. H2 N2 O2 CO 3 3 15 CV = NAkB = R 3 3 R = NAkB 2 2 He Ar Ne Kr 2 2 10 Is this right? 5 3 N - number of particles V = ` 0 Molecule kB - Boltzmann constant m - atomic mass NA - Avogadro's number vtotal - atom's speed Jerry Gilfoyle Einstein Solid 1 / 36 The Results 2 1 N 2 2 N 7 P = mv = hEkini 2 NAkB 3 V total 3 V 35 30 SO2 3 (J/K-mole) V 5 CO2 C N k hEkini = NkB T H O CH 2 A B 2 25 2 4 Cl2 20 H N O CO 3 3 2 2 2 3 CV = NAkB = R 2 NAkB 2 2 15 He Ar Ne Kr 10 5 0 Molecule Jerry Gilfoyle Einstein Solid 2 / 36 Quantum mechanically 2 E qm = `(` + 1) ~ rot 2I where l is the angular momen- tum quantum number. -

Otto Sackur's Pioneering Exploits in the Quantum Theory Of

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Catalogo dei prodotti della ricerca Chapter 3 Putting the Quantum to Work: Otto Sackur’s Pioneering Exploits in the Quantum Theory of Gases Massimiliano Badino and Bretislav Friedrich After its appearance in the context of radiation theory, the quantum hypothesis rapidly diffused into other fields. By 1910, the crisis of classical traditions of physics and chemistry—while taking the quantum into account—became increas- ingly evident. The First Solvay Conference in 1911 pushed quantum theory to the fore, and many leading physicists responded by embracing the quantum hypoth- esis as a way to solve outstanding problems in the theory of matter. Until about 1910, quantum physics had drawn much of its inspiration from two sources. The first was the complex formal machinery connected with Max Planck’s theory of radiation and, above all, its close relationship with probabilis- tic arguments and statistical mechanics. The fledgling 1900–1901 version of this theory hinged on the application of Ludwig Boltzmann’s 1877 combinatorial pro- cedure to determine the state of maximum probability for a set of oscillators. In his 1906 book on heat radiation, Planck made the connection with gas theory even tighter. To illustrate the use of the procedure Boltzmann originally developed for an ideal gas, Planck showed how to extend the analysis of the phase space, com- monplace among practitioners of statistical mechanics, to electromagnetic oscil- lators (Planck 1906, 140–148). In doing so, Planck identified a crucial difference between the phase space of the gas molecules and that of oscillators used in quan- tum theory. -

Intermediate Statistics in Thermoelectric Properties of Solids

Intermediate statistics in thermoelectric properties of solids André A. Marinho1, Francisco A. Brito1,2 1 Departamento de Física, Universidade Federal de Campina Grande, 58109-970 Campina Grande, Paraíba, Brazil and 2 Departamento de Física, Universidade Federal da Paraíba, Caixa Postal 5008, 58051-970 João Pessoa, Paraíba, Brazil (Dated: July 23, 2019) Abstract We study the thermodynamics of a crystalline solid by applying intermediate statistics manifested by q-deformation. We based part of our study on both Einstein and Debye models, exploring primarily de- formed thermal and electrical conductivities as a function of the deformed Debye specific heat. The results revealed that the q-deformation acts in two different ways but not necessarily as independent mechanisms. It acts as a factor of disorder or impurity, modifying the characteristics of a crystalline structure, which are phenomena described by q-bosons, and also as a manifestation of intermediate statistics, the B-anyons (or B-type systems). For the latter case, we have identified the Schottky effect, normally associated with high-Tc superconductors in the presence of rare-earth-ion impurities, and also the increasing of the specific heat of the solids beyond the Dulong-Petit limit at high temperature, usually related to anharmonicity of interatomic interactions. Alternatively, since in the q-bosons the statistics are in principle maintained the effect of the deformation acts more slowly due to a small change in the crystal lattice. On the other hand, B-anyons that belong to modified statistics are more sensitive to the deformation. PACS numbers: 02.20-Uw, 05.30-d, 75.20-g arXiv:1907.09055v1 [cond-mat.stat-mech] 21 Jul 2019 1 I. -

Einstein's Physics

Einstein’s Physics Albert Einstein at Barnes Foundation in Merion PA, c.1947. Photography by Laura Delano Condax; gift to the author from Vanna Condax. Einstein’s Physics Atoms, Quanta, and Relativity Derived, Explained, and Appraised TA-PEI CHENG University of Missouri–St. Louis Portland State University 3 3 Great Clarendon Street, Oxford, OX2 6DP, United Kingdom Oxford University Press is a department of the University of Oxford. It furthers the University’s objective of excellence in research, scholarship, and education by publishing worldwide. Oxford is a registered trade mark of Oxford University Press in the UK and in certain other countries © Ta-Pei Cheng 2013 The moral rights of the author have been asserted Impression: 1 All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, without the prior permission in writing of Oxford University Press, or as expressly permitted by law, by licence or under terms agreed with the appropriate reprographics rights organization. Enquiries concerning reproduction outside the scope of the above should be sent to the Rights Department, Oxford University Press, at the address above You must not circulate this work in any other form and you must impose this same condition on any acquirer British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data Data available ISBN 978–0–19–966991–2 Printed and bound by CPI Group (UK) Ltd, Croydon, CR0 4YY Links to third party websites are provided by Oxford in good faith and for information only. Oxford disclaims any responsibility for the materials contained in any third party website referenced in this work. -

MOLAR HEAT of SOLIDS the Dulong–Petit Law, a Thermodynamic

MOLAR HEAT OF SOLIDS The Dulong–Petit law, a thermodynamic law proposed in 1819 by French physicists Dulong and Petit, states the classical expression for the molar specific heat of certain crystals. The two scientists conducted experiments on three dimensional solid crystals to determine the heat capacities of a variety of these solids. They discovered that all investigated solids had a heat capacity of approximately 25 J mol-1 K-1 room temperature. The result from their experiment was explained as follows. According to the Equipartition Theorem, each degree of freedom has an average energy of 1 = 2 where is the Boltzmann constant and is the absolute temperature. We can model the atoms of a solid as attached to neighboring atoms by springs. These springs extend into three-dimensional space. Each direction has 2 degrees of freedom: one kinetic and one potential. Thus every atom inside the solid was considered as a 3 dimensional oscillator with six degrees of freedom ( = 6) The more energy that is added to the solid the more these springs vibrate. Figure 1: Model of interaction of atoms of a solid Now the energy of each atom is = = 3 . The energy of N atoms is 6 = 3 2 = 3 where n is the number of moles. To change the temperature by ΔT via heating, one must transfer Q=3nRΔT to the crystal, thus the molar heat is JJ CR=3 ≈⋅ 3 8.31 ≈ 24.93 molK molK Similarly, the molar heat capacity of an atomic or molecular ideal gas is proportional to its number of degrees of freedom, : = 2 This explanation for Petit and Dulong's experiment was not sufficient when it was discovered that heat capacity decreased and going to zero as a function of T3 (or, for metals, T) as temperature approached absolute zero. -

First Principles Study of the Vibrational and Thermal Properties of Sn-Based Type II Clathrates, Csxsn136 (0 ≤ X ≤ 24) and Rb24ga24sn112

Article First Principles Study of the Vibrational and Thermal Properties of Sn-Based Type II Clathrates, CsxSn136 (0 ≤ x ≤ 24) and Rb24Ga24Sn112 Dong Xue * and Charles W. Myles Department of Physics and Astronomy, Texas Tech University, Lubbock, TX 79409-1051, USA; [email protected] * Correspondence: [email protected]; Tel.: +1-806-834-4563 Received: 12 May 2019; Accepted: 11 June 2019; Published: 14 June 2019 Abstract: After performing first-principles calculations of structural and vibrational properties of the semiconducting clathrates Rb24Ga24Sn112 along with binary CsxSn136 (0 ≤ x ≤ 24), we obtained equilibrium geometries and harmonic phonon modes. For the filled clathrate Rb24Ga24Sn112, the phonon dispersion relation predicts an upshift of the low-lying rattling modes (~25 cm−1) for the Rb (“rattler”) compared to Cs vibration in CsxSn136. It is also found that the large isotropic atomic displacement parameter (Uiso) exists when Rb occupies the “over-sized” cage (28 atom cage) rather than the 20 atom counterpart. These guest modes are expected to contribute significantly to minimizing the lattice’s thermal conductivity (κL). Our calculation of the vibrational contribution to the specific heat and our evaluation on κL are quantitatively presented and discussed. Specifically, the heat capacity diagram regarding CV/T3 vs. T exhibits the Einstein-peak-like hump that is mainly attributable to the guest oscillator in a 28 atom cage, with a characteristic temperature 36.82 K for Rb24Ga24Sn112. Our calculated rattling modes are around 25 cm−1 for the Rb trapped in a 28 atom cage, and 65.4 cm−1 for the Rb encapsulated in a 20 atom cage. -

Hostatmech.Pdf

A computational introduction to quantum statistics using harmonically trapped particles Martin Ligare∗ Department of Physics & Astronomy, Bucknell University, Lewisburg, PA 17837 (Dated: March 15, 2016) Abstract In a 1997 paper Moore and Schroeder argued that the development of student understanding of thermal physics could be enhanced by computational exercises that highlight the link between the statistical definition of entropy and the second law of thermodynamics [Am. J. Phys. 65, 26 (1997)]. I introduce examples of similar computational exercises for systems in which the quantum statistics of identical particles plays an important role. I treat isolated systems of small numbers of particles confined in a common harmonic potential, and use a computer to enumerate all possible occupation-number configurations and multiplicities. The examples illustrate the effect of quantum statistics on the sharing of energy between weakly interacting subsystems, as well as the distribution of energy within subsystems. The examples also highlight the onset of Bose-Einstein condensation in small systems. PACS numbers: 1 I. INTRODUCTION In a 1997 paper in this journal Moore and Schroeder argued that the development of student understanding of thermal physics could be enhanced by computational exercises that highlight the link between the statistical definition of entropy and the second law of thermodynamics.1 The first key to their approach was the use of a simple model, the Ein- stein solid, for which it is straightforward to develop an exact formula for the number of microstates of an isolated system. The second key was the use of a computer, rather than analytical approximations, to evaluate these formulas. -

Einstein Solids Interacting Solids Multiplicity of Solids PHYS 4311: Thermodynamics & Statistical Mechanics

Justin Einstein Solids Interacting Solids Multiplicity of Solids PHYS 4311: Thermodynamics & Statistical Mechanics Alejandro Garcia, Justin Gaumer, Chirag Gokani, Kristian Gonzalez, Nicholas Hamlin, Leonard Humphrey, Cullen Hutchison, Krishna Kalluri, Arjun Khurana Justin Introduction • Debye model(collective frequency motion) • Dulong–Petit law (behavior at high temperatures) predicted by Debye model •Polyatomic molecules 3R • dependence predicted by Debye model, too. • Einstein model not accurate at low temperatures Chirag Debye Model: Particle in a Box Chirag Quantum Harmonic Oscillator m<<1 S. eq. Chirag Discrete Evenly-Spaced Quanta of Energy Kristian What about in 3D? A single particle can "oscillate" each of the 3 cartesian directions: x, y, z. If we were just to look at a single atom subject to the harmonic oscillator potential in each cartesian direction, its total energy is the sum of energies corresponding to oscillations in the x direction, y direction, and z direction. Kristian Einstein Solid Model: Collection of Many Isotropic/Identical Harmonic Oscillators If our solid consists of N "oscillators" then there are N/3 atoms (each atom is subject to the harmonic oscillator potential in the 3 independent cartesian directions). Krishna What is the Multiplicity of an Einstein Solid with N oscillators? Our system has exactly N oscillators and q quanta of energy. This is the macrostate. There would be a certain number of microstates resulting from individual oscillators having different amounts of energy, but the whole solid having total q quanta of energy. Note that each microstate is equally probable! Krishna What is the Multiplicity of an Einstein Solid with N oscillators? Recall that energy comes in discrete quanta (units of hf) or "packets"! Each of the N oscillators will have an energy measure in integer units of hf! Question: Let an Einstein Solid of N oscillators have a fixed value of exactly q quanta of energy. -

'En Attendant Debye. L

Eur. J. F’hys. I(1980) 222-224. Rintcd in Northern Ireland 222 uniquecharacteristic frequency a+, failed to ac- count quantitatively for the observed behaviour; it predicted a temperature dependence of the specific heat ’En attendant I C, X@(+) Debye. l (where the ‘Einsteinfunction’ @(x) behaves like x’ e-x for x +m), leading to an exaggerated de- M Hulin crease of C, when T goes to zero, which does not correspond to the observed T3 behaviour.It was Equipe de Recherche sur la Diffusion et only with the Debye model (Debye 1912) that the 1’Enseignement de la Physique, Universite Pierre T3law was finally understood. et Marie Curie, Tour 32, 4 place Jussieu, 75231 This leaves one with a somewhat puzzling ques- Paris Cedex 05, France tion which we can put in the following way: why Received 9 December 1980 did Einstein not propose the ‘Debye model’? Ein- stein was of course quite familiar with the black body problem, and it is nowadays a very conven- Abstract The problem of the specific heat of solids and its behaviour at low temperatures played an impor- tional remark that a T3specific heat means a T4 tant role in the evolution of basic ideas in physics at the internal energy, that is, via Stefan’s law, a charac- turn of the century. It was finally solved by Debye, but teristic of the black body, which it is easy to trace why did Einstein, who showed a keen interest in that back to the linear dispersion law of electromagnetic problem for several years, fail to propose the Debye waves. -

Einstein Solid in a Few Minutes We Will See That We Can Use the Internal Energy U and the Number of Molecules, N to Define the State

Chapter 4 • We have spent some time developing the model of ideal gases and have learned a number of important concepts. However, we still have not learned much regarding why certain processes are irreversible. We are getting closer to that “holy grail”. But we need to define some more terms • In this chapter we go through all these points and by the end we will have all the pieces to understand why some processes are irreversible. • Macrostate: We defined this earlier for an ideal gas Most (not all) combinations of three of the following served to describe the macroscopic properties of an ideal gas: o U, T, P, V, N, M, along with the composition. For other things like liquid and solids we will have a similar set of variables that define the macroscopic state of the substance. When we define an Einstein Solid in a few minutes we will see that we can use the internal energy U and the number of molecules, N to define the state. 5/18/2004 H133 Spring 2004 1 Microstates • Microstate: The microstate of a system (gas, solid, or liquid) is defined as the set of quantities which defines the state of every molecule in the system. One option: We could also think about this as being the set of quantum numbers that describe each state of each particle. (This is what we will do for the Einstein Solid.) A quantum in a 1-d box If we extend this idea to 3-dimensions, Note that for N molecules we need In practice, it is impossible to determine the microstate of an object. -

Albert Einstein - Wikipedia, the Free Encyclopedia Page 1 of 27

Albert Einstein - Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia Page 1 of 27 Albert Einstein From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia Albert Einstein ( /ælbərt a nsta n/; Albert Einstein German: [albt a nʃta n] ( listen); 14 March 1879 – 18 April 1955) was a German-born theoretical physicist who developed the theory of general relativity, effecting a revolution in physics. For this achievement, Einstein is often regarded as the father of modern physics.[2] He received the 1921 Nobel Prize in Physics "for his services to theoretical physics, and especially for his discovery of the law of the photoelectric effect". [3] The latter was pivotal in establishing quantum theory within physics. Near the beginning of his career, Einstein thought that Newtonian mechanics was no longer enough to reconcile the laws of classical mechanics with the laws of the electromagnetic field. This led to the development of his special theory of relativity. He Albert Einstein in 1921 realized, however, that the principle of relativity could also be extended to gravitational fields, and with his Born 14 March 1879 subsequent theory of gravitation in 1916, he published Ulm, Kingdom of Württemberg, a paper on the general theory of relativity. He German Empire continued to deal with problems of statistical Died mechanics and quantum theory, which led to his 18 April 1955 (aged 76) explanations of particle theory and the motion of Princeton, New Jersey, United States molecules. He also investigated the thermal properties Residence Germany, Italy, Switzerland, United of light which laid the foundation of the photon theory States of light. In 1917, Einstein applied the general theory of relativity to model the structure of the universe as a Ethnicity Jewish [4] whole. -

What Physics Should We Teach?

Proceedings of the International Physics Education Conference, 5 to 8 July 2004, Durban, South Africa What Physics Should We Teach? Edited by Diane J. Grayson Sponsored by the International Commission on Physics Education and the South African Institute of Physics International Advisory Committee Igal Galili (Israel) Priscilla Laws (USA) Inocente Multimucuio (Mozambique) Jon Ogborn (UK) Joe Redish (USA) Khalijah Salleh (Malaysia) David Schuster (USA/ South Africa) Gunnar Tibell (Sweden) Matilde Vicentini (Italy) Laurence Viennot (France) Conference Organiser Diane Grayson Local Organisers Sandile Malinga Jaynie Padayachee Sadha Pillay. Robynne Savic and Carmen Fitzgerald (Interaction Conferencing) Editorial Assistant Erna Basson Administrative Assistant Ignatious Dire Cover Design: Joerg Ludwig © 2005 International Commission on Physics Education ISBN 1-86888-359 University of South Africa Press, PO Box 392, UNISA 0003, South Africa TABLE OF CONTENTS INTRODUCTION....................................................................................................................... 2 Citation for the Presentation of the Medal.................................................................................... 6 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS......................................................................................................... 7 PAPERS BY PLENARY SPEAKERS ........................................................................................ 8 QUANTUM GRAVITY FOR UNDERGRADUATES? .............................................................