Women's Lives

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

2019 LS Polling Stations and Constituencies.Xlsx

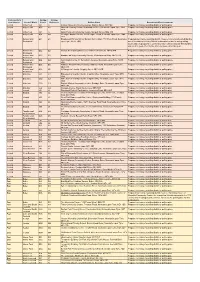

Parliamentary Polling Polling Constituency Council Ward District Reference Polling Place Returning Officer Comments Central Arthur's Hill A01 A1 Stanton Street Community Lounge, Stanton Street, NE4 5LH Propose no change to polling district or polling place Central Arthur's Hill A02 A2 Moorside Primary School, Beaconsfield Street, Newcastle upon Tyne, NE4 Propose no change to polling district or polling place 5AW Central Arthur's Hill A03 A3 Spital Tongues Community Centre, Morpeth Street, NE2 4AS Propose no change to polling district or polling place Central Arthur's Hill A04 A4 Westgate Baptist Church, 366 Westgate Road, Newcastle upon Tyne, NE4 Propose no change to polling district or polling place 6NX Central Benwell and B01 B1 Broadwood Primary School Denton Burn Library, 713 West Road, Newcastle Proposed no change to polling district, however it is recommended that the Scotswood upon Tyne, NE15 7QQ use of Broadwood Primary School is discontinued due to safeguarding issues and it is proposed to use Denton Burn Library instead. This building was used to good effect for the PCC elections earlier this year. Central Benwell and B02 B2 Denton Burn Methodist Church, 615-621 West Road, NE15 7ER Propose no change to polling district or polling place Scotswood Central Benwell and B03 B3 Broadmead Way Community Church, 90 Broadmead Way, NE15 6TS Propose no change to polling district or polling place Scotswood Central Benwell and B04 B4 Sunnybank Centre, 14 Sunnybank Avenue, Newcastle upon Tyne, NE15 Propose no change to polling district or -

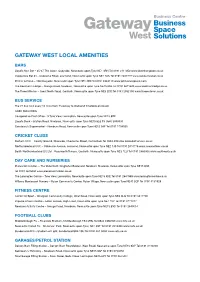

Gateway West Local Amenities

GATEWAY WEST LOCAL AMENITIES BARS Lloyd’s No1 Bar – 35-37 The Close, Quayside, Newcastle upon Tyne NE1 3RN Tel 0191 2111050 www.jdwetherspoon.co.uk Osbournes Bar 61 - Osbourne Road, Jesmond, Newcastle upon Tyne NE2 2AN Tel 0191 2407778 www.osbournesbar.co.uk Pitcher & Piano – 108 Quayside, Newcastle upon Tyne NE1 3DX Tel 0191 2324110 www.pitcherandpiano.com The Keelman’s Lodge – Grange Road, Newburn, Newcastle upon Tyne NE15 8NL Tel 0191 2671689 www.keelmanslodge.co.uk The Three Mile Inn – Great North Road, Gosforth, Newcastle upon Tyne NE3 2DS Tel 0191 2552100 www.threemileinn.co.uk BUS SERVICE The 22 bus runs every 10 mins from Throckley to Wallsend timetable enclosed CASH MACHINES Co-operative Post Office - 9 Tyne View, Lemington, Newcastle upon Tyne NE15 8DE Lloyd’s Bank – Station Road, Newburn, Newcastle upon Tyne NE15 8LS Tel 0845 3000000 Sainsbury’s Supermarket - Newburn Road, Newcastle upon Tyne NE15 9AF Tel 0191 2754050 CRICKET CLUBS Durham CCC – County Ground, Riverside, Chester-le-Street, Co Durham Tel 0844 4994466 www.durhamccc.co.uk Northumberland CCC – Osbourne Avenue, Jesmond, Newcastle upon Tyne NE2 1JS Tel 0191 2810775 www.newcastlecc.co.uk South Northumberland CC Ltd – Roseworth Terrace, Gosforth, Newcastle upon Tyne NE3 1LU Tel 0191 2460006 www.southnort.co.uk DAY CARE AND NURSERIES Places for Children – The Waterfront, Kingfisher Boulevard, Newburn Riverside, Newcastle upon Tyne NE15 8NZ Tel 0191 2645030 www.placesforchildren.co.uk The Lemington Centre – Tyne View, Lemington, Newcastle upon Tyne NE15 8DE Tel 0191 2641959 -

Geological Notes and Local Details for 1:Loooo Sheets NZ26NW, NE, SW and SE Newcastle Upon Tyne and Gateshead

Natural Environment Research Council INSTITUTE OF GEOLOGICAL SCIENCES Geological Survey of England and Wales Geological notes and local details for 1:lOOOO sheets NZ26NW, NE, SW and SE Newcastle upon Tyne and Gateshead Part of 1:50000 sheets 14 (Morpeth), 15 (Tynemouth), 20 (Newcastle upon Tyne) and 21 (Sunderland) G. Richardson with contributions by D. A. C. Mills Bibliogrcphic reference Richardson, G. 1983. Geological notes and local details for 1 : 10000 sheets NZ26NW, NE, SW and SE (Newcastle upon Tyne and Gateshead) (Keyworth: Institute of Geological Sciences .) Author G. Richardson Institute of Geological Sciences W indsorTerrace, Newcastle upon Tyne, NE2 4HE Production of this report was supported by theDepartment ofthe Environment The views expressed in this reportare not necessarily those of theDepartment of theEnvironment - 0 Crown copyright 1983 KEYWORTHINSTITUTE OF GEOLOGICALSCIENCES 1983 PREFACE "his account describes the geology of l:25 000 sheet NZ 26 which spans the adjoining corners of l:5O 000 geological sheets 14 (Morpeth), 15 (Tynemouth), 20 (Newcastle upon Tyne) and sheet 22 (Sunderland). The area was first surveyed at a scale of six inches to one mile by H H Howell and W To~ley. Themaps were published in the old 'county' series during the years 1867 to 1871. During the first quarter of this century parts of the area were revised but no maps were published. In the early nineteen twenties part of the southern area was revised by rcJ Anderson and published in 1927 on the six-inch 'County' edition of Durham 6 NE. In the mid nineteen thirties G Burnett revised a small part of the north of the area and this revision was published in 1953 on Northumberland New 'County' six-inch maps 85 SW and 85 SE. -

Keith Hill on Keith Hill

June 1, 2015, Issue 450 Addressing SaladGate Six pages of in-depth reporting on Women In Country and a post-CRS panel write-up in which Keith Hill urged slashing female- voiced songs made nary a ripple outside the business a few months back. But the consultant’s lettuce-and-tomatoes analogy last week in this space touched off a social and, eventually, major media tidal wave. Go figure. We’ll get to Hill in the next story (right), after female PDs and MDs weigh in with their thoughts on a well-known though still confounding reality. In full disclosure, some of the women we contacted declined to contribute for lack of time or lack of what they felt would be helpful feedback. Some passed because they weren’t comfortable publicly commenting in a “no-win argument.” And some came to us asking to be part of the conversation. Lost In Translation: “I don’t think he phrased what he was trying to say especially well,” says Scripps/ Spark Plug: Big Spark/Star Farm’s Olivia Lane hosts industry Tulsa OM and KVOO PD Jules Riley, whose pros at Handlebar J in Phoenix over the weekend. Pictured station has averaged 9% female current/ (front, l-r) are Big Spark’s Dennis Kurtz, Handlebar J’s Ray Herndon, Susan Pohlman (wife of KMLE/Phoenix’s Tim recurrent airplay and 14% in gold since Jan.1, Pohlman), KIIM/Tucson’s Buzz Jackson and wife Dena, KTGX/ according to Mediabase 24/7. “It did strike a Tulsa’s Kristina Carlyle, Lane, KTEX/McAllen’s JoJo Cerda little bit of a nerve. -

Constituency Ward District Reference Polling Place Returning Officer Comments

Constituency Ward District Reference Polling Place Returning Officer Comments Central Arthurs Hill A01 A1 Stanton Street Community Lounge, Stanton Street, NE4 5LH Propose no change to polling district or polling place Moorside Primary School, Beaconsfield Street, Newcastle upon Tyne, NE4 Central Arthurs Hill A02 A2 Propose no change to polling district or polling place 5AW Central Arthurs Hill A03 A3 Spital Tongues Community Centre, Morpeth Street, NE2 4AS Propose no change to polling district or polling place Westgate Baptist Church, 366 Westgate Road, Newcastle upon Tyne, NE4 Central Arthurs Hill A04 A4 Propose no change to polling district or polling place 6NX Proposed no change to polling district, however it is recommended that the Benwell and Broadwood Primary School Denton Burn Library, 713 West Road, Newcastle use of Broadwood Primary School is discontinued due to safeguarding Central B01 B1 Scotswood upon Tyne, NE15 7QQ issues and it is proposed to use Denton Burn Library instead. This building was used to good effect for the PCC elections earlier this year. Benwell and Central B02 B2 Denton Burn Methodist Church, 615-621 West Road, NE15 7ER Propose no change to polling district or polling place Scotswood Benwell and Central B03 B3 Broadmead Way Community Church, 90 Broadmead Way, NE15 6TS Propose no change to polling district or polling place Scotswood Benwell and Central B04 B4 Sunnybank Centre, 14 Sunnybank Avenue, Newcastle upon Tyne, NE15 6SD Propose no change to polling district or polling place Scotswood Benwell and Atkinson -

Vol-14-No-1.Pdf

EDITORIAL Another year has come and gone, and we trust that 1989 will be a happy and prosperous one for all our members. If our Society is to continue to flourish, however, it is essential that more members should play an active part in running its affairs. Ken Brown, our Secretary since 1983 (and acting Programme Organiser for the last year), is resigning at the Annual General Meeting in May, and Irene Blackburn, who is responsible for the Members' Interests and Second Time Around sections of the Journal, will be giving up her position as Research Editor later in the year. We are very grateful to them both for all the work they have done on our behalf. In addition to these two posts, we are still short of a Programme Organiser. If you know of anyone who might be willing to take on any of these jobs please let Ken Brown know as soon as possible - otherwise the Society may come to a grinding halt. One of the most important events of 1988 as far as the Society was concerned was the publication of the long-awaited Directory of Members' Interests. Its production entailed a great deal of hard work on the part of those responsible, and it also placed a severe strain on the Society's finances. In view of the fact that it was initially offered free to members (only the cost of postage and packing being charged), the demand for copies was disappointingly small. Copies are still available, and although now priced £2.75 each (post free to addresses in the U.K.), they are very good value. -

Know Your Councillors 2019 — 2020

Know Your Councillors 2019 — 2020 Arthur’s Hill Benwell & Scotswood Blakelaw Byker Callerton & Throckley Castle Chapel Dene & South Gosforth Denton & Westerhope Ali Avaei Lord Beecham DCL DL Oskar Avery George Allison Ian Donaldson Sandra Davison Henry Gallagher Nick Forbes C/o Members Services Simon Barnes 39 The Drive C/o Members Services 113 Allendale Road Clovelly, Walbottle Road 11 Kelso Close 868 Shields Road c/o Leaders Office Newcastle upon Tyne C/o Members Services Newcastle upon Tyne Newcastle upon Tyne Newcastle upon Tyne Walbottle Chapel Park Newcastle upon Tyne Newcastle upon Tyne NE1 8QH Newcastle upon Tyne NE3 4AJ NE1 8QH NE6 2SY Newcastle upon Tyne Newcastle upon Tyne NE6 4QP NE1 8QH 0191 274 0627 NE1 8QH 0191 285 1888 07554 431 867 0191 265 8995 NE15 8HY NE5 1TR 0191 276 0819 0191 211 5151 07765 256 319 07535 291 334 07768 868 530 Labour Labour 07702 387 259 07946 236 314 07947 655 396 Labour Liberal Democrat Labour Labour Newcastle First Independent Liberal Democrat [email protected] [email protected] [email protected] [email protected] [email protected] [email protected] [email protected] [email protected] [email protected] Marc Donnelly Veronica Dunn Melissa Davis Joanne Kingsland Rob Higgins Nora Casey Stephen Fairlie Aidan King 17 Ladybank Karen Robinson 18 Merchants Wharf 78a Wheatfield Road 34 Valley View 11 Highwood Road C/o Members Services 24 Hawthorn Street 15 Hazelwood Road Newcastle upon Tyne 441 -

Hawthorne Strathmore

TO LET/ MAY SELL HEADQUARTERS OFFICE BUILDINGS HAWTHORNE STRATHMORE FROM 7,000 SQ FT TO 67,000 SQ FT VIKING BUSINESS PARK | JARROW | TYNE & WEAR | NE32 3DP HAWTHORNE STRATHMORE SPECIFICATION Both properties benefit from • Full height atrium • Extensive glazing providing excellent natural • Feature receptions light &LOCATION AND SITUATION • Four pipe fan coil air • Male and female toilet conditioning Hawthorne and Strathmore are located within the facilities on each floor Viking Business Park which is less than ½ mile west of • Full raised access floors Jarrow town centre just to the south of the River Tyne. • Disabled toilet facilities • Suspended ceilings including showers on each The Viking Business Park is well positioned just 4 floor miles east of Newcastle city centre and 3 miles east of • Recessed strip lighting • Car parking ratio of Gateshead town centre. • LED panels in part 1:306 sq ft Access to the rest of the region is excellent with the • Lift access to all floors A19 and Tyne Tunnel being less than 1 mile away, providing easy access to the wider road network as SOUTH TYNESIDE AND well as Newcastle Airport. NORTH EAST FACTS South Tyneside is an area that combines both a • South Tyneside has a population of over 145,000. heritage-filled past and impressive regeneration The wider Tyne and Wear metropolitan area has a projects for the future, presenting opportunities for population of over 1,200,000. businesses to develop as well as good housing, leisure and general amenity for employees. • The average wage within South Tyneside is over 25% less than the national average. -

TO LET 7 Prominent Office/Retail Units

TO LET 7 Prominent Office/Retail Units Tynemouth Station, Tynemouth NE30 4RE sw.co.uk Location The units are situated at Tynemouth Station, which is approximately 9 miles to the east of Newcastle City Centre and 3 miles south of Whitley Bay. One of the oldest stations on the Tyne and Wear Network, this Grade II* listed building was originally opened in 1882. The station serves the first section of the Metro Network from Tynemouth to Haymarket in Newcastle City Centre. Occupiers in the immediate vicinity include; Kings School, Porters Coffee House, newsagents, physiotherapist, hairdressers and numerous other local retailers. During the weekend Tynemouth Station hosts one of the busiest markets in the North East whereby you will find numerous market stalls selling a wide array of crafts, therefore increasing footfall levels significantly. Description The accommodation comprises 7 ground floor units within the Grade II* Tynemouth Station. Parking is not provided with the units although public parking is to the rear. The units are accessed by one shared entrance although there is an option for separate entrances. WC’s and kitchen facilities are also shared with access off the main corridor. The property is of traditional Units ranging from 326 sq ft to 695 sq ft construction with white outer façade. Each unit benefits from a glass frontage facing onto the Metro tracks. Prime location Energy Performance Certificate Rent on application An Energy Performance Certificate has been commissioned and will be available upon completion Terms to be agreed of the proposed refurbishment works which are scheduled to be complete by July 2018. -

The London Gazette, November 20, 1860

4344 THE LONDON GAZETTE, NOVEMBER 20, 1860. relates to each of the parishes in or through which the Ecclesiastical Commissioners for England, and the said intended railway and works will be made, in the occupation of the lessees of Tyne Main together with a copy of the said Gazette Notice, Colliery, with an outfall or offtake drift or water- will be deposired for public inspection with the course, extending from the said station to a p >int parish clerk of each such parish at his residence : immediately eastward of the said station ; on a and in the case of any extra-parochial place with rivulet or brook, in the chapelry of Heworth, in the parish clerk of some parish immediately ad- the parish of Jarrow, and which flows into the joining thereto. river Tyne, in the parish of St Nicholas aforesaid. Printed copies of the said intended Bill will, on A Pumping Station, with shafts, engines, and or before the 23rd day of December next, be de- other works, at or near a place called the B Pit, posited in the Private Bill Office of the House of at Hebburn Colliery, in the township of Helburn, Commons. in the parish of Jarrow, on land belonging to Dated this eighth day of November, one thou- Lieutenant-Colonel Ellison, and now in the occu- sand eight hundred and sixty. pation of the lessees of Hebburn Colliery, with an F. F. Jeyes} 22, Bedford-row, Solicitor for outfall or offtake drift or watercourse, extending the Bill. from the said station to the river Tyne aforesaid, at or near a point immediately west of the Staith, belonging to the said Hebburn Colliery. -

Whickham View City Centre Freeman Hospital 38

Whickham View z City Centre z Freeman Hospital 38 via Whickham View, Fergusons Lane, Benwell Village, Fox and Hounds Lane, Pease Avenue,West Road,Westgate Road, Grainger Street, Market Street (West), Pilgrim Street, New Bridge Street West, John Dobson Street, St. Marys Place, Sandyford Road, Jesmond Road, Benton Bank, Stephenson Road, Newton Road, Freeman Road; journeys to Four Lane Ends continue via Freeman Road, Benton Park Road, Four Lane Ends Metro. MONDAY TO FRIDAY ABC Service number 38A 38A 38A 38 38 38 38 38 38 38 38 38 NOTES: A From Silver Lonnen, Netherby Drive at 0431. Whickham View, Terminus 0435 0511 0547 0605 0630 0652 0708 0724 0734 0744 0754 0804 B This journey commences from Chapel House Benwell Village, Pease Avenue 0440 0514 0550 0610 0635 0657 0713 0729 0739 0749 0759 0809 at 0503, and terminates Pilgrim Street at 0526. General Hospital 0445 0519 0555 0616 0642 0704 0720 0736 0746 0756 0806 0816 C This journey commences from Chapel House Central Station, Westgate Rd 0450 0524 0600 0622 0649 0711 0727 0743 0753 0803 0813 0823 at 0539, and terminates Pilgrim Street at 0602. John Dobson Street - - - 0628 0656 0718 0735 0751 0801 0811 0821 0831 Jesmond,Archbold Terrace - - - 0630 0659 0721 0738 0754 0804 0814 0824 0834 Corner House - - - 0635 0704 0726 0743 0759 0809 0819 0829 0839 For a cleaner environment Freeman Hospital - - - 0640 0709 0731 0748 0804 0814 0824 0834 0844 Stagecoach in Newcastle has a no smoking policy Service number 38 38 38 38 38 38 38 38 38 38 38 38 38 38 38 38 Whickham View, Terminus 0814 24 34 44 -

24, Hepple Way, Gosforth, Newcastle Upon Tyne, Ne3

24, HEPPLE WAY, GOSFORTH, NEWCASTLE UPON TYNE, NE3 £750 per month, Unfurnished + £250 inc VAT tenancy paperwork and inventory fee other charges apply*. Convenient Location • 3 Reception Rooms • 4 Bedrooms • Garden • Parking EPC Rating = D Council Tax = E A detached property situated in its own private grounds with mature gardens. Entrance Vestibule – 2.9m x 1.9m Spacious entrance vestibule with coat hooks, radiator and coving to the ceiling. Cloakroom – 1.3m x 1.3m Low level WC, wall mounted wash hand basin with tiled splashback, radiator, vinyl flooring, window to the front. Study – 4.3m x 3.9m Spacious reception room with window to the side of the property, storage cupboard shelving to one wall, radiator, telephone point, and wall mounted gas fire, coving to ceiling. Inner Reception Hall – 3.01m x 2.5m With telephone point, radiator, understairs cupboard, thermostat, coving to ceiling. Sitting Room – 5.4m x 4.5m Light and airy reception room with gas fire, marble inset and timber surround. French doors into the garden, TV aerial point, window to the side, coving to ceiling. Kitchen – 3.8m x 3.3m With a range of wall & floor units with roll top work surface, space for electric cooker, extractor fan, tiled splash back, 1½ stainless steel sink with drainer and mixer tap over, plumbing for dishwasher, window to side, radiator, vinyl flooring. Utility Room – 1.9m x 3.3m With floor unit, stainless steel sink with drainer, plumbing for washing machine, window to the side, doors to into garage, radiator. Dining Room – 4.6m x 3.9m Spacious reception room with dual aspect windows to the front and side, double radiators, coving to ceiling, stripped wood flooring.