Benwell Forty Years On

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

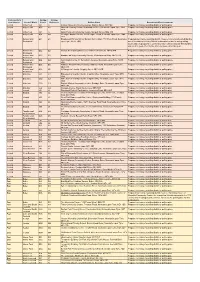

2019 LS Polling Stations and Constituencies.Xlsx

Parliamentary Polling Polling Constituency Council Ward District Reference Polling Place Returning Officer Comments Central Arthur's Hill A01 A1 Stanton Street Community Lounge, Stanton Street, NE4 5LH Propose no change to polling district or polling place Central Arthur's Hill A02 A2 Moorside Primary School, Beaconsfield Street, Newcastle upon Tyne, NE4 Propose no change to polling district or polling place 5AW Central Arthur's Hill A03 A3 Spital Tongues Community Centre, Morpeth Street, NE2 4AS Propose no change to polling district or polling place Central Arthur's Hill A04 A4 Westgate Baptist Church, 366 Westgate Road, Newcastle upon Tyne, NE4 Propose no change to polling district or polling place 6NX Central Benwell and B01 B1 Broadwood Primary School Denton Burn Library, 713 West Road, Newcastle Proposed no change to polling district, however it is recommended that the Scotswood upon Tyne, NE15 7QQ use of Broadwood Primary School is discontinued due to safeguarding issues and it is proposed to use Denton Burn Library instead. This building was used to good effect for the PCC elections earlier this year. Central Benwell and B02 B2 Denton Burn Methodist Church, 615-621 West Road, NE15 7ER Propose no change to polling district or polling place Scotswood Central Benwell and B03 B3 Broadmead Way Community Church, 90 Broadmead Way, NE15 6TS Propose no change to polling district or polling place Scotswood Central Benwell and B04 B4 Sunnybank Centre, 14 Sunnybank Avenue, Newcastle upon Tyne, NE15 Propose no change to polling district or -

Geological Notes and Local Details for 1:Loooo Sheets NZ26NW, NE, SW and SE Newcastle Upon Tyne and Gateshead

Natural Environment Research Council INSTITUTE OF GEOLOGICAL SCIENCES Geological Survey of England and Wales Geological notes and local details for 1:lOOOO sheets NZ26NW, NE, SW and SE Newcastle upon Tyne and Gateshead Part of 1:50000 sheets 14 (Morpeth), 15 (Tynemouth), 20 (Newcastle upon Tyne) and 21 (Sunderland) G. Richardson with contributions by D. A. C. Mills Bibliogrcphic reference Richardson, G. 1983. Geological notes and local details for 1 : 10000 sheets NZ26NW, NE, SW and SE (Newcastle upon Tyne and Gateshead) (Keyworth: Institute of Geological Sciences .) Author G. Richardson Institute of Geological Sciences W indsorTerrace, Newcastle upon Tyne, NE2 4HE Production of this report was supported by theDepartment ofthe Environment The views expressed in this reportare not necessarily those of theDepartment of theEnvironment - 0 Crown copyright 1983 KEYWORTHINSTITUTE OF GEOLOGICALSCIENCES 1983 PREFACE "his account describes the geology of l:25 000 sheet NZ 26 which spans the adjoining corners of l:5O 000 geological sheets 14 (Morpeth), 15 (Tynemouth), 20 (Newcastle upon Tyne) and sheet 22 (Sunderland). The area was first surveyed at a scale of six inches to one mile by H H Howell and W To~ley. Themaps were published in the old 'county' series during the years 1867 to 1871. During the first quarter of this century parts of the area were revised but no maps were published. In the early nineteen twenties part of the southern area was revised by rcJ Anderson and published in 1927 on the six-inch 'County' edition of Durham 6 NE. In the mid nineteen thirties G Burnett revised a small part of the north of the area and this revision was published in 1953 on Northumberland New 'County' six-inch maps 85 SW and 85 SE. -

Constituency Ward District Reference Polling Place Returning Officer Comments

Constituency Ward District Reference Polling Place Returning Officer Comments Central Arthurs Hill A01 A1 Stanton Street Community Lounge, Stanton Street, NE4 5LH Propose no change to polling district or polling place Moorside Primary School, Beaconsfield Street, Newcastle upon Tyne, NE4 Central Arthurs Hill A02 A2 Propose no change to polling district or polling place 5AW Central Arthurs Hill A03 A3 Spital Tongues Community Centre, Morpeth Street, NE2 4AS Propose no change to polling district or polling place Westgate Baptist Church, 366 Westgate Road, Newcastle upon Tyne, NE4 Central Arthurs Hill A04 A4 Propose no change to polling district or polling place 6NX Proposed no change to polling district, however it is recommended that the Benwell and Broadwood Primary School Denton Burn Library, 713 West Road, Newcastle use of Broadwood Primary School is discontinued due to safeguarding Central B01 B1 Scotswood upon Tyne, NE15 7QQ issues and it is proposed to use Denton Burn Library instead. This building was used to good effect for the PCC elections earlier this year. Benwell and Central B02 B2 Denton Burn Methodist Church, 615-621 West Road, NE15 7ER Propose no change to polling district or polling place Scotswood Benwell and Central B03 B3 Broadmead Way Community Church, 90 Broadmead Way, NE15 6TS Propose no change to polling district or polling place Scotswood Benwell and Central B04 B4 Sunnybank Centre, 14 Sunnybank Avenue, Newcastle upon Tyne, NE15 6SD Propose no change to polling district or polling place Scotswood Benwell and Atkinson -

Know Your Councillors 2019 — 2020

Know Your Councillors 2019 — 2020 Arthur’s Hill Benwell & Scotswood Blakelaw Byker Callerton & Throckley Castle Chapel Dene & South Gosforth Denton & Westerhope Ali Avaei Lord Beecham DCL DL Oskar Avery George Allison Ian Donaldson Sandra Davison Henry Gallagher Nick Forbes C/o Members Services Simon Barnes 39 The Drive C/o Members Services 113 Allendale Road Clovelly, Walbottle Road 11 Kelso Close 868 Shields Road c/o Leaders Office Newcastle upon Tyne C/o Members Services Newcastle upon Tyne Newcastle upon Tyne Newcastle upon Tyne Walbottle Chapel Park Newcastle upon Tyne Newcastle upon Tyne NE1 8QH Newcastle upon Tyne NE3 4AJ NE1 8QH NE6 2SY Newcastle upon Tyne Newcastle upon Tyne NE6 4QP NE1 8QH 0191 274 0627 NE1 8QH 0191 285 1888 07554 431 867 0191 265 8995 NE15 8HY NE5 1TR 0191 276 0819 0191 211 5151 07765 256 319 07535 291 334 07768 868 530 Labour Labour 07702 387 259 07946 236 314 07947 655 396 Labour Liberal Democrat Labour Labour Newcastle First Independent Liberal Democrat [email protected] [email protected] [email protected] [email protected] [email protected] [email protected] [email protected] [email protected] [email protected] Marc Donnelly Veronica Dunn Melissa Davis Joanne Kingsland Rob Higgins Nora Casey Stephen Fairlie Aidan King 17 Ladybank Karen Robinson 18 Merchants Wharf 78a Wheatfield Road 34 Valley View 11 Highwood Road C/o Members Services 24 Hawthorn Street 15 Hazelwood Road Newcastle upon Tyne 441 -

The London Gazette, November 20, 1860

4344 THE LONDON GAZETTE, NOVEMBER 20, 1860. relates to each of the parishes in or through which the Ecclesiastical Commissioners for England, and the said intended railway and works will be made, in the occupation of the lessees of Tyne Main together with a copy of the said Gazette Notice, Colliery, with an outfall or offtake drift or water- will be deposired for public inspection with the course, extending from the said station to a p >int parish clerk of each such parish at his residence : immediately eastward of the said station ; on a and in the case of any extra-parochial place with rivulet or brook, in the chapelry of Heworth, in the parish clerk of some parish immediately ad- the parish of Jarrow, and which flows into the joining thereto. river Tyne, in the parish of St Nicholas aforesaid. Printed copies of the said intended Bill will, on A Pumping Station, with shafts, engines, and or before the 23rd day of December next, be de- other works, at or near a place called the B Pit, posited in the Private Bill Office of the House of at Hebburn Colliery, in the township of Helburn, Commons. in the parish of Jarrow, on land belonging to Dated this eighth day of November, one thou- Lieutenant-Colonel Ellison, and now in the occu- sand eight hundred and sixty. pation of the lessees of Hebburn Colliery, with an F. F. Jeyes} 22, Bedford-row, Solicitor for outfall or offtake drift or watercourse, extending the Bill. from the said station to the river Tyne aforesaid, at or near a point immediately west of the Staith, belonging to the said Hebburn Colliery. -

Green Spaces . . . Using Planning

Green spaces . using planning Assessing local needs and standards Green spaces…your spaces Background paper: Green Spaces…using planning PARKS AND GREEN SPACES STRATEGY BACKGROUND PAPER GREEN SPACES…USING PLANNING: ASSESSING LOCAL NEEDS AND STANDARDS _____________________________________________________________ Green Spaces Strategy Team April 2004 City Design, Neighbourhood Services Newcastle City Council CONTENTS 1 Introduction 2 Planning Policy Guidance Note 17 3 National and Local Standards 4 Density and housing types in Newcastle 3 Newcastle’s people 6 Assessing Newcastle's Green Space Needs 7 Is Newcastle short of green space? 8 Identifying “surplus” green space 9 Recommendations Annexe A Current Local, Core Cities and Beacon Council standards ( Quantity of green space, distances to green spaces and quality) Annexe B English Nature's Accessible Natural Green Space standards Annexe C Sample Areas Analysis; Newcastle's house type, density and open space provision. Annexe D Surveys and research Annexe E References and acknowledgements 2 1 Introduction 1.1 We need to consider whether we need standards for green spaces in Newcastle. What sort of standards, and how to apply them. 1.2 Without standards there is no baseline against which provision can be measured. It is difficult to make a case against a proposal to build on or change the use of existing open space or a case for open space to be included in a development scheme if there are no clear and agreed standards. 1.3 Standards are used to define how much open space is needed, particularly when planning new developments. Local authority planning and leisure departments have developed standards of provision and these have been enshrined in policy and guidance documents. -

Northumberland and Durham Family History Society Unwanted

Northumberland and Durham Family History Society baptism birth marriage No Gsurname Gforename Bsurname Bforename dayMonth year place death No Bsurname Bforename Gsurname Gforename dayMonth year place all No surname forename dayMonth year place Marriage 933ABBOT Mary ROBINSON James 18Oct1851 Windermere Westmorland Marriage 588ABBOT William HADAWAY Ann 25 Jul1869 Tynemouth Marriage 935ABBOTT Edwin NESS Sarah Jane 20 Jul1882 Wallsend Parrish Church Northumbrland Marriage1561ABBS Maria FORDER James 21May1861 Brooke, Norfolk Marriage 1442 ABELL Thirza GUTTERIDGE Amos 3 Aug 1874 Eston Yorks Death 229 ADAM Ellen 9 Feb 1967 Newcastle upon Tyne Death 406 ADAMS Matilda 11 Oct 1931 Lanchester Co Durham Marriage 2326ADAMS Sarah Elizabeth SOMERSET Ernest Edward 26 Dec 1901 Heaton, Newcastle upon Tyne Marriage1768ADAMS Thomas BORTON Mary 16Oct1849 Coughton Northampton Death 1556 ADAMS Thomas 15 Jan 1908 Brackley, Norhants,Oxford Bucks Birth 3605 ADAMS Sarah Elizabeth 18 May 1876 Stockton Co Durham Marriage 568 ADAMSON Annabell HADAWAY Thomas William 30 Sep 1885 Tynemouth Death 1999 ADAMSON Bryan 13 Aug 1972 Newcastle upon Tyne Birth 835 ADAMSON Constance 18 Oct 1850 Tynemouth Birth 3289ADAMSON Emma Jane 19Jun 1867Hamsterley Co Durham Marriage 556 ADAMSON James Frederick TATE Annabell 6 Oct 1861 Tynemouth Marriage1292ADAMSON Jane HARTBURN John 2Sep1839 Stockton & Sedgefield Co Durham Birth 3654 ADAMSON Julie Kristina 16 Dec 1971 Tynemouth, Northumberland Marriage 2357ADAMSON June PORTER William Sidney 1May 1980 North Tyneside East Death 747 ADAMSON -

Local Bus Links in Newcastle Designing a Network To

Local bus links in Newcastle Designing a network to TYNE AND WEAR meet your needs INTEGRATED TRANSPORT AUTHORITY Public consultation 15 March - 4 June 2010 Local bus links in Newcastle Designing a network to meet your needs Public consultation People in Newcastle make 47 million bus journeys annually - that’s an average of more than 173 journeys a year for every resident! Nexus, Newcastle City Council and the Tyne and Wear Integrated Transport Authority (ITA) want to make sure the network of bus services in the area meets residents’ needs. To do this, Nexus has worked together with bus companies and local councils to examine how current services operate and to look at what improvements could be made to the ‘subsidised’ services in the network, which are the ones Nexus pays for. We have called this the Accessible Bus Network Design Project (see below). We want your views on the proposals we are now making to improve bus services in Newcastle, which you can find in this document. We want to hear from you whether you rely on the bus in your daily life, use buses only occasionally or even if you don’t – but might consider doing so in the future. You’ll find details of different ways to respond on the back page of this brochure. This consultation forms part of the Tyne and Wear Integrated Transport Authority’s Bus Strategy, a three year action plan to improve all aspects of the bus services in Tyne and Wear. Copies of the Bus Strategy can be downloaded from www.nexus.org.uk/busstrategy. -

Brough Park BROUGH PARK TRADING ESTATE N FOSSWAY N NEWCASTLE UPON TYNE N NE6 2YF

Brough Park BROUGH PARK TRADING ESTATE n FOSSWAY n NEWCASTLE UPON TYNE n NE6 2YF Trade counter/ Central location only 2 miles east of Newcastle City Centre Units available from 736 m2 (7,917 sq. ft.) to warehouse units 2,206 m2 (23,744 sq. ft.) Thomas Owen & Sons (Newcastle) Ltd Neal Lawrence Conlon NEWCASTLE UPON TYNE www.brindustrialtrust.com/broughpark Brough Park Trading Estate Description Services The Brough Park Trading Estate, which is benefiting from n The units are provided with mains supplies of gas, a comprehensive upgrade program, comprises a series of water and three phase electricity. portal framed units arranged in three terraced blocks. Each are constructed having cavity brickwork walls with high n Lighting throughout the units is predominantly by level insulated cladding. The roof areas are double pitched fluorescent strips. with an insulated profile sheeted covering incorporating translucent rooflights. n A number of the units have gas fired, warm air blowers to the warehouse space whilst the office Internally the units have a clear height of 5m and incorpo- space is heated by way of gas fired boilers serving rate both ladies and gents WC facilities and a range of office panel radiators to the larger units and by way of space which varies in relation to the size of the unit. electric heaters to the smaller units. Externally the units have a concrete apron and parking area to the front which provides vehicular access by way of steel roller shutter loading doors each 4.8m wide x 4.6m high. NEWCASTLE UPON TYNE N Accommodation/Occupiers Unit Area Area Tenant Name No. -

Local Election Results 2007

Local Election Results 3rd May 2007 Tyne and Wear Andrew Teale Version 0.05 April 29, 2009 2 LOCAL ELECTION RESULTS 2007 Typeset by LATEX Compilation and design © Andrew Teale, 2007. The author grants permission to copy and distribute this work in any medium, provided this notice is preserved. This file (in several formats) is available for download from http://www.andrewteale.me.uk/ Please advise the author of any corrections which need to be made by email: [email protected] Chapter 4 Tyne and Wear 4.1 Gateshead Birtley Deckham Neil Weatherley Lab 1,213 Bernadette Oliphant Lab 1,150 Betty Gallon Lib 814 Daniel Carr LD 398 Andrea Gatiss C 203 Allan Davidson C 277 Kevin Scott BNP 265 Blaydon (2) Malcolm Brain Lab 1,338 Dunston and Teams Stephen Ronchetti Lab 1,047 Mark Gardner LD 764 Maureen Clelland Lab 940 Colin Ball LD 543 Michael Ruddy LD 357 Trevor Murray C 182 Andrew Swaddle BNP 252 Margaret Bell C 179 Bridges Bob Goldsworthy Lab 888 Dunston Hill and Whickham East Peter Andras LD 352 George Johnson BNP 213 Yvonne McNicol LD 1,603 Ada Callanan C 193 Gary Haley Lab 1,082 John Callanan C 171 Chopwell and Rowlands Gill Saira Munro BNP 165 Michael McNestry Lab 1,716 Raymond Callender LD 800 Maureen Moor C 269 Felling Kenneth Hutton BNP 171 Paul McNally Lab 1,149 David Lucas LD 316 Chowdene Keith McFarlane BNP 205 Steve Wraith C 189 Keith Wood Lab 1,523 Daniel Duggan C 578 Glenys Goodwill LD 425 Terrence Jopling BNP 231 High Fell Malcolm Graham Lab 1,100 Crawcrook and Greenside Ann McCarthy LD 250 Derek Anderson LD 1,598 Jim Batty UKIP 194 Helen Hughes Lab 1,084 June Murray C 157 Leonard Davidson C 151 Ronald Fairlamb BNP 151 48 4.1. -

S104 Bus Time Schedule & Line Route

S104 bus time schedule & line map S104 Arthur's Hill - Scotswood View In Website Mode The S104 bus line Arthur's Hill - Scotswood has one route. For regular weekdays, their operation hours are: (1) Scotswood: 7:45 AM Use the Moovit App to ƒnd the closest S104 bus station near you and ƒnd out when is the next S104 bus arriving. Direction: Scotswood S104 bus Time Schedule 23 stops Scotswood Route Timetable: VIEW LINE SCHEDULE Sunday Not Operational Monday 7:45 AM Stanhope Street-Social Club, Arthur's Hill Avolon Place, Newcastle Upon Tyne Tuesday 7:45 AM Stanhope Street-Avison Street, Arthur's Hill Wednesday 7:45 AM Avison Place, Newcastle Upon Tyne Thursday 7:45 AM Stanhope Street-Baxterwood Court, Arthur's Hill Friday 7:45 AM Frosterley Place, Newcastle Upon Tyne Saturday Not Operational Stanhope Street-Stanton Street, Arthur's Hill Stanhope Street-Brighton Grove, Arthur's Hill 17 Brighton Grove, Newcastle Upon Tyne S104 bus Info Arthur's Hill-Brighton Grove, Arthur's Hill Direction: Scotswood 7 Westgate Road, Newcastle Upon Tyne Stops: 23 Trip Duration: 30 min Newcastle C.A.V Campus, Fenham Line Summary: Stanhope Street-Social Club, Arthur's Hill, Stanhope Street-Avison Street, Arthur's Hill, Newcastle C.A.V Campus, Fenham Stanhope Street-Baxterwood Court, Arthur's Hill, Stanhope Street-Stanton Street, Arthur's Hill, West Road-The Plaza, Fenham Stanhope Street-Brighton Grove, Arthur's Hill, Arthur's Hill-Brighton Grove, Arthur's Hill, Newcastle West Road-Colston Street, Fenham C.A.V Campus, Fenham, Newcastle C.A.V Campus, Fenham, West -

Belonging in Byker

Belonging in Byker The Nature of Local Belonging and Attachment in Contemporary Cities Sophie K. Yarker PhD Thesis Submitted July 2014 School of Geography, Politics and Sociology Newcastle University Contents Contents List of figures vi Acknowledgements viii Abstract ix Chapter 1. Belonging in Byker 1 1.1 Do we still Belong? 3 1.2 Geography Matters 5 1.3 The Lure of the Local 8 1.4 Regenerating Local Identities 11 1.5 Summary 13 1.6 Structure of Thesis 14 Chapter 2. Geographies of Belonging in the Everyday Experience of Place 17 2.1 Nature of Belonging in Human Geography 18 2.2.1 Belonging and Mobility 20 2.2 The Lure of the Local 25 2.3 Theorising the Local 32 2.3.1 A Complimentary Theorisation of Place 33 2.3.2 The Production of Space 35 2.4 Theorising Belonging: How People Belong 37 i 2.4.1 The Everyday Experience of Belonging 39 2.4.2 How do People Practice Everyday Belonging 43 2.4.3 Everyday affects and ‘Local Structure of Feeling’ 47 2.5 Theorising Belonging: Why People Belong 52 2.5.1 Physical Environment 53 2.5.2 Social and Socio-demographic Factors 58 2.5.3 Cultural Factors 66 2.5.4 Auto-biographies 70 2.6 Conclusions 71 Chapter 3. Researching the Lived Experience of Place 76 3.1 The Byker Estate 76 3.2 Meet the Participants 84 3.3 ‘Getting at’ the Local 90 3.3.1 Looking 95 3.3.2 Talking 97 3.3.3 Walking 103 3.3.4 Listening 104 3.3.5 Summary of Methods 105 3.4 Reflections 106 3.4.1 Matters of Place 106 3.4.2 Positionality: Local, but not local enough 108 ii 3.5 Moving from Data to Theory, and back again 109 3.6 Conclusions 112 Chapter 4.