Dilated Cardiomyopathy

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Myocarditis and Cardiomyopathy

CE: Tripti; HCO/330310; Total nos of Pages: 6; HCO 330310 REVIEW CURRENT OPINION Myocarditis and cardiomyopathy Jonathan Buggey and Chantal A. ElAmm Purpose of review The aim of this study is to summarize the literature describing the pathogenesis, diagnosis and management of cardiomyopathy related to myocarditis. Recent findings Myocarditis has a variety of causes and a heterogeneous clinical presentation with potentially life- threatening complications. About one-third of patients will develop a dilated cardiomyopathy and the pathogenesis is a multiphase, mutlicompartment process that involves immune activation, including innate immune system triggered proinflammatory cytokines and autoantibodies. In recent years, diagnosis has been aided by advancements in cardiac MRI, and in particular T1 and T2 mapping sequences. In certain clinical situations, endomyocardial biopsy (EMB) should be performed, with consideration of left ventricular sampling, for an accurate diagnosis that may aid treatment and prognostication. Summary Although overall myocarditis accounts for a minority of cardiomyopathy and heart failure presentations, the clinical presentation is variable and the pathophysiology of myocardial damage is unique. Cardiac MRI has significantly improved diagnostic abilities, but endomyocardial biopsy remains the gold standard. However, current treatment strategies are still focused on routine heart failure pharmacotherapies and supportive care or cardiac transplantation/mechanical support for those with end-stage heart failure. Keywords cardiac MRI, cardiomyopathy, endomyocardial biopsy, myocarditis INTRODUCTION prevalence seen in children and young adults aged Myocarditis refers to inflammation of the myocar- 20–30 years [1]. dium and may be caused by infectious agents, systemic diseases, drugs and toxins, with viral infec- CAUSE tions remaining the most common cause in the developed countries [1]. -

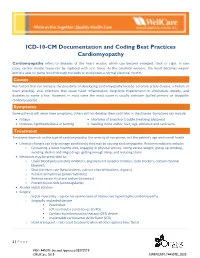

ICD-10-CM Documentation and Coding Best Practices

ICD-10-CM Documentation and Coding Best Practices Cardiomyopathy Cardiomyopathy refers to diseases of the heart muscle, which can become enlarged, thick or rigid. In rare cases, cardiac muscle tissue can be replaced with scar tissue. As the condition worsens, the heart becomes weaker and less able to pump blood through the body or to maintain a normal electrical rhythm. Causes Risk factors that can increase the possibility of developing cardiomyopathy include: coronary artery disease, a history of heart attack (s), viral infections that cause heart inflammation, long-term hypertension or alcoholism, obesity, and diabetes to name a few. However, in most cases the exact cause is usually unknown (called primary or idiopathic cardiomyopathy). Symptoms Some patients will never have symptoms; others will not develop them until later in the disease. Symptoms can include: • Fatigue • Shortness of b reath or trouble breathing (dyspnea) • Dizziness, lightheadedness or fainting • Swelling in the ankles, feet, legs, abdomen and neck veins Treatment Treatment depends on the type of cardiomyopathy, the severity of symptoms, and the patient’s age and overall health. • Lifestyle changes can help manage condition(s) that may be causing cardiomyopathy. Recommendations include: o Consuming a heart healthy diet, engaging in physical activity, losing excess weight, giving up smoking, avoiding alcohol and illegal drugs, getting enough sleep, and reducing stress • Medicines may be p rescribed to: o Lower blood pressure (ACE inhibitors, angiotensin II receptor blo ckers, beta blockers, calcium channel blockers ) o Slow the heart rate (beta blockers, calcium channel blockers, digoxin) o Prevent arrhythmias (antiarrhythmics) o Remove excess fluid and sodium (diuretics) o Prevent blood clots (anticoagulants) • Alcohol septal ablation • Surgery o Septal myectomy – option for severe cases of obstructive hypertrophic cardiomyopathy Surgically implanted devices o . -

An Uncommon Clinical Presentation of Relapsing Dilated Cardiomyopathy with Identification of Sequence Variations in MYNPC3, KCNH2 and Mitochondrial Trna Cysteine M

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by George Washington University: Health Sciences Research Commons (HSRC) Himmelfarb Health Sciences Library, The George Washington University Health Sciences Research Commons Pediatrics Faculty Publications Pediatrics 6-2015 An uncommon clinical presentation of relapsing dilated cardiomyopathy with identification of sequence variations in MYNPC3, KCNH2 and mitochondrial tRNA cysteine M. J. Guillen Sacoto Kimberly A. Chapman George Washington University D. Heath M. B. Seprish Dina Zand George Washington University Follow this and additional works at: http://hsrc.himmelfarb.gwu.edu/smhs_peds_facpubs Part of the Pediatrics Commons Recommended Citation Guillen Sacoto, M.J., Chapman, K.A., Heath, D., Seprish, M.B., Zand, D.J. (2015). An uncommon clinical presentation of relapsing dilated cardiomyopathy with identification of sequence variations in MYNPC3, KCNH2 and mitochondrial tRNA cysteine. Molecular Genetics and Metabolism Reports, 3, 47-54. doi:10.1016/j.ymgmr.2015.03.007 This Journal Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Pediatrics at Health Sciences Research Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Pediatrics Faculty Publications by an authorized administrator of Health Sciences Research Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Molecular Genetics and Metabolism Reports 3 (2015) 47–54 Contents lists available at ScienceDirect Molecular Genetics and Metabolism Reports journal homepage: http://www.journals.elsevier.com/molecular-genetics-and- metabolism-reports/ Case Report An uncommon clinical presentation of relapsing dilated cardiomyopathy with identification of sequence variations in MYNPC3, KCNH2 and mitochondrial tRNA cysteine Maria J. Guillen Sacoto a,1, Kimberly A. -

Coxsackievirus B Detection in Cases of Myocarditis, Myopericarditis, Pericarditis and Dilated Cardiomyopathy in Hospitalized Patients

MOLECULAR MEDICINE REPORTS 10: 2811-2818, 2014 Coxsackievirus B detection in cases of myocarditis, myopericarditis, pericarditis and dilated cardiomyopathy in hospitalized patients IMED GAALOUL1-3*, SAMIRA RIABI1*, RAFIK HARRATH1, TIMOTHY HUNTER2, KHALDOUN B. HAMDA4, ASSIA B. GHZALA5, SALLY HUBER3 and MAHJOUB AOUNI1 1Laboratory of Transmissible Diseases LR99‑ES27, Faculty of Pharmacy, Monastir 5000, Tunisia; 2DNA Microarray Facility, 305 Health Science Research Facility, University of Vermont; 3Department of Pathology, University of Vermont, Burlington, VT 05405, USA; 4Department of Cardiology, University Hospital Fattouma Bourguiba, Monastir 5000; 5Department of Cardiology, University Hospitals Farhat Hached and Sahloul, Sousse 4054, Tunisia Received November 9, 2013; Accepted May 21, 2014 DOI: 10.3892/mmr.2014.2578 Abstract. Coxsackieviruses B (CV-B) are known as the most Introduction common viral cause of human heart infections. The aim of the present study was to assess the potential role of CV-B in the Cardiovascular infections include a group of entities involving etiology of infectious heart disease in hospitalized patients. the heart wall, such as myocarditis, dilated cardiomyopathy The present study is based on blood, pericardial fluid and heart and pericarditis. These processes are associated with high biopsies from 102 patients and 100 control subjects. All of the morbidity and mortality. Although early diagnosis is essential samples were examined for the detection of specific enteroviral for adequate patient management and leads to improved prog- genome using the reverse transcription polymerase chain reac- nosis, the clinical manifestations are often non specific (1). tion (RT-PCR) and sequence analysis. Immunohistochemical Myocarditis is clinically and pathologically defined as investigations for the detection of the enteroviral capsid an inflammation of the heart muscle. -

Etiopathogenesis of Arrhythmogenic Right Ventricular Cardiomyopathy

J Hum Genet (2005) 50:375–381 DOI 10.1007/s10038-005-0273-5 MINIREVIEW Maithili V.N. Dokuparti Æ Pranathi Rao Pamuru Bhavesh Thakkar Æ Reena R. Tanjore Æ Pratibha Nallari Etiopathogenesis of arrhythmogenic right ventricular cardiomyopathy Received: 19 May 2005 / Accepted: 20 June 2005 / Published online: 12 August 2005 Ó The Japan Society of Human Genetics and Springer-Verlag 2005 Abstract Arrhythmogenic right ventricular cardiomy- TGFb-3 for ARVC1 and the role of all these three genes opathy (ARVC) is characterised by progressive fibro- (plakoglobin, desmoplakin and plakophilin) in cardiac fatty replacement of right ventricular myocardium. morphogenesis indicate some kind of signal-transducing Earlier studies described ARVC as non-inflammatory, pathway disruption in the condition. The finding that non-coronary disorder associated with arrhythmias, ARVC as a milder form of Uhl’s anomaly indicates heart failure and sudden death due to functional exclu- similar ontogeny for the condition. Further, discovery of sion of the right ventricle. Molecular genetic studies have apoptotic cells in the autopsy of the right ventricular identified nine different loci associated with ARVC; myocardium of ARVC patients does indicate a common accordingly each locus is implicated for each type of pathway for different types of ARVCs, which is more ARVC (ARVC1–ARVC9). So far five genes have been specific for the right ventricular myocardium involving identified as containing pathogenic mutations for desmosomal plaque proteins, growth factors and Ca2+ ARVC. Though mutations in each of the gene/s indicate receptors. disruption of different pathways leading to the condi- tion, the exact pathogenesis of the condition is still Keywords Etiopathogenesis Æ ARVC Æ Desmosomes Æ obscure. -

Diagnosis and Management of Dilated Cardiomyopathy

Heart 2000;84:106–112 CARDIOMYOPATHY Causes of dilated cardiomyopathy Heart: first published as 10.1136/heart.84.1.106 on 1 July 2000. Downloaded from Young Diagnosis and management of dilated x Myocarditis (infective/toxic/immune) cardiomyopathy x Carnitine deficiency 106 Perry Elliott x Selenium deficiency Department of Cardiological Sciences, x Anomalous coronary arteries St George’s Hospital Medical School, London, UK x Arteriovenous malformations x Kawasaki disease ilated cardiomyopathy is a heart mus- x Endocardial fibroelastosis cle disorder defined by the presence of Da dilated and poorly functioning left x Non-compacted myocardium ventricle in the absence of abnormal loading x Calcium deficiency conditions (hypertension, valve disease) or ischaemic heart disease suYcient to cause glo- x Familial IDC bal systolic impairment. A large number of cardiac and systemic diseases can cause systo- x Barth syndrome lic impairment and left ventricular dilatation, Adolescent/adults but in the majority of patients no identifiable cause is found—hence the term “idiopathic” x Familial IDC dilated cardiomyopathy (IDC). There are experimental and clinical data in animals and x X linked humans suggesting that genetic, viral, and x Alcohol immune factors contribute to the pathophysi- ology of IDC. x Myocarditis (infective/toxic/immune) x Tachycardiomyopathy Diagnosis x Mitochondrial Clinical presentation x Arrhythmogenic right ventricular The first presentation of IDC may be with cardiomyopathy http://heart.bmj.com/ systemic embolism or sudden death, but x Eosinophilic (Churg Strauss syndrome) patients more typically present with signs and symptoms of pulmonary congestion and/or x Drugs—anthracyclines low cardiac output, often on a background of Peripartum exertional symptoms and fatigue for many x months or years before their diagnosis. -

Cardiomyopathy- the Facts

Cardiomyopathy- the facts What is it? Cardiomyopathy means disease of the heart muscle. Different types of cardiomyopathy? If you have cardiomyopathy it may mean that your • Dilated cardiomyopathy heart muscle has become enlarged, thicker or stiff. • Hypertrophic cardiomyopathy If this happens your heart is less able to pump blood • Restrictive cardiomyopathy through your body and you may get abnormal heart • Arrhythmogenic right ventricular dysplasia (ARVD) rhythms. This can lead to heart failure or arrhythmia. In turn, heart failure can cause fluid to build up You can get cardiomyopathy at any age, however if in the lungs, ankles, feet, legs, or abdomen. The you have Barth syndrome you are most likely to get weakening of the heart can also cause other severe this as a baby. Although you can get different types of complications, such as heart valve problems. cardiomyopathy if you have Barth Syndrome the most common type is dilated cardiomyopathy. Tell me more about dilated cardiomyopathy? Having dilated cardiomyopathy means that the left ventricle becomes dilated (stretched). When this happens, the heart muscle becomes weak and thin and is unable to pump blood efficiently around the body. This can lead to fluid building up in the lungs and a feeling of being breathless. This collection of symptoms is known as heart failure. Dilated cardiomyopathy develops slowly, so most people have quite severe symptoms before they are diagnosed. There may also be ‘mitral regurgitation’. This is when some of the blood flows in the wrong direction through the mitral valve, from the left ventricle to the left atrium. How do you get it? What about the future? Cardiomyopathy can be acquired or inherited. -

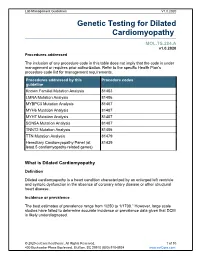

Genetic Testing for Dilated Cardiomyopathy

Lab Management Guidelines V1.0.2020 Genetic Testing for Dilated Cardiomyopathy MOL.TS.284.A v1.0.2020 Procedures addressed The inclusion of any procedure code in this table does not imply that the code is under management or requires prior authorization. Refer to the specific Health Plan's procedure code list for management requirements. Procedures addressed by this Procedure codes guideline Known Familial Mutation Analysis 81403 LMNA Mutation Analysis 81406 MYBPC3 Mutation Analysis 81407 MYH6 Mutation Analysis 81407 MYH7 Mutation Analysis 81407 SCN5A Mutation Analysis 81407 TNNT2 Mutation Analysis 81406 TTN Mutation Analysis 81479 Hereditary Cardiomyopathy Panel (at 81439 least 5 cardiomyopathy-related genes) What is Dilated Cardiomyopathy Definition Dilated cardiomyopathy is a heart condition characterized by an enlarged left ventricle and systolic dysfunction in the absence of coronary artery disease or other structural heart disease. Incidence or prevalence The best estimates of prevalence range from 1/250 to 1/1700.1 However, large scale studies have failed to determine accurate incidence or prevalence data given that DCM is likely underdiagnosed. © 2020 eviCore healthcare. All Rights Reserved. 1 of 10 400 Buckwalter Place Boulevard, Bluffton, SC 29910 (800) 918-8924 www.eviCore.com Lab Management Guidelines V1.0.2020 Symptoms Average age of onset of DCM is in the 40s, but onset can begin as early as childhood. Enlargement of the left ventricle causes a weakened contraction of the heart muscle which in turn may lead to arrhythmias, -

Impact of Pericardial Effusion on Cardiac Mechanics in Patients with Dilated Cardiomyopathy

Impact of Pericardial Effusion on Cardiac Mechanics in Patients with Dilated Cardiomyopathy Francesco Scardulla1, Antonino Rinaudo1, Cesare Scardulla2 and Salvatore Pasta3 1Dipartimento di Ingegneria Chimica, Gestionale, Informatica e Meccanica, Universita' di Palermo, Viale delle Scienze Ed. 8, 90128 Palermo, Italy 2Mediterranean Institute for Transplantation and Advanced Specialized Therapies (ISMETT), Via Tricomi n.1, 90127, Palermo, Italy 3Fondazione RiMED, Via Bandiera n.11, 90133, Palermo, Italy Keywords: Finite Element Analysis, Cardiac Mechanics, Cardiomyopathy, Pericardial Effusion. Abstract: Dilated cardiomyopathy (CDM) is a degenerative disease of the myocardium accompanied by left ventricular (LV) remodeling, resulting in an impaired pump performance. Differently, pericardial effusion (PE) is a liquid accumulation in the pericardial cavity, which may inhibit blood filling of heart chambers. Clinical evidence show that PE may improve pump performance in patients with CDM. Therefore, this study aims to assess wall stress and global function of patients with CDM, PE as compared to healthy patient. These findings suggests that CDM has an important implication in the mechanical changes of LV and right ventricle by increasing wall stress and reducing pump function. Conversely, PE determines lowering myocardial fiber stress and improves global function as compared to those of CDM. 1 INTRODUCTION after surgery or can be secondary to congestive, severe heart failure. However, the mechanism of PE Dilated cardiomyopathy (CDM) is a degenerative development and its prognostic value in heart disease of the myocardial tissue accompanied by left failure remain elusive. A persistent PE at ventricular (LV) remodeling (Nakayama et al., echocardiographic follow-up was associated with 1987). The histologic characteristics of CDM unfavourable outcome when compared with patients include hypertrophy of myofibers, myofibrillar lysis, with resolved PE. -

Dilated Cardiomyopathy

Dilated Cardiomyopathy From Genetics to Clinical Management Gianfranco Sinagra Marco Merlo Bruno Pinamonti Editors Dilated Cardiomyopathy Gianfranco Sinagra • Marco Merlo Bruno Pinamonti Editors Dilated Cardiomyopathy From Genetics to Clinical Management Editors Gianfranco Sinagra Marco Merlo Cardiovascular Department Cardiovascular Department Azienda Sanitaria Universitaria Integrata Azienda Sanitaria Universitaria Integrata Trieste Trieste Italy Italy Bruno Pinamonti Cardiovascular Department Azienda Sanitaria Universitaria Integrata Trieste Italy ISBN 978-3-030-13863-9 ISBN 978-3-030-13864-6 (eBook) https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-13864-6 © The Editor(s) (if applicable) and The Author(s) 2019 This book is an open access publication Open Access This book is licensed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this book are included in the book’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the book’s Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. The use of general descriptive names, registered names, trademarks, service marks, etc. in this publication does not imply, even in the absence of a specific statement, that such names are exempt from the relevant protective laws and regulations and therefore free for general use. -

Genetic Testing for Hereditary Cardiomyopathies and Arrhythmias

Medical Coverage Policy Effective Date ............................................11/15/2020 Next Review Date ......................................11/15/2021 Coverage Policy Number .................................. 0517 Genetic Testing for Hereditary Cardiomyopathies and Arrhythmias Table of Contents Related Coverage Resources Coverage Policy ...................................................... 1 Genetics General Genetic Testing Criteria-Requirement for Implantable Cardioverter Defibrillator (ICD) Genetic Counseling ............................................... 2 Wearable Cardioverter Defibrillator and Confirmatory (Diagnostic) Genetic Testing ........... 2 Automatic External Defibrillator Dilated Cardiomyopathy (DCM) ............................ 3 Long QT Syndrome ............................................... 3 Known Familial Variant Mutation Analysis ............ 4 Other Genetic Testing Services ............................ 4 Overview .................................................................. 1 General Background .............................................. 5 Genetic Counseling ............................................... 5 Genetic Testing ..................................................... 5 Confirmatory (Diagnostic) Genetic Testing ........... 5 Dilated Cardiomyopathy (DCM) ............................ 6 Long QT Syndrome (LQTS) .................................. 6 Known Familial Variant Analysis ........................... 7 Other Genetic Testing Services ............................ 8 Appendix A ............................................................. -

Familial Long QT Syndrome and Late Development of Dilated Cardiomyopathy in a Child with a KCNQ1 Mutation: a Case Report

Familial long QT syndrome and late development of dilated cardiomyopathy in a child with a KCNQ1 mutation: A case report Kiona Y. Allen, MD, Victoria L. Vetter, MD, MPH, Maully J. Shah, MBBS, Matthew J. O’Connor, MD From the Division of Cardiology, The Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania. Introduction and nadolol thereafter. Throughout this time he was clin- Congenital long QT syndrome (LQTS) is an inherited ically well, without palpitations, syncope, or documented cardiac channelopathy characterized by prolongation of the arrhythmias, although his QTc remained prolonged on serial QT interval on electrocardiogram (ECG), and is associated ECG evaluations. He underwent formal exercise testing at 7 with an increased risk of life-threatening ventricular arrhyth- years of age, which was notable for a prolonged QTc mias. Mutations in over a dozen distinct genes have been throughout exercise and recovery. There were no arrhyth- implicated in the pathogenesis of this group of disorders.1 mias and he had a normal oxygen consumption of 40.5 mL/ LQTS type 1 (LQT1), the most prevalent LQTS subtype, is kg/min. He was active in multiple recreational sports, including basketball, lacrosse, and baseball; an automated characterized by a heterozygous loss-of-function mutation in fi the KCNQ1 gene, which codes for the α-subunit of the external de brillator was available for emergency use. delayed rectifier inward potassium ion channel. The associ- Repeat exercise testing was performed at 8 years of age, ation of LQTS with dilated cardiomyopathy (DCM) is rare which again demonstrated a prolonged QTc without ven- but has been reported in the presence of sodium channel gene tricular ectopy.