Proverbs and Worldviews: an Analysis of Ikwo Proverbs and Their Worldviews

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Nigeria Conflict Re-Interview (Emergency Response

This PDF generated by kmcgee, 8/18/2017 11:01:05 AM Sections: 11, Sub-sections: 0, Questionnaire created by akuffoamankwah, 8/2/2017 7:42:50 PM Questions: 130. Last modified by kmcgee, 8/18/2017 3:00:07 PM Questions with enabling conditions: 81 Questions with validation conditions: 14 Shared with: Rosters: 3 asharma (never edited) Variables: 0 asharma (never edited) menaalf (never edited) favour (never edited) l2nguyen (last edited 8/9/2017 8:12:28 PM) heidikaila (never edited) Nigeria Conflict Re- interview (Emergency Response Qx) [A] COVER No sub-sections, No rosters, Questions: 18, Static texts: 1. [1] DISPLACEMENT No sub-sections, No rosters, Questions: 6. [2] HOUSEHOLD ROSTER - BASIC INFORMATION No sub-sections, Rosters: 1, Questions: 14, Static texts: 1. [3] EDUCATION No sub-sections, Rosters: 1, Questions: 3. [4] MAIN INCOME SOURCE FOR HOUSEHOLD No sub-sections, No rosters, Questions: 14, Static texts: 1. [5] MAIN EMPLOYMENT OF HOUSEHOLD No sub-sections, No rosters, Questions: 6, Static texts: 1. [6] ASSETS No sub-sections, Rosters: 1, Questions: 12, Static texts: 1. [7] FOOD AND MARKET ACCESS No sub-sections, No rosters, Questions: 21. [8] VULNERABILITY MEASURE: COPING STRATEGIES INDEX No sub-sections, No rosters, Questions: 6. [9] WATER ACCESS AND QUALITY No sub-sections, No rosters, Questions: 22. [10] INTERVIEW RESULT No sub-sections, No rosters, Questions: 8, Static texts: 1. APPENDIX A — VALIDATION CONDITIONS AND MESSAGES APPENDIX B — OPTIONS LEGEND 1 / 24 [A] COVER Household ID (hhid) NUMERIC: INTEGER hhid SCOPE: IDENTIFYING -

The Socio-Cultural Implications of African Music Ferris (338) Observes: African Music and Dance

THE SOCIO-CULTURAL IMPLICATIONS Onwuekwe, Agatha Ijeoma, PhD OF AFRICAN MUSIC AND DANCE Dance is a very important aspect of African music as can be seen in the close relationship between body movement and music. Onwuekwe, Agatha Ijeoma, PhD In the dance arena it is natural for performers and listeners to move Music Department, Nnamdi Azikiwe University rhythmically. Drummers may move among dancers on the dance Awka ground, and in general, musical performance draws all people present into a unified atmosphere of action. Writing on dance, Okafor (5) submits: Abstract The dance is an ubiquitous medium of communication Music is as old as man himself. The origin of music can be or expression in African cultures. By its nature, a looked for in natural phenomena like the songs of the birds, the Nigerian dance or music engages all the senses in whirl of the wind, the roll of thunder, the prattling of the rain and performer and spectator/listener alike. It is the the crackling of fire. Through the imitation of these natural patterning of the human body in time and space in phenomena, man came about his music ages ago. Dance on the order to give expression to ideas and emotions. other hand is patterned and rhythmic body movements, usually performed to music or percussion. Dance is the transformation of African Music ordinary functional and expressive movement into extraordinary African music is that music indigenous to Africa. The music movement for extraordinary purposes. Each culture tends to have involves the language, the customs and values of the society. African its own distinctive styles of dance and reasons for dancing. -

2013 Federal Capital Budget Pull for South East

2013 FEDERAL CAPITAL BUDGET Of the States in the SOUTH EAST Geo-Political Zone Citizens Wealth Platform (CWP) (Public Resources Are Made To Work And Be Of Benefit To All) 2013 FEDERAL CAPITAL BUDGET of the States in the South East Geo-Political Zone Citizens Wealth Platform (CWP) (Public Resources Are Made To Work And Be Of Benefit To All) ii 2013 FEDERAL CAPITAL BUDGET of the States in the South East Geo-Political Zone Compiled by ……………………… For Citizens Wealth Platform (CWP) (Public Resources Are Made To Work And Be Of Benefit To All) iii First Published in September 2013 By Citizens Wealth Platform C/o Centre for Social Justice 17 Yaounde Street, Wuse Zone 6, Abuja Email: [email protected] iv Table of Contents Acknowledgment vi Foreword vii Abia State 1 Anambra State 16 Ebonyi State 25 Enugu State 29 Imo State 42 v Acknowledgment Citizens Wealth Platform acknowledges the financial and secretariat support of Centre for Social Justice towards the publication of this Capital Budget Pull-Out. vi Foreword This is the second year of the publication of Capital Budget Pull-outs for the six geo-political zones. Citizens Wealth Platform (CWP) is setting the agenda of public participation in fiscal governance especially in monitoring and tracking capital budget implementation. Popular and targeted participation is essential to hold government accountable to the promises made in the annual budget particularly the aspects of the budget that touch on the lives of the common people. In 2013, the Federal Government of Nigeria (FGN) promised to build roads, bridges, hospitals, renovate airports and generally take actions to improve living standards. -

Rice Production and Food Security in Nigeria: a Synoptic History of the Ikwo Brand

International Journal of Advanced Academic Research | Arts, Humanities & Education | ISSN: 2488-9849 Vol. 3, Issue 4 (April 2017) Rice Production And Food Security In Nigeria: A Synoptic History Of The Ikwo Brand Kelechi J. Ani, Ph.D (In view) Department of History and Strategic Studies, Federal University Ndufu-Alike, Ikwo, Ebonyi State, Nigeria. [email protected] Gift Maxwell, B. A. (Hons.) Alumnus, Department of History and Strategic Studies, Federal University Ndufu-Alike, Ikwo, Ebonyi State, Nigeria. [email protected] Chinyere S. Ecoma, Ph.D (Corresponding Author) Department of History and International Relations, Veritas University, Abuja, Nigeria. [email protected] ABSTRACT Rice is a fundamental edible crop that is widely cultivated in different parts of Nigeria. It is a major source of carbohydrate. It is widely consumed by the rich and the poor in the country. This study presents a synoptic history of Ikwo people and their rice production experiences. It highlights the types of rice planted in the area and the changing patterns of rice production amongst the people. The study documents the role of Norwegian Church Agricultural Project (NORCAP) in promoting rice production in the clan. It also examines the challenges confronting rice production in Ikwo. The evolution of rice de-stoning, bagging of rice and change from the production of short species of rice to long species were also discussed in the study. Such problems as poverty, environmental dependency, especially on rainfall and lack of technical know-how were highlighted as challenges militating against the rise of a robust farming culture. The study recommends mechanised agriculture, adoption of modern irrigation strategies, agricultural seminars and workshops by agricultural extension as a way of improving food security in Nigeria. -

National Assembly 260 2013 Appropriation

FEDERAL GOVERNMENT OF NIGERIA 2013 BUDGET SUMMARY FEDERAL MINISTRY OF WATER RESOURCES TOTAL TOTAL PERSONNEL TOTAL CODE MDA OVERHEAD TOTAL RECURRENT TOTAL CAPITAL COST ALLOCATION COST =N= =N= =N= =N= =N= FEDERAL MINISTRY OF WATER RESOURCES - 0252001001 1,062,802,556 434,615,687 1,497,418,243 28,714,910,815 30,212,329,058 HQTRS 0252037001 ANAMBRA/ IMO RBDA 455,494,870 69,652,538 525,147,408 7,223,377,629 7,748,525,037 252038001 BENIN/ OWENA RBDA 310,381,573 48,517,004 358,898,577 2,148,547,575 2,507,446,152 0252039001 CHAD BASIN RBDA 349,481,944 66,930,198 416,412,142 2,090,796,556 2,507,208,698 0252040001 CROSS RIVER RBDA 336,692,834 69,271,822 405,964,656 5,949,000,000 6,354,964,656 0252051001 GURARA WATER MANAGEMENT AUTHORITY 17,112,226 70,346,852 87,459,078 167,000,000 254,459,078 0252041001 HADEJIA-JAMAļARE RBDA 384,683,182 53,037,247 437,720,429 5,322,607,552 5,760,327,981 0252042001 LOWER BENUE RBDA 305,996,666 49,183,926 355,180,592 4,684,200,000 5,039,380,592 0252043001 LOWER NIGER RBDA 510,037,910 66,419,289 576,457,199 5,452,950,000 6,029,407,199 0252044001 NIGER DELTA RBDA 509,334,321 77,714,503 587,048,824 4,382,640,000 4,969,688,824 NIGERIA INTEGRATED WATER MANAGEMENT 0252050001 143,297,122 89,122,355 232,419,477 154,000,000 386,419,477 COMMISSION NATIONAL WATER RESOURCES INSTITUTE- 0252049001 266,646,342 40,532,007 307,178,349 403,000,000 710,178,349 KADUNA 0252045001 OGUN/ OSUN RBDA 387,437,686 79,556,978 466,994,664 3,500,153,045 3,967,147,709 0252046001 SOKOTO RIMA RBDA 431,782,730 83,609,292 515,392,022 6,827,983,001 7,343,375,023 -

O Rigin Al a Rticle

International Journal of History and Research (IJHR) ISSN(P): 2249–6963; ISSN(E): 2249–8079 Vol. 10 Issue 2, Dec 2020, 1–12 ©TJPRC Pvt. Ltd AFIKPO-ABAKALIKI RELATIONS: TRACING THE ROOTS DR. FRANCIS C. ODEKE & DR. IKECHUKWU O. ONUOHA Department of History and International Relations, Faculty of Social Sciences and Humanities, Ebonyi State University, Abakaliki ABSTRACT There has been a serious controversy over the origin of Afikpo and Abakaliki people of Ebonyi State, Nigeria. The argument borders on whether the two groups had shared a common origin before they parted ways as a result of wars and other factors in their early histories. This paper is a comparative study of the two cultural groups. It intends to examine their similar and dissimilar traits with a view to unearthing their common grounds in the early times of their history. The study uses both the primary and secondary sources of data. A thematic study, the paper adopts the analytic and narrative approaches of history as its methodology. The paper finds facts in some deities bearing the same name in both clans, initiations rites that serve the same purpose among the groups, same belief systems, some common customs and norms, veneration methods for social violations, and many other common traits in the lives of the two groups, as proofs that the people had had many things in common in their early history. With these findings, the paper holds that Afikpo andAbakaliki people migrated from same place,and later settled together for some centuries at a commonlocation Article Original where they evolved some of their cultures before wars and other exigencies of the environment scattered them to new settlements. -

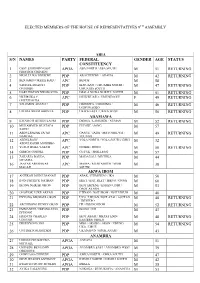

List of the Elected House of Representatives Members for the 9Th Assembly

ELECTED MEMBERS OF THE HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES 9TH ASSEMBLY ABIA S/N NAMES PARTY FEDERAL GENDER AGE STATUS CONSTITUENCY 1 OSSY EHIRIODO OSSY APGA ABA NORTH / ABA SOUTH M 51 RETURNING PRESTIGE CHINEDU 2 NKOLE UKO NDUKWE PDP AROCHUKWU / OHAFIA M 42 RETURNING 3 BENJAMIN OKEZIE KALU APC BENDE M 58 4 SAMUEL IFEANYI PDP IKWUANO / UMUAHIA NORTH / M 47 RETURNING ONUIGBO UMUAHIA SOUTH 5 DARLINGTON NWOKOCHA PDP ISIALA NGWA NORTH / SOUTH M 51 RETURNING 6 NKEIRUKA C. APC ISUIKWUATO / UMUNEOCHI F 49 RETURNING ONYEJEOCHA 7 SOLOMON ADAELU PDP OBINGWA / OSISIOMA / M 46 RETURNING UGWUNAGBO 8 UZOMA NKEM ABONTA PDP UKWA EAST / UKWA WEST M 56 RETURNING ADAMAWA 9 KWAMOTI BITRUS LAORI PDP DEMSA / LAMURDE / NUMAN M 52 RETURNING 10 MUHAMMED MUSTAFA PDP FUFORE / SONG M 57 SAIDU 11 ABDULRAZAK SA’AD APC GANYE / JADA / MAYO BELWA / M 49 RETURNING NAMDAS TOUNGO 12 ABDULRAUF APC YOLA NORTH / YOLA SOUTH/ GIREI M 32 ABDULKADIR MODIBBO 13 YUSUF BUBA YAKUB APC GOMBI / HONG M 50 RETURNING 14 GIBEON GOROKI PDP GUYUK / SHELLENG M 57 15 ZAKARIA DAUDA PDP MADAGALI / MICHIKA M 44 NYAMPA 16 JAAFAR ABUBAKAR APC MAIHA / MUBI NORTH / MUBI M 38 MAGAJI SOUTH AKWA IBOM 17 ANIEKAN JOHN UMANAH PDP ABAK / ETIM EKPO / IKA M 50 18 IFON PATRICK NATHAN PDP EKET / ESIT EKET / IBENO / ONNA M 60 19 IKONG NSIKAK OKON PDP IKOT EKPENE / ESSIEN UDIM / M 53 OBOT AKARA 20 ONOFIOK LUKE AKPAN PDP ETINAN / NSIT IBOM / NSIT UBIUM M 40 21 ENYONG MICHAEL OKON PDP UYO / URUAN /NSIT ATAI / ASUTAN M 48 RETURNING / IBESIKPO 22 ARCHIBONG HENRY OKON PDP ITU /IBIONO IBOM M 52 RETURNING 23 EMMANUEL UKPONG-UDO -

Migration Wars in the Traditional Igbo Society and the Challenges of National Security: the Abakaliki Experience, 1800-1920

International and Public Affairs 2019; 3(1): 25-32 http://www.sciencepublishinggroup.com/j/ipa doi: 10.11648/j.ipa.20190301.15 ISSN: 2640-4184 (Print); ISSN: 2640-4192 (Online) Migration Wars in the Traditional Igbo Society and the Challenges of National Security: The Abakaliki Experience, 1800-1920 Amiara Solomon Amiara Department of History and International Relations, Faculty of Social Sciences and Humanities, Ebonyi State University, Abakaliki, Nigeria Email address: To cite this article: Amiara Solomon Amiara. Migration Wars in the Traditional Igbo Society and the Challenges of National Security: The Abakaliki Experience, 1800-1920. International and Public Affairs . Vol. 3, No. 1, 2019, pp. 25-32. doi: 10.11648/j.ipa.20190301.15 Received : December 12, 2018; Accepted : January 2, 2019; Published : August 12, 2019 Abstract: Traditionally, state formation was characterized with wars of different magnitude. The nature, types and causes of the war differed from one state to another. The Igbo nation was one of those areas that witnessed migratory wars arising from state formation, land dispute, slave raiding and boundary crises. Considering the fact that the Igbo history of origin underpins diverse integrations and accounts, one can say that some Igbo sub-groups at different times, fought different wars with one another in search of national homeland. The outcome of these wars underscores the migration and settlement that predated the Igbo nation before the 18 th century wars, particularly the Ezza that are scattered all over Nigeria. The continuous movement of these people and many other Igbo sub-groups has led to the intermittent wars that characterized Nigerian state. -

List of 2021 Abstracts

&&&&&&&&&&&&&&&&&&&&&&&&&&&&&&&&&&&&&&&&&&&&&&&&&& ABSTRACTS 2021 VIRTUAL IGBO STUDIES ASSOCIATION INTERNATIONAL CONFERENCE &&&&&&&&&&&&&&&&&&&&&&&&&&&&&&&&&&&&&&&&&&&&&&&&&& A Aboekwe, Mary Emilia Nwanyi Bu Ihe: In the Light of the Igbo Social World Obielosi, Dominic Department of Religion and Human Relations, Nnamdi Azikiwe University, Awka, Anambra State, Nigeria Aboekwe, Mary Emilia Department of Religion and Society, Chukwuemeka Odumegwu Ojukwu University, Igbariam, Anambra State, Nigeria In traditional Igbo social setting, the male child is preferred to the female child. Igbo society is gender sensitive and patriarchal in nature. Even at birth, warm welcome, special recognition is accorded to the male child as against the female counterpart. The male child is perceived as a sustainer of lineage, holder of central and important positions of authority and inheritor of immovable pieces of property. Early in life, the male child is made to feel that he is superior to the female child. Thus, wives wish to give birth to male children as that will properly endear them to their husbands. Husbands are also joyous when their wives give birth to male children. This reassures them that they have someone to take their places after their death, to continue their family line. This paper argues that urbanization has drastically changed this pattern of life. In contemporary society, female children take better and more appropriate care of their parents than the male children. Parents prefer and feel comfortable spending holidays in their daughters’ home than in their male children’s homes. This paper, therefore, draws attention to the changed social situation and the increasing value that is accruing to the girl- child. Key words: Female, male, patriarchy. -

Nigeria Security Situation

Nigeria Security situation Country of Origin Information Report June 2021 More information on the European Union is available on the Internet (http://europa.eu) PDF ISBN978-92-9465-082-5 doi: 10.2847/433197 BZ-08-21-089-EN-N © European Asylum Support Office, 2021 Reproduction is authorised provided the source is acknowledged. For any use or reproduction of photos or other material that is not under the EASO copyright, permission must be sought directly from the copyright holders. Cover photo@ EU Civil Protection and Humanitarian Aid - Left with nothing: Boko Haram's displaced @ EU/ECHO/Isabel Coello (CC BY-NC-ND 2.0), 16 June 2015 ‘Families staying in the back of this church in Yola are from Michika, Madagali and Gwosa, some of the areas worst hit by Boko Haram attacks in Adamawa and Borno states. Living conditions for them are extremely harsh. They have received the most basic emergency assistance, provided by our partner International Rescue Committee (IRC) with EU funds. “We got mattresses, blankets, kitchen pots, tarpaulins…” they said.’ Country of origin information report | Nigeria: Security situation Acknowledgements EASO would like to acknowledge Stephanie Huber, Founder and Director of the Asylum Research Centre (ARC) as the co-drafter of this report. The following departments and organisations have reviewed the report together with EASO: The Netherlands, Ministry of Justice and Security, Office for Country Information and Language Analysis Austria, Federal Office for Immigration and Asylum, Country of Origin Information Department (B/III), Africa Desk Austrian Centre for Country of Origin and Asylum Research and Documentation (ACCORD) It must be noted that the drafting and review carried out by the mentioned departments, experts or organisations contributes to the overall quality of the report, but does not necessarily imply their formal endorsement of the final report, which is the full responsibility of EASO. -

Dynamics of Pre-Colonial Diplomatic Practices Among the Igbo Speaking People of Southeastern Nigeria, 1800-1900: a Historical Evaluation

Historical Research Letter www.iiste.org ISSN 2224-3178 (Paper) ISSN 2225-0964 (Online) Vol.43, 2017 DYNAMICS OF PRE-COLONIAL DIPLOMATIC PRACTICES AMONG THE IGBO SPEAKING PEOPLE OF SOUTHEASTERN NIGERIA, 1800-1900: A HISTORICAL EVALUATION Patrick Okpalaeke Chukwudike 1 Esin Okon Eminue 2 1. Department of History and International Studies, University of Uyo, Uyo. Nigeria 2. Department of History and International Studies, University of Uyo, Uyo, Nigeria E-mail: [email protected] Abstract This paper seeks to conduct a historical evaluation on the dynamics of pre-colonial diplomatic relations among the Igbo speaking people of Southeastern Nigerian. This became a necessity owing to the fact that there appear to be a big neglect by scholars of Igbo descent in discussing the mode by which city-states littered across the Southeastern region of Nigeria conducted their own unique form of diplomacy. This implication of this neglect have only given further credence to Eurocentric claims that “Africa has no history”. It is a historical fact that when most societies where invaded by European colonialists, they paid little or no attention to how these societies have conducted indigenous affairs that have for centuries sustained them. Rather, a conclusion was drawn that these pre-colonial societies were devoid of any meaningful aspect of life that should be understudied. Be that as it may, through the concept of African historiography, the fore-going has long been debunked with the help of oral history as enunciated by Jan Vasina. However, what is yet to receive adequate attention is the art of diplomacy across Africa, vis a vis the conduct of diplomatic practices among the Igbo speaking people of Southeast Nigeria .Thus, the study reveals base on the much available sources, that in pre-colonial Igboland, the people conducted a unique and sophisticated art of diplomacy. -

Fifth Edition South East EBONYI

STATES IN NIGERIA- PROFILE EBONYI, AKWA IBOM, ONDO, NIGER STATE, BORNO, KATSINA Fifth edition South East EBONYI South South AKWA IBOM South West ONDO North Central NIGER STATE North East BORNO North West KATSINA EBONYI STATE IGR (2017): 5.10 FAAC (2017)(bn): 35.49 GDP(2015)($bn): 6.08 Budget(2018)(Nbn): 208.30 Population(2006): 2,176,947 Unemployment(2011): 25.1 % Literacy Rate(2010): 70.0% Area: 5,533 km2 (2,136 sq mi) Density: 390/km2 (1,000/sq mi) EBONYI STATE BACKGROUND ECONOMY Ebonyi State, a state located in the South-East geopolitical zone Industrial sector, Ebonyi has dozens of rice mills, many quarry of Nigeria was created on 1 October 1996. The state capital is factories, a fertilizer blending plant, one of Nigeria’s largest Abakaliki which is also the largest city in the state. poultries (Nkali Poultry) and one of Nigeria’s foremost cement LGA: Ebonyi has 13 Local Government Area’s namely Abakaliki, factories (the Nigerian Cement Company at Nkalagu). Afikpo North, Afikpo South, Ebonyi, Ezza North, Ezza Agriculture: The people are predominantly farmers and traders. South, Ikwo, Ishielu, Ivo, Izzi, Ohaozara, Ohaukwu, Onicha. Major farm produce in the state include; rice, yam, palm produce. Ethnicity: Ebonyi people are predominantly of Igbo ethnicity. The Cocoa, maize, groundnut, plantain, banana, cassava, melon, sugar native language is Igbo, However, English is widely spoken and cane, beans, fruits, vegetables, rice and yams are predominantly serves as the states official language. cultivated in Edda, a region within the state and Fishing is carried Motto: Ebonyi State’s motto is “Salt of the Nation”.