Report on Mapping Livelihoods and Nutrition in Nigeria

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Biodiversity Conservation Friendliness Status of Rural Farmers in Abak Agricultural Zone of Akwa Ibom State

International Journal of Environment and Climate Change 10(9): 179-189, 2020; Article no.IJECC.59232 ISSN: 2581-8627 (Past name: British Journal of Environment & Climate Change, Past ISSN: 2231–4784) Biodiversity Conservation Friendliness Status of Rural Farmers in Abak Agricultural Zone of Akwa Ibom State J. T. Ekanem1*, N. U. Okorie1 and J. Ibanga1 1Department of Agricultural Economics and Extension, Akwa Ibom State University, Obio Akpa, Campus, P.M.B. 1167, Uyo, Akwa Ibom State, Nigeria. Authors’ contributions This work was carried out in collaboration among all authors. Author JTE designed the study, performed the statistical analysis and wrote the protocol. Author JI wrote the first draft of the manuscript. Authors JTE and JI managed the analyses of the study. Author NUO managed the literature searches. All authors read and approved the final manuscript. Article Information DOI: 10.9734/IJECC/2020/v10i930239 Editor(s): (1) Dr. Anthony R. Lupo, University of Missouri, USA. (2) Dr. Hani Rezgallah Al-Hamed Al-Amoush, Al al-Bayt University, Jordan. (3) Dr. Wen-Cheng Liu, National United University, Taiwan. Reviewers: (1) Madhulika Sahoo, Vellore Institute of Technology, School of Business, India. (2) Bulbul G. Nagrale, Maharashtra Animal & Fishery Sciences University, India. (3) Aditya Pratap Singh, Bidhan Chandra Krishi Viswavidyalaya (BCKV), India. Complete Peer review History: http://www.sdiarticle4.com/review-history/59232 Received 14 June 2020 Original Research Article Accepted 19 August 2020 Published 28 August 2020 ABSTRACT Consolidating on farmers’ agro-ecological knowledge to design environmental-friendly agricultural systems is crucial given the environmental impact of commercial agriculture. The study aimed at assessing the awareness level of the respondents on biodiversity conservation, their biodiversity conservation information source(s), respondents’ information seeking behaviour and their perception towards biodiversity conservation. -

Flood Vulnerability Assessment of Afikpo South Local Government Area, Ebonyi State, Nigeria

International Journal of Environment and Climate Change 9(6): 331-342, 2019; Article no.IJECC.2019.026 ISSN: 2581-8627 (Past name: British Journal of Environment & Climate Change, Past ISSN: 2231–4784) Flood Vulnerability Assessment of Afikpo South Local Government Area, Ebonyi State, Nigeria Endurance Okonufua1*, Olabanji O. Olajire2 and Vincent N. Ojeh3 1Department of Road Research, Nigerian Building and Road Research Institute, Ota, Ogun State, Nigeria. 2African Regional Centre for Space Science and Technology Education in English, OAU and Centre for Space Research and Applications, Federal University of Technology, Akure, Nigeria. 3Department of Geography, Taraba State University, P.M.B. 1167, Jalingo, Nigeria. Authors’ contributions This work was carried out in collaboration among all authors. Authors EO, OOO and VNO designed the study, performed the statistical analysis, wrote the protocol and wrote the first draft of the manuscript. Authors OOO and VNO managed the analyses of the study. Author EO managed the literature searches. All authors read and approved the final manuscript. Article Information DOI: 10.9734/IJECC/2019/v9i630118 Editor(s): (1) Dr. Anthony R. Lupo, Professor, Department of Soil, Environmental and Atmospheric Science, University of Missouri, Columbia, USA. Reviewers: (1) Ionac Nicoleta, University of Bucharest, Romania. (2) Neha Bansal, Mumbai University, India. (3) Abdul Hamid Mar Iman, Universiti Malaysia Kelantan, Malaysia. Complete Peer review History: http://www.sdiarticle3.com/review-history/48742 Received 26 March 2019 Accepted 11 June 2019 Original Research Article Published 18 June 2019 ABSTRACT The study was conducted in Afikpo South Local Government covering a total area of 331.5km2. Remote sensing and Geographic Information System (GIS) were integrated with multicriteria analysis to delineate the flood vulnerable areas. -

4 YEARS Plus of GOV UDOM EMMANUEL.Cdr

F AK O WA T N IB E O M M N S R T E A V T O E G 4 YEARS TOUCHING LIVES May 2015 Job Creation 2016 Infrastructural Consolidation & Expansion 2017 Poverty Alleviation 2018 Economic & Political N Inclusion Wealth Creation May 2019 The Five-Point Agenda of Governor Udom Emmanuel AVIATION May 2019 INDUSTRIALIZATION DEVELOPMENT SMALL & RURAL & 2020 MEDIUM SCALE RIVERINE AREA ENTERPRISES DEVELOPMENT The next COMPLETION four 2021 years AGENDA INFRASTRUCTURE AGRICULTURE 2022 May 2023 SECURITY HUMAN CAPACITY DEVELOPMENT 02 www.akwaibomstate.gov.ng TOUCHING LIVES IN MORE WAYS ... n 11,000 hectares of coconut plantation n Over 1700km of roads n 3,240 hectares of cassava plantation in 15 LGAs (FADAMA) n 40 bridges n 49,318 registered rice farmers n Completion of the State Secretariat Annex n 450 youths trained on cocoa maintenance n Construction of 2nd airport runway (taxiway) n Subsidized fertilizers, oil palm & cocoa seedlings n Upgrade of Airport main runway to category 2 n Akwa Prime Hatchery -17,000 day old chicks weekly n Only state to own & maintain an airport independently n Free Improved Corn seedlings n n Flood control at Nsikak Eduok n Vegetable Green Houses Completion of Four Points by Sheraton Hotel n n International Worship Centre (on-going) Avenue, Uyo Roads & Oil Palm Processing Plant n n n Eket International Modern Market 21 Storey Intelligent office Agriculture Cassava Processing Mills n Airport Terminal building (under construction) complex...ongoing n Maize Shelling/Drying Mill Other Infrastructure n n Renovation of 85 Flats at n Rice Processing Mills Expansion of Shopping Mall at Ibom Wellington Bassey Army Barracks, n Over 1,200 hectares of rice cultivated Tropicana Entertainment Centre n Ibagwa n N300,000 grant to 250 beneficiaries under the Graduate Unemployment Completion of Governor’s Lodge, Lagos n Private Hangar for State aircraft Youth Scheme n Setting up of Ibom FADAMA Micro Finance Bank n Free medical services for children below 5 years, n Free & compulsory basic education in public schools pregnant women & the aged. -

Analysis of Spring Water Quality in Ebonyi South Zone and Its Health Impact 1J.N

AMERICAN JOURNAL OF SCIENTIFIC AND INDUSTRIAL RESEARCH © 2013, Science Huβ, http://www.scihub.org/AJSIR ISSN: 2153-649X, doi:10.5251/ajsir.2013.4.2.231.237 Analysis of spring water quality in Ebonyi South Zone and its health impact 1J.N. Afiukwa and 2A.N. Eboatu 1Department of Industrial Chemistry, Ebonyi State University Private Mail Bag 053, Abakaliki, Nigeria 2Department of Pure and Industrial Chemistry, Nnamdi Azikiwe University, Awka, Anambra State, Nigeria. ABSTRACT Studies were carried out between June through December, 2007 to evaluate the quality of rural water supply for drinking in Ebonyi South Zone of Ebonyi State, Nigeria. The rural communities of Ekoli Edda and Ozizza in Afikpo South L.G.A and parts of Okposi in Ohaozara L.G.A depend solely on spring water for their domestic needs. Samples from seven spring water sources in these areas were analyzed for some physico-chemical and microbial parameters by standard methods. Concentrations of some heavy metals; Cr, Cd, Co, Cu, Fe, Mn, Pb, Ni and Zn were determined using Atomic Absorption Spectrophotometer. The results of the chemical analysis compared favourably with the WHO standard for drinking water, except for the relatively high concentration of iron in samples SE 5 (0.79 mg/L) and SE 6 (0.58 mg/L), and the exceedingly high phosphate concentrations, ranging from 0.25 - 1.6mg/L in all the samples as against the WHO permissible limit of 0.1mg/L. The bacteriological analyses however revealed about 40% total coliform bacteria contamination, varying between 0 - 4 MPN/100 ml of water in five out of the seven samples tested. -

World Bank Document

ESMP for Nguzu Edda (Afikpo South LGA Headquarters) Gully Erosion site in Ebonyi State Public Disclosure Authorized ENVIRONMENTAL AND SOCIAL MANAGEMENT PLAN (ESMP) (Final Draft Report) For NGUZU EDDA (AFIKPO SOUTH LOCAL GOVERNMENT HEADQUARTERS) GULLY EROSION INTERVENTION SITE, EBONYI STATE Public Disclosure Authorized UNDER Public Disclosure Authorized THE NIGERIA EROSION & WATERSHED MANAGEMENT PROJECT (NEWMAP) WORLD BANK ASSISTED By EBONYI STATE -NIGERIA EROSION & WATERSHED MANAGEMENT PROJECT (EBS-NEWMAP) ABAKALIKI, EBONYI STATE Public Disclosure Authorized Public Disclosure Authorized June, 2014 ESMP for Nguzu Edda (Afikpo South LGA Headquarters) Gully Erosion site in Ebonyi State ESMP for Nguzu Edda (Afikpo South LGA Headquarters) Gully Erosion site in Ebonyi State Table of Contents Content Page Cover Page i Table of Contents ii List of Tables v List of Figures vi List of Maps vi List of Boxes vi List of Abbreviations/ Acronyms vii Definition of Terms ix Executive Summary x CHAPTER 1: GENERAL INTRODUCTION 1 1.1 Background 2 1.2 The proposed Intervention Work 3 1.3 Need for ESMP for the Proposed Intervention Work 4 1.4 Objectives of this Environmental and Social Management Plan 4 1.5 Scope/Terms of Reference of the ESMP and Tasks 4 1.6 Approaches for Preparing the Environmental and Social Management Plan 4 1.6.1 Literature Review 4 1.6.2 Interactive Discussions/Consultations 4 1.6.3 Field Visits 4 1.6.4 Identification of Potential Impacts and Mitigation Measures 4 CHAPTER 2: INSTITUTIONAL AND LEGAL FRAMEWORK FOR ENVIRONMENTAL MANAGEMENT -

Abia State No

ABIA STATE NO. NAME STATUS ADDRESS 1 ABIA FIRST II DRIVING SCHOOL APPROVED NO 140 UMULE RD. BY UKWUAKPU OSISIOMA ABA. 2 AJAE DRIVING SCHOOL APPROVED NO 53 AWOLOWO SGBY UMUWAYA ROAD UMUAHIA 3 BASIC DRIVING SCHOOL APPROVED OPPOSITE VISION AFRICA RADIO UMUAHIA 4 BENSON DRIVING SCHOOL APPROVED UBAKALA STREET BY CO-OPERATIVE UMUAHIA 5 BOBOS DRIVING SCHOOL APPROVED NO. 105 ABA OWEERI ROAD, ABIA STATE 6 CAREFUL DRIVING SCHOOL APPROVED 111/113 AZIKWE ROAD ABA 7 CHIBEST DRIVING SCHOOL APPROVED NO 7 INDUSTRIAL LAYOUT OSISIOMA NGWA LOCAL GOVT AREA 8 CHIBEST DRIVING SCHOOL UMUAHIA APPROVED 34A POWA SHOPPING PLAZA UMUAHIA, NORTH LGA, ABIA STATE 9 CHINEDUM PRIVATE DRIVING APPROVED NO 2 AZIKWE OCHENDU CLOSE 10 DIAMOND HEART INTERNATIONAL APPROVED NO.10 BCA ROAD UMUAHIA DRIVING SCHOOL 11 DIVINE DRIVING SCHOOL APPROVED AHIAEKE NDUME IBEKU OFF UMUSIKE ROAD UMUAHIA 12 DRIVE-WELL SCHOOL OF MOTORING, APPROVED 27 BRASS ST. ABA ABIA STATE. 13 ENG AMOSON DRIVING SCH APPROVED 95 FGC ROAD EBEM OHAFIA 14 EXPERTS DRIVING SCH APPROVED 133 IKOT- EKPENE ROAD OGBORHILL ABA, ABA NORTH LGA, ABIA STATE. 15 FLUX DRIVING SCHOOL APPROVED OPPOSITE VISION AFRICA F.M RADIO ALONG SECRETARIAT ROAD, OGURUBE LAYOUT UMUAHIA 16 GIVENCHY DRIVING SCHOOL APPROVED NO 60 WARRI BY BENDER ROAD UMUAHIA, ABIA STATE. 17 HALLMARK DRIVING SCHOOL APPROVED SUITE 4, 44-55 OSINULO SHOPPING COMPLEX ISI COURT UMUOBIA OLOKORO, UMUAHIA, ABIA STATE 18 IFEANYI DRIVING SCHOOL APPROVED AMAWOM OBORO IKWUANO LGA 19 IJEOMA DRIVING SCHOOL APPROVED NO.3 CHECHE CLOSE AMANGWU, OHAFIA, ABIA STATE 20 INTERNATIONAL DRIVING SCHOOL APPROVED NO. 2 MECHANIC LAYOUT OFF CLUB ROAD UMUAHIA. -

Citizens Wealth Platform 2017

2017 FEDERAL CAPITAL BUDGET PULLOUT Of the States in the SOUTH-EAST Geo-Political Zone C P W Citizens Wealth Platform Citizen Wealth Platform (CWP) (Public Resources Are Made To Work And Be Of Benefit To All) 2017 FEDERAL CAPITAL BUDGET of the States in the SOUTH EAST Geo-Political Zone Compiled by VICTOR EMEJUIWE For Citizens Wealth Platform (CWP) (Public Resources Are Made To Work And Be Of Benefit To All) 2017 SOUTH EAST FEDERAL CAPITAL BUDGET PULLOUT Page 2 First Published in August 2017 By Citizens Wealth Platform C/o Centre for Social Justice 17 Yaounde Street, Wuse Zone 6, Abuja Email: [email protected] Website: www.csj-ng.org Tel: 08055070909. Blog: csj-blog.org. Twitter:@censoj. Facebook: Centre for Social Justice, Nigeria 2017 SOUTH EAST FEDERAL CAPITAL BUDGET PULLOUT Page 3 Table of Contents Foreword 5 Abia State 6 Anambra State 26 Embonyi State 46 Enugu State 60 Imo State 82 2017 SOUTH EAST FEDERAL CAPITAL BUDGET PULLOUT Page 4 Foreword In the spirit of the mandate of the Citizens Wealth Platform to ensure that public resources are made to work and be of benefit to all, we present the South East Capital Budget Pullout for the financial year 2017. This has been our tradition in the last six years to provide capital budget information to all Nigerians. The pullout provides information on federal Ministries, Departments and Agencies, names of projects, amount allocated and their location. The Economic Recovery and Growth Plan (ERGP) is the Federal Government’s blueprint for the resuscitation of the economy and its revival from recession. -

Sustainability of the Niger State CDTI Project, Nigeria

l- World Health Organization African Programme for Onchocerciasis Control FINAL RËPOftî ,i ={ Evaluation of the Sustainability of the Niger State CDTI Project, Nigeria N ove m ber- Decem ber 2004 Elizabeth Elhassan (Team Leader) Uwem Ekpo Paul Kolo William Kisoka Abraraw Tefaye Hilary Adie f'Ï 'rt\ t- I I I TABLE OF CONTENTS I Table of contents............. ..........2 Abbreviations/Acronyms ................ ........ 3 Acknowledgements .................4 Executive Summary .................5 *? 1. lntroduction ...........8 2. Methodology .........9 2.1 Sampling ......9 2.2 Levels and lnstruments ..............10 2.3 Protocol ......10 2.4 Team Composition ........... ..........11 2.5 Advocacy Visits and 'Feedback/Planning' Meetings........ ..........12 2.6 Limitations ..................12 3. Major Findings And Recommendations ........ .................. 13 3.1 State Level .....13 3.2 Local Government Area Level ........21 3.3 Front Line Health Facility Level ......27 3.4 Community Level .............. .............32 4. Conclusions ..........36 4.1 Grading the Overall Sustainability of the Niger State CDTI project.................36 4.2 Grading the Project as a whole .......39 ANNEXES .................40 lnterviews ..............40 Schedule for the Evaluation and Advocacy.......... .................42 Feedback and Planning Meetings, Agenda.............. .............44 Report of the Feedbacl</Planning Meetings ..........48 Strengths And Weaknesses Of The Niger State Cdti Project .. .. ..... 52 Participants Attendance List .......57 Abbrevi -

Spatial Pattern of Housing Quality in Abuja, Nigeria

International Journal of Coal, Geology and Mining Research Vol.2, No.1, pp.1-20, May 2020 Published by European Centre for Research Training and Development UK(www.eajournals.org) SPATIAL PATTERN OF HOUSING QUALITY IN ABUJA, NIGERIA Saliman Dauda Department of Urban and Regional Planning, Baze University, Abuja, Nigeria ABSTRACT: The study attempted evaluation of Spatial Pattern of Housing Quality of Abuja, Nigeria. The identified 62 political wards were stratified into their various Area Councils namely, Abuja Municipal Area Council (AMAC), Bwari Area Council, Gwagwalada Area Council, KwaliArea Council, Kuje Area Council and Abaji Area Council. Using systematic random sampling, 3593, 1002,641,290,341 and 202 houses were selected in AMAC, Bwari Area Council, Gwagwalada Area Council, Kwali Area Council, Kuje Area Council and Abaji Area Council respectively to give a total of 6069 houses. Socioeconomic characteristics of the households revealed that the youth constituted 14.2% of the respondents, while 79.99% of the respondents were also found to be in the age bracket of 31-60 years. Analysis of Variance (ANOVA) confirmed, that there were significant differences in the age distribution of the residents (F = 4.11, p = 0.005). Analysis of spatial pattern of housing quality using Factor Analysis revealed that housing location quality attributes factor, recorded highest influence on the spatial pattern of housing quality in Area Councils, such as AMAC, Bwari Area Council and Gwagwalada Area Council. The study concluded that a general hierarchical trend in spatial pattern of housing quality had been figured out in Abuja, where housing quality was observed to decrease with increase in distance from the Central Business District(CBD). -

Frugivorous Bird Species Diversity in Relation to the Diversity of Fruit

ISBN: 2141 – 1778 jfewr ©2016 - jfewr Publications E-mail:[email protected] 80 FRUGIVOROUS BIRD SPECIES DIVERSITY IN RELATION TO THE DIVERSITY OF FRUIT TREE SPECIES IN RESERVED AND DESIGNATED GREEN AREAS IN THE FEDERAL CAPITAL TERRITORY, NIGERIA 1Ihuma, J.O; Tella, I. O2; Madakan, S. P.3 and Akpan, M2 1Department of Biological Sciences, Bingham University, P.M.B. 005, Karu, Nasarawa State, Nigeria Email:[email protected] 2Federal University of Technology, Yola, Nigeria, Department of Forestry and Wildlife Management. 3University of Maiduguri, Borno, Nigeria, Department of Biological Sciences ABSTRACT The diversity of frugivorous bird species in relation to tree species diversity was investigated in Designated and Reserved Green Areas of Abuja, Nigeria. The study estimated, investigated and examined trees species and avian frugivore in terms of their diversity. Point-Centered Quarter Method (PCQM) was used for vegetation analysis while random walk and focal observation was used for bird frugivore identification and enumeration. data was collected from six locations coinciding with the local administrative areas within the Federal Capital Territory. These were, the Abuja Municipal Area Council (AMAC), Abaji, Bwari, Gwagwalada, Kuje and Kwali. AMAC is designated as urban while the remaining five sites are designated as sub-urban. The highest number of fruit tree species was encountered in AMAC (30), followed by Abaji (29) while 27, 25, 19 and 11 fruit tree species were encountered in Kwali, Bwari Gwagwalada and Kuje respectively. The similarity or otherwise dissimilarity in fruit tree species composition between each pair of the enumerated sites showed Gwagwalada and Kuje as the most similar, and the similarity or otherwise dissimilarity in frugivorous bird species composition between each pair of the enumerated showed higher species similarity between the AMAC and each of the other sites, and between each pair of the sites than that of the fruit trees in the respective sites. -

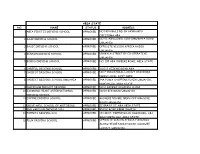

LGA Agale Agwara Bida Borgu Bosso Chanchaga Edati Gbako Gurara

LGA Agale Agwara Bida Borgu Bosso Chanchaga Edati Gbako Gurara Katcha Kontagora Lapai Lavun Magama Mariga Mashegu Mokwa Munya Paikoro Rafi Rijau Shiroro Suleja Tafa Wushishi PVC PICKUP ADDRESS Santali Road, After Lga Secretariat, Agaie Opposite Police Station, Along Agwara-Borgu Road, Agwara Lga Umaru Magajib Ward, Yahayas, Dangana Way, Bida Lga Borgu Lga New Bussa, Niger Along Leg Road, Opp. Baband Abo Primary/Junior Secondary Schoo, Near Divisional Police Station, Maikunkele, Bosso Lga Along Niger State Houseso Assembly Quarters, Western Byepass, Minna Opposite Local Govt. Secretariat Road Edati Lga, Edati Along Bida-Zungeru Road, Gbako Lga, Lemu Gwadene Primary School, Gawu Babangida Gangiarea, Along Loga Secretariat, Katcha Katcha Lga Near Hamdala Motors, Along Kontagora-Yauri Road, Kontagoa Along Minna Road, Beside Pension Office, Lapai Opposite Plice Station, Along Bida-Mokwa Road, Lavun Off Lga Secretariat Road, Magama Lga, Nasko Unguwan Sarki, Opposite Central Mosque Bangi Adogu, Near Adogu Primary School, Mashegu Off Agric Road, Mokwa Lga Munya Lga, Sabon Bari Sarkin Pawa Along Old Abuja Road, Adjacent Uk Bello Primary School, Paikoro Behind Police Barracks, Along Lagos-Kaduna Road, Rafi Lga, Kagara Dirin-Daji/Tungan Magajiya Road, Junction, Rijau Anguwan Chika- Kuta, Near Lag Secretariat, Gussoroo Road, Kuta Along Suleja Minna Road, Opp. Suleman Barau Technical Collage, Kwamba Beside The Div. Off. Station, Along Kaduna-Abuja Express Road, Sabo-Wuse, Tafa Lga Women Centre, Behind Magistration Court, Along Lemu-Gida Road, Wushishi. Along Leg Road, Opp. Baband Abo Primary/Junior Secondary Schoo, Near Divisional Police Station, Maikunkele, Bosso Lga. -

Nigeria's Constitution of 1999

PDF generated: 26 Aug 2021, 16:42 constituteproject.org Nigeria's Constitution of 1999 This complete constitution has been generated from excerpts of texts from the repository of the Comparative Constitutions Project, and distributed on constituteproject.org. constituteproject.org PDF generated: 26 Aug 2021, 16:42 Table of contents Preamble . 5 Chapter I: General Provisions . 5 Part I: Federal Republic of Nigeria . 5 Part II: Powers of the Federal Republic of Nigeria . 6 Chapter II: Fundamental Objectives and Directive Principles of State Policy . 13 Chapter III: Citizenship . 17 Chapter IV: Fundamental Rights . 20 Chapter V: The Legislature . 28 Part I: National Assembly . 28 A. Composition and Staff of National Assembly . 28 B. Procedure for Summoning and Dissolution of National Assembly . 29 C. Qualifications for Membership of National Assembly and Right of Attendance . 32 D. Elections to National Assembly . 35 E. Powers and Control over Public Funds . 36 Part II: House of Assembly of a State . 40 A. Composition and Staff of House of Assembly . 40 B. Procedure for Summoning and Dissolution of House of Assembly . 41 C. Qualification for Membership of House of Assembly and Right of Attendance . 43 D. Elections to a House of Assembly . 45 E. Powers and Control over Public Funds . 47 Chapter VI: The Executive . 50 Part I: Federal Executive . 50 A. The President of the Federation . 50 B. Establishment of Certain Federal Executive Bodies . 58 C. Public Revenue . 61 D. The Public Service of the Federation . 63 Part II: State Executive . 65 A. Governor of a State . 65 B. Establishment of Certain State Executive Bodies .