Bollington at the Time of the 1911 Census

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Appendix 4 Detailed Proposals for Each Ward – Organised by Local Area Partnership (LAP)

Appendix 4 Detailed proposals for each Ward – organised by Local Area Partnership (LAP) Proposed Wards within the Knutsford Local Area Partnership Knutsford Local Area Partnership (LAP) is situated towards the north-west of Cheshire East, and borders Wilmslow to the north-east, Macclesfield to the south-east and Congleton to the south. The M6 and M56 motorways pass through this LAP. Hourly train services link Knutsford, Plumley and Mobberley to Chester and Manchester, while in the east of this LAP hourly trains link Chelford with Crewe and Manchester. The town of Knutsford was the model for Elizabeth Gaskell's novel Cranford and scenes from the George C. Scott film Patton were filmed in the centre of Knutsford, in front of the old Town Hall. Barclays Bank employs thousands of people in IT and staff support functions at Radbroke Hall, just outside the town of Knutsford. Knutsford is home to numerous sporting teams such as Knutsford Hockey Club, Knutsford Cricket Club, Knutsford Rugby Club and Knutsford Football Club. Attractions include Tatton Park, home of the RHS Flower show, the stately homes Arley Hall, Tabley House and Peover Hall, and the Cuckooland Museum of cuckoo clocks. In detail, the proposals are: Knutsford is a historic, self-contained urban community with established extents and comprises the former County Ward of Knutsford, containing 7 polling districts. The Parish of Knutsford also mirrors the boundary of this proposal. Knutsford Town is surrounded by Green Belt which covers 58% of this proposed division. The proposed ward has excellent communications by road, motorway and rail and is bounded to the north by Tatton Park and to the east by Birkin Brook. -

Bollingtonian Spring 2015

Spring Edition 2015 Welcome to this Spring edition of Bollington Town Council’s Newsletter In this Issue: Pages 1 - 3 YOUR Chance To Help Shape Our Community’s Future Preparation and information-gathering for the Neighbourhood Plan for Bollington are now Pages 3 - 5 underway. Volunteer response Become a Bollington following public meetings in November 2014 and Town Councillor January 2015 has enabled the Steering Committee and a range of working subgroups to be set up, all involving local residents, business people and councillors. Their task: To help deliver one of the most Page 5 Civic Hall Retractable Seating Page 6 important planning documents in Bollington’s history, because this New Bowls Hut Neighbourhood Plan will aim to positively shape Bollington’s future for the next 15 years or more. Page 6 Adlington Road Play BUT our Neighbourhood Plan can only be produced successfully with Area the direct input, support and approval of the local community. That is why we want to establish the essential communication Page 7 process at this early stage with residents, local Rowland Chemists businesses, community groups and Mobile Phones organisations throughout Bollington. Ingersley Vale Mill Site Established by the Localism Act 2011, Pages 8 Neighbourhood Plans mean that local Dates for Your Diary people and communities are now able to Contact Detail directlyFancy Dressinfluence Parade and establish general planning policies for the development and use of land in their Published is by neighbourhoods. This means that our Neighbourhood Plan Bollington Town Council Town Hall will give us the opportunity to have a real say in planning Wellington Road policies and decisions covering where new houses, Bollington SK10 5JR employment opportunities, shops and Tel 01625 572985 other buildings should be located in www.bollington-tc.gov.uk Bollington. -

Bollington House, Canal Road, Congleton CW12 3AP to View

Bollington House, Canal Road, Congleton CW12 3AP Guide price 2 2 1 £500 BUTTERS JOHN BEE have TO LET this stylish apartment which is located in one of Congleton's most sought after areas and is just a very short walk from the local canal which will have you in the heart of the countryside in no time! With accommodation that includes: open plan living room / kitchen, two bedrooms Ensuite and main bathroom. Externally there is allocated parking. Call us now on 01260 280 000. To view: 01260 280000 [email protected] www.buttersjohnbee.com l 43 High Street, Congleton, Cheshire, CW12 1AU Bollington House, Canal Road, Congleton CW12 3AP Local area Congleton is a vibrant market town with the benefit of being within close proximity to Wilmslow, Alderley Edge and Prestbury which in turn offers a wide range of bars restaurants and designer shops. Congleton itself boasts a selection of independent shops within the historic town centre, as well as supermarket and high street outlets. Congleton is very much a modern active and community conscious town with museums parks two golf clubs, several sports clubs and the DaneSide Theatre. Motor way links and networks are within a ten minute drive giving you easy access to major towns and cities as well as UK holiday destinations. This combined with Congleton railway station and the local bus routes you will have no problem getting to where you want to go. Entrance hall With three ceiling spot lights. Cupboard housing electric central heating boiler. Radiator. Bollington House, Canal Road, Congleton CW12 3AP Lounge/kitchen 5.64m x 4.06m (18'6 x 13'4) Two double glazed windows to the front elevation. -

CHESHIRE. [ KELLY•S Inland Revenue Office, 4 Hibel Road, George C

352 MACCLE.:-FIELD. CHESHIRE. [ KELLY•S Inland Revenue Office, 4 Hibel road, George C. Brown, was built at a distance from the main building at a surveyor of taxes; Edwin .A.bbott, supervisor ; Sampson cost of about £1,200, & is available for about 6o patient.. Davenport Stevenson & Charles Harvey Colmar, officers In 1881 a general hospital, for 70 persons, was erected Lock-up, Town hall, Market pl. Saml. Stonehewer, keeper at a cost of about £6,ooo. In 1895 an isolation hospital Parkside County Lunatic Asylum, Chester road, Thomas was erected at a cost of £ r,2oo, containing four beds & Steele Sheldon M.B. medical superiptendent; Charles in 1891 new casual wards, for about 30 persons, were Frederick Laing M.B., C.M. assistant medical officer; built at a cost of £2,ooo; there is also accommodation Rev. Thomas W. Dix M . .A.. chaplain; Frank Tylecote, for 9 old men & 9 old women in the privileged wards, treasurer; A. C. Procter, clerk to visitors; John William a scheme which is· being tried here, and in which the Lees·, clerk; Mrs. Sarah Ann Millington, housekeeper inmates are not required to work nor to wear the Public Park, Prestbury road, George Roscoe, keeper uniform of the house ; J oseph E. Potts, master; Mrs. Theatre Royal, Catherine street, Mis·s Violet E. Greg, Hannah Potts, matron manageress & lessee . School Attendance Committee. Town Hall, Market place, Samuel Stonehewer, keeper Meets at the ·workhouse every tuesday in each month, at Macclesfield Union. 10.30 a.m . • Board day, tuesday fortnightly, at the Workhouse at Clerk, John Fred May, Church side, :Macclesfield rr o' clDck. -

Mottram St. Andrew Methodists

Mottram St. Andrew 1 2 The Parish Magazine of Mottram St. Andrew Produced jointly by the Village Hall Committee and the Parish Council RRR! It is certainly getting chilly out out of date. I hope I have rectified them in there. I hope you are all well despite this issue. As always, please get in touch on Bthe arrival of winter and that you [email protected] if you notice have had at least one mince pie by now. anything or have any comments. Thank you to those who sent me kind encouragements after my first issue - I am Please let me know if you have anything so glad that many of you enjoyed reading about life in Mottram, past, current, and it. future that you would like to share. Even if you are not sure whether anybody would I have had an exciting autumn, which I am find it interesting, drop me a line and we grateful for, although I am really looking will take it from there! forward to relaxing over Christmas. On top of publishing my first Mercury, I have Have a lovely Christmas and keep warm! performed in 16 different concerts in 2 Mana x months, visiting new places like Linlithgow near Edinburgh and Chichester in West Sussex, as well as various venues in London. If I had to pick a favourite concert out of them all, it would be my wind quintet’s (flute, oboe, clarinet, French horn and bassoon) Wigmore Hall debut! Wigmore Hall in London is one of the most renowned chamber music recital venues in the world so it was quite special, and we had such fun playing pieces that we love. -

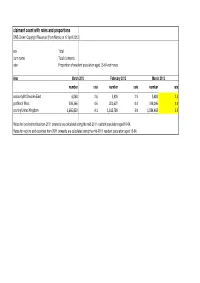

Claimant Unemployment Data

claimant count with rates and proportions ONS Crown Copyright Reserved [from Nomis on 17 April 2013] sex Total item name Total claimants rate Proportion of resident population aged 16-64 estimates Area March 2012 February 2013 March 2013 number rate number rate number rate uacounty09:Cheshire East 6,060 2.6 5,905 2.5 5,883 2.5 gor:North West 209,366 4.6 201,607 4.4 198,096 4.4 country:United Kingdom 1,666,859 4.1 1,613,789 3.9 1,584,468 3.9 Rates for local authorities from 2011 onwards are calculated using the mid-2011 resident population aged 16-64. Rates for regions and countries from 2011 onwards are calculated using the mid-2011 resident population aged 16-64. JSA count in Population (from LSOA01CD LSOA11CD LSOA11NM CHGIND March 2013 2011 Census) Claimant rate Settlement E01018574 E01018574 Cheshire East 012C U 23 1250 1.8 Alderley Edge E01018572 E01018572 Cheshire East 012A U 7 958 0.7 Alderley Edge E01018573 E01018573 Cheshire East 012B U 6 918 0.7 Alderley Edge E01018388 E01018388 Cheshire East 040B U 70 1008 6.9 Alsager E01018391 E01018391 Cheshire East 042B U 22 1205 1.8 Alsager E01018389 E01018389 Cheshire East 040C U 16 934 1.7 Alsager E01018392 E01018392 Cheshire East 042C U 19 1242 1.5 Alsager E01018390 E01018390 Cheshire East 040D U 12 955 1.3 Alsager E01018386 E01018386 Cheshire East 042A U 8 797 1.0 Alsager E01018387 E01018387 Cheshire East 040A U 8 938 0.9 Alsager E01018450 E01018450 Cheshire East 051B U 15 1338 1.1 Audlem E01018449 E01018449 Cheshire East 051A U 10 1005 1.0 Audlem E01018579 E01018579 Cheshire East 013E -

Appendix 1: Full List of Recycle Bank Sites and Materials Collected

Appendix 1: Full List of Recycle Bank Sites and Materials Collected MATERIALS RECYCLED Council Site Address Paper Glass Plastic Cans Textiles Shoes Books Oil WEEE Owned Civic Car Park Sandbach Road, Alsager Yes No No No No Yes Yes Yes No No Fanny's Croft Car Park Audley Road, Alsager Yes No No No No Yes Yes No No No Manor House Hotel Audley Road, Alsager Yes No No No No Yes Yes No Yes Yes Alsager Household Waste Hassall Road Household Waste Recycling Centre, Yes No No No No Yes Yes No Yes Yes Recycling Centre Hassall Road, Alsager, ST7 2SJ Bridge Inn Shropshire Street, Audlem, CW3 0DX Yes No No No No Yes Yes No Yes Yes Cheshire Street Car Park Cheshire Street, Audlem, CW3 0AH Yes No No No No No Yes No Yes No Lord Combermere The Square, Audlem, CW3 0AQ No Yes No No Yes No No No Yes No (Pub/Restaurant) Shroppie Fly (Pub) The Wharf, Shropshire Street, Audlem, CW3 0DX No Yes No No Yes No No No Yes No Bollington Household Waste Albert Road, Bollington, SK10 5HW Yes No No No No Yes Yes Yes Yes Yes Recycling Centre Pool Bank Car Park Palmerston Street, Bollington, SK10 5PX Yes No No No No Yes Yes Yes Yes Yes Boars Leigh Hotel Leek Road, Bosley, SK11 0PN No Yes No No No No No No Yes No Bosley St Mary's County Leek Road, Bosley, SK11 0NX Yes No No No No No No No Yes No Primary School West Street Car Park West Street, Congleton, CW12 1JR Yes No No No No Yes Yes No Yes No West Heath Shopping Centre Holmes Chapel Road, Congleton, CW12 4NB No Yes No No Yes Yes Yes No No No Tesco, Barn Road Barn Road, Congleton, CW12 1LR No Yes No No No Yes Yes No No No Appendix 1: Full List of Recycle Bank Sites and Materials Collected MATERIALS RECYCLED Council Site Address Paper Glass Plastic Cans Textiles Shoes Books Oil WEEE Owned Late Shop, St. -

The Development of a Single Point of Access for the Community Home

2020/22 Community Nursing Covid-19 Innovation/Best Practice CASE STUDY The development of a single point of access for the 1/ Personal details Community Home Visiting Service Name: Chrissy Luff Job title: CHC Assurance Manager: Interim Community Care Practitioner (During COVID) Employer: NHS England & Improvement 2/ Please describe your practice innovation I was redeployed from NHSE/I to Bollington, Disley & Poynton (BDP) Community team during the COVID pandemic. BDP Care Community has worked jointly with the Primary Care Network in response to the pandemic, co-ordinated by the Area Coach, Rhoda Gaylo. Rhoda’s passion and commitment to caring for the local health population during the global crisis was at the heart of this innovation to provide a safe refuge in the face of the pandemic. As a result, the Single Point of Access (SPA) was developed to support the BDP’s Visiting Service, to help streamline visits for urgent and non-urgent visits, including those that are associated with Covid19 symptoms. The Single Point of Access is a process where all professionals including GPs, DNs, allied health professionals, social workers and hospital trusts can access an appropriate response from the right person at the right time. Patients and/or their carers receive a phone call from an experienced clinician to establish an individual’s needs via a virtual holistic assessment. The clinician will then refer to the appropriate service, arrange a home visit or provide advice. Where a home visit is required, it will be assigned to a responder, nurse and or allied health professional, who will conduct a face to face assessment of the patient to ascertain which of these four care options is the most appropriate: 1. -

Bus Service Review – Proposals for Implementation

Appendix 1 – Summary of Proposals OFFICIAL Appendix 1 - Summary of Proposals Plan showing indicative routes outlined within the Recommended Network. 1. Summary of Changes for Final Proposals – Ordered by Consulted Upon Routes Proposed Route Current Route Consulted Network Changes from Consulted Network Proposed Routes A - Macclesfield – 19 Macclesfield – Prestbury Hourly weekday and Saturday Timetable adjusted to retain 12:00pm-13:00pm Prestbury service (except 12-1pm) using service with drivers break incorporated during off route of current 19 service. peak periods. Route unchanged. B – Nantwich – 39 – Nantwich – Wybunbury - Retention of existing 39 service Utilising of downtime on service to provide part of Wybunbury - Crewe Crewe with no timetable changes. Nantwich Town Service (to Nantwich Trade Park) to accommodate other proposals for Route G. Service remains two-hourly with minor adjustment to timetable. C - Crewe – Middlewich - 42 – Crewe – Middlewich – Retention of existing 42 service Re-routing of service via Frank Webb Avenue instead Congleton Congleton except diverting via Minshull of Minshull New Road. 85A – Crewe Bus Station – New Road instead of Frank The costs for evening services will be obtained as part Morrisons and onwards to Webb Avenue and passing of procurement of the Recommended Network. Nantwich (known as 1B Crewe Bus Eagle Bridge Medical Centre Station to Morrisons and onwards instead of Victoria Avenue. to Nantwich until September 2017) Service would operate hourly on weekdays and every 90 minutes on a Saturday, finishing earlier. D1 - Macclesfield – Forest 58 – Macclesfield – Forest Cottage Retention of existing 58 and 60 No changes proposed. Cottage – Burbage - – Burbage – Buxton services with no timetable Buxton 60 - Macclesfield – Hayfield changes. -

Spatial Distribution Update Report

Design, Planning + Prepared for: Submitted by Cheshire East Council AECOM Economics Bridgewater House, Whitworth Street, Manchester, M1 6LT July 2015 Spatial Distribution Update Report Final Report United Kingdom & Ireland AECOM Spatial Distribution Support TC-i Table of contents 1 Executive Summary 1 1.1 Introduction 1 1.2 Approach 1 1.3 Key findings 2 1.4 Options for testing the spatial distribution 5 1.5 Options analysis 10 1.6 Sustainability Appraisal and Habitats Regulation Assessment 13 1.7 Habitats Regulation Assessment 13 1.8 Recommendations 13 1.9 Implications for site allocations 15 2 Introduction and scope 17 2.1 Background to the commission 17 2.2 Council’s approach to date 17 2.3 Key objectives/issues that the commission must respond to 20 2.4 Key Requirements and Outputs 23 3 Methodology 24 3.1 Approach 24 4 Alternative spatial distribution options 27 4.2 Options for testing the spatial distribution 27 4.3 Options analysis 33 5 Summary of issues identified through the Settlement Profiles 36 5.2 Principal Towns 37 5.3 Key Service Centres 38 5.4 Local Service Centres 41 5.5 Conclusions 44 6 Vision and Strategic Priorities 47 7 Consultation and the Duty to Cooperate 49 7.1 Consultation Responses 49 7.2 Duty to Cooperate 50 8 Infrastructure 53 8.2 Public transport 53 8.3 Utilities 54 8.4 Emergency Services 54 8.5 Health facilities 54 8.6 Education 55 8.7 Leisure and culture 56 8.8 Community facilities 57 9 Highways modelling 58 10 Deliverability and Viability 62 10.2 Residential Development 62 10.3 Commercial Development 64 -

93 Ingersley Road, Bollington, Cheshire

CHARTERED SURVEYORS LAND and ESTATE AGENTS AUCTIONEERS and VALUERS 36 Park Lane Poynton Stockport Cheshire SK12 1RE telephone 01625 876331 [email protected] 2 Henshall Road Bollington Macclesfield Cheshire SK10 5HX telephone Bollington 01625 575578 [email protected] Michael G. Hart FRICS Andrew M. Hart BEng(Hons), Dip Surv, MRICS www.michael-hart.co.uk IN A DELIGHTFUL SEMI RURAL LOCATION ON THE EDGE OF THE VILLAGE HAVING FARMLAND TO THE FRONT AND REAR, A CHARMING SEMI DETACHED STONE COTTAGE WITH A PRIVATE SOUTH WEST FACING REAR GARDEN ADJOINING A BROOK. 93 INGERSLEY ROAD, BOLLINGTON, CHESHIRE. SK10 5RE £219,950 www.michael-hart.co.uk 93 INGERSLEY ROAD, BOLLINGTON, CHESHIRE. SK10 5RE OUTSIDE: Private stone-flagged garden to the rear. SERVICES: All mains services are connected. This delightful semi detached stone cottage exudes charm and a warm homely feeling. The cottage is COUNCIL TAX: Band 'C' spacious and has ample character; holding a perfect balance of modern fittings and appliances while retaining its natural rustic feel with knotty pine doors and a beautiful cast iron log burning fireplace TENURE: Freehold and free from chief rent. amongst other defining features. In addition to the main accommodation set out on two floors there is a very useful attic area. PRICE: £219,950 Located in an idyllic position on the edge of the village, the cottage looks out onto farmland from the front VIEWING: By appointment with the AGENTS Michael Hart & Company. and rear; providing eye pleasing views. The private rear garden is elegantly flag-stoned with a quaint brook passing by at the bottom. -

Middlewood Way Leaflet

contacts welcome The line carried cotton, silk, coal and and cyclists: please do not bring your From Macclesfield to Bollington, the passengers, but always struggled to horse if it is easily startled and do Way is hard-surfaced. North of Macclesfield Borough Council Ranger Service Welcome to the Middlewood Way. make a profit. It was closed in 1970 not ride faster than a trot. To find Bollington, visitors will find various Middlewood Way enquiries 01625 573998 The Way offers a 10-mile (16-km) and redeveloped for recreation as the out about stables and riding schools, firm, compacted surfaces, the Stockport Metropolitan Borough Council traffic-free route for walkers, Middlewood Way in 1985. telephone Tourist Information. accessibility of which can be cyclists and horseriders. It Middlewood Way enquiries 0161 4744512 The Macclesfield Canal was completed affected by weather. follows the line of the former British Waterways in 1831, very late for a canal - so cycling At road bridges, access is via steps Macclesfield, Bollington and Macclesfield Canal enquiries 01606 723800 late that it was almost a railway! The Middlewood Way offers easy and unless otherwise indicated. At car Marple Railway through Coal from Poynton, stone from scenic cycling and is popular for parks and crossings, our standard Tourist Information picturesque Cheshire countryside Kerridge and hats from Stockport leisure cycling year-round, especially entrance is a kissing gate, or other Macclesfield 01625 504114 and between historic mill towns. Stockport 0161 4744444 were some of the cargoes carried. The on Sundays. It forms part of Route arrangement, designed to admit For much of its length, the canal was threatened with closure in 55 of the National Cycle Network: conventional wheelchairs.