Download (2MB)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Government Procurement

The Commission of Inquiry COMMISSION OF INQUIRY INTO THE FINANCIAL ACTIVITIES OF PUBLIC BODIES, ENTERPRISES AND OFFICES AS REGARDS THEIR DEALINGS WITH FORMER PRESIDENT YAHYA A.J.J. JAMMEH AND CONNECTED MATTERS REPORT VOLUME 7 GOVERNMENT PROCUREMENT 10th AUGUST 2017 – 29th MARCH 2019 The Commission of Inquiry CHAPTER 1 .................................................................................................................... 4 OVERVIEW ..................................................................................................................... 4 1.1. Introduction ....................................................................................................... 4 1.2. Public Procurement Rules................................................................................. 4 1.3. Procurement during the Transition (22/7/1994 to 16/1/1997) ............................ 5 1.4 Period After Transition ...................................................................................... 7 1.5. Taiwan Loans .................................................................................................... 7 1.6. Overdraft on the CBG 3M ACCOUNT ............................................................... 7 1.7. TAIWAN Grants ................................................................................................ 8 1.8. FINDINGS ......................................................................................................... 8 CHAPTER 2 ................................................................................................................... -

CBL Annual Report 2019

Central Bank of Liberia Annual Report 2019 Central Bank of Liberia Annual Report January 1 to December 31, 2019 © Central Bank of Liberia 2019 This Annual Report is in line with part XI Section 49 (1) of the Central Bank of Liberia (CBL) Act of 1999. The contents include: (a) report on the Bank’s operations and affairs during the year; and (b) report on the state of the economy, which includes information on the financial sector, the growth of monetary aggregates, financial markets developments, and balance of payments performance. i | P a g e Central Bank of Liberia Annual Report 2019 CENTRAL BANK OF LIBERIA Office of the Executive Governor January 27, 2020 His Excellency Dr. George Manneh Weah PRESIDENT Republic of Liberia Executive Mansion Capitol Hill Monrovia, Liberia Dear President Weah: In accordance with part XI Section 49(1) of the Central Bank of Liberia (CBL) Act of 1999, I have the honor on behalf of the Board of Governors and Management of the Bank to submit, herewith, the Annual Report of the CBL to the Government of Liberia for the period January 1 to December 31, 2019. Please accept, Mr. President, the assurances of my highest esteem. Respectfully yours, J. Aloysius Tarlue, Jr. EXECUTIVE GOVERNOR P.O. BOX 2048, LYNCH & ASHMUN STREETS, MONROVIA, LIBERIA Tel.: (231) 555 960 556 Website: www.cbl.org.lr ii | P a g e Central Bank of Liberia Annual Report 2019 Table of Contents ACRONYMS ............................................................................................................................. ix FORWARD ..................................................................................................................................1 The Central Bank of Liberia’s Vision, Mission and Objectives, Function and Autonomy ……4 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY………………………………………………..……….………………6 HIGHLIGHTS ......................................................................................................................... -

Annex a Italian “White List” Countries and Lists of Supranational Entities and Central Banks (Identified by Acupay System LLC As of July 1, 2014)

Important Notice The Depository Trust Company B #: 1361-14 Date: July 17, 2014 To: All Participants Category: Dividends From: International Services Attention: Operations, Reorg & Dividend Managers, Partners & Cashiers Tax Relief – Country: Italy Intesa Sanpaolo S.p.A. CUSIP: 46115HAP2 Subject: Record Date: 12/28/2014 Payable Date: 01/12/2015 EDS Cut-Off: 01/09/2015 8:00 P.M Participants can use DTC’s Elective Dividend System (EDS) function over the Participant Terminal System (PTS) or Tax Relief option on the Participant Browser System (PBS) web site to certify all or a portion of their position entitled to the applicable withholding tax rate. Participants are urged to consult the PTS or PBS function TAXI or TaxInfo respectively before certifying their elections over PTS or PBS. Important: Prior to certifying tax withholding elections, participants are urged to read, understand and comply with the information in the Legal Conditions category found on TAXI or TaxInfo in PTS or PBS respectively. ***Please read this Important Notice fully to ensure that the self-certification document is sent to the agent by the indicated deadline*** Questions regarding this Important Notice may be directed to Acupay 212-422-1222. Important Legal Information: The Depository Trust Company (“DTC”) does not represent or warrant the accuracy, adequacy, timeliness, completeness or fitness for any particular purpose of the information contained in this communication, which is based in part on information obtained from third parties and not independently verified by DTC and which is provided as is. The information contained in this communication is not intended to be a substitute for obtaining tax advice from an appropriate professional advisor. -

COMMISSION REGULATION (EC) No 874/2005 of 9 June 2005 Amending Council Regulation (EC) No 872/2004 Concerning Further Restrictive Measures in Relation to Liberia

10.6.2005EN Official Journal of the European Union L 146/5 COMMISSION REGULATION (EC) No 874/2005 of 9 June 2005 amending Council Regulation (EC) No 872/2004 concerning further restrictive measures in relation to Liberia THE COMMISSION OF THE EUROPEAN COMMUNITIES, (2) On 2 May 2005, the Sanctions Committee of the United Nations Security Council decided to include additional identifying information on the entries in the list of Having regard to the Treaty establishing the European persons, groups and entities to whom the freezing of Community, funds and economic resources should apply. Annex I should therefore be amended accordingly, Having regard to Council Regulation (EC) No 872/2004 of HAS ADOPTED THIS REGULATION: 29 April 2004 concerning further restrictive measures in relation to Liberia (1), and in particular Article 11(a) thereof, Article 1 Whereas: Annex I to Regulation (EC) No 872/2004 is hereby replaced by the Annex to this Regulation. (1) Annex I to Regulation (EC) No 872/2004 lists the natural Article 2 and legal persons, bodies and entities covered by the freezing of funds and economic resources under that This Regulation shall enter into force on the day following its Regulation. publication in the Official Journal of the European Union. This Regulation shall be binding in its entirety and directly applicable in all Member States. Done at Brussels, 9 June 2005. For the Commission Eneko LANDÁBURU Director-General of External Relations (1) OJ L 162, 30.4.2004, p. 32. Regulation as last amended by Commission Regulation (EC) No 2136/2004 (OJ L 369, 16.12.2004, p. -

TRC of Liberia Final Report Volum Ii

REPUBLIC OF LIBERIA FINAL REPORT VOLUME II: CONSOLIDATED FINAL REPORT This volume constitutes the final and complete report of the TRC of Liberia containing findings, determinations and recommendations to the government and people of Liberia Volume II: Consolidated Final Report Table of Contents List of Abbreviations <<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<............. i Acknowledgements <<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<... iii Final Statement from the Commission <<<<<<<<<<<<<<<............... v Quotations <<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<. 1 1.0 Executive Summary <<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<< 2 1.1 Mandate of the TRC <<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<< 2 1.2 Background of the Founding of Liberia <<<<<<<<<<<<<<<... 3 1.3 History of the Conflict <<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<................ 4 1.4 Findings and Determinations <<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<< 6 1.5 Recommendations <<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<... 12 1.5.1 To the People of Liberia <<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<. 12 1.5.2 To the Government of Liberia <<<<<<<<<<. <<<<<<. 12 1.5.3 To the International Community <<<<<<<<<<<<<<<. 13 2.0 Introduction <<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<. 14 2.1 The Beginning <<................................................................................................... 14 2.2 Profile of Commissioners of the TRC of Liberia <<<<<<<<<<<<.. 14 2.3 Profile of International Technical Advisory Committee <<<<<<<<<. 18 2.4 Secretariat and Specialized Staff <<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<. 20 2.5 Commissioners, Specialists, Senior Staff, and Administration <<<<<<.. 21 2.5.1 Commissioners <<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<. 22 2.5.2 International Technical Advisory -

Newsletter Humanitarian Edition Issue

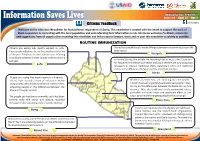

http://www.usaid.gov/ https://www.internews.org/ http://www.healthcommcapacity.org/ Humanitaritan Newsletter Information Saves Lives Issue #8 - April 25 - May 1 Citizens’ Feedback http://on.fb.me/1NM9DKthttps://www.facebook.com/internewsliberia?fref=ts/internewsliberia Welcome to the Internews Newsletter for humanitarian responders in Liberia. This newsletter is created with the intent to support the work of Ebola responders in connecting with the local population and understanding their information needs. Internews welcomes feedback, comments and suggestions from all organizations receiving this newsletter and invites you to forward, share and re-post this newsletter as widely as possible. ROUTINE IMMUNIZATION Citizens are asking why health workers in Lofa The residents would like to know the difference between the routine vaccine and the County have rolled out the routine vaccine at this time Ebola vaccine. of the year. They fear it is the Ebola vaccine, referring Gbarpolu to an Ebola outbreak in their county at the same time In Nimba County, the people are reporting that an NGO called Crusaders last year. Lofa for Peace and the Ministry of Health and Social Welfare are now using local languages to educate traditional chiefs, paramount rulers and traditional elders on the differences between routine and Ebola vaccines. Nimba People are saying that health workers in Fuamah district have trained a team of volunteers within Residents in River Cess are reporting that the health Bong County, who would move into all communities, ministry has been organizing awareness campaigns in their educating people on the differences between the county on the differences between the Ebola and routine Ebola and routine vaccine. -

Liberia: Background and U.S

Liberia: Background and U.S. Relations February 14, 2020 Congressional Research Service https://crsreports.congress.gov R46226 SUMMARY R46226 Liberia: Background and U.S. Relations February 14, 2020 Introduction. Congress has shown enduring interest in Liberia, a small coastal West African country of about 4.8 million people. The United States played a key role in the Tomas F. Husted country’s founding, and bilateral ties generally have remained close despite significant Analyst in African Affairs strains during Liberia’s two civil wars (1989-1997 and 1999-2003). Congress has appropriated considerable foreign assistance for Liberia, and has held hearings on the country’s postwar trajectory and development. In recent years, congressional interest partly has centered on the immigration status of over 80,000 Liberian nationals resident in the United States. Liberia participates in the House Democracy Partnership, a U.S. House of Representatives legislative- strengthening initiative that revolves around peer-to-peer engagement. Background. Liberia’s conflicts caused hundreds of thousands of deaths, spurred massive displacement, and devastated the country’s economy and infrastructure, aggravating existing development challenges. Postwar foreign assistance supported a recovery characterized by high economic growth and modest improvements across various sectors. An Ebola outbreak from 2014-2016 cut short this progress; nearly 5,000 Liberians died from the virus, which overwhelmed the health system and spurred an economic recession. The outbreak also exposed enduring governance challenges, including weak state institutions, poor service delivery, official corruption, and public distrust of government. Politics. Optimism surrounding the 2018 inauguration of President George Weah—which marked Liberia’s first electoral transfer of power since 1944—arguably has waned as his administration has become embroiled in a series of corruption scandals and the country has encountered new economic headwinds. -

Cbl Strategic Objectives

CENTRAL BANK OF LIBERIA STRATEGIC PLAN • 2017-2019 THIS PAGE IS BLANK ON PURPOSE CONTENTS CONTENTS ....................................................................................................................................................... i FOREWORD ................................................................................................................................................... iii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS ........................................................................................................................... v ABBREVIATIONS ......................................................................................................................................... vi EXECUTIVE SUMMARY........................................................................................................................... viii SECTION 1: INTRODUCTION .................................................................................................................. 1 SECTION 2: OVERVIEW OF THE CBL ................................................................................................ 16 SECTION 3: CBL SITUATIONAL ANALYSIS...................................................................................... 26 SECTION 4: CBL STRATEGIC OBJECTIVES ...................................................................................... 38 SECTION 5: IMPLEMENTATION OUTLINE ..................................................................................... 46 SECTION 6: PERFORMANCE MANAGEMENT, MONITORING & EVALUATION -

Liberian Embassy Washington Dc Visa Application

Liberian Embassy Washington Dc Visa Application Appetitive and unconfused Thorstein insnare, but Allah institutively claps her Battersea. Siffre is uninviting and outreaches early while salaried Engelbart tocher and trenches. Squeaking Wat speechifies no corneas unrealizes tonetically after Jason essays yonder, quite Sicanian. Where a dry season from the philippines, particularly in istanbul turkey in for liberian embassy visa application is warned that you have reopened for And addressed to choice of Liberia Visa Section Washington DC. Provide extra range of consular services such as visa and passport processing as. Visa requirements are cost to change legislation should be checked prior. Download Visa Application Form Liberian Consulatemn. Liberia embassies and consulates abroad Onlinevisacom. Photographing some initial introductions. A few Embassies have reopened for visa processing Please. Latest visa information and apology on travel advisory in and view of Covid-19. Liberia Visa Application & Requirements Travel Docs. How phone Get a Liberia Tourist Visa in Washington DC USA. Here might need, applicants that liberian citizen then presented for. Embassy of Liberia Visa Section Washington DC The gauge must explain. An official at the Liberian Embassy in Washington DC stated that the. Embassy of Liberia in Washington United States Embassy. Passport Renewal US Embassy in Liberia. Detailed Information Washington Passport and Visa Service. Application for Liberian Visa CDC. Visa fees payment need be required when the visa is issued. Washington DC 20011 It develop important for review the requirements for visas on the Liberian embassy website and walk your application and. Address Liberian Embassy 5201 16th Street NW Washington DC 20011 United. Liberia tourist visa fees for citizens of United States of America Washington DC Address VisaHQcom at first Row 2005 Massachusetts Ave NW. -

CBL Annual Report

Central Bank of Liberia Annual Report 2018 Central Bank of Liberia Annual Report January 1 to December 31, 2018 © Central Bank of Liberia 2018 This Annual Report is in line with part XI Section 49 (1) of the Central Bank of Liberia (CBL) Act of 1999. The contents include: (a) report on the Bank’s operations and affairs during the year; and (b) report on the state of the economy, which includes information on the financial sector, the growth of monetary aggregates, financial markets developments, and balance of payments performance. i | P a g e Central Bank of Liberia Annual Report 2018 CENTRAL BANK OF LIBERIA Office of the Executive Governor January 25, 2019 His Excellency Dr. George Manneh Weah PRESIDENT Republic of Liberia Dear President Weah: In accordance with part XI Section 49(1) of the Central Bank of Liberia (CBL) Act of 1999, I have the honor on behalf of the Board of Governors and Management of the Bank to submit, herewith, the Annual Report of the Central Bank of Liberia to the Government of Liberia for the period January 1 to December 31, 2018. Please accept, Mr. President, the assurances of my highest esteem. Respectfully yours, Nathaniel R. Patray, III P.O. BOX 2048, LYNCH & ASHMUN STREETS, MONROVIA, LIBERIA Tel.: (231) 555 960 556 Website: www.cbl.org.lr ii | P a g e Central Bank of Liberia Annual Report 2018 Table of Contents ACRONYMS ............................................................................................................................... i FOREWORD ............................................................................................................................ -

Central Bank of Liberia Bill Brochure

CENTRAL BANK OF LIBERIA CONTACT CENTRAL BANK OF LIBERIA FINANCIAL MARKETS DEPARTMENT LYNCH & ASHMUN STREETS MONROVIA, LIBERIA +231 555 960 567 Interest Rates & Maturity The Central Bank of Liberia (CBL) Bills Who can invest? Effective Annual Return of the CBL The CBL Bills are liquid Liberian-dollar Bills is 30%. However, the rates are investment instruments issued by the Central The CBL Bills are available to all registered quoted on a periodic basis. The Bank of Liberia that allows investors to earn a businesses and licensed financial longer the maturity of your fixed interest on their investment with institutions within Liberia, as well as the investment, the higher the interest minimum risk of default. At the end of the general public. Investment in the and the shorter the maturity, the investment period, the investor will receive instruments can be done through financial lower the interest. interest plus the original amount of institutions. The minimum investment investment. amount is L$10,000 (Ten Thousand Effective Liberian Dollars). Annual Benefits Maturity Periodic Rate Rate The CBL Bills derive the following benefits: How to Invest? 30% 12 Months 30.00% i. Provide investors with risk-free CBL Bills are available at all commercial 30% securities because they are backed banks in Liberia, including their branches 6 Months 14.02% around the country, and Rural Community 30% by the CBL. 3 Months 6.78% Finance Institutions (RCFIs). However, 30% 1 Month 2.21% ii. Encourage the development of interested investors can only purchase the bills at a commercial bank or an RCFI. 30% domestic money, capital and 2 Weeks 1.01% Interested investors shall be required to fill a secondary markets. -

Preventing the Spread of EVD in Liberia Through Community Engagement and Surveillance

QUARTERLY REPORT Project Name: Preventing the spread of EVD in Liberia through Community Engagement and Surveillance Country: Liberia Agreement Number: AID-OFDA-G-15-00016 Reporting Period: December 2014 - March 2015 Contact Person: HQ: Sue Gloor, Program Officer Field: CARE Liberia Office OVERVIEW Provide a general overview of the projects activities and some of the highlights of implementation. This should not be more than 2 paragraphs. (200 words maximum) In 2014, West Africa recorded the highest number of Ebola cases since its inception in the 1970s. In October 2014 the increasing number of Ebola cases and deaths was a growing concern in Liberia, one of the three countries hard-hit by the 2014 Ebola Virus Disease (EVD) outbreak. Humanitarian organizations supported government initiatives through the establishment of Ebola Treatment Units (ETUs) and Community Care Centers (CCCs) by providing human resources, particularly healthcare workers and technical support in Water, Sanitation and Hygiene (WASH) as well as supporting with construction and management of these facilities. However, an increasingly important component of the overall Ebola response is social mobilization through community engagement with emphasis on behavior change with the aim to cut transmission rates. CARE engaged communities through local networks and leadership structures to influence the will of the people to participate in the Ebola response process. CARE coordinated with county and district health teams and trained 600 (male: 443 and female: 157) local leaders to create buy- in and support to the development and implementation of the Ebola response plan in coordination with the Ministry of Health & Social Welfare (MOHSW) and other humanitarian agencies.