The Intertwining of Reconciliation and Displacement: a Lifeworld Hermeneutic Study of Older Adults’ Perceptions of the Finality of Life

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Amazon's Antitrust Paradox

LINA M. KHAN Amazon’s Antitrust Paradox abstract. Amazon is the titan of twenty-first century commerce. In addition to being a re- tailer, it is now a marketing platform, a delivery and logistics network, a payment service, a credit lender, an auction house, a major book publisher, a producer of television and films, a fashion designer, a hardware manufacturer, and a leading host of cloud server space. Although Amazon has clocked staggering growth, it generates meager profits, choosing to price below-cost and ex- pand widely instead. Through this strategy, the company has positioned itself at the center of e- commerce and now serves as essential infrastructure for a host of other businesses that depend upon it. Elements of the firm’s structure and conduct pose anticompetitive concerns—yet it has escaped antitrust scrutiny. This Note argues that the current framework in antitrust—specifically its pegging competi- tion to “consumer welfare,” defined as short-term price effects—is unequipped to capture the ar- chitecture of market power in the modern economy. We cannot cognize the potential harms to competition posed by Amazon’s dominance if we measure competition primarily through price and output. Specifically, current doctrine underappreciates the risk of predatory pricing and how integration across distinct business lines may prove anticompetitive. These concerns are height- ened in the context of online platforms for two reasons. First, the economics of platform markets create incentives for a company to pursue growth over profits, a strategy that investors have re- warded. Under these conditions, predatory pricing becomes highly rational—even as existing doctrine treats it as irrational and therefore implausible. -

Girl Names Registered in 1996

Baby Girl Names Registered in 1996 # Baby Girl Names # Baby Girl Names # Baby Girl Names 1 Aaliyah 1 Aiesha 1 Aleeta 1 Aamino 2 Aileen 1 Aleigha 1 Aamna 1 Ailish 2 Aleksandra 1 Aanchal 1 Ailsa 3 Alena 2 Aaryn 4 Aimee 1 Alesha 1 Aashna 1Ainslay 1 Alesia 5 Abbey 1Ainsleigh 1 Alesian 1 Abbi 4Ainsley 6 Alessandra 3 Abbie 1 Airianna 1 Alessia 2 Abbigail 1Airyn 1 Aleta 19 Abby 4 Aisha 5 Alex 1 Abear 1 Aishling 25 Alexa 1 Abena 6 Aislinn 1 Alexander 1 Abigael 1 Aiyana-Marie 128 Alexandra 32 Abigail 2Aja 2 Alexandrea 5 Abigayle 1 Ajdina 29 Alexandria 2 Abir 1 Ajsha 5 Alexia 1 Abrianna 1 Akasha 49 Alexis 1 Abrinna 1Akayla 1 Alexsandra 1 Abyen 2Akaysha 1 Alexus 1 Abygail 1Akelyn 2 Ali 2 Acacia 1 Akosua 7 Alia 1 Accacca 1 Aksana 1 Aliah 1 Ada 1 Akshpreet 1 Alice 1 Adalaine 1 Alabama 38 Alicia 1 Adan 2 Alaina 1 Alicja 1 Adanna 1 Alainah 1 Alicyn 1 Adara 20 Alana 4 Alida 1 Adarah 1 Alanah 2 Aliesha 1 Addisyn 1 Alanda 1 Alifa 1 Adele 1 Alandra 2 Alina 2 Adelle 12 Alanna 1 Aline 1 Adetola 6 Alannah 1 Alinna 1 Adrey 2 Alannis 4 Alisa 1 Adria 1Alara 1 Alisan 9 Adriana 1 Alasha 1 Alisar 6 Adrianna 2 Alaura 23 Alisha 1 Adrianne 1 Alaxandria 2 Alishia 1 Adrien 1 Alayna 1 Alisia 9 Adrienne 1 Alaynna 23 Alison 1 Aerial 1 Alayssia 9 Alissa 1 Aeriel 1 Alberta 1 Alissah 1 Afrika 1 Albertina 1 Alita 4 Aganetha 1 Alea 3 Alix 4 Agatha 2 Aleah 1 Alixandra 2 Agnes 4 Aleasha 4 Aliya 1 Ahmarie 1 Aleashea 1 Aliza 1 Ahnika 7Alecia 1 Allana 2 Aidan 2 Aleena 1 Allannha 1 Aiden 1 Aleeshya 1 Alleah Baby Girl Names Registered in 1996 Page 2 of 28 January, 2006 # Baby Girl Names -

Baby Girl Names Registered in 2001 a GOVERNMENT SERVICES

Baby Girl Names Registered in 2001 A GOVERNMENT SERVICES # Girl Names # Girl Names # Girl Names 1 A 1 Adelaide 4 Aisha 2 Aaisha 2 Adelle 1 Aisley 1 Aajah 1 Adelynn 1 Aislin 1 Aaliana 2 Adena 1 Aislinn 2 Aaliya 1 Adeoluwa 2 Aislyn 10 Aaliyah 1 Adia 1 Aislynn 1 Aalyah 1 Adiella 1 Aisyah 1 Aarona 5 Adina 1 Ai-Vy 1 Aaryanna 1 Adreana 1 Aiyana 1 Aashiyana 1 Adreanna 1 Aja 1 Aashna 7 Adria 1 Ajla 1 Aasiya 2 Adrian 1 Akanksha 1 Abaigeal 7 Adriana 1 Akasha 1 Abang 11 Adrianna 1 Akashroop 1 Abbegael 1 Adrianne 1 Akayla 1 Abbegayle 1 Adrien 1 Akaysia 15 Abbey 1 Adriene 1 Akeera 2 Abbi 3 Adrienne 1 Akeima 3 Abbie 1 Adyan 1 Akira 8 Abbigail 1 Aedan 1 Akoul 1 Abbi-Gail 1 Aeryn 1 Akrity 47 Abby 1 Aeshah 2 Alaa 3 Abbygail 1 Afra 1 Ala'a 2 Abbygale 1 Afroz 1 Alabama 1 Abbygayle 1 Afsaneh 1 Alabed 1 Abby-Jean 1 Aganetha 5 Alaina 1 Abella 1 Agar 1 Alaine 1 Abha 6 Agatha 1 Alaiya 1 Abigael 1 Agel 11 Alana 83 Abigail 2 Agnes 1 Alanah 1 Abigale 1 Aheen 4 Alanna 1 Abigayil 1 Ahein 2 Alannah 4 Abigayle 1 Ahlam 1 Alanta 1 Abir 2 Ahna 1 Alasia 1 Abrial 1 Ahtum 1 Alaura 1 Abrianna 1 Aida 1 Alaya 3 Abrielle 4 Aidan 1 Alayja 1 Abuk 2 Aideen 5 Alayna 1 Abygale 6 Aiden 1 Alaysia 3 Acacia 1 Aija 1 Alberta 1 Acadiana 1 Aika 1 Aldricia 1 Acelyn 1 Aiko 2 Alea 1 Achwiel 1 Aileen 7 Aleah 1 Adalien 1 Aiman 1 Aleasheanne 1 Adana 7 Aimee 1 Aleea 2 Adanna 2 Aimée 1 Aleesha 2 Adara 1 Aimie 2 Aleeza 1 Adawn-Rae 1 Áine 1 Aleighna 1 Addesyn 1 Ainsleigh 1 Aleighsha 1 Addisan 12 Ainsley 1 Aleika 10 Addison 1 Aira 1 Alejandra 1 Addison-Grace 1 Airianna 1 Alekxandra 1 Addyson 1 Aisa -

Federal Register/Vol. 77, No. 22/Thursday, February 2, 2012

5308 Federal Register / Vol. 77, No. 22 / Thursday, February 2, 2012 / Notices opportunity to comment on proposed Current Actions: There is no change to information; (c) ways to enhance the and/or continuing information this existing regulation. quality, utility, and clarity of the collections, as required by the Type of Review: Extension of a information to be collected; (d) ways to Paperwork Reduction Act of 1995, currently approved collection. minimize the burden of the collection of Public Law 104–13 (44 U.S.C. Affected Public: Individuals and information on respondents, including 3506(c)(2)(A)). business or other for-profit through the use of automated collection DATES: Written comments should be organizations. techniques or other forms of information received on or before April 2, 2012 to Estimated Number of Respondents: 4. technology; and (e) estimates of capital be assured of consideration. Estimated Time per Respondent: 30 or start-up costs and costs of operation, minutes. maintenance, and purchase of services ADDRESSES: Direct all written comments Estimated Total Annual Burden to provide information. to Yvette Lawrence, Internal Revenue Hours: 2. Service, room 6129, 1111 Constitution Approved: January 24, 2012. The following paragraph applies to all Yvette Lawrence, Avenue NW., Washington, DC 20224. of the collections of information covered IRS Reports Clearance Officer. FOR FURTHER INFORMATION CONTACT: by this notice: Requests for additional information or An agency may not conduct or [FR Doc. 2012–2265 Filed 2–1–12; 8:45 am] copies of the regulations should be sponsor, and a person is not required to BILLING CODE 4830–01–P directed to R. -

Office of Court Administration Family Report

OFFICE OF COURT ADMINISTRATION TEXAS JUDICIAL COUNCIL OFFICIAL DISTRICT COURT MONTHLY REPORT FOR THE MONTH OF July , 2019 COUNTY DISTRICT CLERK Sheri Woodfin MAILING ADDRESS 112 West Beauregard CITY San Angelo , TEXAS 76903 Zip PHONE 325-659-6579 FAX 325-659-3241 E-MAIL [email protected] PLEASE CHECK THE STATEMENT BELOW THAT APPLIES TO THIS REPORT: X THIS IS A COMBINED REPORT FOR ALL DISTRICT COURTS IN THE COUNTY. OR THIS IS A SEPARATE REPORT FOR THE ONLY. NAME OF DISTRICT COURT PLEASE RETURN THIS FORM NO LATER THAN 20 DAYS THE ATTACHED REPORT IS A TRUE AND ACCURATE REFLECTION OF THE RECORDS OF FOLLOWING THE END OF THE MONTH REPORTED TO: THE COURTS OF THIS COUNTY. Office of Court Administration PREPARED BY Vicki Vines P.O. Box 12066 Austin, Texas 78711 DATE 8/19/2019 / 325-659-6579 (512) 463-1625 Fax: (512) 463-1648 A.C. PHONE Printed on 08/19/2019 08:34 AM Page 1 of 104 FAMILY LAW SECTION Divorce Child Protective Title IV-D All Other Family Post-Judgment Actions ParentalTermination Rights of Parent-Child Total Cases No Divorce No DivorceProtective Law Cases Services Adoption Orders - Modification - Modification - Enforcement No Children Support Children Paternity Order UIFSA Custody Title IV-D CASES ON DOCKET Other 1. CASES PENDING FIRST OF MONTH (Should equal total family law cases pending end 287 227 85 162 0 34 25 18 231 3 47 0 271 66 354 1810 of previous month.) a. Active Cases 287 227 85 162 0 34 25 18 231 3 47 0 270 66 352 1807 b. -

Georgian Court University Fall/Winter 2018 Magazine

Volume 16 | Number 1 Fall/Winter 2018 Georgian Court University Magazine President’s Annual Report & Honor Roll of Donors 2017–2018 Georgian Court–Hackensack Meridian Health School of Nursing Celebrates 10 Years From the President Dear Alumni, Donors, Students, and Friends: Happy New Year! The holiday season is behind us, but the activities and accolades of 2018 still give us to plenty to celebrate. That is why this edition of GCU Magazine is packed with examples of good news worth sharing—with you and with those you know. First, the Georgian Court–Hackensack Meridian Health School of Nursing is celebrating its 10-year anniversary. Our first decade has produced successful health care professionals serving patients from coast to coast, and the program is among the fastest growing at GCU. In this issue of the magazine, I’d like you to meet two unforgettable alumni. Florence “Riccie” Riccobono Johnson ’45 (pp. 28–29) has worked at CBS for more than six decades and reflects on her time at 60 Minutes, where she’s been employed since 1968. Gemma Brennan ’84, ’93 (pp. 6–9), a longtime teacher, principal, and part-time GCU professor, is sharing her passion in unique ways. Likewise, our newest honorary degree recipient, His Royal Highness The Prince Edward, Earl of Wessex, shared his passion for court tennis during a September visit to GCU (p. 13). Georgian Court was at its absolute finest as the prince met students, faculty, staff, and coaches, and played several matches in the Casino. A few weeks later, I was proud to see alumni join in the fun of Reunion and Homecoming Weekend 2018 (p. -

FY19 Annual Report View Report

Annual Report 2018–19 3 Introduction 5 Metropolitan Opera Board of Directors 6 Season Repertory and Events 14 Artist Roster 16 The Financial Results 20 Our Patrons On the cover: Yannick Nézet-Séguin takes a bow after his first official performance as Jeanette Lerman-Neubauer Music Director PHOTO: JONATHAN TICHLER / MET OPERA 2 Introduction The 2018–19 season was a historic one for the Metropolitan Opera. Not only did the company present more than 200 exiting performances, but we also welcomed Yannick Nézet-Séguin as the Met’s new Jeanette Lerman- Neubauer Music Director. Maestro Nézet-Séguin is only the third conductor to hold the title of Music Director since the company’s founding in 1883. I am also happy to report that the 2018–19 season marked the fifth year running in which the company’s finances were balanced or very nearly so, as we recorded a very small deficit of less than 1% of expenses. The season opened with the premiere of a new staging of Saint-Saëns’s epic Samson et Dalila and also included three other new productions, as well as three exhilarating full cycles of Wagner’s Ring and a full slate of 18 revivals. The Live in HD series of cinema transmissions brought opera to audiences around the world for the 13th season, with ten broadcasts reaching more than two million people. Combined earned revenue for the Met (box office, media, and presentations) totaled $121 million. As in past seasons, total paid attendance for the season in the opera house was 75%. The new productions in the 2018–19 season were the work of three distinguished directors, two having had previous successes at the Met and one making his company debut. -

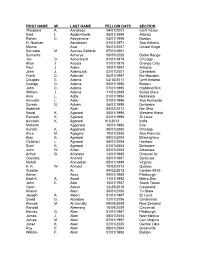

FIRST NAME MI LAST NAME FELLOW DATE SECTION Theodore A

FIRST NAME MI LAST NAME FELLOW DATE SECTION Theodore A. Aanstoos 04/01/2001 Cent Texas Said I. Abdel-Khalik 06/01/1999 Atlanta Rohan C. Abeyaratne 03/01/1998 Boston H. Norman Abramson 01/01/1971 San Antonio Memis Acar 06/01/2007 United Kingd Salvador M. Aceves-Saborio 07/01/2001 Sumanta Acharya 08/05/2008 Baton Rouge Jan D. Achenbach 01/01/1979 Chicago Allan J. Acosta 01/01/1979 Orange Cnty Paul J. Adam 10/01/1997 Arizona John J. Adamczyk 02/01/2001 Cleveland Frank C. Adamek 05/01/1997 Nw Houston Douglas E. Adams 03/18/2011 Cent Indiana George G. Adams 05/01/1995 Boston John C. Adams 07/01/1995 Highland Rim William J. Adams 11/01/2000 Santa Clara Alva L. Addy 01/01/1984 Nebraska Kenneth L. Adler 01/01/1986 San Fernando Suresh G. Advani 06/01/1999 Delaware Abdollah Afjeh 04/02/2012 Nw Ohio Naval K. Agarwal 05/01/1996 Western Wash Ramesh K. Agarwal 02/01/1994 St Louis Avinash K. Agarwal 9/1/2013 India Mahesh Aggarwal 10/01/1995 Erie Suresh K. Aggarwal 06/01/2005 Chicago Alice M. Agogino 10/01/2005 San Francisc Ajay K. Agrawal 09/01/2004 Birmingham Giridhari L. Agrawal 04/01/2004 Hartford Sunil K. Agrawal 01/01/2004 Delaware John W. Ahlen 05/01/2003 Arkansas Arthur G. Ahlstone 12/01/1988 Channel Isl Goodarz Ahmadi 03/01/1997 Syracuse Mehdi Ahmadian 05/01/1998 Virginia A. K. W. Ahmed 10/02/2012 Quebec Xiaolan Ai 04/02/2012 Canton-All-M Adnan Akay 09/01/1989 Pittsburgh Hadi K. -

San Diego County Treasurer-Tax Collector 2019-2020 Returned Property Tax Bills

SAN DIEGO COUNTY TREASURER-TAX COLLECTOR 2019-2020 RETURNED PROPERTY TAX BILLS TO SEARCH, PRESS "CTRL + F" CLICK HERE TO CHANGE MAILING ADDRESS PARCEL/BILL OWNER NAME 8579002100 11-11 GIFT TRUST 04-01-96 8579002104 11-11 GIFT TRUST 04-01-96 8579002112 11-11 GIFT TRUST 04-01-96 8679002101 11-11 GIFT TRUST 04-01-96 8679002105 11-11 GIFT TRUST 04-01-96 8679002113 11-11 GIFT TRUST 04-01-96 8779002102 11-11 GIFT TRUST 04-01-96 8779002106 11-11 GIFT TRUST 04-01-96 8779002114 11-11 GIFT TRUST 04-01-96 8879002103 11-11 GIFT TRUST 04-01-96 8879002107 11-11 GIFT TRUST 04-01-96 8879002115 11-11 GIFT TRUST 04-01-96 5331250200 1141 LAGUNA AVE L L C 2224832400 1201 VIA RAFAEL LTD 3172710300 12150 FLINT PLACE LLC 2350405100 1282 PACIFIC OAKS LLC 4891237400 1360 E MADISON AVENUE L L C 1780235100 138 SUN VILLA CT LLC 8894504458 138 SUN VILLA CT LLC 2222400700 1488 SAN PABLO L L C 1300500500 15195 HWY 76 TRUST 04-084 1473500900 152 S MYERS LLC 4230941300 1550 GARNET LLC 2754610900 15632 POMERADO ROAD L L C 1678 COUNTRY CLUB DR ESCONDIDO CA 92029 TRUST 05-07- 2325114700 18 1678 COUNTRY CLUB DR ESCONDIDO CA 92029 TRUST 05-07- 8894616148 18 2542212300 1697A LA COSTA MEADOWS L L C 2542212400 1697A LA COSTA MEADOWS L L C 6461901900 1704 CACTUS ROAD LLC 5333021200 1750 FIFTH AVENUE L L C 2542304001 180 PHOEBE STREET LLC 5392130600 1815-19 GRANADA AVENUE LLC 5392130700 1815-19 GRANADA AVENUE LLC 2643515400 18503 CALLE LA SERRA L L C 2263601300 1991 TRUST 12-02-91 AND W J K FAMILY LTD PARTNERSHIP 5650321400 1998 ENG FAMILY L L C 5683522300 1998 ENG FAMILY L L -

What Does Lina Khan's Appointment As FTC Chair Mean for Your Business?

Litigation & Arbitration Group Client Alert What Does Lina Khan’s Appointment as FTC Chair Mean for Your Business? June 25, 2021 Contact Fiona Schaeffer Andrew Wellin Eric Hyla Lena K. Bruce Partner Special Counsel Associate Associate +1 212.530.5243 +1 212.530.5432 +1 212.530.5243 +1 212.530.5028 [email protected] [email protected] [email protected] [email protected] On June 15, 2021, within hours of her Senate confirmation as a Federal Trade Commission (FTC) Commissioner, 32-year-old Lina Khan was appointed by President Biden to serve as the youngest FTC Chair in history. Khan has established herself as a progressive antitrust activist and a leader of the “New Brandeis Movement”1 that advocates for a revival of more aggressive U.S. antitrust policies and enforcement from the earlier part of the 20th century. Khan’s most widely-recognized and influential work, “Amazon’s Antitrust Paradox,” published in the Yale Law Journal in 2017 (while she was a Yale law student), argues that the current US antitrust paradigm (heavily influenced by the Chicago School) is too narrowly focused on consumer welfare and “is unequipped to capture the architecture of market power in the modern economy.”2 Because the consumer welfare standard focuses on short-term price and output effects, it is ill-equipped to address the purported harms to competition that big tech platforms raise. In her article, Khan maintains that platform markets, such as Amazon, have evaded antitrust liability because they focus on long-term growth over short-term profits – in short, they can make predatory, below-cost pricing a rational and profitable strategy, and can control the infrastructure on which their rivals depend without raising prices or reducing output in the short-term. -

Oss Personnel Files - Rg 226 Entry 224 12/23/2010

OSS PERSONNEL FILES - RG 226 ENTRY 224 12/23/2010 LAST NAME FIRST NAME M I RANK or SERIAL BOX NOTES LOCATION Aaberg Caf-3 E T-5 37541999 1 230/86/26/03 Aalbu Sigurd J S/Sgt 37091702 1 230/86/26/03 Aanonsen Olaf H Cpl 32440677 1 230/86/26/03 Abbenante Helen G Cpl A125357 1 230/86/26/03 Abbote Frank Pfc 32985690 1 230/86/26/03 Abbote John A T-3 42048684 1 230/86/26/03 Abbott Delbert H Pvt 35314960 1 230/86/26/03 Abbott Floyd H Pfc 39535381 1 230/86/26/03 Abbott Frederick K Caf-11 1 230/86/26/03 Abbott James E S/Sgt 12063651 1 230/86/26/03 Abbott James F T-5 11102233 1 230/86/26/03 Abbott Norman SP 2/c 5634486 1 230/86/26/03 Abbott Robert J Sgt 12140436 1 230/86/26/03 Abbott Victor J M/Sgt 32455694 1 230/86/26/03 Abee Robert V T-4 34437404 1 230/86/26/03 Abel Arthur A 1st Lt 1181596 1 230/86/26/03 Abel Calvin J T-5 16117938 1 230/86/26/03 Abel John C 1 230/86/26/03 Abele Charles R 1st Lt 462544 1 230/86/26/03 Abele Herbert, Jr. A 2nd Lt 1329784 1 230/86/26/03 Abendschein Norman W Sgt 33191772 1 230/86/26/03 Abernathy James D 1st Lt 343733 1 230/86/26/03 Abney James K 1 230/86/26/03 Abraham Michael K Capt 1010362 1 230/86/26/03 Abrahamovitz Moses T/Sgt 33751543 2 230/86/26/03 Abrahams Isaace L 39090318 1 230/86/26/03 Abrahamson Albert Pvt 32966288 1 230/86/26/03 Abrahamson John D P-4 1 230/86/26/03 Abrams Allen P-7 2 230/86/26/03 Abrams Leonard 2 230/86/26/03 Abrams Melville F T-4 32978088 2 230/86/26/03 Abrams Ruth B Caf-7 2 230/86/26/03 Abrignani Vincent A Maj 1297132 2 230/86/26/03 Abrogast Hazel E Caf-4 2 230/86/26/03 Abromaitis Alexander -

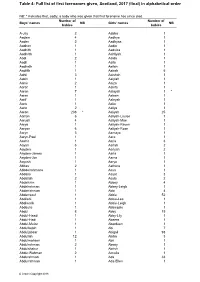

Table 4: Full List of First Forenames Given, Scotland, 2016 (Final) In

Table 4: Full list of first forenames given, Scotland, 2017 (final) in alphabetical order NB: * indicates that, sadly, a baby who was given that first forename has since died. Number of Number of Boys' names NB Girls' names NB babies babies A-Jay 2 Aabha 1 Aadam 4 Aadhya 1 Aaden 2 Aadhyaa 1 Aadhan 1 Aadia 1 Aadhith 1 Aadvika 1 Aadhrith 1 Aahliyah 1 Aadi 2 Aaida 1 Aadil 1 Aaila 1 Aadirath 1 Aailah 1 Aadrith 1 Aairah 5 Aahil 3 Aaishah 1 Aakin 1 Aaiylah 1 Aamir 2 Aaiza 1 Aaraf 1 Aakifa 1 Aaran 7 Aalayah 1 * Aarav 1 Aaleen 1 Aarif 1 Aaleyah 1 Aariv 1 Aalia 1 Aariz 2 Aaliya 1 Aaron 236 * Aaliyah 25 Aarron 6 Aaliyah-Louise 1 Aarush 4 Aaliyah-Mae 1 Aarya 1 Aaliyah-Raven 1 Aaryan 6 Aaliyah-Rose 1 Aaryn 3 Aamaya 1 Aaryn-Paul 1 Aara 1 Aashir 1 Aaria 3 Aayan 6 Aariah 2 Aayden 1 Aariyah 2 Aayden-James 1 Aarla 1 Aayden-Jon 1 Aarna 1 Aayush 1 Aarya 1 Abbas 2 Aathera 1 Abbdelrahmane 1 Aava 1 Abdalla 1 Aayat 3 Abdallah 2 Aayla 2 Abdelkrim 1 Abbey 4 Abdelrahman 1 Abbey-Leigh 1 Abderrahman 1 Abbi 4 Abderraouf 1 Abbie 52 Abdilahi 1 Abbie-Lee 1 Abdimalik 1 Abbie-Leigh 1 Abdoulie 1 Abbiegale 1 Abdul 8 Abby 19 Abdul-Haadi 1 Abby-Lily 1 Abdul-Hadi 1 Abeera 1 Abdul-Muizz 1 Aberdeen 1 Abdulfattah 1 Abi 7 Abduljabaar 1 Abigail 93 Abdullah 12 Abiha 3 Abdulmohsen 1 Abii 1 Abdulrahman 2 Abony 1 Abdulshakur 1 Abrish 1 Abdur-Rahman 2 Accalia 1 Abdurahman 1 Ada 33 Abdurrahman 1 Ada-Ellen 1 © Crown Copyright 2018 Table 4 (continued) NB: * indicates that, sadly, a baby who was given that first forename has since died Number of Number of Boys' names NB Girls' names NB