Anxiety in Action : Letters of Advice Between the Constables of East Bergholt in the Early Nineteenth Century

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

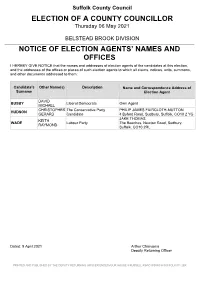

Notice of Election Agents Babergh

Suffolk County Council ELECTION OF A COUNTY COUNCILLOR Thursday 06 May 2021 BELSTEAD BROOK DIVISION NOTICE OF ELECTION AGENTS’ NAMES AND OFFICES I HEREBY GIVE NOTICE that the names and addresses of election agents of the candidates at this election, and the addresses of the offices or places of such election agents to which all claims, notices, writs, summons, and other documents addressed to them: Candidate's Other Name(s) Description Name and Correspondence Address of Surname Election Agent DAVID BUSBY Liberal Democrats Own Agent MICHAEL CHRISTOPHER The Conservative Party PHILIP JAMES FAIRCLOTH-MUTTON HUDSON GERARD Candidate 4 Byford Road, Sudbury, Suffolk, CO10 2 YG JAKE THOMAS KEITH WADE Labour Party The Beeches, Newton Road, Sudbury, RAYMOND Suffolk, CO10 2RL Dated: 9 April 2021 Arthur Charvonia Deputy Returning Officer PRINTED AND PUBLISHED BY THE DEPUTY RETURNING OFFICER ENDEAVOUR HOUSE 8 RUSSELL ROAD IPSWICH SUFFOLK IP1 2BX Suffolk County Council ELECTION OF A COUNTY COUNCILLOR Thursday 06 May 2021 COSFORD DIVISION NOTICE OF ELECTION AGENTS’ NAMES AND OFFICES I HEREBY GIVE NOTICE that the names and addresses of election agents of the candidates at this election, and the addresses of the offices or places of such election agents to which all claims, notices, writs, summons, and other documents addressed to them: Candidate's Other Name(s) Description Name and Correspondence Address of Surname Election Agent GORDON MEHRTENS ROBERT LINDSAY Green Party Bildeston House, High Street, Bildeston, JAMES Suffolk, IP7 7EX JAKE THOMAS CHRISTOPHER -

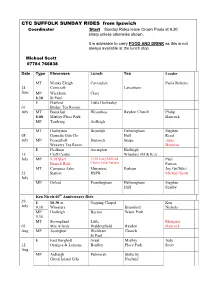

CTC SUFFOLK SUNDAY RIDES from Ipswich Coordinator Start Sunday Rides Leave Crown Pools at 9.30 Sharp Unless Otherwise Shown

CTC SUFFOLK SUNDAY RIDES from Ipswich Coordinator Start Sunday Rides leave Crown Pools at 9.30 sharp unless otherwise shown. It is advisable to carry FOOD AND DRINK as this is not always available at the lunch stop Michael Scott 07784 766838 Date Type Elevenses Lunch Tea Leader MT Monks Eleigh Cavendish Paula Roberts 24 Corncraft Lavenham June MP Wickham Clare 8.30 St Paul E Flatford Little Horkesley 01 Bridge Tea Rooms July MT Breakfast Wivenhoe Raydon Church Philip 8.00 Mistley Place Park Hancock MP Tendring Ardleigh MT Hacheston Brundish Helmingham Stephen 08 Garnetts Gdn Ctr Hall Read July MP Peasenhall Dunwich Snape Anna Weavers Tea Room Brennan E Dedham Assington Hadleigh 15 Craft Centre Wheelers (M & K’s) July MP 9.30 Start 11.30 Long Melford Paul Brunch Ride Cherry Lane Nursery Fenton MT Campsea Ashe Minsmere Parham Joy Griffiths/ 22 Station RSPB Michael Scott July MP Orford Framlingham Helmingham Stephen Hall Searby Ken Nicols 60th Anniversary Ride 29 E 10.30 at Gipping Chapel Ken July 9.30 Wheelers Bramford Nichols MP Hadleigh Bacton Water Park 9.30 MT Stowupland Little Margaret 05 Mrs Allards Waldingfield Raydon Hancock Aug MP Assington Wickham Church St Paul E East Bergholt Great Mistley Judy 12 Oranges & Lemons Bentley Place Park Scott Aug MP Ardleigh Pebmarsh Stoke by Green Island Gdn Nayland Date Type Elevenses Lunch Tea MT Breakfast South Stowmarket Michael 19 7.30 Stoke Ash Lopham Scott Aug MP Breakfast Surlingham Train Home Colin 7.30 Tivetshall Clarke E Debenham Thornham Needham Mkt River Green Alder Carr E Hollesley -

John Constable (1776-1837)

A STROLL THROUGH TATE BRITAIN John Constable (1776-1837) This two-hour talk is part of a series of twenty talks on the works of art displayed in Tate Britain, London, in June 2017. Unless otherwise mentioned all works of art are at Tate Britain. References and Copyright • The talk is given to a small group of people and all the proceeds, after the cost of the hall is deducted, are given to charity. • Our sponsored charities are Save the Children and Cancer UK. • Unless otherwise mentioned all works of art are at Tate Britain and the Tate’s online notes, display captions, articles and other information are used. • Each page has a section called ‘References’ that gives a link or links to sources of information. • Wikipedia, the Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, Khan Academy and the Art Story are used as additional sources of information. • The information from Wikipedia is under an Attribution-Share Alike Creative Commons License. • Other books and articles are used and referenced. • If I have forgotten to reference your work then please let me know and I will add a reference or delete the information. 1 A STROLL THROUGH TATE BRITAIN 1. The History of the Tate 2. From Absolute Monarch to Civil War, 1540-1650 3. From Commonwealth to the Georgians, 1650-1730 4. The Georgians, 1730-1780 5. Revolutionary Times, 1780-1810 6. Regency to Victorian, 1810-1840 7. William Blake 8. J. M. W. Turner 9. John Constable 10. The Pre-Raphaelites, 1840-1860 West galleries are 1540, 1650, 1730, 1760, 1780, 1810, 1840, 1890, 1900, 1910 East galleries are 1930, 1940, 1950, 1960, 1970, 1980, 1990, 2000 Turner Wing includes Turner, Constable, Blake and Pre-Raphaelite drawings Agenda 1. -

East Bergholt Neighbourhood Plan

2015- 2030 East Bergholt, the birthplace and Suffolk home of John Constable Version 1.1 Incorporating Examiner's Modifications July 2016 © 2016 East Bergholt Parish Council. All Rights Reserved. Page 2 of 100 Version 1.1 - July 2016 © 2016 East Bergholt Parish Council. All Rights Reserved. History Draft 1 31 Jul 2015 Ann Skippers First version for review Draft 2 8 Aug 2015 Joan Miller Update housing chapter Draft 3 17 Aug 2015 Paul Ireland Updates agreed at meeting 8 August 2015, Conversion to formatted version & completion of Developing our Plan Draft 3.1 30 Aug 2015 Paul Ireland Add two policies for reinforcing planning rules Draft 4.0 3 Sep 2015 Paul Ireland, Nigel Incorporate initial feedback & finalise Roberts, Ed Housing & Infrastructure policies. Add maps Keeble Draft 4.1 8 Sep 2015 Paul Ireland Incorporate rationale for design statement Draft 4.2 9 Sep 2015 Paul Ireland Feedback from Plan Production Group and include Character Appraisal Draft 5.0 28 Sep 2015 Plan Production Incorporate feedback on policies and text Group from Neighbourhood Plan Committee and Planning Aid England Draft 5.1 5 Oct 2015 Paul Ireland Update maps, diagrams and front picture, add focal point maps and technical updates to policies. Draft 5.2 6 Oct 2015 Paul Ireland Corrections to appendices references Draft 6.0 25 Nov 2015 Plan Production Consider Section 14 comments Group Draft 6.1 14 December Plan Production Consider and incorporate comments from 2015 Group meeting with Babergh on 9 December 2015 Draft 6.2 8 January 2016 Plan Production Consider and incorporate comments relating Group to HRA assessment Version 1.0 5 June 2016 Plan Production Incorporation of all recommendations from Group External Examiner’s Report Version 1.1 20 July 2016 Plan Production Minor corrections identified by Rachel (Referendum) Group Hogger on behalf of Babergh District Council. -

Classes and Activities in Long Melford, Lavenham and Surrounding Areas

Classes and activities in Long Melford, Lavenham and surrounding areas Empowering a Resilient Community to Celebrate Being Physically Active Education-Communication-Marketing Physical Activities All the activities in this booklet have been checked and are appropriate for clients but are also just suggestions unless stated as AOR (please see the key below). Classes can also change frequently, so please contact the venue/instructor listed prior to attending. They will also undertake a health questionnaire with you before you start. There are plenty of other classes or activities locally you might want to try. To find out more about the Active Wellbeing Programme or an activity or class near you, please contact your Physical Activity Advisor below: Nick Pringle Physical Activity Advisor – Babergh 07557 64261 [email protected] Key: Contact Price AOR At own risk (to the best of our knowledge, these activities haven’t got one or more of the following – health screen procedure prior to initial attendance, relevant instructor qualifications or insurance therefore if clients attend it is deemed at own risk) Activities in Long Melford and Lavenham Carpet Bowles Please contact AOR We are a friendly club and meet at 9.45am for a 10am start on a Tuesday morning at Lavenham Village Hall to play Carpet Bowls. You do not need to have played before and most people pick it up very quickly, and tuition is available. It is similar to outdoor bowls as you have to try to get your bowl close to the jack (white ball), but it is played indoors on a long carpet. -

Notice of Poll Babergh

Suffolk County Council ELECTION OF COUNTY COUNCILLOR FOR THE BELSTEAD BROOK DIVISION NOTICE OF POLL NOTICE IS HEREBY GIVEN THAT :- 1. A Poll for the Election of a COUNTY COUNCILLOR for the above named County Division will be held on Thursday 6 May 2021, between the hours of 7:00am and 10:00pm. 2. The number of COUNTY COUNCILLORS to be elected for the County Division is 1. 3. The names, in alphabetical order and other particulars of the candidates remaining validly nominated and the names of the persons signing the nomination papers are as follows:- SURNAME OTHER NAMES IN HOME ADDRESS DESCRIPTION PERSONS WHO SIGNED THE FULL NOMINATION PAPERS 16 Two Acres Capel St. Mary Frances Blanchette, Lee BUSBY DAVID MICHAEL Liberal Democrats Ipswich IP9 2XP Gifkins CHRISTOPHER Address in the East Suffolk The Conservative Zachary John Norman, Nathan HUDSON GERARD District Party Candidate Callum Wilson 1-2 Bourne Cottages Bourne Hill WADE KEITH RAYMOND Labour Party Tom Loader, Fiona Loader Wherstead Ipswich IP2 8NH 4. The situation of Polling Stations and the descriptions of the persons entitled to vote thereat are as follows:- POLLING POLLING STATION DESCRIPTIONS OF PERSONS DISTRICT ENTITLED TO VOTE THEREAT BBEL Belstead Village Hall Grove Hill Belstead IP8 3LU 1.000-184.000 BBST Burstall Village Hall The Street Burstall IP8 3DY 1.000-187.000 BCHA Hintlesham Community Hall Timperleys Hintlesham IP8 3PS 1.000-152.000 BCOP Copdock & Washbrook Village Hall London Road Copdock & Washbrook Ipswich IP8 3JN 1.000-915.500 BHIN Hintlesham Community Hall Timperleys Hintlesham IP8 3PS 1.000-531.000 BPNN Holiday Inn Ipswich London Road Ipswich IP2 0UA 1.000-2351.000 BPNS Pinewood - Belstead Brook Muthu Hotel Belstead Road Ipswich IP2 9HB 1.000-923.000 BSPR Sproughton - Tithe Barn Lower Street Sproughton IP8 3AA 1.000-1160.000 BWHE Wherstead Village Hall Off The Street Wherstead IP9 2AH 1.000-244.000 5. -

SUFFOLK COUNTY•RECORDS. the Principal Justice of the Peace In

SUFFOLK COUNTY•RECORDS. The principal justice of the peace in each county is the custos rotulorum or keeper of the records ; the other justices were, formerly, custodes or conservatores pacis, who claimed their power by prescription, or were bound to exercise it by the tenure of their lands, or were chosen by the freeholders in full County Court before the sheriff. After the deposition of Edward II. the election of the conservators of the peace was taken from the people and given to the Kirig. The statute 34 Edw. III. c.1 gave the ,conservators of the peace power of trying felonies, when they acquired the appellation of justices. After 1590 they were ap- pointed to keep the peace in the particular county named, and to enquire of, and to determine .offences in such county committed. It was ordained by Statute 18 Edw. III., st. ,2, c: 2, that two or three of the best reputation in each' county shall be' assigned to be keepers of the peace. By Statute 34 Edw. III. their number was increased to four, and in the reign.of Richard II. their number in each county was eight, which number was further enlarged the growth of the number of statute laws committed from time to time to the charge of the justices of the peace. Any two or more justices of the peace are em- powered by' commissionto hear and determine offences SUFFOLK COUNTY RECORDS. 145 which is the ground of their criminal jurisdiction at Quarter Sessions. " Besides the jurisdiction which the justices of each county at large exercise, in these and other matters at Quarter Sessions, authority is moreover given by various statutes to the justices acting for the several divisions into which' counties are for that purpose distributed, to transact different descriptions of business at special sessions." The Court of General Quarter Sessions of the Peace is a Court that must be held in each county once in every quarter of a year. -

East Bergholt - Colchester 93/94

Ipswich - Capel St Mary - East Bergholt - Colchester 93/94 Monday to Friday (Except Bank Holidays) Saturday Service X93 93 93A 93 93 93 94 93 93 93 93 93 93 93 93 93 93 93 Operator IB IB IB IB IB IB IB IB IB IB IB IB IB IB IB IB IB IB Service Restrictions SchE Ipswich, Old Cattle Market Bus Station (J) 0635 0810 0950 1150 1350 1445 1500 1645 1800 0650 0810 0950 1150 1350 1500 1645 1800 Ipswich, Railway Station (R2) 0545 0638 0815 0954 1154 1354 1504 1649 1804 0654 0814 0954 1154 1354 1504 1649 1804 Ipswich, Railway Station (R4) 1449 Chantry Park, Robin Drive (adj) 0549 0643 0822 1001 1201 1401 1511 1656 1811 0701 0821 1001 1201 1401 1511 1656 1811 Washbrook, Brook Inn (opp) 0648 0828 1006 1206 1406 1516 1701 1816 0706 0826 1006 1206 1406 1516 1701 1816 Copdock, Folly Lane (opp) 0652 0832 1010 1210 1410 1520 1704 1820 0710 0830 1010 1210 1410 1520 1704 1820 Bourne Bridge, Petrol Station (adj) 1455 Wherstead, The Street (adj) 1457 Tattingstone, White Horse (opp) 1501 Tattingstone, Wheatsheaf (o/s) 1505 Bentley, Memorial (opp) 1509 Capel St Mary, White Horse (opp) 0600 0656 0836 1013 1213 1413 1513 1523 1707 1823 0713 0833 1013 1213 1413 1523 1707 1823 Capel St Mary, Post Box (opp) 0658 0840 1015 1215 1415 1515 1525 1709 1825 0715 0835 1015 1215 1415 1525 1709 1825 East Bergholt, Four Sisters (S-bound) 0706 0848 1023 1223 1423 1523 1533 1717 1833 0723 0843 1023 1223 1423 1533 1717 1833 East Bergholt, High School (inside) 0853 1528 East Bergholt, Lambe School Hall (o/s) 0709 1026 1226 1426 1536 1720 1836 0726 0846 1026 1226 1426 1536 1720 -

Red Deer R. S. Adair

322 NOTES. RED DEER. NOTES. Seeing a photograph of a red-deer's head in the current number of the Archologica1 Society's Proceedings, I think the enclosed may be of interest. It is of one of a pair of fossilized red deer heads taken from the river Waveney, out of a hole, 6 feet belowthe river bed, washed out by a floodin July, 1913. The other pair is almost equally perfect and they are preserved at Flixton Hall. R. SHAFTOADAIR,Bt. MEASUREMENTS. Length on outer curve .. 31 ins. Splay at tips .. 35 ins. Girth, beam above bay 71- ins. Length brow antler .. 15/ ins. Widest spread •• .. 39/ ins. 12 points. RED DEER ANTLERS. GENERAL INDEX TO VOL. XX. Diss, 141 Acton, 74, 102 Drinkstone, 75, 140 Aldeburgh, 140 Dunwich, 301 Alderton, 140 Dunthorne MSS, 147 Alpheton, 74 Archdeacons, Norwich, 11 Ashfi eld, Great, Cross, 280 East Bergholt, 168 Austin Friars, 36 Elmham, South, 104, 141 ; St. Peter's Hall, 48 Elmsett, 141 Badingham, 234 Erwarton, 298 Bardwell, 291 Everard, Bishop of Norwich, 186 Barnham, 140 Excursions- Barton, Great, 74 1928 .. 93 Bergholt, see East Bergholt Yarmouth, Gorleston and Burgh Box ford, 101 Castle Bradfield Combust, 140 Debenham, Framsden and Otley Bradley, Little, 43 Polstead, Boxford, Chilton, Acton , Bramfield, 140 Long Melford and Kentwell Brasses at Great Thurlow, 43 ; Hall at Little Bradley, 43 South Elmham district, Rumburgh, Bricett, Great, 140 Wissett and Halesworth Brockley, 75 1929 .. 233 Bruisyard, 235 Framlingham, Dennington, Bading- Bull, Anthony, 200 ham, Sibton and Bruisyard Bull, John, 200 Rushbrook, Hawstead and Stan- Burgate, 75 ningfield Burgh Castle, 94 Newmarket and district Bury, Limitation, 41 Trimley, Felixstowe, Nacton, Butley Priory, 292 Alnesbourne and Broke Hall Buxhall, 140 1930 . -

Welcome to East Bergholt

WELCOME TO EAST BERGHOLT This booklet comes to you with the compliments of St Mary’s Church who have published it. It contains a variety of useful information, which we hope will help you settle in. As village life is very active, by the time you receive this, some items may be out of date! In addition to this booklet you will receive a free copy of the East Bergholt Parish Magazine every month, which is full of useful information and village news. Many local tradesmen and services advertise in this magazine. Copyright belongs to the Wardens and PCC. Revised January 2020 2 Contents CHURCHES .................................................................................................................................. 5 St Mary the Virgin, Church of England ................................................................................... 5 Ministry of Welcome and Fundraising ................................................................................... 6 St Mary’s Choir ....................................................................................................................... 6 Bell Ringers, St Mary’s Church ............................................................................................... 6 East Bergholt Congregational Church .................................................................................... 6 Methodist Church................................................................................................................... 6 Colchester & District Jewish Community .............................................................................. -

NOTICE of UNCONTESTED ELECTION Election of a Town

NOTICE OF UNCONTESTED ELECTION Babergh Election of a Town Councillor for (Sudbury) Elm & Hillside on Thursday 2 May 2019 I, being the Returning Officer at the above election, report that the person whose name appears below was duly elected Town Councillor for (Sudbury) Elm & Hillside. Name of Candidate Home Address Description (if any) CRESSWELL (Address in Babergh) Labour Party Luke Matthew Dated Thursday 4 April 2019 Arthur Charvonia Returning Officer Printed and published by the Returning Officer, Endeavour House, 8 Russell Road, Ipswich, Suffolk, IP1 2BX NOTICE OF UNCONTESTED ELECTION Babergh Election of Town Councillors for (Sudbury) Sudbury East on Thursday 2 May 2019 I, being the Returning Officer at the above election, report that the persons whose names appear below were duly elected Town Councillors for (Sudbury) Sudbury East. Name of Candidate Home Address Description (if any) CRESSWELL 18 Borehamgate, Sudbury, CO10 Labour Party Trevor 2EG OWEN Hill View, High Street, Acton, Labour Party Alison Sudbury, Suffolk Dated Thursday 4 April 2019 Arthur Charvonia Returning Officer Printed and published by the Returning Officer, Endeavour House, 8 Russell Road, Ipswich, Suffolk, IP1 2BX NOTICE OF UNCONTESTED ELECTION Babergh Election of Parish Councillors for Acton on Thursday 2 May 2019 I, being the Returning Officer at the above election, report that the persons whose names appear below were duly elected Parish Councillors for Acton. Name of Candidate Home Address Description (if any) ANTILL Jackdaws, Newmans Green, Nicholas Paul -

![DIRECTORY.] EAST BERGHOLT. [SUFFOLK.J](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/9355/directory-east-bergholt-suffolk-j-2569355.webp)

DIRECTORY.] EAST BERGHOLT. [SUFFOLK.J

DIRECTORY.] 721 EAST BERGHOLT. [SUFFOLK.j Free school in this parish, and £.500 were also left by Mr. amounted in 1861 to 678, and the parish contains 2,156 Edward Holland, the late proprietor of Benhall Lodge, for acres, of various soils, but chiefly clay. the same purpose. There are also National and Infant schools at Benhall Green, and a school at Benhall Street, supported by the Rev. Edmund IIollond, M.A.: the number PosT OFFICE.-Isaac Batho, receiver. Letters arrive of children educated at these establishments exceeds 100. from Saxmundham at 6.30 a.m.; dispatched at 6.30 p.m. Benhall Lodge, situated in a large and beautifully wooded The nearest money order office is at Saxmundham park, is the residence of the Rev. Edmund Holland, M.A., Free School, David Reynolds, jun. master who is lord of the manor and principal landowner. The CARRIER.-Edmunds, passing through to Ipswich, tuesday chief crops are wheat, barley, beans, &c. The population & friday Blakiston Rev. Horace Mann, B.D. Burrows Thomas, farmer N ewson George, brick maker [vicar], Vicarage Capon James, bailiff to Rev. E. Holland Plant Hobert, farmer & cattle dealer Burrows Mr. Jarnes Chambers William, farmer Hackham Rufus, relieving officer & re. Ford Mr. John Denny Waiter, hurdle maker gistrar of births & deaths Hollond Rev. Edmund, M.A. Benhall Easter John, farmer Reynolds David, sen. miller & farmer lodge; & 33 Hyde Park gardens, Elmy Durrant, gardener Robinson Georgc, farmer London 10 Freeman Edward, farmer Robinson Robert, coach builder (estab- Watkins Rev. Edwin Arthur [C"urate] Garnham George, farmer lished, 1772) COMMERCIAL.