Papilio Series) 2006

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Wild Species 2010 the GENERAL STATUS of SPECIES in CANADA

Wild Species 2010 THE GENERAL STATUS OF SPECIES IN CANADA Canadian Endangered Species Conservation Council National General Status Working Group This report is a product from the collaboration of all provincial and territorial governments in Canada, and of the federal government. Canadian Endangered Species Conservation Council (CESCC). 2011. Wild Species 2010: The General Status of Species in Canada. National General Status Working Group: 302 pp. Available in French under title: Espèces sauvages 2010: La situation générale des espèces au Canada. ii Abstract Wild Species 2010 is the third report of the series after 2000 and 2005. The aim of the Wild Species series is to provide an overview on which species occur in Canada, in which provinces, territories or ocean regions they occur, and what is their status. Each species assessed in this report received a rank among the following categories: Extinct (0.2), Extirpated (0.1), At Risk (1), May Be At Risk (2), Sensitive (3), Secure (4), Undetermined (5), Not Assessed (6), Exotic (7) or Accidental (8). In the 2010 report, 11 950 species were assessed. Many taxonomic groups that were first assessed in the previous Wild Species reports were reassessed, such as vascular plants, freshwater mussels, odonates, butterflies, crayfishes, amphibians, reptiles, birds and mammals. Other taxonomic groups are assessed for the first time in the Wild Species 2010 report, namely lichens, mosses, spiders, predaceous diving beetles, ground beetles (including the reassessment of tiger beetles), lady beetles, bumblebees, black flies, horse flies, mosquitoes, and some selected macromoths. The overall results of this report show that the majority of Canada’s wild species are ranked Secure. -

A Reconnaissance of Population Genetic Variation in Arctic and Subarctic Sulfur Butterflies (Colias Spp.; Lepidoptera, Pieridae)

1614 A reconnaissance of population genetic variation in arctic and subarctic sulfur butterflies (Colias spp.; Lepidoptera, Pieridae) Christopher W. Wheat, Ward B. Watt, and Christian L. Boutwell Abstract: Genotype–phenotype–environment interactions in temperate-zone species of Colias Fabricius, 1807 have been well studied in evolutionary terms. Arctic and alpine habitats present a different range of ecological, especially thermal, conditions under which such work could be extended across species and higher clades. To this end, we survey variation in three genes that code for phosphoglucose isomerase (PGI), phosphoglucomutase (PGM), and glucose-6-phosphate dehydrogenase (G6PD) in seven arctic and alpine Colias taxa (one only for G6PD). These genes are highly polymor- phic in all taxa studied. Patterns of variation for the PGI gene in these northern taxa suggest that the balancing selec- tion seen at this gene in temperate-zone taxa may extend throughout northern North America. Comparative study of these taxa may thus give insight into the mechanisms driving genetic differentiation among subspecies, species, and broader clades, supporting the study of both micro- and macro-evolutionary questions. Résumé : L’étude des interactions génotype–phénotype–environnement chez les papillons Colias Fabricius, 1807 de la région tempérée s’est faite dans une perspective évolutive. Les habitats arctiques et alpins offrent une gamme différente de conditions écologiques et, en particulier, thermiques dans lesquelles un tel travail peut s’étendre au niveau des espè- ces et des clades supérieurs. Dans ce but, nous avons étudié la variation de trois gènes — ceux de la phosphoglucose isomérase (PGI), de la phosphoglucomutase (PGM) et de la glucose-6-phosphate déshydrogénase (G6PD) — chez sept taxons de Colias arctiques et alpins (un seul taxon pour G6PD). -

Taxonomy, Distribution and Biology of the Genus Cercyonis (Satyridae)

1969 Journal of the Lepidopterists' Society 165 TAXONOMY, DISTRIBUTION AND BIOLOGY OF THE GENUS CERCYONIS (SATYRIDAE). 1. CHARACTERISTICS OF THE GENUS THOMAS C. EMMEL Department of Zoology, The University of Florida, Gainesville Evolution of butterflies in the satyrid genus Cercyonis has produced a complex of species groups and variable populations in North America that has not been reviewed thoroughly since the last century. The pur pose of this paper and others to follow in the series is to provide a critical, modern synthesis of taxonomic, distributional and biological information on all species and subspecies within the genus, based on extensive studies by the author from 1960 to the present. In future papers, each species group will be treated intensively, with plates of both sexes of adults of all subspecies, larvae, pupae, figures of eggs, genitalia, androconia, antennae and other important morphological characters, and chromosomes. Genetic data and hyblidization crosses will also be summarized in the present series from mateIial to be pub lished in full elsewhere. TAXONOMY The Nearctic genus Cercyonis has had over thirty specific, subspecif'ic, or varietal names applied to it, and no taxonomic revision has been at tempted since the 1880s (Edwards, 1880). On the basis of extensive field work, examination of over 5,000 adult C ercyonis specimens, rearing of many of the named forms, and studies of external and internal morphology of all these forms, the following new taxonomic treatment is proposed.l 1. Cercyonis sthenele (Boisduval, 1852) a. sthenele sthenele (Boisduval, 1852) b. sthenele silvestris (Edwards, 1861) c. sthenele paulus (Edwards, 1879) behrii (Grinnell, 19(5) d. -

Papilio (New Series) #24 2016 Issn 2372-9449

PAPILIO (NEW SERIES) #24 2016 ISSN 2372-9449 MEAD’S BUTTERFLIES IN COLORADO, 1871 by James A. Scott, Ph.D. in entomology, University of California Berkeley, 1972 (e-mail: [email protected]) Table of Contents Introduction………………………………………………………..……….……………….p. 1 Locations of Localities Mentioned Below…………………………………..……..……….p. 7 Summary of Butterflies Collected at Mead’s Major Localities………………….…..……..p. 8 Mead’s Butterflies, Sorted by Butterfly Species…………………………………………..p. 11 Diary of Mead’s Travels and Butterflies Collected……………………………….……….p. 43 Identity of Mead’s Field Names for Butterflies he Collected……………………….…….p. 64 Discussion and Conclusions………………………………………………….……………p. 66 Acknowledgments………………………………………………………….……………...p. 67 Literature Cited……………………………………………………………….………...….p. 67 Table 1………………………………………………………………………….………..….p. 6 Table 2……………………………………………………………………………………..p. 37 Introduction Theodore L. Mead (1852-1936) visited central Colorado from June to September 1871 to collect butterflies. Considerable effort has been spent trying to determine the identities of the butterflies he collected for his future father-in-law William Henry Edwards, and where he collected them. Brown (1956) tried to deduce his itinerary based on the specimens and the few letters etc. available to him then. Brown (1964-1987) designated lectotypes and neotypes for the names of the butterflies that William Henry Edwards described, including 24 based on Mead’s specimens. Brown & Brown (1996) published many later-discovered letters written by Mead describing his travels and collections. Calhoun (2013) purchased Mead’s journal and published Mead’s brief journal descriptions of his collecting efforts and his travels by stage and horseback and walking, and Calhoun commented on some of the butterflies he collected (especially lectotypes). Calhoun (2015a) published an abbreviated summary of Mead’s travels using those improved locations from the journal etc., and detailed the type localities of some of the butterflies named from Mead specimens. -

Profiles of Colorado Roadless Areas

PROFILES OF COLORADO ROADLESS AREAS Prepared by the USDA Forest Service, Rocky Mountain Region July 23, 2008 INTENTIONALLY LEFT BLANK 2 3 TABLE OF CONTENTS ARAPAHO-ROOSEVELT NATIONAL FOREST ......................................................................................................10 Bard Creek (23,000 acres) .......................................................................................................................................10 Byers Peak (10,200 acres)........................................................................................................................................12 Cache la Poudre Adjacent Area (3,200 acres)..........................................................................................................13 Cherokee Park (7,600 acres) ....................................................................................................................................14 Comanche Peak Adjacent Areas A - H (45,200 acres).............................................................................................15 Copper Mountain (13,500 acres) .............................................................................................................................19 Crosier Mountain (7,200 acres) ...............................................................................................................................20 Gold Run (6,600 acres) ............................................................................................................................................21 -

The Radiation of Satyrini Butterflies (Nymphalidae: Satyrinae): A

Zoological Journal of the Linnean Society, 2011, 161, 64–87. With 8 figures The radiation of Satyrini butterflies (Nymphalidae: Satyrinae): a challenge for phylogenetic methods CARLOS PEÑA1,2*, SÖREN NYLIN1 and NIKLAS WAHLBERG1,3 1Department of Zoology, Stockholm University, 106 91 Stockholm, Sweden 2Museo de Historia Natural, Universidad Nacional Mayor de San Marcos, Av. Arenales 1256, Apartado 14-0434, Lima-14, Peru 3Laboratory of Genetics, Department of Biology, University of Turku, 20014 Turku, Finland Received 24 February 2009; accepted for publication 1 September 2009 We have inferred the most comprehensive phylogenetic hypothesis to date of butterflies in the tribe Satyrini. In order to obtain a hypothesis of relationships, we used maximum parsimony and model-based methods with 4435 bp of DNA sequences from mitochondrial and nuclear genes for 179 taxa (130 genera and eight out-groups). We estimated dates of origin and diversification for major clades, and performed a biogeographic analysis using a dispersal–vicariance framework, in order to infer a scenario of the biogeographical history of the group. We found long-branch taxa that affected the accuracy of all three methods. Moreover, different methods produced incongruent phylogenies. We found that Satyrini appeared around 42 Mya in either the Neotropical or the Eastern Palaearctic, Oriental, and/or Indo-Australian regions, and underwent a quick radiation between 32 and 24 Mya, during which time most of its component subtribes originated. Several factors might have been important for the diversification of Satyrini: the ability to feed on grasses; early habitat shift into open, non-forest habitats; and geographic bridges, which permitted dispersal over marine barriers, enabling the geographic expansions of ancestors to new environ- ments that provided opportunities for geographic differentiation, and diversification. -

MOTHS and BUTTERFLIES LEPIDOPTERA DISTRIBUTION DATA SOURCES (LEPIDOPTERA) * Detailed Distributional Information Has Been J.D

MOTHS AND BUTTERFLIES LEPIDOPTERA DISTRIBUTION DATA SOURCES (LEPIDOPTERA) * Detailed distributional information has been J.D. Lafontaine published for only a few groups of Lepidoptera in western Biological Resources Program, Agriculture and Agri-food Canada. Scott (1986) gives good distribution maps for Canada butterflies in North America but these are generalized shade Central Experimental Farm Ottawa, Ontario K1A 0C6 maps that give no detail within the Montane Cordillera Ecozone. A series of memoirs on the Inchworms (family and Geometridae) of Canada by McGuffin (1967, 1972, 1977, 1981, 1987) and Bolte (1990) cover about 3/4 of the Canadian J.T. Troubridge fauna and include dot maps for most species. A long term project on the “Forest Lepidoptera of Canada” resulted in a Pacific Agri-Food Research Centre (Agassiz) four volume series on Lepidoptera that feed on trees in Agriculture and Agri-Food Canada Canada and these also give dot maps for most species Box 1000, Agassiz, B.C. V0M 1A0 (McGugan, 1958; Prentice, 1962, 1963, 1965). Dot maps for three groups of Cutworm Moths (Family Noctuidae): the subfamily Plusiinae (Lafontaine and Poole, 1991), the subfamilies Cuculliinae and Psaphidinae (Poole, 1995), and ABSTRACT the tribe Noctuini (subfamily Noctuinae) (Lafontaine, 1998) have also been published. Most fascicles in The Moths of The Montane Cordillera Ecozone of British Columbia America North of Mexico series (e.g. Ferguson, 1971-72, and southwestern Alberta supports a diverse fauna with over 1978; Franclemont, 1973; Hodges, 1971, 1986; Lafontaine, 2,000 species of butterflies and moths (Order Lepidoptera) 1987; Munroe, 1972-74, 1976; Neunzig, 1986, 1990, 1997) recorded to date. -

CA Checklist of Butterflies of Tulare County

Checklist of Buerflies of Tulare County hp://www.natureali.org/Tularebuerflychecklist.htm Tulare County Buerfly Checklist Compiled by Ken Davenport & designed by Alison Sheehey Swallowtails (Family Papilionidae) Parnassians (Subfamily Parnassiinae) A series of simple checklists Clodius Parnassian Parnassius clodius for use in the field Sierra Nevada Parnassian Parnassius behrii Kern Amphibian Checklist Kern Bird Checklist Swallowtails (Subfamily Papilioninae) Kern Butterfly Checklist Pipevine Swallowtail Battus philenor Tulare Butterfly Checklist Black Swallowtail Papilio polyxenes Kern Dragonfly Checklist Checklist of Exotic Animals Anise Swallowtail Papilio zelicaon (incl. nitra) introduced to Kern County Indra Swallowtail Papilio indra Kern Fish Checklist Giant Swallowtail Papilio cresphontes Kern Mammal Checklist Kern Reptile Checklist Western Tiger Swallowtail Papilio rutulus Checklist of Sensitive Species Two-tailed Swallowtail Papilio multicaudata found in Kern County Pale Swallowtail Papilio eurymedon Whites and Sulphurs (Family Pieridae) Wildflowers Whites (Subfamily Pierinae) Hodgepodge of Insect Pine White Neophasia menapia Photos Nature Ali Wild Wanderings Becker's White Pontia beckerii Spring White Pontia sisymbrii Checkered White Pontia protodice Western White Pontia occidentalis The Butterfly Digest by Cabbage White Pieris rapae Bruce Webb - A digest of butterfly discussion around Large Marble Euchloe ausonides the nation. Frontispiece: 1 of 6 12/26/10 9:26 PM Checklist of Buerflies of Tulare County hp://www.natureali.org/Tularebuerflychecklist.htm -

Edings of The

Proceedings of the FIRE HISTORYIISTORY WORKSHOP October 20-24, 1980 Tucson, Arizona General Technical Report RM.81 Rocky Mountain Forest and Range Experiment Station Forest Service U.S. Department of Agriculture Dedication The attendees of The Fire History Workshop wish to dedicate these proceedings to Mr. Harold Weaver in recognition of his early work in applying the science of dendrochronology in the determination of forest fire histories; for his pioneering leadership in the use of prescribed fire in ponderosa pine management; and for his continued interest in the effects of fire on various ecosystems. Stokes, Marvin A., and John H. Dieterich, tech. coord. 1980. Proceedings of the fire history workshop. October 20-24, 1980, Tucson, Arizona. USDA Forest Service General Technical Report RM-81, 142 p. Rocky Mountain Forest and Range Experiment Station, Fort Collins, Cob. The purpose of the workshop was to exchange information on sampling procedures, research methodologies, preparation and interpretation of specimen material, terminology, and the appli- cation and significance of findings, emphasizing the relationship of dendrochronology procedures to fire history interpretations. Proceedings of the FIRE HISTORY WORKSHOP October 20.24, 1980 Tucson, Arizona Marvin A. Stokes and John H. Dieterich Technical Coordinators Sponsored By: Rocky Mountain Forest and Range Experiment Station Forest Service, U.S. Department of Agriculture and Laboratory of Tree.Ring Research University of Arizona General Technical Report RM-81 Forest Service Rocky Mountain Forest and Range U.S. Department of Agriculture Experiment Station Fort Collins, Colorado Foreword the Fire has played a role in shaping many of the the process of identifying and describing plant communities found in the world today. -

Geographic Names

GEOGRAPHIC NAMES CORRECT ORTHOGRAPHY OF GEOGRAPHIC NAMES ? REVISED TO JANUARY, 1911 WASHINGTON GOVERNMENT PRINTING OFFICE 1911 PREPARED FOR USE IN THE GOVERNMENT PRINTING OFFICE BY THE UNITED STATES GEOGRAPHIC BOARD WASHINGTON, D. C, JANUARY, 1911 ) CORRECT ORTHOGRAPHY OF GEOGRAPHIC NAMES. The following list of geographic names includes all decisions on spelling rendered by the United States Geographic Board to and including December 7, 1910. Adopted forms are shown by bold-face type, rejected forms by italic, and revisions of previous decisions by an asterisk (*). Aalplaus ; see Alplaus. Acoma; township, McLeod County, Minn. Abagadasset; point, Kennebec River, Saga- (Not Aconia.) dahoc County, Me. (Not Abagadusset. AQores ; see Azores. Abatan; river, southwest part of Bohol, Acquasco; see Aquaseo. discharging into Maribojoc Bay. (Not Acquia; see Aquia. Abalan nor Abalon.) Acworth; railroad station and town, Cobb Aberjona; river, IVIiddlesex County, Mass. County, Ga. (Not Ackworth.) (Not Abbajona.) Adam; island, Chesapeake Bay, Dorchester Abino; point, in Canada, near east end of County, Md. (Not Adam's nor Adams.) Lake Erie. (Not Abineau nor Albino.) Adams; creek, Chatham County, Ga. (Not Aboite; railroad station, Allen County, Adams's.) Ind. (Not Aboit.) Adams; township. Warren County, Ind. AJjoo-shehr ; see Bushire. (Not J. Q. Adams.) Abookeer; AhouJcir; see Abukir. Adam's Creek; see Cunningham. Ahou Hamad; see Abu Hamed. Adams Fall; ledge in New Haven Harbor, Fall.) Abram ; creek in Grant and Mineral Coun- Conn. (Not Adam's ties, W. Va. (Not Abraham.) Adel; see Somali. Abram; see Shimmo. Adelina; town, Calvert County, Md. (Not Abruad ; see Riad. Adalina.) Absaroka; range of mountains in and near Aderhold; ferry over Chattahoochee River, Yellowstone National Park. -

Idaho: Lewis Clark Byway Guide.Pdf

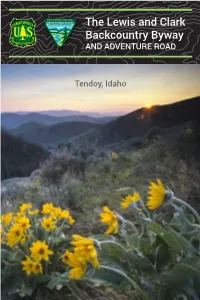

The Lewis and Clark Backcountry Byway AND ADVENTURE ROAD Tendoy, Idaho Meriwether Lewis’s journal entry on August 18, 1805 —American Philosophical Society The Lewis and Clark Back Country Byway AND ADVENTURE ROAD Tendoy, Idaho The Lewis and Clark Back Country Byway and Adventure Road is a 36 mile loop drive through a beautiful and historic landscape on the Lewis and Clark National Historic Trail and the Continental Divide National Scenic Trail. The mountains, evergreen forests, high desert canyons, and grassy foothills look much the same today as when the Lewis and Clark Expedition passed through in 1805. THE PUBLIC LANDS CENTER Salmon-Challis National Forest and BLM Salmon Field Office 1206 S. Challis Street / Salmon, ID 83467 / (208)756-5400 BLM/ID/GI-15/006+1220 Getting There The portal to the Byway is Tendoy, Idaho, which is nineteen miles south of Salmon on Idaho Highway 28. From Montana, exit from I-15 at Clark Canyon Reservoir south of Dillon onto Montana Highway 324. Drive west past Grant to an intersection at the Shoshone Ridge Overlook. If you’re pulling a trailer or driving an RV with a passenger vehicle in tow, it would be a good idea to leave your trailer or RV at the overlook, which has plenty of parking, a vault toilet, and interpretive signs. Travel road 3909 west 12 miles to Lemhi Pass. Please respect private property along the road and obey posted speed signs. Salmon, Idaho, and Dillon, Montana, are full- service communities. Limited services are available in Tendoy, Lemhi, and Leadore, Idaho and Grant, Montana. -

Yukon Butterflies a Guide to Yukon Butterflies

Wildlife Viewing Yukon butterflies A guide to Yukon butterflies Where to find them Currently, about 91 species of butterflies, representing five families, are known from Yukon, but scientists expect to discover more. Finding butterflies in Yukon is easy. Just look in any natural, open area on a warm, sunny day. Two excellent butterfly viewing spots are Keno Hill and the Blackstone Uplands. Pick up Yukon’s Wildlife Viewing Guide to find these and other wildlife viewing hotspots. Visitors follow an old mining road Viewing tips to explore the alpine on top of Keno Hill. This booklet will help you view and identify some of the more common butterflies, and a few distinctive but less common species. Additional species are mentioned but not illustrated. In some cases, © Government of Yukon 2019 you will need a detailed book, such as , ISBN 978-1-55362-862-2 The Butterflies of Canada to identify the exact species that you have seen. All photos by Crispin Guppy except as follows: In the Alpine (p.ii) Some Yukon butterflies, by Ryan Agar; Cerisy’s Sphynx moth (p.2) by Sara Nielsen; Anicia such as the large swallowtails, Checkerspot (p.2) by Bruce Bennett; swallowtails (p.3) by Bruce are bright to advertise their Bennett; Freija Fritillary (p.12) by Sonja Stange; Gallium Sphinx presence to mates. Others are caterpillar (p.19) by William Kleeden (www.yukonexplorer.com); coloured in dull earth tones Butterfly hike at Keno (p.21) by Peter Long; Alpine Interpretive that allow them to hide from bird Centre (p.22) by Bruce Bennett.