The Downfall of Daesh in the Middle East and Implications for Global Security

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Global Extremism Monitor

Global Extremism Monitor Violent Islamist Extremism in 2017 WITH A FOREWORD BY TONY BLAIR SEPTEMBER 2018 1 2 Contents Foreword 7 Executive Summary 9 Key Findings About the Global Extremism Monitor The Way Forward Introduction 13 A Unifying Ideology Global Extremism Today The Long War Against Extremism A Plethora of Insurgencies Before 9/11 A Proliferation of Terrorism Since 9/11 The Scale of the Problem The Ten Deadliest Countries 23 Syria Iraq Afghanistan Somalia Nigeria Yemen Egypt Pakistan Libya Mali Civilians as Intended Targets 45 Extremist Groups and the Public Space Prominent Victims Breakdown of Public Targets Suicide Bombings 59 Use of Suicide Attacks by Group Female Suicide Bombers Executions 71 Deadliest Groups Accusations Appendices 83 Methodology Glossary About Us Notes 3 Countries Affected by Violent Islamist Extremism, 2017 4 5 6 Foreword Tony Blair One of the core objectives of the Institute is the promotion of co-existence across the boundaries of religious faith and the combating of extremism based on an abuse of faith. Part of this work is research into the phenomenon of extremism derived particularly from the abuse of Islam. This publication is the most comprehensive analysis of such extremism to date and utilises data on terrorism in a new way to show: 1. Violent extremism connected with the perversion of Islam today is global, affecting over 60 countries. 2. Now more than 120 different groups worldwide are actively engaged in this violence. 3. These groups are united by an ideology that shares certain traits and beliefs. 4. The ideology and the violence associated with it have been growing over a period of decades stretching back to the 1980s or further, closely correlated with the development of the Muslim Brotherhood into a global movement, the Iranian Revolution in 1979 and—in the same year—the storming by extremist insurgents of Islam’s holy city of Mecca. -

Terrorist Situation Outside the EU33

TESAT 2018 34 Terrorist situation outside the EU33 33 This section is largely based on open sources. Members of Albanian, Bosnian and regarded a viable terrorist threat. Roma minority communities are The same applies to jihadist groups predominant in jihadist groups in in the country, although some of Serbia. The country also reported their members, in particular returned propaganda activities being recorded FTFs, possess knowledge and skills in 2017, both through personal that could be used for terrorist contacts in informal religious groups, purposes. Moderate groups oppose from some informal religious venues violent methods and seek to distance as well as via the internet and social themselves from radical elements in networks. These propaganda activities their midst. were aimed at the radicalisation and Bosnia and Herzegovina asserts that recruitment of new members for up to December 2017 approximately terrorist organisations. Increasingly Western Balkan 300 persons had travelled from the women are being approached, as well country to Iraq and Syria. As per 31 as members of the Roma population. countries December 2017 an estimated 107 were Spouses of radical Islamists are found still in Syria, of whom 61 men and to be very active in recruiting other 46 women. It is believed that by that None of the Western Balkan countries women. date 41 FTFs had returned to Bosnia have reported acts of jihadist terrorism However, in 2017 there was a and Herzegovina and that 71 FTFs having taken place in their territories significant decline in activities aimed had lost their lives. In 2017 only one in 2017. Kosovo34 reported a decline at recruiting persons for terrorist (failed) attempt has been recorded of in jihadist propaganda activities and organisations in Iraq and Syria. -

Counter Terrorist Trends and Analyses ISSN 2382-6444 | Volume 9, Issue 5 | May 2017

Counter Terrorist Trends and Analyses www.rsis.edu.sg ISSN 2382-6444 | Volume 9, Issue 5 | May 2017 A JOURNAL OF THE INTERNATIONAL CENTRE FOR POLITICAL VIOLENCE AND TERRORISM RESEARCH The Islamic State’s Northward Expansion in the Philippines Rohan Gunaratna The Revival of Al Qaeda’s Affiliate in Southeast Asia: the Jemaah Islamiyah Bilveer Singh IS Footprint in Pakistan: Nature of Presence, Method of Recruitment, and Future Outlook Farhan Zahid Islamic State’s Financing: Sources, Methods and Utilisation Patrick Blannin The Islamic State in India: Exploring its Footprints Mohammed Sinan Siyech Counter Terrorist Trends and Analyses Volume 9, Issue 4 | April 2017 1 Building a Global Network for Security Editorial Note The Islamic State (IS) terrorist group that (AQ) return to the top of the jihadi pyramid and emerged victorious in Iraq in 2014 has lost its merger between the two old jihadi allies. Iraqi eminence. Presently, it is on the defensive, Vice President Ayad Allawi recently stated that struggling to retain its strongholds in Iraq and ‘discussions and dialogue’ have been taking Syria. This contrasts with the situation in 2014 place between Abu Bakr Al Baghdadi’s when the group was on the rise. It was representatives and AQ chief Ayman Al expanding territorially, producing shockingly Zawahiri. Any rapprochement between the two brutal videos with cinematic flare, and rivals is likely to further complicate the jihadi proclaiming its revival of the so-called landscape in Iraq, Syria and beyond. ‘caliphate’ and implementation of Sharia to beguile local and foreign Muslims and fellow Against this backdrop, the latest issue of CTTA jihadists. -

PERSONS • of the YEAR • Muslimthe 500 the WORLD’S 500 MOST INFLUENTIAL MUSLIMS • 2018 •

PERSONS • OF THE YEAR • MuslimThe 500 THE WORLD’S 500 MOST INFLUENTIAL MUSLIMS • 2018 • MuslimThe 500 THE WORLD’S 500 MOST INFLUENTIAL MUSLIMS • 2018 • C The Muslim 500: 2018 Chief Editor: Prof S Abdallah Schleifer The World’s 500 Most Influential Muslims, 2018 Deputy Chief Editor: Ms Farah El-Sharif ISBN: 978-9957-635-14-5 Contributing Editor: Dr Tarek Elgawhary Editor-at-Large: Mr Aftab Ahmed Jordan National Library Deposit No: 2017/10/5597 Editorial Board: Dr Minwer Al-Meheid, Mr Moustafa Elqabbany, and Ms Zeinab Asfour © 2017 The Royal Islamic Strategic Studies Centre 20 Sa’ed Bino Road, Dabuq Researchers: Lamya Al-Khraisha, Moustafa Elqabbany, PO BOX 950361 Zeinab Asfour, and M AbdulJaleal Nasreddin Amman 11195, JORDAN http://www.rissc.jo Consultant: Simon Hart All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced Typeset by: M AbdulJaleal Nasreddin or utilized in any form or by any means, electronic or me- chanic, including photocopying or recording or by any in- formation storage and retrieval system, without the prior written permission of the publisher. Views expressed in The Muslim 500 do not necessarily re- flect those of RISSC or its advisory board. Set in Garamond Premiere Pro Printed in The Hashemite Kingdom of Jordan Calligraphy used throughout the book provided courtesy of www.FreeIslamicCalligraphy.com Title page Bismilla by Mothana Al-Obaydi • Contents • page 1 Introduction 5 Persons of the Year—2018 7 Influence and The Muslim 500 9 The House of Islam 21 The Top 50 89 Honourable Mentions 97 The 450 Lists 99 Scholarly -

ISIS Khorasan: Presence, Affiliations and Regional Alliances with Russia

WALIA journal 35(1): 70-76, 2019 Available online at www.Waliaj.com ISSN 1026-3861 © 2019 WALIA ISIS Khorasan: Presence, affiliations and regional alliances with Russia Muhammad Amin *, Muhammad Asif University of Balochistan, Quetta, Pakistan Abstract: The eco-political instability of the Middle East gave birth to ISIS. It made the Middle Eastern region destabilized. ISIS has a large number of fighters from other regions of the world. Some of them belong to Pakistan, China, Afghanistan, Russia and Central Asia. The growth and revenue of ISIS influenced the Taliban and Al-Qaeda splinters to announce an affiliation with ISIS. It announced ISIS Wilayat Khorasan with the help of these splinters. The affiliates of ISIS Khorasan are attacking and killing many people of Pakistan and Afghanistan are being attacked by ISIS Khorasan. It also wants to spread its growth and launch attacks in other countries of this region. Russia, China and Pakistan want to form an alliance against ISIS. Therefore, they are organizing regular meetings on the issue. The entry of ISIS Khorasan in the region demands from the regional countries a comprehensive strategy to counter ISIS Khorasan. The analytical method has been used for this study and most of the data have been taken from secondary sources. It is argued that the threat of ISIS Khorasan is compelling the regional powers to have an alliance with Russia against ISIS. Key words: Region; Affiliates; Wilayat Khorasan; Alliance; Attack 1. Introduction 2. Islamic state of Iraq and Syria *Asia is the home of 106 billion Muslims which Abu Musab al-Zarqawi founded a militant group covers, 62% of the world population. -

ISIS Type of Organization

ISIS Name: ISIS Type of Organization: Insurgent territory-controlling religious terrorist violent Ideologies and Affiliations: Islamist jihadist pan-Islamist Salafist takfiri Place of Origin: Iraq Year of Origin: Al-Qaeda in Iraq: 2004; ISIS: 2013 Founder(s): Al-Qaeda in Iraq: Abu Musab al-Zarqawi; ISIS: Abu Bakr al-Baghdadi Places of Operation: ISIS has declared wilayas (provinces) in Iraq, Syria, Egypt, Libya, Algeria, Yemen, Saudi Arabia, Nigeria, Afghanistan, Pakistan, India, Turkey, Central Africa, Mali, Niger, Democratic Republic of the Congo, Mozambique, and the North Caucasus. Beyond this, the terror group has waged attacks in Lebanon, France, Belgium, Bangladesh, Morocco, Indonesia, Malaysia, Tunisia, and Kuwait. Overview Also known as: ISIS Al-Qa’ida Group of Jihad in Iraq1 Organization of al-Jihad’s Base in the Land of the Two Rivers40 Al-Qa’ida Group of Jihad in the Land of the Two Rivers2 Organization Base of Jihad/Country of the Two Rivers41 Al-Qaeda in Iraq (AQI)3 Organization of al-Jihad’s Base of Operations in Iraq42 Al-Qa’ida in Iraq – Zarqawi4 Organization of al-Jihad’s Base of Operations in the Land of the Al-Qaeda in Mesopotamia (AQM)5 Two Rivers43 Al-Qa’ida in the Land of the Two Rivers6 Organization of Jihad’s Base in the Country of the Two Rivers Al-Qa’ida of Jihad Organization in the Land of the Two Rivers7 44 Al-Qa’ida of the Jihad in the Land of the Two Rivers8 Qaida of the Jihad in the Land of the Two Rivers45 Al-Qaeda Separatists in Iraq and Syria (QSIS)9 Southern Province46 Al-Tawhid10 Tanzeem Qa'idat al -

A Theory of ISIS

A Theory of ISIS A Theory of ISIS Political Violence and the Transformation of the Global Order Mohammad-Mahmoud Ould Mohamedou First published 2018 by Pluto Press 345 Archway Road, London N6 5AA www.plutobooks.com Copyright © Mohammad-Mahmoud Ould Mohamedou 2018 The right of Mohammad-Mahmoud Ould Mohamedou to be identified as the author of this work has been asserted by him in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988. British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library ISBN 978 0 7453 9911 9 Hardback ISBN 978 0 7453 9909 6 Paperback ISBN 978 1 7868 0169 2 PDF eBook ISBN 978 1 7868 0171 5 Kindle eBook ISBN 978 1 7868 0170 8 EPUB eBook This book is printed on paper suitable for recycling and made from fully managed and sustained forest sources. Logging, pulping and manufacturing processes are expected to conform to the environmental standards of the country of origin. Typeset by Stanford DTP Services, Northampton, England Simultaneously printed in the United Kingdom and United States of America Contents List of Figures vii List of Tables viii List of Abbreviations ix Acknowledgements x Introduction: The Islamic State and Political Violence in the Early Twenty-First Century 1 Misunderstanding IS 6 Genealogies of New Violence 22 Theorising IS 28 1. Al Qaeda’s Matrix 31 Unleashing Transnational Violence 32 Revenge of the ‘Agitated Muslims’ 49 The McDonaldisation of Terrorism 57 2. Apocalypse Iraq 65 Colonialism Redesigned 66 Monstering in American Iraq 74 ‘I will see you in New York’ 83 3. -

Introduction 1 What Is Sufism? History, Characteristics, Patronage

Notes Introduction 1 . It must be noted that even if Sufism does indeed offer a positive mes- sage, this does not mean that non-Sufi Muslims, within this dichotomous framework, do not also offer similar positive messages. 2. We must also keep in mind that it is not merely current regimes that can practice illiberal democracy but also Islamist governments, which may be doing so for power, or based on their specific stance of how Islam should be implemented in society (Hamid, 2014: 25–26). 3 . L o i m e i e r ( 2 0 0 7 : 6 2 ) . 4 . Often, even cases that looked to be solely political actually had specific economic interests underlying the motivation. For example, Loimeier (2007) argues that in the cases of Sufi sheikhs such as Ahmad Khalifa Niass (b. 1946), along with Sidi Lamine Niass (b. 1951), both first seemed to speak out against colonialism. However, their actions have now “be[en] interpreted as particularly clever strategies of negotiating privileged posi- tions and access to scarce resources in a nationwide competition for state recognition as islamologues fonctionnaries ” (Loimeier, 2007: 66–67). 5 . There have been occasions on which the system was challenged, but this often occurred when goods or promises were not granted. For example, Loimeier (2007: 63) explains that the times when the relationship seemed to be questioned were times when the state was having economic issues and often could not provide the benefits people expected. When this happened, Murid Sufi leaders at times did speak out against the state’s authority (64). -

Six Years of War in Syria Political and Humanitarian Aspect

SIX YEARS OF WAR IN SYRIA POLITICAL AND HUMANITARIAN ASPECT NR: 005 MAY 2017 RESEARCH CENTRE RESEARCH CENTRE © TRT WORLD RESEARCH CENTRE ALL RIGHTS RESERVED PUBLISHER TRT WORLD CONTRIBUTORS PINAR KANDEMIR RESUL SERDAR ATAS AHMED AL BURAI OZAN AHMET CETIN MUHAMMED LUTFI TURKCAN RAZAN SAFFOUR ALPASLAN OGUZ AHMET FURKAN GUNGOREN MUHAMMED MASUK YILDIZ ESREF YALINKILICLI ACHMENT GONIM ALONSO ALVAREZ COVER PHOTO BURCU OZER / ANADOLU AGENCY (AA) TRT WORLD ISTANBUL AHMET ADNAN SAYGUN STREET NO:83 34347 ULUS, BESIKTAS ISTANBUL / TURKEY www.trtworld.com TRT WORLD LONDON PORTLAND HOUSE 4 GREAT PORTLAND STREET NO:4 LONDON / UNITED KINGDOM www.trtworld.com TRT WORLD WASHINGTON D.C. 1620 I STREET NW, 10TH FLOOR, SUITE 1000 WASHINGTON DC, 20006 www.trtworld.com Content 07 INTRODUCTION 08 RUN UP TO THE WAR IN SYRIA 21 POLITICAL ASPECT: SYRIA POLICIES OF INTERNATIONAL AND LOCAL ACTORS 22 INTERNATIONAL ORGANIZATIONS 23 THE UNITED NATIONS 30 THE EUROPEAN UNION 34 THE LEAGUE OF ARAB STATES 35 STATES 36 TURKEY 43 THE UNITED STATES 50 RUSSIA 57 IRAN 61 SAUDI ARABIA 64 CHINA 66 NON-STATE ACTORS 67 SYRIAN POLITICAL OPPOSITION 73 DAESH 76 PKK’S SYRIA OFFSHOOT: PYD-YPG 80 HEZBOLLAH 83 HUMANITARIAN ASPECT 88 HUMAN RIGHTS VIOLATIONS 96 INTERNALLY DISPLACED SYRIANS 98 REFUGEES IN TURKEY 106 REFUEGES IN JORDAN 108 REFUGEES IN LEBANON 110 REFUGEES IN THE EU 116 CONCLUSION: SHOCKWAVES OF THE SYRIAN WAR 120 ENDNOTES TRT World 6 Research Centre TRT World Research Centre 7 Introduction At TRT World, we aim to do things differently. Since missed opportunities to restore stability in the war- we started the TRT World on 27 October 2015, we torn country. -

Pakistan's New War on Terror

Pakistan’s new war on terror Why in news? \n\n Recently Inter Services Public Relations, media wing of the Pakistan Armed Forces, announced the launch of Operation Radd-ul-Fasaad against terrorists across the country. \n\n What is Radd-ul-Fasaad? \n\n \n The latest in a string of Pakistani counter-terrorism operations, directed at dismantling jihadist infrastructure within the country. \n It marks an official acceptance of the well-known fact that terrorists are active in Northern Sindh and Punjab, and that there’s a need to act against them if terrorism in the country is to be defeated. \n \n\n How is it different in tactically from the earlier operation, Zarb-e-Azb? \n\n \n Zarb-e-Azb focussed on massive force operations against the Tehreek-e- Taliban Pakistan and other jihadist groups in one region, North Waziristan (Federally Administered Tribal Areas) following the attack on Karachi’s Jinnah International Airport in June 2014. \n Radd-ul-Fasaad is nationwide, and doesn’t seem to involve conventional military operations. \n Zarb-e-Azb has not been called off officially yet. \n But the Pak Army claims it has eliminated terrorists from all but a tiny sliver of North Waziristan. \n \n\n \n\n How successful was Zarb-e-Azb? \n\n \n It’s hard to say since the only source of information is the Pak Army, which claims several thousand terrorists have been killed. \n In strategic terms, though, it’s clearly been a failure, as the TTP and other terror groups are relocating their infrastructure across the border into Afghanistan. -

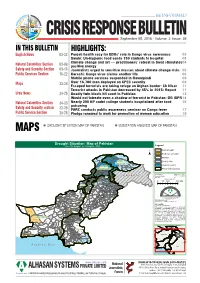

Crisis Response Bulletin

IDP IDP IDP CRISIS RESPONSE BULLETIN September 05, 2016 - Volume: 2, Issue: 36 IN THIS BULLETIN HIGHLIGHTS: English News 03-22 Punjab health secy for EDOs’ role in Congo virus awareness 03 Swabi: Un-hygienic food sends 150 students to hospital 03 Climate change and art — practitioners’ retreat in Swat stimulates04 Natural Calamities Section 03-08 positive energy Safety and Security Section 09-15 Journalists urged to sensitise masses about climate change risks 05 Public Services Section 16-22 Karachi: Congo virus claims another life 06 Mobile phone services suspended in Rawalpindi 09 Maps 23-24 Over 16,700 men deployed on CPEC security 09 Escaped terrorists are taking refuge on Afghan border: Ch Nisar 11 Terrorist attacks in Pakistan decreased by 45% in 2015: Report 11 Urdu News 34-25 Deadly twin blasts hit court in Pakistan 13 Would not tolerate even a shadow of terrorist in Pakistan: DG ISPR14 Natural Calamities Section 34-33 Nearly 200 KP cadet college students hospitalized after food 16 poisoning Safety and Security section 32-29 PARC conducts public awareness seminar on Congo fever 17 Public Service Section 28-25 Pledge renewed to work for promotion of women education 19 MAPS DROUGHT SITUATION MAP OF PAKISTAN VEGETATION ANALYSIS MAP OF PAKISTAN Drought Situation Map of Pakistan As of 16 August to 31 August , 2016 Legend Mild Drought ¯ Moderate Drought GOJAL ISHKOMEN YASIN MASTUJ NAGAR-II ALIABAD Normal NAGAR-I GUPIS PUNIAL CHITRAL GILGIT GILGIT DAREL Slightly Wet TANGIR SHIGAR BAHRAIN KANDIA BALTISTAN SHARINGAL PATTAN CHILAS MASHABRUM -

Crisis Response Bulletin Page 1-16

IDP IDP IDP CRISIS RESPONSE BULLETIN November 07, 2016 - Volume: 2, Issue: 45 IN THIS BULLETIN HIGHLIGHTS: English News 03-24 2,000 dengue fever cases surfaced in Sindh this year 03 Beijing to build ventilation corridors as smog returns 04 Pakistan Climate Change Council to be formed soon 05 Natural Calamities Section 03-07 Smog to stay for two months, says DG Met 05 Safety and Security Section 08-20 Safer, resilient communities: ‘Youth in need of disaster 06 Public Services Section 21-24 management training’ China stands by Pakistan meeting its defense requirements, says 08 Maps 25-26 Chang Wanquan Mastermind of Quetta police academy carnage arrested 08 COAS confirms death sentences of nine hardcore terrorists 10 Urdu News 36-27 In Islamabad, funeral of National Action Plan held 11 National security above all and of foremost importance: Governor 15 Natural Calamities Section 36-35 Economy, security on stake again 17 GCUF 1894 students declared eligible for laptops 21 Safety and Security section 34-30 CPLC report shows mobile snatching trend continues in Karachi 22 Public Service Section 29-27 Pakistani scholars urged to apply for UK's Chevening Scholarships 22 MAPS DROUGHT SITUATION MAP - PAKISTAN VEGETATION ANALYSIS MAP OF PAKISTAN Drought Situation Map of Pakistan As of 15 October to 31 October, 2016 Legend Mild Drought ¯ Moderate Drought GOJAL ISHKOMEN YASIN MASTUJ NAGAR-II ALIABAD Normal NAGAR-I GUPIS PUNIAL CHITRAL GILGIT GILGIT DAREL Slightly Wet TANGIR SHIGAR BAHRAIN KANDIA BALTISTAN SHARINGAL PATTAN CHILAS MASHABRUM Moderately