THE MASS of KOI-94D and a RELATION for PLANET RADIUS, MASS, and INCIDENT FLUX∗

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

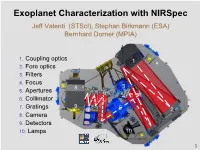

Exoplanet Characterization with Nirspec

Exoplanet Characterization with NIRSpec Jeff Valenti (STScI), Stephan Birkmann (ESA) Bernhard Dorner (MPIA) 1. Coupling optics 1 2. Fore optics 3. Filters 4. Focus 8 3 5. Apertures 6 4 6. Collimator 9 7. Gratings 7 5 2 8. Camera 9. Detectors 10. Lamps 10 1 NIRSpec Apertures Aperture Spectral Spatial S1600 1.6” 1.6” S400 0.4” 3.65” S200 0.2” 3.2” IFU 36 x 0.1” 3.6” MSA 2 x 95” 2 x 87” The S1600 aperture was designed for exoplanet observations 2 Noise Due to Jitter 1σ Jitter Jitter of 7 mas causes relative noise of 4 x 10-5 From PhD thesis Bernhard Dorner 3 NIRSpec Optical Configurations Grating Filter Wavelengths Resolution PRISM CLEAR 0.6 – 5.0 30 – 300 “100” F070LP 0.7 – 1.2 500 – 850 G140M F100LP 1.0 – 1.8 “1000” G235M F170LP 1.7 – 3.0 700 – 1300 G395M F290LP 2.9 – 5.0 F070LP 0.7 – 1.2 1300 – 2300 G140H F100LP 1.0 – 1.8 “2700” G235H F170LP 1.7 – 3.0 1900 – 3600 G395H F290LP 2.9 – 5.0 4 http://www.cosmos.esa.int/web/jwst/nirspec-performances 5 6 http://www.cosmos.esa.int/web/jwst/nirspec-performances Example of High-Resolution Model Spectra G395H Figure 4b of Burrows, Budaj, & Hubeny (2008) 7 Thermal Emission from a Hot Jupiter Adapted from Figure 4b of Burrows, Budaj, & Hubeny (2008) 8 Integrations and Exposures " An “exposure” is a sequence of integrations. " An “integration” is a sequence of groups, sampled up-the-ramp " One or more resets between integrations, but no other overheads " Currently using pixel-by-pixel resets, but row-by-row possible 9 Subarrays NX NY Frame time (s) Notes 2048 512 10.74 Full frame, 4 amps 2048 256 5.49 -

ON the INCLINATION DEPENDENCE of EXOPLANET PHASE SIGNATURES Stephen R

The Astrophysical Journal, 729:74 (6pp), 2011 March 1 doi:10.1088/0004-637X/729/1/74 C 2011. The American Astronomical Society. All rights reserved. Printed in the U.S.A. ON THE INCLINATION DEPENDENCE OF EXOPLANET PHASE SIGNATURES Stephen R. Kane and Dawn M. Gelino NASA Exoplanet Science Institute, Caltech, MS 100-22, 770 South Wilson Avenue, Pasadena, CA 91125, USA; [email protected] Received 2011 December 2; accepted 2011 January 5; published 2011 February 10 ABSTRACT Improved photometric sensitivity from space-based telescopes has enabled the detection of phase variations for a small sample of hot Jupiters. However, exoplanets in highly eccentric orbits present unique opportunities to study the effects of drastically changing incident flux on the upper atmospheres of giant planets. Here we expand upon previous studies of phase functions for these planets at optical wavelengths by investigating the effects of orbital inclination on the flux ratio as it interacts with the other effects induced by orbital eccentricity. We determine optimal orbital inclinations for maximum flux ratios and combine these calculations with those of projected separation for application to coronagraphic observations. These are applied to several of the known exoplanets which may serve as potential targets in current and future coronagraph experiments. Key words: planetary systems – techniques: photometric 1. INTRODUCTION and inclination for a given eccentricity. We further calculate projected separations at apastron as a function of inclination The changing phases of an exoplanet as it orbits the host star and determine their correspondence with maximum flux ratio have long been considered as a means for their detection and locations. -

IAU Division C Working Group on Star Names 2019 Annual Report

IAU Division C Working Group on Star Names 2019 Annual Report Eric Mamajek (chair, USA) WG Members: Juan Antonio Belmote Avilés (Spain), Sze-leung Cheung (Thailand), Beatriz García (Argentina), Steven Gullberg (USA), Duane Hamacher (Australia), Susanne M. Hoffmann (Germany), Alejandro López (Argentina), Javier Mejuto (Honduras), Thierry Montmerle (France), Jay Pasachoff (USA), Ian Ridpath (UK), Clive Ruggles (UK), B.S. Shylaja (India), Robert van Gent (Netherlands), Hitoshi Yamaoka (Japan) WG Associates: Danielle Adams (USA), Yunli Shi (China), Doris Vickers (Austria) WGSN Website: https://www.iau.org/science/scientific_bodies/working_groups/280/ WGSN Email: [email protected] The Working Group on Star Names (WGSN) consists of an international group of astronomers with expertise in stellar astronomy, astronomical history, and cultural astronomy who research and catalog proper names for stars for use by the international astronomical community, and also to aid the recognition and preservation of intangible astronomical heritage. The Terms of Reference and membership for WG Star Names (WGSN) are provided at the IAU website: https://www.iau.org/science/scientific_bodies/working_groups/280/. WGSN was re-proposed to Division C and was approved in April 2019 as a functional WG whose scope extends beyond the normal 3-year cycle of IAU working groups. The WGSN was specifically called out on p. 22 of IAU Strategic Plan 2020-2030: “The IAU serves as the internationally recognised authority for assigning designations to celestial bodies and their surface features. To do so, the IAU has a number of Working Groups on various topics, most notably on the nomenclature of small bodies in the Solar System and planetary systems under Division F and on Star Names under Division C.” WGSN continues its long term activity of researching cultural astronomy literature for star names, and researching etymologies with the goal of adding this information to the WGSN’s online materials. -

Exoplanet Detection Techniques

Exoplanet Detection Techniques Debra A. Fischer1, Andrew W. Howard2, Greg P. Laughlin3, Bruce Macintosh4, Suvrath Mahadevan5;6, Johannes Sahlmann7, Jennifer C. Yee8 We are still in the early days of exoplanet discovery. Astronomers are beginning to model the atmospheres and interiors of exoplanets and have developed a deeper understanding of processes of planet formation and evolution. However, we have yet to map out the full complexity of multi-planet architectures or to detect Earth analogues around nearby stars. Reaching these ambitious goals will require further improvements in instru- mentation and new analysis tools. In this chapter, we provide an overview of five observational techniques that are currently employed in the detection of exoplanets: optical and IR Doppler measurements, transit pho- tometry, direct imaging, microlensing, and astrometry. We provide a basic description of how each of these techniques works and discuss forefront developments that will result in new discoveries. We also highlight the observational limitations and synergies of each method and their connections to future space missions. Subject headings: 1. Introduction tary; in practice, they are not generally applied to the same sample of stars, so our detection of exoplanet architectures Humans have long wondered whether other solar sys- has been piecemeal. The explored parameter space of ex- tems exist around the billions of stars in our galaxy. In the oplanet systems is a patchwork quilt that still has several past two decades, we have progressed from a sample of one missing squares. to a collection of hundreds of exoplanetary systems. Instead of an orderly solar nebula model, we now realize that chaos 2. -

Exoplanetary Geophysics--An Emerging Discipline

Invited Review for Treatise on Geophysics, 2nd Edition Exoplanetary Geophysics { An Emerging Discipline Gregory Laughlin UCO/Lick Observatory, University of California, Santa Cruz, Santa Cruz, CA 95064, USA Jack J. Lissauer NASA Ames Research Center, Planetary Systems Branch, Moffett Field, CA 94035, USA 1. Abstract Thousands of extrasolar planets have been discovered, and it is clear that the galactic planetary census draws on a diversity greatly exceeding that exhibited by the solar system's planets. We review significant landmarks in the chronology of extrasolar planet detection, and we give an overview of the varied observational techniques that are brought to bear. We then discuss the properties of the planetary distribution that is currently known, using the mass-period diagram as a guide to delineating hot Jupiters, eccentric giant planets, and a third, highly populous, category that we term \ungiants", planets having masses M < 30 M⊕ and orbital periods P < 100 d. We then move to a discussion of the bulk compositions of the extrasolar planets, with particular attention given to the distribution of planetary densities. We discuss the long-standing problem of radius anomalies among giant planets, as well as issues posed by the unexpectedly large range in sizes observed for planets with mass somewhat greater than Earth's. We discuss the use of transit observations to probe the atmospheres of extrasolar planets; various measurements taken during primary transit, secondary eclipse, and through the full orbital period, can give clues to the atmospheric compositions, structures and meteorologies. The extrasolar planet catalog, along with the details of our solar system and observations of star-forming regions and protoplanetary disks, arXiv:1501.05685v1 [astro-ph.EP] 22 Jan 2015 provide a backdrop for a discussion of planet formation in which we review the elements of the favored pictures for how the terrestrial and giant planets were assembled. -

Characterization of the HD 17156 Planetary System�,

A&A 503, 601–612 (2009) Astronomy DOI: 10.1051/0004-6361/200811466 & c ESO 2009 Astrophysics Characterization of the HD 17156 planetary system, M. Barbieri1, R. Alonso1,S.Desidera2, A. Sozzetti3, A. F. Martinez Fiorenzano4,J.M.Almenara5, M. Cecconi4, R. U. Claudi2, D. Charbonneau7 ,M.Endl8, V. Granata2,9, R. Gratton2,G.Laughlin10, B. Loeillet1,6, and Exoplanet Amateur Consortium 1 Laboratoire d’Astrophysique de Marseille, 38 rue Joliot-Curie, 13388 Marseille Cedex 13, France e-mail: [email protected] 2 INAF Osservatorio Astronomico di Padova, Vicolo dell’ Osservatorio 5, 35122 Padova, Italy 3 INAF Osservatorio Astronomico di Torino, 10025 Pino Torinese, Italy 4 Fundación Galileo Galilei – INAF, Rambla José Ana Fernández Pérez 7, 38712 Breña Baja (TF), Spain 5 Instituto de Astrofísica de Canarias, C/Vía Láctea s/n, 38200 La Laguna, Spain 6 IAP, 98bis Bd Arago, 75014 Paris, France 7 Harvard-Smithsonian Center for Astrophysics, 60 Garden Street, Cambridge, MA 02138, USA 8 McDonald Observatory, The University of Texas at Austin, Austin, TX 78712, USA 9 CISAS, Università di Padova, Italy 10 University of California Observatories, University of California at Santa Cruz Santa Cruz, CA 95064, USA Received 2 December 2008 / Accepted 12 March 2009 ABSTRACT Aims. We present data to improve the known parameters of the HD 17156 system (peculiar due to the eccentricity and long orbital period of its transiting planet) and constrain the presence of stellar companions. Methods. Photometric data were acquired for 4 transits, and high precision radial velocity measurements were simultaneously acquired with the SARG spectrograph at TNG for one transit. -

Mass-Loss Rates for Transiting Exoplanets Energy Diagram Enable to Estimate the Observable Transit Signa- Ture of Evaporating Planets (E.G., Ehrenreich Et Al

Astronomy & Astrophysics manuscript no. massloss˙vA1 c ESO 2018 November 2, 2018 Mass-loss rates for transiting exoplanets D. Ehrenreich1 & J.-M. D´esert2 1 Institut de plan´etologie et d’astrophysique de Grenoble (IPAG), Universit´eJoseph Fourier-Grenoble 1, CNRS (UMR 5274), BP 53 38041 Grenoble CEDEX 9, France, e-mail: [email protected] 2 Harvard-Smithsonian Center for Astrophysics, 60 Garden street, Cambridge, Massachusetts 02138, USA, e-mail: [email protected] ABSTRACT Exoplanets at small orbital distances from their host stars are submitted to intense levels of energetic radiations, X-rays and extreme ultraviolet (EUV). Depending on the masses and densities of the planets and on the atmospheric heating efficiencies, the stellar energetic inputs can lead to atmospheric mass loss. These evaporation processes are observable in the ultraviolet during planetary transits. The aim of the present work is to quantify the mass-loss rates (m ˙ ), heating efficiencies (η), and lifetimes for the whole sample of transiting exoplanets, now including hot jupiters, hot neptunes, and hot super-earths. The mass-loss rates and lifetimes are estimated from an “energy diagram” for exoplanets, which compares the planet gravitational potential energy to the stellar X/EUV energy deposited in the atmosphere. We estimate the mass-loss rates of all detected transiting planets to be within 106 to 1013 g s−1 for various conservative assumptions. High heating efficiencies would imply that hot exoplanets such the gas giants WASP-12b and WASP-17b could be completely evaporated within 1 Gyr. We further show that the heating efficiency can be constrained whenm ˙ is inferred from observations and the stellar X/EUV luminosity is known. -

Planetary Transits and Tidal Evolution

Transiting Planets Proceedings IAU Symposium No. 253, 2008 c 2008 International Astronomical Union DOI: 00.0000/X000000000000000X Planetary Transits and Tidal Evolution Brian Jackson1, Rory Barnes1, and Richard Greenberg1 1Lunar and Planetary Laboratory, University of Arizona 1629 E University Blvd, Tucson AZ 85721-0092 USA email: [email protected] Abstract. Transiting planets are generally close enough to their host stars that tides may govern their orbital and thermal evolution of these planets. We present calculations of the tidal evolution of recently discovered transiting planets and discuss their implications. The tidal heating that accompanies this orbital evolution can be so great that it controls the planet’s physical properties and may explain the large radii observed in several cases, including, for example, TrES-4. Also because a planet’s transit probability depends on its orbit, it evolves due to tides. Current values depend sensitively on the physical properties of the star and planet, as well as on the system’s age. As a result, tidal effects may introduce observational biases in transit surveys, which may already be evident in current observations. Transiting planets tend to be younger than non-transiting planets, an indication that tidal evolution may have destroyed many close-in planets. Also the distribution of the masses of transiting planets may constrain the orbital inclinations of non-transiting planets. Keywords. (stars:) planetary systems: formation 1. Introduction Most close-in planets, and thus most transiting planets, have likely undergone sig- nificant evolution of their orbits since the planets formed and the gas disks dissipated. Jackson et al. (2008a) showed that the initial eccentricities of close-in planets were likely distributed in value similarly to the eccentricities of planets far from their host stars. -

Radial Velocity Transit Animation by European Southern Observatory Animation by NASA Goddard Media Studios

Courtney Dressing Assistant Professor at UC Berkeley The Space Astrophysics Landscape for the 2020s and Beyond April 1, 2019 Credit: NASA David Charbonneau (Co-Chair), Scott Gaudi (Co-Chair), Fabienne Bastien, Jacob Bean, Justin Crepp, Eliza Kempton, Chryssa Kouveliotou, Bruce Macintosh, Dimitri Mawet, Victoria Meadows, Ruth Murray-Clay, Evgenya Shkolnik, Ignas Snellen, Alycia Weinberger Exoplanet Discoveries Have Increased Dramatically Figure Credit: A. Weinberger (ESS Report) What Do We Know Today? (Statements from the ESS Report) • “Planetary systems are ubiquitous and surprisingly diverse, and many bear no resemblance to the Solar System.” • “A significant fraction of planets appear to have undergone large-scale migration from their birthsites.” • “Most stars have planets, and small planets are abundant.” • “Large numbers of rocky planets [have] been identified and a few habitable zone examples orbiting nearby small stars have been found.” • “Massive young Jovians at large separations have been imaged.” • “Molecules and clouds in the atmospheres of large exoplanets have been detected.” • ”The identification of potential false positives and negatives for atmospheric biosignatures has improved the biosignature observing strategy and interpretation framework.” Radial Velocity Transit Animation by European Southern Observatory Animation by NASA Goddard Media Studios How Did We Learn Those Lessons? Astrometry Direct Imaging Microlensing Animation by Exoplanet Exploration Office at NASA JPL Animation by Jason Wang Animation by Exoplanet Exploration Office at NASA JPL Exoplanet Science in the 2020s & Beyond The ESS Report Identified Two Goals 1. “Understand the formation and evolution of planetary systems as products of the process of star formation, and characterize and explain the diversity of planetary system architectures, planetary compositions, and planetary environments produced by these processes.” 2. -

How to Size an Exoplanet? a Model Approach for Visualization Akos Kereszturi* Research Center for Astronomy and Earth Sciences, Hungary

obiolog str y & f A O u o l t a r Kereszturi, Astrobiol Outreach 2013, 1:1 e n a r c u h o J Journal of Astrobiology & Outreach DOI: 10.4172/2332-2519.1000101 ISSN: 2332-2519 Research Article Article OpenOpen Access Access How to Size an Exoplanet? A Model Approach for Visualization Akos Kereszturi* Research Center for Astronomy and Earth Sciences, Hungary Abstract The realization and experiences with a physical exoplanet model in the education and outreach are described. During the tests with students in the classroom and adults at public demonstrations, the following conclusions were drawn: in the visualization it is effective to connect and install together the models of planets inside and outside the Solar System, where hot Jupiter’s easily fit into the orbit of Mercury. The size of planets and orbital distance could be more effectively visualized with this method, using the Solar System as a context. The exoplanet model helps to expand the imagination of the audience on how does a planetary system look like, what is getting important as diverse views of explanatory systems emerging in recent years. This inexpensive model is useful in the education and outreach above all to make the audience more familiar with the parameters of exoplanets (here sizes, distances and partly masses), and it gives new input also for those persons who regularly read papers and news on exoplanets. Keywords: Solar system; Mercury; Jupiter; Exoplanets; Planet; classroom sessions, and two sessions in astronomy camps) with Astrobiology different groups and persons, altogether for 178 participants at these lectures. -

Is the Activity Level of HD 80606 Influenced by Its Eccentric Planet?

A&A 592, A143 (2016) Astronomy DOI: 10.1051/0004-6361/201628981 & c ESO 2016 Astrophysics Is the activity level of HD 80606 influenced by its eccentric planet? P. Figueira1, A. Santerne1, A. Suárez Mascareño2, J. Gomes da Silva1, L. Abe3, V. Zh. Adibekyan1, P. Bendjoya3, A. C. M. Correia4; 5, E. Delgado-Mena1, J. P. Faria1; 6, G. Hebrard7; 8, C. Lovis9, M. Oshagh10, J.-P. Rivet3, N. C. Santos1; 6, O. Suarez3, and A. A. Vidotto11 1 Instituto de Astrofísica e Ciências do Espaço, Universidade do Porto, CAUP, Rua das Estrelas, 4150-762 Porto, Portugal e-mail: [email protected] 2 Instituto de Astrofísica de Canarias, 38205 La Laguna, Tenerife, Spain 3 Laboratoire J.-L. Lagrange, Université de Nice Sophia-Antipolis, CNRS, Observatoire de la Cote d’Azur, 06304 Nice, France 4 CIDMA, Departamento de Física, Universidade de Aveiro, Campus de Santiago, 3810-193 Aveiro, Portugal 5 ASD, IMCCE-CNRS UMR8028, Observatoire de Paris, 77 Av. Denfert-Rochereau, 75014 Paris, France 6 Departamento de Física e Astronomia, Faculdade de Ciências, Universidade do Porto, 4099-002 Porto, Portugal 7 Institut d’Astrophysique de Paris, UMR7095 CNRS, Université Pierre & Marie Curie, 98bis boulevard Arago, 75014 Paris, France 8 Observatoire de Haute-Provence, CNRS, Université d’Aix-Marseille, 04870 Saint-Michel-l’Observatoire, France 9 Observatoire Astronomique de l’Université de Genève, 51 Ch. des Maillettes, – Sauverny – 1290 Versoix, Suisse 10 Institut für Astrophysik, Georg-August-Universität, Friedrich-Hund-Platz 1, 37077 Göttingen, Germany 11 School of Physics, Trinity College Dublin, The University of Dublin, Dublin-2, Ireland Received 23 May 2016 / Accepted 12 June 2016 ABSTRACT Aims. -

Giant Planets

Architecture and demographics of planetary systems Wednesday, March 6, 2013 Struve (1952) Wednesday, March 6, 2013 The demography of the planets that we detect is strongly affected by • detection methods • psychology of the observer Understanding planet demography requires multiple detection methods: • radial velocities • transits • gravitational lensing • direct imaging • astrometry Wednesday, March 6, 2013 Kepler • launch March 6 2009 • 0.95 meter mirror, 100 megapixel camera, 12 degree diameter field of view • monitor ~105 stars continuously over ~6 yr mission • 30 parts per million photometric precision Wednesday, March 6, 2013 fractional brightness dip: Jupiter 0.01 = 1% Earth 0.0001=0.01% Pál et al. (2008) 1% Wednesday, March 6, 2013 Wednesday, March 6, 2013 Wednesday, March 6, 2013 Gravitational lensing image source track the gravitational field from the lensing star: lensing mass Einstein ring - splits image into two - magnifies one image and demagnifies the other - if source, lens and observer are exactly in line the image appears as an Einstein ring currently about 20 planets have been detected by lensing Wednesday, March 6, 2013 Gravitational lensing source track the gravitational field from the lensing star: lensing mass Einstein ring - splits image into two - magnifies one image and demagnifies the other - if source, lens and observer are exactly in line the image appears as an Einstein ring currently about 20 planets have been detected by lensing Wednesday, March 6, 2013 transits radial velocities Wednesday, March 6, 2013 observational