Giant Planets

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Predicting Exoplanet Observability in Time, Contrast, Separation, and Polarization, in Scattered Light

A&A 578, A59 (2015) Astronomy DOI: 10.1051/0004-6361/201424202 & c ESO 2015 Astrophysics Predicting exoplanet observability in time, contrast, separation, and polarization, in scattered light Guillaume Schworer1;2 and Peter G. Tuthill2 1 LESIA, Observatoire de Paris, CNRS/UMR 8109, UPMC, Université Paris Diderot, 5 place J. Janssen, 92195 Meudon, France e-mail: [email protected] 2 Sydney Institute for Astronomy (SIfA), School of Physics, The University of Sydney, NSW 2006, Australia Received 14 May 2014 / Accepted 14 March 2015 ABSTRACT Context. Polarimetry is one of the keys to enhanced direct imaging of exoplanets. Not only does it deliver a differential observable pro- viding extra contrast, but when coupled with spectroscopy, it also reveals valuable information on the exoplanetary atmospheric com- position. Nevertheless, angular separation and contrast ratio to the host-star make for extremely challenging observation. Producing detailed predictions for exactly how the expected signals should appear is of critical importance for the designs and observational strategies of tomorrow’s telescopes. Aims. We aim at accurately determining the magnitudes and evolution of the main observational signatures for imaging an exoplanet: separation, contrast ratio to the host-star and polarization as a function of the orbital geometry and the reflectance parameters of the exoplanet. Methods. These parameters were used to construct a polarized-reflectance model based on the input of orbital parameters and two albedo values. The model is able to calculate a variety of observational predictions for exoplanets at any orbital time. Results. The inter-dependency of the three main observational criteria – angular separation, contrast ratio, polarization – result in a complex time-evolution of the system. -

University of California Santa Cruz

UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA SANTA CRUZ BENEATH THE SURFACE OF GIANT PLANETS: EVOLUTION, STRUCTURE, AND COMPOSITION A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY in ASTRONOMY AND ASTROPHYSICS by Neil L Kelly Miller March 2013 The Dissertation of Neil L Kelly Miller is approved: Jonathan Fortney, Chair Professor D. Lin Professor P. Garaud Professor P. Bodenheimer Tyrus Miller Vice Provost and Dean of Graduate Studies Copyright c by Neil L Kelly Miller 2013 Table of Contents List of Figures v List of Tables xii Abstract xiii Dedication xv Acknowledgments xvi 1 Introduction 1 1.1 TheSolarSystemGiantPlanets . 3 1.2 FromIndividualSystemstoSamples . 4 1.3 Physical Processes in the Evolution of Giant Planets . ........ 8 2 Coupled Thermal and Tidal Evolution of Giant Expolanets 14 2.1 Abstract.................................... 14 2.2 Introduction.................................. 15 2.3 Model:Introduction ............................. 21 2.4 Model:Implementation ........................... 23 2.5 GeneralExamples .............................. 29 2.6 Results..................................... 37 2.6.1 SpecificSystems ........................... 37 2.6.2 SummaryforSuite .......................... 47 ′ 2.6.3 High Qs cases............................. 56 2.7 Discussion&Conclusions . 59 3 Applications of Giant Planet Thermal Evolution Model 74 3.1 Introduction.................................. 74 3.2 CoRoT-2b: Young Planet With Potentially Tidally Inflated Radius . 75 3.3 CoRoT-7b: Potential Evaporative Mass Loss Scenario . ....... 78 3.3.1 EvaporativeMassLossModel. 80 iii 3.3.2 PlanetEvolution ........................... 82 3.4 Kepler11 ................................... 82 3.4.1 Formation and Compositions of Kepler 11 Planets . 82 4 Measuring the Heavy Element Composition of Giant Exoplanets with Lower Irradiation 86 4.1 Abstract.................................... 86 4.2 Introduction.................................. 87 4.3 ModelandMethod............................. -

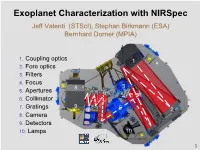

Exoplanet Characterization with Nirspec

Exoplanet Characterization with NIRSpec Jeff Valenti (STScI), Stephan Birkmann (ESA) Bernhard Dorner (MPIA) 1. Coupling optics 1 2. Fore optics 3. Filters 4. Focus 8 3 5. Apertures 6 4 6. Collimator 9 7. Gratings 7 5 2 8. Camera 9. Detectors 10. Lamps 10 1 NIRSpec Apertures Aperture Spectral Spatial S1600 1.6” 1.6” S400 0.4” 3.65” S200 0.2” 3.2” IFU 36 x 0.1” 3.6” MSA 2 x 95” 2 x 87” The S1600 aperture was designed for exoplanet observations 2 Noise Due to Jitter 1σ Jitter Jitter of 7 mas causes relative noise of 4 x 10-5 From PhD thesis Bernhard Dorner 3 NIRSpec Optical Configurations Grating Filter Wavelengths Resolution PRISM CLEAR 0.6 – 5.0 30 – 300 “100” F070LP 0.7 – 1.2 500 – 850 G140M F100LP 1.0 – 1.8 “1000” G235M F170LP 1.7 – 3.0 700 – 1300 G395M F290LP 2.9 – 5.0 F070LP 0.7 – 1.2 1300 – 2300 G140H F100LP 1.0 – 1.8 “2700” G235H F170LP 1.7 – 3.0 1900 – 3600 G395H F290LP 2.9 – 5.0 4 http://www.cosmos.esa.int/web/jwst/nirspec-performances 5 6 http://www.cosmos.esa.int/web/jwst/nirspec-performances Example of High-Resolution Model Spectra G395H Figure 4b of Burrows, Budaj, & Hubeny (2008) 7 Thermal Emission from a Hot Jupiter Adapted from Figure 4b of Burrows, Budaj, & Hubeny (2008) 8 Integrations and Exposures " An “exposure” is a sequence of integrations. " An “integration” is a sequence of groups, sampled up-the-ramp " One or more resets between integrations, but no other overheads " Currently using pixel-by-pixel resets, but row-by-row possible 9 Subarrays NX NY Frame time (s) Notes 2048 512 10.74 Full frame, 4 amps 2048 256 5.49 -

Transit Timing Analysis of the Hot Jupiters WASP-43B and WASP-46B and the Super Earth Gj1214b

Transit timing analysis of the hot Jupiters WASP-43b and WASP-46b and the super Earth GJ1214b Mathias Polfliet Promotors: Michaël Gillon, Maarten Baes 1 Abstract Transit timing analysis is proving to be a promising method to detect new planetary partners in systems which already have known transiting planets, particularly in the orbital resonances of the system. In these resonances we might be able to detect Earth-mass objects well below the current detection and even theoretical (due to stellar variability) thresholds of the radial velocity method. We present four new transits for WASP-46b, four new transits for WASP-43b and eight new transits for GJ1214b observed with the robotic telescope TRAPPIST located at ESO La Silla Observatory, Chile. Modelling the data was done using several Markov Chain Monte Carlo (MCMC) simulations of the new transits with old data and a collection of transit timings for GJ1214b from published papers. For the hot Jupiters this lead to a general increase in accuracy for the physical parameters of the system (for the mass and period we found: 2.034±0.052 MJup and 0.81347460±0.00000048 days and 2.03±0.13 MJup and 1.4303723±0.0000011 days for WASP-43b and WASP-46b respectively). For GJ1214b this was not the case given the limited photometric precision of TRAPPIST. The additional timings however allowed us to constrain the period to 1.580404695±0.000000084 days and the RMS of the TTVs to 16 seconds. We investigated given systems for Transit Timing Variations (TTVs) and variations in the other transit parameters and found no significant (3sv) deviations. -

THE MASS of KOI-94D and a RELATION for PLANET RADIUS, MASS, and INCIDENT FLUX∗

The Astrophysical Journal, 768:14 (19pp), 2013 May 1 doi:10.1088/0004-637X/768/1/14 C 2013. The American Astronomical Society. All rights reserved. Printed in the U.S.A. THE MASS OF KOI-94d AND A RELATION FOR PLANET RADIUS, MASS, AND INCIDENT FLUX∗ Lauren M. Weiss1,12, Geoffrey W. Marcy1, Jason F. Rowe2, Andrew W. Howard3, Howard Isaacson1, Jonathan J. Fortney4, Neil Miller4, Brice-Olivier Demory5, Debra A. Fischer6, Elisabeth R. Adams7, Andrea K. Dupree7, Steve B. Howell2, Rea Kolbl1, John Asher Johnson8, Elliott P. Horch9, Mark E. Everett10, Daniel C. Fabrycky11, and Sara Seager5 1 B-20 Hearst Field Annex, Astronomy Department, University of California, Berkeley, Berkeley, CA 94720, USA; [email protected] 2 NASA Ames Research Center, Moffett Field, CA 94035, USA 3 Institute for Astronomy, University of Hawaii, 2680 Woodlawn Drive, Honolulu, HI 96822, USA 4 Department of Astronomy & Astrophysics, University of California, Santa Cruz, 1156 High Street, 275 Interdisciplinary Sciences Building (ISB), Santa Cruz, CA 95064, USA 5 Massachusetts Institute of Technology, 77 Massachusetts Avenue, Cambridge, MA 02139, USA 6 Department of Astronomy, Yale University, P.O. Box 208101, New Haven, CT 06510-8101, USA 7 Harvard-Smithsonian Center for Astrophysics, 60 Garden Street, Cambridge, MA 02138, USA 8 California Institute of Technology, 1216 E. California Blvd., Pasadena, CA 91106, USA 9 Southern Connecticut State University, Department of Physics, 501 Crescent St., New Haven, CT 06515, USA 10 National Optical Astronomy Observatory, 950 N. Cherry Ave, Tucson, AZ 85719, USA 11 The Department of Astronomy and Astrophysics, University of Chicago, 5640 S. -

Direct Measure of Radiative and Dynamical Properties of an Exoplanet Atmosphere

DIRECT MEASURE OF RADIATIVE AND DYNAMICAL PROPERTIES OF AN EXOPLANET ATMOSPHERE The MIT Faculty has made this article openly available. Please share how this access benefits you. Your story matters. Citation Wit, Julien de, et al. “DIRECT MEASURE OF RADIATIVE AND DYNAMICAL PROPERTIES OF AN EXOPLANET ATMOSPHERE.” The Astrophysical Journal, vol. 820, no. 2, Mar. 2016, p. L33. © 2016 The American Astronomical Society. As Published http://dx.doi.org/10.3847/2041-8205/820/2/L33 Publisher American Astronomical Society Version Final published version Citable link http://hdl.handle.net/1721.1/114269 Terms of Use Article is made available in accordance with the publisher's policy and may be subject to US copyright law. Please refer to the publisher's site for terms of use. The Astrophysical Journal Letters, 820:L33 (6pp), 2016 April 1 doi:10.3847/2041-8205/820/2/L33 © 2016. The American Astronomical Society. All rights reserved. DIRECT MEASURE OF RADIATIVE AND DYNAMICAL PROPERTIES OF AN EXOPLANET ATMOSPHERE Julien de Wit1, Nikole K. Lewis2, Jonathan Langton3, Gregory Laughlin4, Drake Deming5, Konstantin Batygin6, and Jonathan J. Fortney4 1 Department of Earth, Atmospheric and Planetary Sciences, MIT, 77 Massachusetts Avenue, Cambridge, MA 02139, USA 2 Space Telescope Science Institute, 3700 San Martin Drive, Baltimore, MD 21218, USA 3 Department of Physics, Principia College, Elsah, IL 62028, USA 4 Department of Astronomy and Astrophysics, University of California, Santa Cruz, CA 95064, USA 5 Department of Astronomy, University of Maryland at College Park, College Park, MD 20742, USA 6 Division of Geological and Planetary Sciences, California Institute of Technology, Pasadena, CA 91125, USA Received 2016 January 28; accepted 2016 February 18; published 2016 March 28 ABSTRACT Two decades after the discovery of 51Pegb, the formation processes and atmospheres of short-period gas giants remain poorly understood. -

ON the INCLINATION DEPENDENCE of EXOPLANET PHASE SIGNATURES Stephen R

The Astrophysical Journal, 729:74 (6pp), 2011 March 1 doi:10.1088/0004-637X/729/1/74 C 2011. The American Astronomical Society. All rights reserved. Printed in the U.S.A. ON THE INCLINATION DEPENDENCE OF EXOPLANET PHASE SIGNATURES Stephen R. Kane and Dawn M. Gelino NASA Exoplanet Science Institute, Caltech, MS 100-22, 770 South Wilson Avenue, Pasadena, CA 91125, USA; [email protected] Received 2011 December 2; accepted 2011 January 5; published 2011 February 10 ABSTRACT Improved photometric sensitivity from space-based telescopes has enabled the detection of phase variations for a small sample of hot Jupiters. However, exoplanets in highly eccentric orbits present unique opportunities to study the effects of drastically changing incident flux on the upper atmospheres of giant planets. Here we expand upon previous studies of phase functions for these planets at optical wavelengths by investigating the effects of orbital inclination on the flux ratio as it interacts with the other effects induced by orbital eccentricity. We determine optimal orbital inclinations for maximum flux ratios and combine these calculations with those of projected separation for application to coronagraphic observations. These are applied to several of the known exoplanets which may serve as potential targets in current and future coronagraph experiments. Key words: planetary systems – techniques: photometric 1. INTRODUCTION and inclination for a given eccentricity. We further calculate projected separations at apastron as a function of inclination The changing phases of an exoplanet as it orbits the host star and determine their correspondence with maximum flux ratio have long been considered as a means for their detection and locations. -

IAU Division C Working Group on Star Names 2019 Annual Report

IAU Division C Working Group on Star Names 2019 Annual Report Eric Mamajek (chair, USA) WG Members: Juan Antonio Belmote Avilés (Spain), Sze-leung Cheung (Thailand), Beatriz García (Argentina), Steven Gullberg (USA), Duane Hamacher (Australia), Susanne M. Hoffmann (Germany), Alejandro López (Argentina), Javier Mejuto (Honduras), Thierry Montmerle (France), Jay Pasachoff (USA), Ian Ridpath (UK), Clive Ruggles (UK), B.S. Shylaja (India), Robert van Gent (Netherlands), Hitoshi Yamaoka (Japan) WG Associates: Danielle Adams (USA), Yunli Shi (China), Doris Vickers (Austria) WGSN Website: https://www.iau.org/science/scientific_bodies/working_groups/280/ WGSN Email: [email protected] The Working Group on Star Names (WGSN) consists of an international group of astronomers with expertise in stellar astronomy, astronomical history, and cultural astronomy who research and catalog proper names for stars for use by the international astronomical community, and also to aid the recognition and preservation of intangible astronomical heritage. The Terms of Reference and membership for WG Star Names (WGSN) are provided at the IAU website: https://www.iau.org/science/scientific_bodies/working_groups/280/. WGSN was re-proposed to Division C and was approved in April 2019 as a functional WG whose scope extends beyond the normal 3-year cycle of IAU working groups. The WGSN was specifically called out on p. 22 of IAU Strategic Plan 2020-2030: “The IAU serves as the internationally recognised authority for assigning designations to celestial bodies and their surface features. To do so, the IAU has a number of Working Groups on various topics, most notably on the nomenclature of small bodies in the Solar System and planetary systems under Division F and on Star Names under Division C.” WGSN continues its long term activity of researching cultural astronomy literature for star names, and researching etymologies with the goal of adding this information to the WGSN’s online materials. -

Exoplanet Detection Techniques

Exoplanet Detection Techniques Debra A. Fischer1, Andrew W. Howard2, Greg P. Laughlin3, Bruce Macintosh4, Suvrath Mahadevan5;6, Johannes Sahlmann7, Jennifer C. Yee8 We are still in the early days of exoplanet discovery. Astronomers are beginning to model the atmospheres and interiors of exoplanets and have developed a deeper understanding of processes of planet formation and evolution. However, we have yet to map out the full complexity of multi-planet architectures or to detect Earth analogues around nearby stars. Reaching these ambitious goals will require further improvements in instru- mentation and new analysis tools. In this chapter, we provide an overview of five observational techniques that are currently employed in the detection of exoplanets: optical and IR Doppler measurements, transit pho- tometry, direct imaging, microlensing, and astrometry. We provide a basic description of how each of these techniques works and discuss forefront developments that will result in new discoveries. We also highlight the observational limitations and synergies of each method and their connections to future space missions. Subject headings: 1. Introduction tary; in practice, they are not generally applied to the same sample of stars, so our detection of exoplanet architectures Humans have long wondered whether other solar sys- has been piecemeal. The explored parameter space of ex- tems exist around the billions of stars in our galaxy. In the oplanet systems is a patchwork quilt that still has several past two decades, we have progressed from a sample of one missing squares. to a collection of hundreds of exoplanetary systems. Instead of an orderly solar nebula model, we now realize that chaos 2. -

Exoplanetary Geophysics--An Emerging Discipline

Invited Review for Treatise on Geophysics, 2nd Edition Exoplanetary Geophysics { An Emerging Discipline Gregory Laughlin UCO/Lick Observatory, University of California, Santa Cruz, Santa Cruz, CA 95064, USA Jack J. Lissauer NASA Ames Research Center, Planetary Systems Branch, Moffett Field, CA 94035, USA 1. Abstract Thousands of extrasolar planets have been discovered, and it is clear that the galactic planetary census draws on a diversity greatly exceeding that exhibited by the solar system's planets. We review significant landmarks in the chronology of extrasolar planet detection, and we give an overview of the varied observational techniques that are brought to bear. We then discuss the properties of the planetary distribution that is currently known, using the mass-period diagram as a guide to delineating hot Jupiters, eccentric giant planets, and a third, highly populous, category that we term \ungiants", planets having masses M < 30 M⊕ and orbital periods P < 100 d. We then move to a discussion of the bulk compositions of the extrasolar planets, with particular attention given to the distribution of planetary densities. We discuss the long-standing problem of radius anomalies among giant planets, as well as issues posed by the unexpectedly large range in sizes observed for planets with mass somewhat greater than Earth's. We discuss the use of transit observations to probe the atmospheres of extrasolar planets; various measurements taken during primary transit, secondary eclipse, and through the full orbital period, can give clues to the atmospheric compositions, structures and meteorologies. The extrasolar planet catalog, along with the details of our solar system and observations of star-forming regions and protoplanetary disks, arXiv:1501.05685v1 [astro-ph.EP] 22 Jan 2015 provide a backdrop for a discussion of planet formation in which we review the elements of the favored pictures for how the terrestrial and giant planets were assembled. -

Characterization of the HD 17156 Planetary System�,

A&A 503, 601–612 (2009) Astronomy DOI: 10.1051/0004-6361/200811466 & c ESO 2009 Astrophysics Characterization of the HD 17156 planetary system, M. Barbieri1, R. Alonso1,S.Desidera2, A. Sozzetti3, A. F. Martinez Fiorenzano4,J.M.Almenara5, M. Cecconi4, R. U. Claudi2, D. Charbonneau7 ,M.Endl8, V. Granata2,9, R. Gratton2,G.Laughlin10, B. Loeillet1,6, and Exoplanet Amateur Consortium 1 Laboratoire d’Astrophysique de Marseille, 38 rue Joliot-Curie, 13388 Marseille Cedex 13, France e-mail: [email protected] 2 INAF Osservatorio Astronomico di Padova, Vicolo dell’ Osservatorio 5, 35122 Padova, Italy 3 INAF Osservatorio Astronomico di Torino, 10025 Pino Torinese, Italy 4 Fundación Galileo Galilei – INAF, Rambla José Ana Fernández Pérez 7, 38712 Breña Baja (TF), Spain 5 Instituto de Astrofísica de Canarias, C/Vía Láctea s/n, 38200 La Laguna, Spain 6 IAP, 98bis Bd Arago, 75014 Paris, France 7 Harvard-Smithsonian Center for Astrophysics, 60 Garden Street, Cambridge, MA 02138, USA 8 McDonald Observatory, The University of Texas at Austin, Austin, TX 78712, USA 9 CISAS, Università di Padova, Italy 10 University of California Observatories, University of California at Santa Cruz Santa Cruz, CA 95064, USA Received 2 December 2008 / Accepted 12 March 2009 ABSTRACT Aims. We present data to improve the known parameters of the HD 17156 system (peculiar due to the eccentricity and long orbital period of its transiting planet) and constrain the presence of stellar companions. Methods. Photometric data were acquired for 4 transits, and high precision radial velocity measurements were simultaneously acquired with the SARG spectrograph at TNG for one transit. -

Detailed Chemical Compositions of the Wide Binary HD 80606/80607: Revised Stellar Properties and Constraints on Planet Formation?,?? F

A&A 614, A138 (2018) Astronomy https://doi.org/10.1051/0004-6361/201832701 & c ESO 2018 Astrophysics Detailed chemical compositions of the wide binary HD 80606/80607: revised stellar properties and constraints on planet formation?;?? F. Liu1, D. Yong2, M. Asplund2, S. Feltzing1, A. J. Mustill1, J. Meléndez3, I. Ramírez4, and J. Lin2 1 Lund Observatory, Department of Astronomy and Theoretical physics, Lund University, Box 43, 22100 Lund, Sweden e-mail: [email protected] 2 Research School of Astronomy and Astrophysics, Australian National University, Canberra, ACT 2611, Australia 3 Departamento de Astronomia do IAG/USP, Universidade de São Paulo, Rua do Matão 1226, São Paulo 05508-900, SP, Brazil 4 Tacoma Community College, 6501 S. 19th Street, Tacoma, WA 98466, USA Received 25 January 2018 / Accepted 25 February 2018 ABSTRACT Differences in the elemental abundances of planet-hosting stars in binary systems can give important clues and constraints about planet formation and evolution. In this study we performed a high-precision, differential elemental abundance analysis of a wide binary system, HD 80606/80607, based on high-resolution spectra with high signal-to-noise ratio obtained with Keck/HIRES. HD 80606 is known to host a giant planet with the mass of four Jupiters, but no planet has been detected around HD 80607 so far. We determined stellar parameters as well as abundances for 23 elements for these two stars with extremely high precision. Our main results are that (i) we confirmed that the two components share very similar chemical compositions, but HD 80606 is marginally more metal-rich than HD 80607, with an average difference of +0.013 ± 0.002 dex (σ = 0.009 dex); and (ii) there is no obvious trend between abundance differences and condensation temperature.