Radial Velocity Transit Animation by European Southern Observatory Animation by NASA Goddard Media Studios

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Where Are the Distant Worlds? Star Maps

W here Are the Distant Worlds? Star Maps Abo ut the Activity Whe re are the distant worlds in the night sky? Use a star map to find constellations and to identify stars with extrasolar planets. (Northern Hemisphere only, naked eye) Topics Covered • How to find Constellations • Where we have found planets around other stars Participants Adults, teens, families with children 8 years and up If a school/youth group, 10 years and older 1 to 4 participants per map Materials Needed Location and Timing • Current month's Star Map for the Use this activity at a star party on a public (included) dark, clear night. Timing depends only • At least one set Planetary on how long you want to observe. Postcards with Key (included) • A small (red) flashlight • (Optional) Print list of Visible Stars with Planets (included) Included in This Packet Page Detailed Activity Description 2 Helpful Hints 4 Background Information 5 Planetary Postcards 7 Key Planetary Postcards 9 Star Maps 20 Visible Stars With Planets 33 © 2008 Astronomical Society of the Pacific www.astrosociety.org Copies for educational purposes are permitted. Additional astronomy activities can be found here: http://nightsky.jpl.nasa.gov Detailed Activity Description Leader’s Role Participants’ Roles (Anticipated) Introduction: To Ask: Who has heard that scientists have found planets around stars other than our own Sun? How many of these stars might you think have been found? Anyone ever see a star that has planets around it? (our own Sun, some may know of other stars) We can’t see the planets around other stars, but we can see the star. -

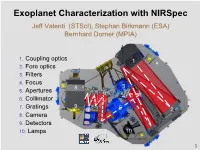

Exoplanet Characterization with Nirspec

Exoplanet Characterization with NIRSpec Jeff Valenti (STScI), Stephan Birkmann (ESA) Bernhard Dorner (MPIA) 1. Coupling optics 1 2. Fore optics 3. Filters 4. Focus 8 3 5. Apertures 6 4 6. Collimator 9 7. Gratings 7 5 2 8. Camera 9. Detectors 10. Lamps 10 1 NIRSpec Apertures Aperture Spectral Spatial S1600 1.6” 1.6” S400 0.4” 3.65” S200 0.2” 3.2” IFU 36 x 0.1” 3.6” MSA 2 x 95” 2 x 87” The S1600 aperture was designed for exoplanet observations 2 Noise Due to Jitter 1σ Jitter Jitter of 7 mas causes relative noise of 4 x 10-5 From PhD thesis Bernhard Dorner 3 NIRSpec Optical Configurations Grating Filter Wavelengths Resolution PRISM CLEAR 0.6 – 5.0 30 – 300 “100” F070LP 0.7 – 1.2 500 – 850 G140M F100LP 1.0 – 1.8 “1000” G235M F170LP 1.7 – 3.0 700 – 1300 G395M F290LP 2.9 – 5.0 F070LP 0.7 – 1.2 1300 – 2300 G140H F100LP 1.0 – 1.8 “2700” G235H F170LP 1.7 – 3.0 1900 – 3600 G395H F290LP 2.9 – 5.0 4 http://www.cosmos.esa.int/web/jwst/nirspec-performances 5 6 http://www.cosmos.esa.int/web/jwst/nirspec-performances Example of High-Resolution Model Spectra G395H Figure 4b of Burrows, Budaj, & Hubeny (2008) 7 Thermal Emission from a Hot Jupiter Adapted from Figure 4b of Burrows, Budaj, & Hubeny (2008) 8 Integrations and Exposures " An “exposure” is a sequence of integrations. " An “integration” is a sequence of groups, sampled up-the-ramp " One or more resets between integrations, but no other overheads " Currently using pixel-by-pixel resets, but row-by-row possible 9 Subarrays NX NY Frame time (s) Notes 2048 512 10.74 Full frame, 4 amps 2048 256 5.49 -

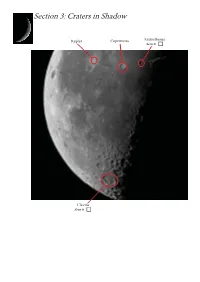

Craters in Shadow

Section 3: Craters in Shadow Kepler Copernicus Eratosthenes Seen it Clavius Seen it Section 3: Craters in Shadow Visibility: A pair of binoculars is the minimum requirement to see these features. When: Look for them when the terminator’s close by, typically a day before last quarter. Not all craters are best seen when the Sun is high in the lunar sky - in fact most aren’t! If craters aren’t par- ticularly bright or dark, they tend to disappear into the background when the Moon’s phase is close to full. These craters are best seen when the ‘terminator’ is nearby, or when the Sun is low in the lunar sky as seen from the crater. This causes oblique lighting to fall on the crater and create exaggerated shadows. Ultimately, this makes the crater look more dramatic and easier to see. We’ll use this effect for the next section on lunar mountains, but before we do, there are a couple of craters that we’d like to bring to your attention. Actually, the Moon is covered with a whole host of wonderful craters that look amazing when the lighting is oblique. During the summer and into the early autumn, it’s the later phases of the Moon are best positioned in the sky - the phases following full Moon. Unfortunately, this means viewing in the early hours but don’t worry as we’ve kept things simple. We just want to give you a taste of what a shadowed crater looks like for this marathon, so the going here is really pretty easy! First, locate the two craters Kepler and Copernicus which were marathon targets pointed out in Section 2. -

2-6-NASA Exoplanet Archive

The NASA Exoplanet Archive Rachel Akeson NASA Exoplanet Science Ins5tute (NExScI) September 29, 2016 NASA Big Data Task Force Overview: Dat a NASA Exoplanet Archive supports both the exoplanet science community and NASA exoplanet missions (Kepler, K2, TESS, WFIRST) • Data • Confirmed exoplanets from the literature • Over 80,000 planetary and stellar parameter values for 3388 exoplanets • Updated weekly • Kepler stellar proper5es, planet candidate, data valida5on and occurrence rate products • MAST is archive for pixel and light curve data • Addi5onal space (CoRoT) and ground-based transit surveys (~20 million light curves) • Transit spectroscopy data • Auto-updated exoplanet plots and movies Big Data Task Force: Exoplanet Archive Overview: Tool s Example: Kepler 14 Time Series Viewer • Interac5ve tables and ploZng for data • Includes light curve normaliza5on • Periodogram calcula5ons • Searches for periodic signals in archive or user-supplied light curves • Transit predic5ons • Uses value from archive to predict future planet transits for observa5on and mission planning • URL-based queries Aliases • Calcula5on of observable proper5es Planet orbital period • Web-based service to collect follow-up observa5ons of planet candidates for Kepler, K2 and TESS (ExoFOP) Stellar ac5vity • Includes user-supplied data, file and notes Big Data Task Force: Exoplanet Archive Data Challenges and Technical Approach (1) • Challenges with Exoplanet Archive are not currently about data volume but about providing CPU resources and data complexity • CPU challenge -

College of San Mateo Observatory Stellar Spectra Catalog ______

College of San Mateo Observatory Stellar Spectra Catalog SGS Spectrograph Spectra taken from CSM observatory using SBIG Self Guiding Spectrograph (SGS) ___________________________________________________ A work in progress compiled by faculty, staff, and students. Stellar Spectroscopy Stars are divided into different spectral types, which result from varying atomic-level activity on the star, due to its surface temperature. In spectroscopy, we measure this activity via a spectrograph/CCD combination, attached to a moderately sized telescope. The resultant data are converted to graphical format for further analysis. The main spectral types are characterized by the letters O,B,A,F,G,K, & M. Stars of O type are the hottest, as well as the rarest. Stars of M type are the coolest, and by far, the most abundant. Each spectral type is also divided into ten subtypes, ranging from 0 to 9, further delineating temperature differences. Type Temperature Color O 30,000 - 60,000 K Blue B 10,000 - 30,000 K Blue-white A 7,500 - 10,000 K White F 6,000 - 7,500 K Yellow-white G 5,000 - 6,000 K Yellow K 3,500 - 5,000 K Yellow-orange M >3,500 K Red Class Spectral Lines O -Weak neutral and ionized Helium, weak Hydrogen, a relatively smooth continuum with very few absorption lines B -Weak neutral Helium, stronger Hydrogen, an otherwise relatively smooth continuum A -No Helium, very strong Hydrogen, weak CaII, the continuum is less smooth because of weak ionized metal lines F -Strong Hydrogen, strong CaII, weak NaI, G-band, the continuum is rougher because of many ionized metal lines G -Weaker Hydrogen, strong CaII, stronger NaI, many ionized and neutral metals, G-band is present K -Very weak Hydrogen, strong CaII, strong NaI and many metals G- band is present M -Strong TiO molecular bands, strongest NaI, weak CaII very weak Hydrogen absorption. -

The Detectability and Constraints of Biosignature Gasses in the Near & Mid-Infrared from Transit Transmission Spectroscopy B

The Detectability and Constraints of Biosignature Gasses in the Near & Mid-Infrared from Transit Transmission Spectroscopy by Luke Tremblay A Thesis Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Master of Science Approved November 2019 by the Graduate Supervisory Committee: Michael Line, Chair Evgenya Schkolnik Sara Walker ARIZONA STATE UNIVERSITY December 2019 ABSTRACT The James Webb Space Telescope (JWST ) is expected to revolutionize the cur- rent understanding of Jovian worlds over the coming decade. However, as the field pushes towards characterizing cooler, smaller, \terrestrial-like" planets, dedicated next-generation facilities will be required to tease out the small spectral signatures indicative of biological activity. Here, the feasibility of determining atmospheric prop- erties, from near to mid-infrared transmission spectra, of transiting temperate ter- restrial M-dwarf companions, has been evaluated. Specifically, atmospheric retrievals were utilized to explore the trade space between spectral resolution, wavelength cover- age, and signal-to-noise on the ability to both detect molecular species and constrain their abundances. Increasing spectral resolution beyond R=100 for near-infrared wavelengths, shorter than 5µm, proves to reduce the degeneracy between spectral features of different molecules and thus greatly benefits the abundance constraints. However, this benefit is greatly diminished beyond 5µm as any overlap between broad features in the mid-infrared does not deconvolve with higher resolutions. Additionally, the inclusion of features beyond 11µm did not meaningfully improve the detection sig- nificance nor abundance constraints results. The findings of this study indicate that an instrument with continuous wavelength coverage from approximately 2-11µm and with a resolution of R'50-300, would be capable of detecting H2O, CO2, CH4,O3, and N2O in the atmosphere of an Earth-analog transiting an M-dwarf (magK =8.0) within 50 transits, and obtain better than an order-of-magnitude constraint on each of their abundances. -

THE MASS of KOI-94D and a RELATION for PLANET RADIUS, MASS, and INCIDENT FLUX∗

The Astrophysical Journal, 768:14 (19pp), 2013 May 1 doi:10.1088/0004-637X/768/1/14 C 2013. The American Astronomical Society. All rights reserved. Printed in the U.S.A. THE MASS OF KOI-94d AND A RELATION FOR PLANET RADIUS, MASS, AND INCIDENT FLUX∗ Lauren M. Weiss1,12, Geoffrey W. Marcy1, Jason F. Rowe2, Andrew W. Howard3, Howard Isaacson1, Jonathan J. Fortney4, Neil Miller4, Brice-Olivier Demory5, Debra A. Fischer6, Elisabeth R. Adams7, Andrea K. Dupree7, Steve B. Howell2, Rea Kolbl1, John Asher Johnson8, Elliott P. Horch9, Mark E. Everett10, Daniel C. Fabrycky11, and Sara Seager5 1 B-20 Hearst Field Annex, Astronomy Department, University of California, Berkeley, Berkeley, CA 94720, USA; [email protected] 2 NASA Ames Research Center, Moffett Field, CA 94035, USA 3 Institute for Astronomy, University of Hawaii, 2680 Woodlawn Drive, Honolulu, HI 96822, USA 4 Department of Astronomy & Astrophysics, University of California, Santa Cruz, 1156 High Street, 275 Interdisciplinary Sciences Building (ISB), Santa Cruz, CA 95064, USA 5 Massachusetts Institute of Technology, 77 Massachusetts Avenue, Cambridge, MA 02139, USA 6 Department of Astronomy, Yale University, P.O. Box 208101, New Haven, CT 06510-8101, USA 7 Harvard-Smithsonian Center for Astrophysics, 60 Garden Street, Cambridge, MA 02138, USA 8 California Institute of Technology, 1216 E. California Blvd., Pasadena, CA 91106, USA 9 Southern Connecticut State University, Department of Physics, 501 Crescent St., New Haven, CT 06515, USA 10 National Optical Astronomy Observatory, 950 N. Cherry Ave, Tucson, AZ 85719, USA 11 The Department of Astronomy and Astrophysics, University of Chicago, 5640 S. -

Naming the Extrasolar Planets

Naming the extrasolar planets W. Lyra Max Planck Institute for Astronomy, K¨onigstuhl 17, 69177, Heidelberg, Germany [email protected] Abstract and OGLE-TR-182 b, which does not help educators convey the message that these planets are quite similar to Jupiter. Extrasolar planets are not named and are referred to only In stark contrast, the sentence“planet Apollo is a gas giant by their assigned scientific designation. The reason given like Jupiter” is heavily - yet invisibly - coated with Coper- by the IAU to not name the planets is that it is consid- nicanism. ered impractical as planets are expected to be common. I One reason given by the IAU for not considering naming advance some reasons as to why this logic is flawed, and sug- the extrasolar planets is that it is a task deemed impractical. gest names for the 403 extrasolar planet candidates known One source is quoted as having said “if planets are found to as of Oct 2009. The names follow a scheme of association occur very frequently in the Universe, a system of individual with the constellation that the host star pertains to, and names for planets might well rapidly be found equally im- therefore are mostly drawn from Roman-Greek mythology. practicable as it is for stars, as planet discoveries progress.” Other mythologies may also be used given that a suitable 1. This leads to a second argument. It is indeed impractical association is established. to name all stars. But some stars are named nonetheless. In fact, all other classes of astronomical bodies are named. -

Platform-Independent Mobile Robot Communication

Philipp A. Baer Platform-Independent Development of Robot Communication Software kassel university press This work has been accepted by the faculty of Electrical Engineering and Computer Science of the University of Kassel as a thesis for acquiring the academic degree of Doktor der Ingenieurwissenschaften (Dr.-Ing.). Advisers: Prof. Dr. Kurt Geihs Prof. Dr. Gerhard K. Kraetzschmar Additional Doctoral Committee Members: Prof. Dr. Albert Zündorf Prof. Dr. Klaus David Defense day: 04th December 2008 Bibliographic information published by Deutsche Nationalbibliothek The Deutsche Nationalbibliothek lists this publication in the Deutsche Nationalbibliografie; detailed bibliographic data is available in the Internet at http://dnb.d-nb.de. Zugl.: Kassel, Univ., Diss. 2008 ISBN print: 978-3-89958-644-2 ISBN online: 978-3-89958-645-9 URN: urn:nbn:de:0002-6453 © 2008, kassel university press GmbH, Kassel www.upress.uni-kassel.de Printed by: Unidruckerei, University of Kassel Printed in Germany Für Mutti und Mama. Mutti, du bleibst unvergessen. * 29. September 1923 = 14. Oktober 2008 Contents List of Figuresv List of Tables vii Abstract ix I Introduction1 1 Introduction3 1.1 Motivation.........................................4 1.1.1 Software Structure................................5 1.1.2 Development Methodology...........................5 1.1.3 Communication.................................6 1.1.4 Configuration and Monitoring.........................6 1.2 Problem Analysis.....................................7 1.2.1 Development Methodology...........................7 1.2.2 Communication Infrastructure........................8 1.2.3 Resource Discovery...............................8 1.3 Solution Approach....................................9 1.4 Major Results........................................ 11 1.5 Overview.......................................... 12 2 Foundations 13 2.1 Autonomous Mobile Robots............................... 13 2.1.1 Hardware Architecture............................. 14 2.1.2 Robot Software................................. -

Biosignatures Search in Habitable Planets

galaxies Review Biosignatures Search in Habitable Planets Riccardo Claudi 1,* and Eleonora Alei 1,2 1 INAF-Astronomical Observatory of Padova, Vicolo Osservatorio, 5, 35122 Padova, Italy 2 Physics and Astronomy Department, Padova University, 35131 Padova, Italy * Correspondence: [email protected] Received: 2 August 2019; Accepted: 25 September 2019; Published: 29 September 2019 Abstract: The search for life has had a new enthusiastic restart in the last two decades thanks to the large number of new worlds discovered. The about 4100 exoplanets found so far, show a large diversity of planets, from hot giants to rocky planets orbiting small and cold stars. Most of them are very different from those of the Solar System and one of the striking case is that of the super-Earths, rocky planets with masses ranging between 1 and 10 M⊕ with dimensions up to twice those of Earth. In the right environment, these planets could be the cradle of alien life that could modify the chemical composition of their atmospheres. So, the search for life signatures requires as the first step the knowledge of planet atmospheres, the main objective of future exoplanetary space explorations. Indeed, the quest for the determination of the chemical composition of those planetary atmospheres rises also more general interest than that given by the mere directory of the atmospheric compounds. It opens out to the more general speculation on what such detection might tell us about the presence of life on those planets. As, for now, we have only one example of life in the universe, we are bound to study terrestrial organisms to assess possibilities of life on other planets and guide our search for possible extinct or extant life on other planetary bodies. -

Exep Science Plan Appendix (SPA) (This Document)

ExEP Science Plan, Rev A JPL D: 1735632 Release Date: February 15, 2019 Page 1 of 61 Created By: David A. Breda Date Program TDEM System Engineer Exoplanet Exploration Program NASA/Jet Propulsion Laboratory California Institute of Technology Dr. Nick Siegler Date Program Chief Technologist Exoplanet Exploration Program NASA/Jet Propulsion Laboratory California Institute of Technology Concurred By: Dr. Gary Blackwood Date Program Manager Exoplanet Exploration Program NASA/Jet Propulsion Laboratory California Institute of Technology EXOPDr.LANET Douglas Hudgins E XPLORATION PROGRAMDate Program Scientist Exoplanet Exploration Program ScienceScience Plan Mission DirectorateAppendix NASA Headquarters Karl Stapelfeldt, Program Chief Scientist Eric Mamajek, Deputy Program Chief Scientist Exoplanet Exploration Program JPL CL#19-0790 JPL Document No: 1735632 ExEP Science Plan, Rev A JPL D: 1735632 Release Date: February 15, 2019 Page 2 of 61 Approved by: Dr. Gary Blackwood Date Program Manager, Exoplanet Exploration Program Office NASA/Jet Propulsion Laboratory Dr. Douglas Hudgins Date Program Scientist Exoplanet Exploration Program Science Mission Directorate NASA Headquarters Created by: Dr. Karl Stapelfeldt Chief Program Scientist Exoplanet Exploration Program Office NASA/Jet Propulsion Laboratory California Institute of Technology Dr. Eric Mamajek Deputy Program Chief Scientist Exoplanet Exploration Program Office NASA/Jet Propulsion Laboratory California Institute of Technology This research was carried out at the Jet Propulsion Laboratory, California Institute of Technology, under a contract with the National Aeronautics and Space Administration. © 2018 California Institute of Technology. Government sponsorship acknowledged. Exoplanet Exploration Program JPL CL#19-0790 ExEP Science Plan, Rev A JPL D: 1735632 Release Date: February 15, 2019 Page 3 of 61 Table of Contents 1. -

Winter Observing Notes

Wynyard Planetarium & Observatory Winter Observing Notes Wynyard Planetarium & Observatory PUBLIC OBSERVING – Winter Tour of the Sky with the Naked Eye NGC 457 CASSIOPEIA eta Cas Look for Notice how the constellations 5 the ‘W’ swing around Polaris during shape the night Is Dubhe yellowish compared 2 Polaris to Merak? Dubhe 3 Merak URSA MINOR Kochab 1 Is Kochab orange Pherkad compared to Polaris? THE PLOUGH 4 Mizar Alcor Figure 1: Sketch of the northern sky in winter. North 1. On leaving the planetarium, turn around and look northwards over the roof of the building. To your right is a group of stars like the outline of a saucepan standing up on it’s handle. This is the Plough (also called the Big Dipper) and is part of the constellation Ursa Major, the Great Bear. The top two stars are called the Pointers. Check with binoculars. Not all stars are white. The colour shows that Dubhe is cooler than Merak in the same way that red-hot is cooler than white-hot. 2. Use the Pointers to guide you to the left, to the next bright star. This is Polaris, the Pole (or North) Star. Note that it is not the brightest star in the sky, a common misconception. Below and to the right are two prominent but fainter stars. These are Kochab and Pherkad, the Guardians of the Pole. Look carefully and you will notice that Kochab is slightly orange when compared to Polaris. Check with binoculars. © Rob Peeling, CaDAS, 2007 version 2.0 Wynyard Planetarium & Observatory PUBLIC OBSERVING – Winter Polaris, Kochab and Pherkad mark the constellation Ursa Minor, the Little Bear.