The Doctrine of Fascism Benito Mussolini (1932)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Youth, Gender, and Education in Fascist Italy, 1922-1939 Jennifer L

James Madison University JMU Scholarly Commons Senior Honors Projects, 2010-current Honors College Spring 2015 The model of masculinity: Youth, gender, and education in Fascist Italy, 1922-1939 Jennifer L. Nehrt James Madison University Follow this and additional works at: https://commons.lib.jmu.edu/honors201019 Part of the European History Commons, History of Gender Commons, and the Social History Commons Recommended Citation Nehrt, Jennifer L., "The model of masculinity: Youth, gender, and education in Fascist Italy, 1922-1939" (2015). Senior Honors Projects, 2010-current. 66. https://commons.lib.jmu.edu/honors201019/66 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Honors College at JMU Scholarly Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Senior Honors Projects, 2010-current by an authorized administrator of JMU Scholarly Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. The Model of Masculinity: Youth, Gender, and Education in Fascist Italy, 1922-1939 _______________________ An Honors Program Project Presented to the Faculty of the Undergraduate College of Arts and Letters James Madison University _______________________ by Jennifer Lynn Nehrt May 2015 Accepted by the faculty of the Department of History, James Madison University, in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Honors Program. FACULTY COMMITTEE: HONORS PROGRAM APPROVAL: Project Advisor: Jessica Davis, Ph.D. Philip Frana, Ph.D., Associate Professor, History Interim Director, Honors Program Reader: Emily Westkaemper, Ph.D. Assistant Professor, History Reader: Christian Davis, Ph.D. Assistant Professor, History PUBLIC PRESENTATION This work is accepted for presentation, in part or in full, at Honors Symposium on April 24, 2015. -

Mussolini's Ambiguous and Opportunistic Conception of Romanità

“A Mysterious Revival of Roman Passion”: Mussolini’s Ambiguous and Opportunistic Conception of Romanità Benjamin Barron Senior Honors Thesis in History HIST-409-02 Georgetown University Mentored by Professor Foss May 4, 2009 “A Mysterious Revival of Roman Passion”: Mussolini’s Ambiguous and Opportunistic Conception of Romanità CONTENTS Preface and Acknowledgments ii List of Illustrations iii Introduction 1 I. Mussolini and the Power of Words 7 II. The Restrained Side of Mussolini’s Romanità 28 III. The Shift to Imperialism: The Second Italo-Ethiopian War 1935 – 1936 49 IV. Romanità in Mussolini’s New Roman Empire 58 Conclusion 90 Bibliography 95 i PREFACE AND ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I first came up with the topic for this thesis when I visited Rome for the first time in March of 2008. I was studying abroad for the spring semester in Milan, and my six-month experience in Italy undoubtedly influenced the outcome of this thesis. In Milan, I grew to love everything about Italy – the language, the culture, the food, the people, and the history. During this time, I traveled throughout all of Italian peninsula and, without the support of my parents, this tremendous experience would not have been possible. For that, I thank them sincerely. This thesis would not have been possible without a few others whom I would like to thank. First and foremost, thank you, Professor Astarita, for all the time you put into our Honors Seminar class during the semester. I cannot imagine how hard it must have been to read all of our drafts so intently. Your effort has not gone unnoticed. -

Primary Sources

Primary Sources Pluralism James Madison (1751-1836). Although aspects of pluralist public philosophy can be traced back to the ancient Greek philosopher Aristotle (384-322 BCE), Madison’s contributions to the Federalist Papers, written to urge ratification of the American Constitution, are now regarded as an initial anticipation and contribution to pluralist public philosophy. Madison was one of the principal authors of the American Constitution, including the Bill of Rights, and the fourth President of the United States (1809-17). The Federalist Papers with John Jay and Alexander Hamilton (1787-1788) William James (1842-1910), a leading formulator of American pragmatism, was professor of psychology and philosophy at Harvard between 1873 and 1907. His philosophical work stressed the importance of a plurality of values as an intermediate ontological “kingdom” between monistic idealism and atomistic materialism. His Varieties of Religious Experience, written in 1902, is regarded as one of the most important works in non-fiction during the10th century. Pragmatism and Other Essays, edited by Giles Gunn (Penguin, 2000) A Pluralistic Universe (Harvard University Press, 1975) Robert Dahl (1915 - ) is often described as “the Dean” of American Political Science. He was Sterling Professor of Politics at Yale University, and continues to publish prolifically on democracy since his retirement. His analysis of community power in New Haven (Who Governs?) and his widely adopted American government text (Pluralist Democracy) led to his being regarded as the chief (orthodox) pluralist, during the famous pluralist-elitist debates of the 1960s and 1970s. According to elite theorists, Dahl’s pluralism was a naïve account of a politics that claimed that power was widely dispersed among many groups and thus democracy was approximated, at least in America. -

The Startling Rise to Power of Benito Mussolini

The Journal of Values-Based Leadership Volume 11 Article 3 Issue 2 Summer/Fall 2018 July 2018 Lessons from History: The tS artling Rise to Power of Benito Mussolini Emilio F. Iodice [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://scholar.valpo.edu/jvbl Part of the Business Commons Recommended Citation Iodice, Emilio F. (2018) "Lessons from History: The tS artling Rise to Power of Benito Mussolini," The Journal of Values-Based Leadership: Vol. 11 : Iss. 2 , Article 3. Available at: http://dx.doi.org/10.22543/0733.62.1241 Available at: https://scholar.valpo.edu/jvbl/vol11/iss2/3 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the College of Business at ValpoScholar. It has been accepted for inclusion in The ourJ nal of Values-Based Leadership by an authorized administrator of ValpoScholar. For more information, please contact a ValpoScholar staff member at [email protected]. Lessons from History: The Startling Rise to Power of Benito Mussolini EMILIO IODICE, ROME, ITALY Democracy is beautiful in theory; in practice it is a fallacy. All within the state, nothing outside the state, nothing against the state. Yes, a dictator can be loved. Provided that the masses fear him at the same time. The crowd loves strong men. The crowd is like a woman. If only we can give them faith that mountains can be moved, they will accept the illusion that mountains are moveable, and thus an illusion may become reality. Italian journalism is free because it serves one cause and one purpose…mine! Better to live a day as a lion than 100 years as a sheep. -

Giuseppe Terragni, Mario Radice and the Casa Del Fascio

history Building, furniture design and the decorative arts collaborate to embody Fascist political values and mass identity in an icon of modern architecture. Furnishing the Fascist interior: Giuseppe Terragni, Mario Radice and the Casa del Fascio David Rifkind ‘The struggles, conquests, and responsibility for victory the scales of furniture and urbanism – and by contributed a mystical beauty to the humble collaborating artists, for whom constructs and headquarters, where enthusiasm for the Duce and the installations utilising photomontage acted as heroic blood sacrificed by the enlisted were often the modernist interpretations of the traditional media greatest source of comfort and the most poetic of fresco, bas-relief and mosaic. Furnishings – “furnishing”.’1 including furniture, installations and plastic arts – played an integral role in fostering three recurrent The political values of Benito Mussolini’s Fascist themes throughout Terragni’s project: establishing regime resonated throughout the architecture and the symbolic presence of the Duce; representing the furnishings of Giuseppe Terragni’s Casa del Fascio political values of the Party through the use of (1932-36) in Como [1].2 Every physical detail and materials and formal relationships; and spatial relationship in this building is invested with constructing a uniquely Fascist identity, stressing political symbolism. The building represents an national (rather than regional) allegiances and example of interwar modernism in which emphasising the formation and exploitation of a architecture and furnishings were considered as an mass identity for the public. This essay considers how integral whole, both by the architect – whose these three themes are physically manifested in the architecture operated in a middle register between building’s most important interior spaces. -

Nazi Party from Wikipedia, the Free Encyclopedia

Create account Log in Article Talk Read View source View history Nazi Party From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia This article is about the German Nazi Party that existed from 1920–1945. For the ideology, see Nazism. For other Nazi Parties, see Nazi Navigation Party (disambiguation). Main page The National Socialist German Workers' Party (German: Contents National Socialist German Nationalsozialistische Deutsche Arbeiterpartei (help·info), abbreviated NSDAP), commonly known Featured content Workers' Party in English as the Nazi Party, was a political party in Germany between 1920 and 1945. Its Current events Nationalsozialistische Deutsche predecessor, the German Workers' Party (DAP), existed from 1919 to 1920. The term Nazi is Random article Arbeiterpartei German and stems from Nationalsozialist,[6] due to the pronunciation of Latin -tion- as -tsion- in Donate to Wikipedia German (rather than -shon- as it is in English), with German Z being pronounced as 'ts'. Interaction Help About Wikipedia Community portal Recent changes Leader Karl Harrer Contact page 1919–1920 Anton Drexler 1920–1921 Toolbox Adolf Hitler What links here 1921–1945 Related changes Martin Bormann 1945 Upload file Special pages Founded 1920 Permanent link Dissolved 1945 Page information Preceded by German Workers' Party (DAP) Data item Succeeded by None (banned) Cite this page Ideologies continued with neo-Nazism Print/export Headquarters Munich, Germany[1] Newspaper Völkischer Beobachter Create a book Youth wing Hitler Youth Download as PDF Paramilitary Sturmabteilung -

The 'Regime-Model' of Fascism: a Typology

02_Articles 30/1 19/11/99 11:10 am Page 77 Aristotle A. Kallis The ‘Regime-Model’ of Fascism: A Typology Introduction In recent years there has been a revival of interest in the nature of generic fascism. This renewed search for a paradigmatic model of fascism originated as a reaction to the trend of overstating specificity, of studying fascist phenomena in the longue durée and of using their individual differences to underscore the futility of grand theories of fascism. A large part of the blame for the dis- crediting of comparative approaches is borne by the erratic and often mystifying sample of the studies themselves. Lack of clarity about the nature and content of fascism resulted in a number of comparative studies, whose insufficiently justified sample of case studies left the concept of ‘fascism’ in disarray. The ‘totalitarian’ approach focused on the political features of fascism as regime (i.e. Italy and Germany), but then subjected it to a broader definition which dovetailed with aspects of such a disparate socio-political phenomenon as communism.1 Nolte’s Three Faces of Fascism provided an insightful account of the ideological similarities between the Italian and German regimes, only to obfuscate his paradigm by including Action Française in his analysis.2 The ideological affinities notwithstanding, the weak- nesses of his generic definition are obvious. If ‘fascism’ is a broad ideological phenomenon, then why are other case-studies ex- cluded (Austria, Britain, etc.)? If, on the other hand, ‘fascism’ is both ideology and action, movement and regime, then why is Action Française comparable to the Italian and German regimes? Even the recent account by Roger Eatwell has focused on a curious combination of two major interwar regimes (Italy, Germany) and a plethora of disparate movements (most of which achieved limited, short-lived appeal and none of which ever European History Quarterly Copyright © 2000 SAGE Publications, London, Thousand Oaks, CA and New Delhi, Vol. -

Introduction

Notes Introduction 1. Two statements, made in passing, by two celebrated historians of Nazism and Soviet communism respectively, are good evi- dence of this tendency to assume that totalitarianism equals a structural model of political rule. See Ian Kershaw’s observa- tion that ‘the totalitarian concept allows comparative analysis of a number of techniques and instruments of domination’ (Kershaw, ‘“Working Towards the Führer”: Reflections on the Nature of the Hitler Dictatorship’, in, Stalinism and Nazism: Dictatorships in Comparison, ed. Ian Kershaw and Moshe Lewin [Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1997], 88). See also Robert Service’s statement that ‘[f]ascism was in many ways a structural copy of [the Soviet order], albeit with a different set of ideological purposes’ (Comrades. Communism: A World History [London: Pan, 2008], 9). 2. Note that here I argue against something of an emerging consensus. The case for classifying Fascist Italy as totalitarian has recently been argued most forcefully by Emilio Gentile. See Gentile, The Sacralization of Politics in Fascist Italy, trans. by Keith Botsford (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1996). On the other hand, Hannah Arendt long ago established a convention of excluding the Italian case, mainly because it lacks a murderous aspect on anything approaching the same scale. See Arendt, The Origins of Totalitarianism (London: Schocken, 2004 [orig. 1951], esp. 256–9). 3. It is an intellectual red herring to construct an account of totali- tarianism around Mussolini’s article ‘The Doctrine of Fascism’ in the Enciclopedie Italiana of 1932 (in fact authored by the ‘philosopher’ of Fascism, Giovanni Gentile). This primary docu- ment source does have the distinction, though, of championing a positive conception of ‘totalitarian’, rendered equivalent with the Fascist conception of the state. -

The Business Plot in the American Press by Bradley M. Galka

The Business Plot in the American Press by Bradley M. Galka B.S., University at Albany, 2015 A THESIS submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree MASTER OF ARTS Department of History College of Arts and Sciences KANSAS STATE UNIVERSITY Manhattan, Kansas 2017 Approved by: Major Professor Donald J. Mrozek Copyright © Bradley Galka 2017. Abstract In the fall of 1934 Major General Smedley Butler, U.S.M.C. (ret.) testified before Congress that he had been approached by a representative of a cabal of wealthy Wall Street bankers, powerful industrial magnates, and shady political operatives to lead a fascist coup to overthrow the administration of President Franklin D. Roosevelt. Congress investigated Butler’s allegations of a conspiracy against the government and deemed them to be true. The American news media, however, was noticeably divided in the nature of their coverage of the congressional investigation. Previous historians have claimed that elements of the American news media were markedly sympathetic toward fascism in the United States during the 1930s. An analysis of the newspaper coverage of this investigation reveals a stark contrast between ways in which media outlets headed by individuals suspected of fascist sympathies portrayed the story as opposed to media outlets known to be editorially anti-fascist. These findings lend credence to previous historians’ claims about identifiably pro-fascist strains in the American media during the time in question. Table of Contents Acknowledgements ........................................................................................................................ -

“The Doctrine of Fascism” (1932) by Benito Mussolini

“The Doctrine of Fascism” (1932) by Benito Mussolini ike all sound political conceptions, Fascism is whereas, by the exercise of his free will, man can action and it is thought; action in which and must create his own world. doctrine is immanent, and doctrine arising Lfrom a given system of historical forces in Fascism wants man to be active and to engage in which it is inserted, and working on them from action with all his energies; it wants him to be within. It has therefore a form correlated to manfully aware of the difficulties besetting him contingencies of time and space; but it has also an and ready to face them. It conceives of life as a ideal content which makes it an expression of truth in struggle in which it behooves a man to win for himself a the higher region of the history of thought. There is really worthy place, first of all by fitting himself no way of exercising a spiritual influence in the world (physically, morally, intellectually) to become the as a human will dominating the will of others, unless implement required for winning it. As for the one has a conception both of the transient and the individual, so for the nation, and so for mankind. specific reality on which that action is to be exercised, Hence the high value of culture in all its forms and of the permanent and universal reality in which (artistic, religious, scientific) and the the transient dwells and has its being. To know men outstanding importance of education. -

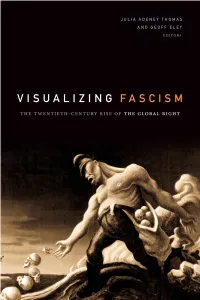

Visualizing FASCISM This Page Intentionally Left Blank Julia Adeney Thomas and Geoff Eley, Editors

Visualizing FASCISM This page intentionally left blank Julia Adeney Thomas and Geoff Eley, Editors Visualizing FASCISM The Twentieth- Century Rise of the Global Right Duke University Press | Durham and London | 2020 © 2020 Duke University Press All rights reserved Printed in the United States of America on acid- free paper ∞ Designed by Julienne Alexander / Cover designed by Matthew Tauch Typeset in Minion Pro and Haettenschweiler by Copperline Books Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Names: Eley, Geoff, [date] editor. | Thomas, Julia Adeney, [date] editor. Title: Visualizing fascism : the twentieth-century rise of the global right / Geoff Eley and Julia Adeney Thomas, editors. Description: Durham : Duke University Press, 2020. | Includes bibliographical references and index. Identifiers:lccn 2019023964 (print) lccn 2019023965 (ebook) isbn 9781478003120 (hardback : acid-free paper) isbn 9781478003762 (paperback : acid-free paper) isbn 9781478004387 (ebook) Subjects: lcsh: Fascism—History—20th century. | Fascism and culture. | Fascist aesthetics. Classification:lcc jc481 .v57 2020 (print) | lcc jc481 (ebook) | ddc 704.9/49320533—dc23 lc record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2019023964 lc ebook record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2019023965 Cover art: Thomas Hart Benton, The Sowers. © 2019 T. H. and R. P. Benton Testamentary Trusts / UMB Bank Trustee / Licensed by vaga at Artists Rights Society (ARS), NY. This publication is made possible in part by support from the Institute for Scholarship in the Liberal Arts, College of Arts and Letters, University of Notre Dame. CONTENTS ■ Introduction: A Portable Concept of Fascism 1 Julia Adeney Thomas 1 Subjects of a New Visual Order: Fascist Media in 1930s China 21 Maggie Clinton 2 Fascism Carved in Stone: Monuments to Loyal Spirits in Wartime Manchukuo 44 Paul D. -

Benito Mussolini, from "The Political and Social Doctrine of Fascism"1

Benito Mussolini, from "The Political and Social Doctrine of Fascism"1 Benito Mussolini (1883-1945) was perhaps fascism's most articulate spokesman. He was born the son of a blacksmith and worked as a school teacher and day laborer before becoming editor of a Socialist newspaper prior to World War I. He supported Italy's entry into the war and was wounded in the conflict. In 1919, he was one of many small-time candidates trying to make a mark in Italian politics. An amazing orator and opportunist, Mussolini presented a message of order and action that won him the support of working and middle-class Italians who had been hit hard by the inflation that plagued Europe after the war. Mussolini even organized terrorist squads to contribute to the very instability that drew him adherents. By 1922, the fascists controlled local governments in many cities in northern Italy. Mussolini initiated a march on Rome that met with no resistance from King Victor Emmanuel III. Concerned with violence and his personal safety, the king asked Mussolini to become prime minister and form a government. Although Mussolini had achieved power legally, his Italian National Fascist party ("Blackshirts") did not enjoy even a near majority in the Chamber of Deputies. He immediately disrupted the parliamentary government with threats and physical acts of violence against its elected members. Mussolini was then given temporary dictatorial powers by the king to stabilize the political situation; he soon turned these into a permanent and personal dominance. Mussolini's vision of a "corporate state," in which each individual worked for the welfare of the entire nation, guaranteed employment and satisfactory wages for labor but did not permit strikes.