The Paradoxical Duplexity of Demaratus' Counsel

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Artaxerxes II

Artaxerxes II John Shannahan BAncHist (Hons) (Macquarie University) Thesis submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy. Department of Ancient History, Macquarie University. May, 2015. ii Contents List of Illustrations v Abstract ix Declaration xi Acknowledgements xiii Abbreviations and Conventions xv Introduction 1 CHAPTER 1 THE EARLY REIGN OF ARTAXERXES II The Birth of Artaxerxes to Cyrus’ Challenge 15 The Revolt of Cyrus 41 Observations on the Egyptians at Cunaxa 53 Royal Tactics at Cunaxa 61 The Repercussions of the Revolt 78 CHAPTER 2 399-390: COMBATING THE GREEKS Responses to Thibron, Dercylidas, and Agesilaus 87 The Role of Athens and the Persian Fleet 116 Evagoras the Opportunist and Carian Commanders 135 Artaxerxes’ First Invasion of Egypt: 392/1-390/89? 144 CHAPTER 3 389-380: THE KING’S PEACE AND CYPRUS The King’s Peace (387/6): Purpose and Influence 161 The Chronology of the 380s 172 CHAPTER 4 NUMISMATIC EXPRESSIONS OF SOLIDARITY Coinage in the Reign of Artaxerxes 197 The Baal/Figure in the Winged Disc Staters of Tiribazus 202 Catalogue 203 Date 212 Interpretation 214 Significance 223 Numismatic Iconography and Egyptian Independence 225 Four Comments on Achaemenid Motifs in 227 Philistian Coins iii The Figure in the Winged Disc in Samaria 232 The Pertinence of the Political Situation 241 CHAPTER 5 379-370: EGYPT Planning for the Second Invasion of Egypt 245 Pharnabazus’ Invasion of Egypt and Aftermath 259 CHAPTER 6 THE END OF THE REIGN Destabilisation in the West 267 The Nature of the Evidence 267 Summary of Current Analyses 268 Reconciliation 269 Court Intrigue and the End of Artaxerxes’ Reign 295 Conclusion: Artaxerxes the Diplomat 301 Bibliography 309 Dies 333 Issus 333 Mallus 335 Soli 337 Tarsus 338 Unknown 339 Figures 341 iv List of Illustrations MAP Map 1 Map of the Persian Empire xviii-xix Brosius, The Persians, 54-55 DIES Issus O1 Künker 174 (2010) 403 333 O2 Lanz 125 (2005) 426 333 O3 CNG 200 (2008) 63 333 O4 Künker 143 (2008) 233 333 R1 Babelon, Traité 2, pl. -

Herodotus, Xerxes and the Persian Wars IAN PLANT, DEPARTMENT of ANCIENT HISTORY

Herodotus, Xerxes and the Persian Wars IAN PLANT, DEPARTMENT OF ANCIENT HISTORY Xerxes: Xerxes’ tomb at Naqsh-i-Rustam Herodotus: 2nd century AD: found in Egypt. A Roman copy of a Greek original from the first half of the 4th century BC. Met. Museum New York 91.8 History looking at the evidence • Our understanding of the past filtered through our present • What happened? • Why did it happen? • How can we know? • Key focus is on information • Critical collection of information (what is relevant?) • Critical evaluation of information (what is reliable?) • Critical questioning of information (what questions need to be asked?) • These are essential transferable skills in the Information Age • Let’s look at some examples from Herodotus’ history of the Persian invasion of Greece in 480 BC • Is the evidence from: ― Primary sources: original sources; close to origin of information. ― Secondary sources: sources which cite, comment on or build upon primary sources. ― Tertiary source: cites only secondary sources; does not look at primary sources. • Is it the evidence : ― Reliable; relevant ― Have I analysed it critically? Herodotus: the problem… Succession of Xerxes 7.3 While Darius delayed making his decision [about his successor], it chanced that at this time Demaratus son of Ariston had come up to Susa, in voluntary exile from Lacedaemonia after he had lost the kingship of Sparta. [2] Learning of the contention between the sons of Darius, this man, as the story goes, came and advised Xerxes to add this to what he said: that he had been born when Darius was already king and ruler of Persia, but Artobazanes when Darius was yet a subject; [3] therefore it was neither reasonable nor just that anyone should have the royal privilege before him. -

Marathon 2,500 Years Edited by Christopher Carey & Michael Edwards

MARATHON 2,500 YEARS EDITED BY CHRISTOPHER CAREY & MICHAEL EDWARDS INSTITUTE OF CLASSICAL STUDIES SCHOOL OF ADVANCED STUDY UNIVERSITY OF LONDON MARATHON – 2,500 YEARS BULLETIN OF THE INSTITUTE OF CLASSICAL STUDIES SUPPLEMENT 124 DIRECTOR & GENERAL EDITOR: JOHN NORTH DIRECTOR OF PUBLICATIONS: RICHARD SIMPSON MARATHON – 2,500 YEARS PROCEEDINGS OF THE MARATHON CONFERENCE 2010 EDITED BY CHRISTOPHER CAREY & MICHAEL EDWARDS INSTITUTE OF CLASSICAL STUDIES SCHOOL OF ADVANCED STUDY UNIVERSITY OF LONDON 2013 The cover image shows Persian warriors at Ishtar Gate, from before the fourth century BC. Pergamon Museum/Vorderasiatisches Museum, Berlin. Photo Mohammed Shamma (2003). Used under CC‐BY terms. All rights reserved. This PDF edition published in 2019 First published in print in 2013 This book is published under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial- NoDerivatives (CC-BY-NC-ND 4.0) license. More information regarding CC licenses is available at http://creativecommons.org/licenses/ Available to download free at http://www.humanities-digital-library.org ISBN: 978-1-905670-81-9 (2019 PDF edition) DOI: 10.14296/1019.9781905670819 ISBN: 978-1-905670-52-9 (2013 paperback edition) ©2013 Institute of Classical Studies, University of London The right of contributors to be identified as the authors of the work published here has been asserted by them in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988. Designed and typeset at the Institute of Classical Studies TABLE OF CONTENTS Introductory note 1 P. J. Rhodes The battle of Marathon and modern scholarship 3 Christopher Pelling Herodotus’ Marathon 23 Peter Krentz Marathon and the development of the exclusive hoplite phalanx 35 Andrej Petrovic The battle of Marathon in pre-Herodotean sources: on Marathon verse-inscriptions (IG I3 503/504; Seg Lvi 430) 45 V. -

Archaic Eretria

ARCHAIC ERETRIA This book presents for the first time a history of Eretria during the Archaic Era, the city’s most notable period of political importance. Keith Walker examines all the major elements of the city’s success. One of the key factors explored is Eretria’s role as a pioneer coloniser in both the Levant and the West— its early Aegean ‘island empire’ anticipates that of Athens by more than a century, and Eretrian shipping and trade was similarly widespread. We are shown how the strength of the navy conferred thalassocratic status on the city between 506 and 490 BC, and that the importance of its rowers (Eretria means ‘the rowing city’) probably explains the appearance of its democratic constitution. Walker dates this to the last decade of the sixth century; given the presence of Athenian political exiles there, this may well have provided a model for the later reforms of Kleisthenes in Athens. Eretria’s major, indeed dominant, role in the events of central Greece in the last half of the sixth century, and in the events of the Ionian Revolt to 490, is clearly demonstrated, and the tyranny of Diagoras (c. 538–509), perhaps the golden age of the city, is fully examined. Full documentation of literary, epigraphic and archaeological sources (most of which have previously been inaccessible to an English-speaking audience) is provided, creating a fascinating history and a valuable resource for the Greek historian. Keith Walker is a Research Associate in the Department of Classics, History and Religion at the University of New England, Armidale, Australia. -

The Greek Sources Proceedings of the Groningen 1984 Achaemenid History Workshop Edited by Heleen Sancisi-Weerdenburg and Amélie Kuhrt

Achaemenid History • II The Greek Sources Proceedings of the Groningen 1984 Achaemenid History Workshop edited by Heleen Sancisi-Weerdenburg and Amélie Kuhrt Nederlands Instituut voor het Nabije Oosten Leiden 1987 ACHAEMENID HISTORY 11 THE GREEK SOURCES PROCEEDINGS OF THE GRONINGEN 1984 ACHAEMENID HISTORY WORKSHOP edited by HELEEN SANCISI-WEERDENBURG and AMELIE KUHRT NEDERLANDS INSTITUUT VOOR HET NABIJE OOSTEN LEIDEN 1987 © Copyright 1987 by Nederlands Instituut voor het Nabije Oosten Witte Singe! 24 Postbus 9515 2300 RA Leiden, Nederland All rights reserved, including the right to translate or to reproduce this book or parts thereof in any form CIP-GEGEVENS KONINKLIJKE BIBLIOTHEEK, DEN HAAG Greek The Greek sources: proceedings of the Groningen 1984 Achaemenid history workshop / ed. by Heleen Sancisi-Weerdenburg and Amelie Kuhrt. - Leiden: Nederlands Instituut voor het Nabije Oosten.- (Achaemenid history; II) ISBN90-6258-402-0 SISO 922.6 UDC 935(063) NUHI 641 Trefw.: AchaemenidenjPerzische Rijk/Griekse oudheid; historiografie. ISBN 90 6258 402 0 Printed in Belgium TABLE OF CONTENTS Abbreviations. VII-VIII Amelie Kuhrt and Heleen Sancisi-Weerdenburg INTRODUCTION. IX-XIII Pierre Briant INSTITUTIONS PERSES ET HISTOIRE COMPARATISTE DANS L'HIS- TORIOGRAPHIE GRECQUE. 1-10 P. Calmeyer GREEK HISTORIOGRAPHY AND ACHAEMENID RELIEFS. 11-26 R.B. Stevenson LIES AND INVENTION IN DEINON'S PERSICA . 27-35 Alan Griffiths DEMOCEDES OF CROTON: A GREEKDOCTORATDARIUS' COURT. 37-51 CL Herrenschmidt NOTES SUR LA PARENTE CHEZ LES PERSES AU DEBUT DE L'EM- PIRE ACHEMENIDE. 53-67 Amelie Kuhrt and Susan Sherwin White XERXES' DESTRUCTION OF BABYLONIAN TEMPLES. 69-78 D.M. Lewis THE KING'S DINNER (Polyaenus IV 3.32). -

Mercenaries, Poleis, and Empires in the Fourth Century Bce

The Pennsylvania State University The Graduate School College of the Liberal Arts ALL THE KING’S GREEKS: MERCENARIES, POLEIS, AND EMPIRES IN THE FOURTH CENTURY BCE A Dissertation in History and Classics and Ancient Mediterranean Studies by Jeffrey Rop © 2013 Jeffrey Rop Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy May 2013 ii The dissertation of Jeffrey Rop was reviewed and approved* by the following: Mark Munn Professor of Ancient Greek History and Greek Archaeology, Classics and Ancient Mediterranean Studies Dissertation Advisor Chair of Committee Gary N. Knoppers Edwin Erle Sparks Professor of Classics and Ancient Mediterranean Studies, Religious Studies, and Jewish Studies Garrett G. Fagan Professor of Ancient History and Classics and Ancient Mediterranean Studies Kenneth Hirth Professor of Anthropology Carol Reardon George Winfree Professor of American History David Atwill Associate Professor of History and Asian Studies Graduate Program Director for the Department of History *Signatures are on file in the Graduate School iii ABSTRACT This dissertation examines Greek mercenary service in the Near East from 401- 330 BCE. Traditionally, the employment of Greek soldiers by the Persian Achaemenid Empire and the Kingdom of Egypt during this period has been understood to indicate the military weakness of these polities and the superiority of Greek hoplites over their Near Eastern counterparts. I demonstrate that the purported superiority of Greek heavy infantry has been exaggerated by Greco-Roman authors. Furthermore, close examination of Greek mercenary service reveals that the recruitment of Greek soldiers was not the purpose of Achaemenid foreign policy in Greece and the Aegean, but was instead an indication of the political subordination of prominent Greek citizens and poleis, conducted through the social institution of xenia, to Persian satraps and kings. -

4.2 Empires and Military Glory: Herodotus Relates the Story of Thermopylae

Part 4: Greece and the Hellenistic World 4.2 Empires and Military Glory: Herodotus Relates the Story of Thermopylae Imperialism often goes hand-in-hand with a tradition of martial heroism and a glorification of wartime exploits. In rationalizing their future imperial aspirations, the Greek city-states would often hark back to the deeds of valour during the Persian Wars (490–479 B.C.E.), as in this description of the Spartan stand at the pass of Thermopylae by the historian Herodotus. Source: Bernard Knox, ed.. The Norton Book of Classical Literature (N.Y.: W.W. Norton, 1993), p. 288–293. The Persian army was now close to the pass, and the Greeks, suddenly doubting their power to resist, held a conference to consider the advisability of retreat. It was proposed by the Peloponnesians generally that the army should fall back upon the Peloponnese and hold the Isthmus; but when the Phocians and Locrians expressed their indignation at that sug- gestion, Leonidas gave his voice for staying where they were and sending, at the same time, an appeal for reinforcements to the various states of the confederacy, as their numbers were inadequate to cope with the Persians. During the conference Xerxes sent a man on horseback to ascertain the strength of the Greek force and to observe what the troops were doing. He had heard before he left Thessaly that a small force was concentrated here, led by the Lacedaemonians under Leonidas of the house of Heracles. The Persian rider approached the camp and took a thorough survey of all he could see—which was not, however, the whole Greek army; for the men on the further side of the wall which, after its reconstruction, was now guarded, were out of sight. -

University Microfilms International

ANCIENT EUBOEA: STUDIES IN THE HISTORY OF A GREEK ISLAND FROM EARLIEST TIMES TO 404 B.C. Item Type text; Dissertation-Reproduction (electronic) Authors Vedder, Richard Glen, 1950- Publisher The University of Arizona. Rights Copyright © is held by the author. Digital access to this material is made possible by the University Libraries, University of Arizona. Further transmission, reproduction or presentation (such as public display or performance) of protected items is prohibited except with permission of the author. Download date 11/10/2021 05:15:39 Link to Item http://hdl.handle.net/10150/290465 INFORMATION TO USERS This material was produced from a microfilm copy of the original document. While the most advanced technological means to photograph and reproduce this document have been used, the quality is heavily dependent upon the quality of the original submitted. The following explanation of techniques is provided to help you understand markings or patterns which may appear on this reproduction. 1.The sign or "target" for pages apparently lacking from the document photographed is "Missing Page(s)". If it was possible to obtain the missing page(s) or section, they are spliced into the film along with adjacent pages. This may have necessitated cutting thru an image and duplicating adjacent pages to insure you complete continuity. 2. When an image on the film is obliterated with a large round black mark, it is an indication that the photographer suspected that the copy may have moved during exposure and thus cause a blurred image. You will find a good image of the page in the adjacent frame. -

Three Aspects of Spartan Kingship in Herodotus Rosaria Vignolo Munson

5 Three Aspects of Spartan Kingship in Herodotus Rosaria Vignolo Munson erodotus’ Histories are governed by the rule of resemblance: they explain the nature of a given historical phenomenon by sug gesting similarities to unrelated phenomena entirely different in Hother respects.! We may safely state, in particular, that Herodotus’ analysis of any form of personal power is inseparable from his representation of monarchical rule. This was an essential feature of the foreign culture that threatened the integrity of Hellas at the time of the Persian wars, and it provided the Greeks with a foil for self-definition. The components of the monarchical model in Herodotus have often been discussed,^ and I need only to recall a few points. The speech of Otanes in the Constitutional Debate is the basic theoretical document (3.80). The monarch is here defined as an individual who “can do what he wants without being accountable” (dvevOvvco Trottem ra /SouXerat). When placed in such a position, even the best of men finds himself outside the normal way of thinking (/cat yap av tov aptcTOV avhputv TravTwv (TTavTU e? TavTTjv TTjv apy^v e/cxd? twv ewOoToiv voripdraiv cTTpcreid) and commits many unbearable things (iroWd /cal dracrOaka) out of u/3pts and cpOovos. Typically, the monarch subverts ancestral laws (Ttarpta vopaia), he does violence to women, and he puts people to death without trial. I am happy to dedicate this chapter to Martin Ostwald with gratitude and admiration. 1. The importance of analogical thought in Herodotus is widely recognized. See espe cially the work of Immerwahr (1966) and Lateiner (1989, 191-96). -

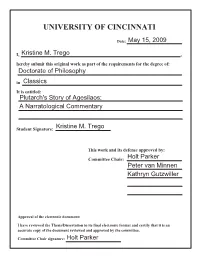

University of Cincinnati

U UNIVERSITY OF CINCINNATI Date: May 15, 2009 I, Kristine M. Trego , hereby submit this original work as part of the requirements for the degree of: Doctorate of Philosophy in Classics It is entitled: Plutarch's Story of Agesilaos; A Narratological Commentary Student Signature: Kristine M. Trego This work and its defense approved by: Committee Chair: Holt Parker Peter van Minnen Kathryn Gutzwiller Approval of the electronic document: I have reviewed the Thesis/Dissertation in its final electronic format and certify that it is an accurate copy of the document reviewed and approved by the committee. Committee Chair signature: Holt Parker Plutarch’s Story of Agesilaos; A Narratological Commentary A dissertation submitted to the Division of Research and Advanced Studies of the University of Cincinnati in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctorate of Philosophy (Ph.D.) in the Department of Classics of the College of Arts and Sciences 2009 by Kristine M. Trego B.A., University of South Florida, 2001 M.A. University of Cincinnati, 2004 Committee Chair: Holt N. Parker Committee Members: Peter van Minnen Kathryn J. Gutzwiller Abstract This analysis will look at the narration and structure of Plutarch’s Agesilaos. The project will offer insight into the methods by which the narrator constructs and presents the story of the life of a well-known historical figure and how his narrative techniques effects his reliability as a historical source. There is an abundance of exceptional recent studies on Plutarch’s interaction with and place within the historical tradition, his literary and philosophical influences, the role of morals in his Lives, and his use of source material, however there has been little scholarly focus—but much interest—in the examination of how Plutarch constructs his narratives to tell the stories they do. -

Sean Manning, a Prosopography of the Followers of Cyrus the Younger

The Ancient History Bulletin VOLUME THIRTY-TWO: 2018 NUMBERS 1-2 Edited by: Edward Anson ò Michael Fronda òDavid Hollander Timothy Howe òJoseph Roisman ò John Vanderspoel Pat Wheatley ò Sabine Müller òAlex McAuley Catalina Balmacedaò Charlotte Dunn ISSN 0835-3638 ANCIENT HISTORY BULLETIN Volume 32 (2018) Numbers 1-2 Edited by: Edward Anson, Catalina Balmaceda, Michael Fronda, David Hollander, Alex McAuley, Sabine Müller, Joseph Roisman, John Vanderspoel, Pat Wheatley Senior Editor: Timothy Howe Assistant Editor: Charlotte Dunn Editorial correspondents Elizabeth Baynham, Hugh Bowden, Franca Landucci Gattinoni, Alexander Meeus, Kurt Raaflaub, P.J. Rhodes, Robert Rollinger, Victor Alonso Troncoso Contents of volume thirty-two Numbers 1-2 1 Sean Manning, A Prosopography of the Followers of Cyrus the Younger 25 Eyal Meyer, Cimon’s Eurymedon Campaign Reconsidered? 44 Joshua P. Nudell, Alexander the Great and Didyma: A Reconsideration 61 Jens Jakobssen and Simon Glenn, New research on the Bactrian Tax-Receipt NOTES TO CONTRIBUTORS AND SUBSCRIBERS The Ancient History Bulletin was founded in 1987 by Waldemar Heckel, Brian Lavelle, and John Vanderspoel. The board of editorial correspondents consists of Elizabeth Baynham (University of Newcastle), Hugh Bowden (Kings College, London), Franca Landucci Gattinoni (Università Cattolica, Milan), Alexander Meeus (University of Leuven), Kurt Raaflaub (Brown University), P.J. Rhodes (Durham University), Robert Rollinger (Universität Innsbruck), Victor Alonso Troncoso (Universidade da Coruña) AHB is currently edited by: Timothy Howe (Senior Editor: [email protected]), Edward Anson, Catalina Balmaceda, Michael Fronda, David Hollander, Alex McAuley, Sabine Müller, Joseph Roisman, John Vanderspoel and Pat Wheatley. AHB promotes scholarly discussion in Ancient History and ancillary fields (such as epigraphy, papyrology, and numismatics) by publishing articles and notes on any aspect of the ancient world from the Near East to Late Antiquity. -

Herodotus and the Beginning of the Ionian Revolt (5.28–38.1) Rosaria Vignolo Munson1

chapter 5 The trouble with the Ionians: Herodotus and the beginning of the Ionian Revolt (5.28–38.1) Rosaria Vignolo Munson1 the larger context Placed at the very centre of Herodotus’ work (5.28–6.42), the Ionian Revolt of 499–494 bc plays a pivotal role, both chronologically and causally, link- ing the Persians’ Eastern campaigns to their invasions of Greece.2 It also represents a crucial moment in Herodotus’ history of the Ionians, which spans the whole work from beginning to end. The Ionians jump-start the Histories, one might say, and they do so because they find themselves at the receiving end of the first known Eastern aggressions against Greeks (1.5.3, 6.2–3). Croesus of Lydia completes ‘the first subjection of Ionia’, as the narrator summarizes at the end of the Croesus logos.3 The second is called ‘enslavement’, when Cyrus defeats Croesus and conquers his possessions.4 And so is the third, which occurs after the failure of the revolt we are examining: oÌtw d t¼ tr©ton ïIwnev katedoulÛqhsan, präton mn Ëp¼ Ludän, dªv d pex¦v t»te Ëp¼ Perswn In this way the Ionians were enslaved for the third time, [having been conquered] first by the Lydians and twice in a row by the Persians. (6.32) The Ionians become free from Persian domination after the Greek victory at the time of Xerxes’ invasion. But the 1-2-3 count in the statement above proleptically alludes to a fourth subjection, beyond the chronological range 1 I thank Carolyn Dewald and Donald Lateiner for reading earlier drafts of this paper and offering suggestions.