Elizabeth De Burgh Lady of Clare

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Tonbridge Castle and Its Lords

Archaeologia Cantiana Vol. 16 1886 TONBRIDGE OASTLE AND ITS LORDS. BY J. F. WADMORE, A.R.I.B.A. ALTHOUGH we may gain much, useful information from Lambard, Hasted, Furley, and others, who have written on this subject, yet I venture to think that there are historical points and features in connection with this building, and the remarkable mound within it, which will be found fresh and interesting. I propose therefore to give an account of the mound and castle, as far as may be from pre-historic times, in connection with the Lords of the Castle and its successive owners. THE MOUND. Some years since, Dr. Fleming, who then resided at the castle, discovered on the mound a coin of Con- stantine, minted at Treves. Few will be disposed to dispute the inference, that the mound existed pre- viously to the coins resting upon it. We must not, however, hastily assume that the mound is of Roman origin, either as regards date or construction. The numerous earthworks and camps which are even now to be found scattered over the British islands are mainly of pre-historic date, although some mounds may be considered Saxon, and others Danish. Many are even now familiarly spoken of as Caesar's or Vespa- sian's camps, like those at East Hampstead (Berks), Folkestone, Amesbury, and Bensbury at Wimbledon. Yet these are in no case to be confounded with Roman TONBEIDGHE CASTLE AND ITS LORDS. 13 camps, which in the times of the Consulate were always square, although under the Emperors both square and oblong shapes were used.* These British camps or burys are of all shapes and sizes, taking their form and configuration from the hill-tops on which they were generally placed. -

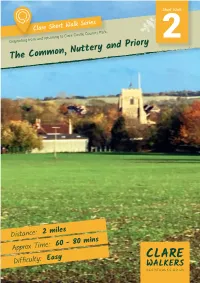

The Common, Nuttery and Priory

Short Walk Clare Short Walk Series Originating from and returning to Clare Castle Country Park. The Common, Nuttery and Priory 2 Distance: 2 miles Approx Time: 60 - 80 mins More walks are available by visiting clarewalks.co.uk or clarecastlecountrypark.co.uk Difficulty: Easy Clare Short Walk 2 Short Walk Series The Clare Short Walks Series is a collection of four overlapping walks aimed at walkers who wish to explore Clare and its surrounds. The walks are all under 2.5 miles and are designed to take between 60 and 80 minutes at a leisurely pace. All the walks originate and end in Clare Castle Country Park. From the car park walk with the ‘Old Goods 4 Follow the path down past the cemetery, Shed’ on your right towards the Station turn right at the bottom and walk around House. Before reaching the house turn left past the field, keeping the field on your right. the moat and, keeping the field on your right, walk along Station Road to the town centre. 5 When you reach a large metal gate, go At the top of Station Road turn right. Cross the through this gate and walk down past Clifton road towards the Co-op and walk along Church Cottages to Stoke Road. Walk across this road Lane, past the Church. and then along Ashen Road. Keep on the right here to face oncoming traffic. Walk across the 2 Cross the High Street, turning right and bridge and then for about 50 metres to the then left through the cemetery gates. -

Clare Castle Monitoring of Masonry Repairs CLA 008

Clare Castle Monitoring of masonry repairs CLA 008 Archaeological Monitoring Report SCCAS Report No. 2012/186 Client: Suffolk County Council Author: David Gill November/2012 © Suffolk County Council Archaeological Service Clare Castle Monitoring of masonry repairs CLA 008 Archaeological Monitoring Report SCCAS Report No. 2012/186 Author: David Gill Contributions By: Illustrator:Crane Begg Editor: Richenda Goffin Report Date: November/2012 HER Information Site Code: CLA 008 Site Name: Clare Castle Report Number 2012/186 Planning Application No: N/A Date of Fieldwork: August-October 2012 Grid Reference: TL 7700 4510 Oasis Reference: c1-138611 Curatorial Officer: Dr Jess Tipper Project Officer: David Gill Client/Funding Body: Suffolk County Council Client Reference: ***************** Digital report submitted to Archaeological Data Service: http://ads.ahds.ac.uk/catalogue/library/greylit Disclaimer Any opinions expressed in this report about the need for further archaeological work are those of the Field Projects Team alone. Ultimately the need for further work will be determined by the Local Planning Authority and its Archaeological Advisors when a planning application is registered. Suffolk County Council’s archaeological contracting services cannot accept responsibility for inconvenience caused to the clients should the Planning Authority take a different view to that expressed in the report. Prepared By: David Gill Date: November 2012 Approved By: Joanna Caruth Position: Senior Project Officer Date: Signed: Contents Summary 1. Introduction 1 2. Site location, geology and topography 3 3. Archaeology and historical background 3 4. Methodology 9 5. Results 9 The castle keep 9 Keep elevations 11 The bailey wall 14 6. Discussion 16 7. Archive deposition 17 8. -

Clare Castle Excavations in 2013

Clare Castle Excavations in 2013 Clare Castle is a medieval motte-and-bailey castle of Norman origin built shortly after the 1066 Conquest by the powerful de Clare family. It was a particularly large and imposing castle by medieval standards, but little of the original structure is visible, much now lost, hidden by trees or damaged by later building, including the 19 th century railway line. In 2013, archaeological excavations by local residents supervised by Access Cambridge Archaeology are exploring four sites within the castle grounds. Little is known of the early history of the site of Clare Castle, but documentary evidence suggests that a small priory was there by 1045 AD, possibly associated with a high-status Anglo-Saxon residence and several human skeletons unearthed in 1951: tooth samples recently subjected to isotopic analysis show the owner to have come from the local area. In 1124 the priory was moved to Stoke-by-Clare. Castles (private defended residences of medieval feudal lords) were introduced to England after the Norman Conquest. Soon after 1066, William the Conqueror granted the Clare estate to one of the knights who’d helped him conquer England, Richard fitz Gilbert. Documents show the castle was built by 1090. Its valley-bottom location is easily defended by the river and strategically positioned to dominate both the adjacent town and movement up and down the valley. If there was an Anglo-Saxon lordly residence on the site, building the castle there would emphasise that power had now passed into new hands. Clare Castle was a motte and bailey castle, the most common form of castle in the 11 th and 12 th centuries which went out of fashion as castles with keeps and curtain walls became popular. -

The Stour Valley Heritage Compendia the Built Heritage Compendium

The Stour Valley Heritage Compendia The Built Heritage Compendium Written by Anne Mason BUILT HERITAGE COMPENDIUM Contents Introduction 5 Background 4 High Status Buildings 5 Churches of the Stour Valley and Dedham Vale 6 Vernacular Buildings 11 The Vernacular Architecture of the Individual Settlements of the Stour Valley and Dedham Vale 18 Conclusion: The Significance of the Built Heritage of the Stour Valley and Dedham Vale 42 Archival Sources for the Built Heritage 43 Bibliography 43 Glossary 44 2 Introduction Buildings are powerful and evocative symbols in the landscape, showing how people have lived and worked in the past. They can be symbols of authority; of opportunity; of new technology, of social class and fluctuations in the local, regional and national economy. Traditional buildings make a major contribution to understanding about how previous generations lived and worked. They also contribute to local character, beauty and distinctiveness as well as providing repositories of local skills and building techniques. Historic buildings are critical to our understanding of settlement patterns and the development of the countryside. Hardly any buildings are as old as the history of a settlement because buildings develop over time as they are extended, rebuilt, refurbished or decay. During the Roman period the population of the Stour Valley increased. The majority of settlements are believed to have been isolated farmsteads along the river valley and particularly at crossing points of the Stour. During the Saxon and medieval periods many of the settlement and field patterns were formed and farmsteads established whose appearance and form make a significant contribution to the landscape character of the Stour Valley. -

HISTORY & ARCHAEOLOGY in the Stour Valley

History & Archaeology in The Stour Valley Dedham Vale Area of Outstanding Natural Beauty (AONB) 1 Clare Castle 3 Melford Hall 4 Kentwell Hall Malting Lane, Clare, CO10 8NW Long Melford, CO10 9AA Long Melford, CO10 9BA www.clarecastlecountrypark.co.uk www.nationaltrust.org.uk/melford-hall www.kentwell.co.uk Stour Valley and surrounding Wool Towns 01787 277902 01787 379228 01787 310207 Stour Valley Path Wool Towns 2 Clare Ancient 5 Long Melford Heritage Centre House Museum Chemist Lane, Long Melford, CO10 9JQ 26 High Street, Clare, CO10 8NY www.suffolkmuseums.org/museums/long-melford-heritage-centre www.clare-ancient-house-museum.co.uk Crown copyright. 01787 277249 7 Lavenham Guildhall 6 Sudbury Heritage Centre Chemist Lane, Long Melford, CO10 9JQ To Bury St Edmunds Town Hall, Sudbury, CO10 2EA www.nationaltrust.org.uk/lavenham-guildhall www.sudburyheritagecentre.co.uk All rights reserved. © Suffolk County Council. Licence LA100023395 Boxted 8 Little Hall Museum Market Place, Lavenham, CO10 9QZ To Newmarket www.suffolkmuseums.org/museums/lavenham -little-hall-museum www.littlehall.org.uk LAVENHAM Great Glemsford Wratting A1141 12 Court Knoll Nayland, CO6 4JL Cavendish www.naylandandwiston.net/history/index.php Kedington To Ipswich CLARE LONG 13 Bridge Cottage HAVERHILL MELFORD 5 Foxearth at Flatford Mill B111 Stoke by Clare Great Flatford Road, East Bergholt, CO7 6UL www.nationaltrust.org.uk/flatford/features/ Sturmer Waldingfield SUDBURY HADLEIGH Steeple Great A1071 Boxford Bumpstead Cornard Bulmer Raydon Information of each location: Polstead To Ipswich 1. Clare Castle 5. Long Melford 10. Bures Dragon Built in the 11th century, Clare Castle has a Heritage Centre Local legends reveal the tale of a knight in the motte and bailey structure. -

Archives Catalogue 16-04-2021 Notes 1 the Catalogue Lists Material Held

Tonbridge Historical Society: Archives Catalogue 16-04-2021 Notes 1 The catalogue lists material held by the Society. It is a work-in-progress. This version was compiled on 16 April 2021. 2 All codes should be prefixed by THS/ 3 Codes given in square brackets in some entries refer to former numbering schemes, now obsolete. 4 The catalogue is in three sections: Section 1 – Material organised by content thus: B: Business, Trade and Industry B/01 Trade B/02 Professions B/03 Cattle Market B/04 Manufacturing/Industry B/05 Chamber of Trade B/06 Banking E: Estate and property E/01 - E/50 H: Town History H/01 Books and pamphlets H/02 Newspapers H/03 Prints H/04 People and families H/05 World War I and II memorabilia H/06 Houses and buildings H/07 Local history research H/08 Folded Maps H/09 Royal Visits H/10 War memorials H/11 Rolled maps and plans H/12 Politics H/13 Archaeological Reports LG: Local Government LG/01 Wartime measures LG/02 Local Board LG/03 TUDC LG/04 Parish Vestry LG/05 Ad Hoc Organisations LG/06 TMBC LG/07 see below (Plans) LG/08 ?Manor Court LG/09 Cottage Hospital (Queen Victoria C H) Q: Charity and Education Q/ADU Adult Education /01 Adult School Union Q/CHA Charities /01 William Strong’s Charity /02 Elizabeth Clarke’s Charity /03 Sir Thomas Smythe’s Charity /04 Petley and Deakin’s Almshouses 1 /06 War Relief Fund Q/GEN General Charity and Education Q/INF Infant Schools /01/ Wesleyan Infants’ School Q/PRI Primary/Elementary Schools /01 St Stephen’s Schools /02 National School /03 Hildenborough CE. -

Western Approaches: the Original Entrance Front of Caerphilly Castle?

Western Approaches: The original entrance front of Caerphilly Castle? Derek Renn Fig. 1. Caerphilly castle. The Western approach - (or Western Island, the hornwork) leading to the Central Island through the west outer and inner gates. Image © Paul R Davis THE CASTLE STUDIES G UP THEU NAL CASTLE N 29 210 STUDIES 2015-16 G UP U NAL N 31 2017-18 Western Approaches: The original entrance front of Caerphilly Castle ? Western Approaches: The original entrance mention in 1307 [IPM of Gilbert de Clare's wid- front of Caerphilly Castle ? ow] of both the pasture of the road before the 4 Derek Renn gate of the castle, and….’. ABSTRACT In 2000, Rees’ ‘possibility’ became a probability when the Royal Commission on the Ancient and That Caerphilly Castle was originally planned to Historical Monuments of Wales’ report on the be approached from the west is not a new castle stated: ‘At first, it appears that the main theory, but is here examined in depth. There approach to the castle was from the W. through may have been a pre-castle settlement on the the unfinished outwork [ie. the Western Island], site. It is proposed that the Inner West gate- which may explain the apparent priority given house (and a possible hall-and-chamber) were to the fine Inner West Gatehouse. Both inner adapted when the Inner East gatehouse was gatehouses are impressive, but that to the west planned. The probable date of the similar Ton- is less developed and presumably the earlier’.5 bridge gatehouse is reviewed in the light of the John Owen, a local resident, argued in 2000 that career of Roger de Leyburn. -

Clare Castle Excavations, 1955

CLARE CASTLE EXCAVATIONS, 1955 By GROUP CAPTAIN G. M. KNOCKER Consequent upon the decision of the Clare Rural District Council to run a sewer trench across the northern bailey of Clare Castle, part of a general sewerage scheme covering the whole town, the writer was instructed to keep a watch over the excava- tions and report any interesting discoveriesto the Chief Inspector of Ancient Monuments, Ministry of Works. This duty was carried out at intervals between 5 June and 4 August, 1955.1 HISTORY2 Of the Castle nothing now remains except the motte, the northern bank of the inner bailey, with fragments of its curtain wall and the northern and eastern banks of the northern bailey. The main castle buildings have disappeared, most of the inner bailey being occupied by the railway station. The present layout is shown in Fig. 17, forming part of the 25-inch map O.S. Suffolk Sheet LXXI.7 and EssexSheet V.7. Little is known, says Mrs. Ward, of Clare before the Norman Conquest. There is evidenceofa Roman Camp near the Danepits and it is thought that the northern bailey was part of an Anglo- Saxon fortificationat the time of the Conquest when Earl Aluric held the town.3 (The present very limited excavations,however, did little to justify this belief,no Saxon pottery being found within the northern bailey, with the possible exception of Fig. 20.1). 1 The thanks of the writer are due to Mr. G. C. Bickerton, Resident Engineer, Clare R.D.C., Messrs. A. Patterson and M. W. Dyer of Messrs. -

Clare Castle, Suffolk

Shell-keeps - The Catalogue Fig. 1. Clare Castle, Suffolk. The fragmentary remains of the shell-keep from the south. The castle now lies in the Clare Castle Country Park. The inner bailey was purchased by the Great Eastern Railway and Clare station, track and sidings were open from 1865 until 1967. Much of this railway archaeology remains. Clare 5. Clare in the late-13th or 14th century. This took the form of Clare Castle is a motte and bailey castle first a polygonal shell, with (presumed) fourteen integral documented in 1090, and probably built by Richard triangular buttresses (of which three remain) FitzGilbert (before 1035 - c. 1090), yet it appears to supporting a 6ft (1.8m) thick wall. The inner bailey have gone out of use by the middle of the 15th century. was strengthened with new stone walls, 20 to 30 feet Richard FitzGilbert (styled de Clare) was granted a (6 to 9m) tall on top of the earlier earthen banks, the barony by William the Conqueror, with two blocks of walls and shell keep being built of flint and rubble. land, first in Kent and later across Suffolk and Essex. Another section of wall east of the motte protected Richard built two castles to defend his new lands, the steps up to the shell keep. Both walls were Tonbridge in Kent, followed by Clare Castle in part-restored in the 19th century, when the present Suffolk. The total castle area was unusually large, with spiral path up the castle mound was also built. In 1846 two baileys, rather than the usual one, and a 100 ft the motte was still separated from the inner bailey by (30m) high motte. -

T ESTATES OP TE GLARE FAMILY, 1066-1317 Jennifer Clare W&Rd

T ESTATES OP TE GLARE FAMILY, 1066-1317 Jennifer Clare W&rd. Q7 17DEC1962 .2 THE ESTATP OP THE CURE FANILY, 1066 - 1317. ABSTRACT Throughout the early Middle Ages, the Clare earls of Hertford and. Gloucester were prominent figures on the political scene. Their position as baronial leaders was derived from their landed wealth, and was built up gradually over two hundred and fifty years. Richard I de Clare arrived in England in 1066 as a Norman adventurer, and was granted the honours of Tonbridge and Clare. The family more than doubled its laths during the twelfth and thirteenth centuries, mainly by inheritance, the greatest acquisition being the honour of Gloucester in 1217. Only in the first half of the twelfth century was the honour an autonomous unit. In the honour of Clare, the earls relied on their own tenants as officials in the twelfth century, but in the thirteenth the administration was professional and bureaucratic. The earl's relations with his sub-tenants are unknown before the early fourteenth century; then, in contrast to other estates, the Clare honour-court was busy, strong and fairly efficient. In contrast to the honours of Clare and Gloucester, held of the king in chief, Tonbridge was held of the archbishop of Canterbury, and the relationship between archbishop and earl was the subject of several disputes. As to franchises, the earl exercised the highest which he possessed in England at Tonbridge; elsewhere he appropriated franchises on a large scale during the Barons' Wars of 1258-1265, but most of these were surrendered as a result of Edward I's quo warranto proceedings. -

The Family of Clare

Archaeological Journal ISSN: 0066-5983 (Print) 2373-2288 (Online) Journal homepage: http://www.tandfonline.com/loi/raij20 The Family of Clare J. H. Round M.A. To cite this article: J. H. Round M.A. (1899) The Family of Clare, Archaeological Journal, 56:1, 221-231, DOI: 10.1080/00665983.1899.10852822 To link to this article: http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/00665983.1899.10852822 Published online: 16 Jul 2014. Submit your article to this journal Article views: 2 View related articles Full Terms & Conditions of access and use can be found at http://www.tandfonline.com/action/journalInformation?journalCode=raij20 Download by: [University of Exeter] Date: 18 June 2016, At: 17:10 THE FAMILY OF CLARE. By J. H. ROUND, Μ .A. It is now more than twelve years since I wrote for the Dictionary of National Biography five articles on the house of Clare, one of them dealing with the family as a whole, and four others with members of the house who flourished in the Norman period. Having, since then, further studied its early ramifications, I propose to touch on certain points to which I have given special attention in the history of " a house which played," to quote Mr. Freeman's words, "so great a part alike in England, Wales and Ireland." A Suffolk Congress of the Institute is an eminently suit- able occasion on which to deal with the family of Clare, which derived its name from the great stronghold that the Institute is about to visit, and the founder of which obtained in Suffolk so vast a fief at the Conquest.