Archaeological Excavations at Clare Castle, Clare, Suffolk, 2013

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Our Castle, Our Town

Our Castle, Our Town An n 2011 BACAS took part in a community project undertaken by Castle Cary investigation Museum with the purpose of exploring a selection of historic sites in and around into the the town of Castle Cary. archaeology of I Castle Cary's Using a number of non intrusive surveying methods including geophysical survey Castle site and aerial photography, the aim of the project was to develop the interpretation of some of the town’s historic sites, including the town’s castle site. A geophysical Matthew survey was undertaken at three sites, including the Castle site, the later manorial Charlton site, and a small survey 2 km south west of Castle Cary, at Dimmer. The focus of the article will be the main castle site centred in the town (see Figure 1) which will provide a brief history of the site, followed by the results of the survey and subsequent interpretation. Location and Topography Castle Cary is a small town in south east Somerset, lying within the Jurassic belt of geology, approximately at the junction of the upper lias and the inferior and upper oolites. Building stone is plentiful, and is orange to yellow in colour. This is the source of the River Cary, which now runs to the Bristol Channel via King’s Sedgemoor Drain and the River Parrett, but prior to 1793 petered out within Sedgemoor. The site occupies a natural spur formed by two conjoining, irregularly shaped mounds extending from the north east to the south west. The ground gradually rises to the north and, more steeply, to the east, and falls away to the south. -

An Excavation in the Inner Bailey of Shrewsbury Castle

An excavation in the inner bailey of Shrewsbury Castle Nigel Baker January 2020 An excavation in the inner bailey of Shrewsbury Castle Nigel Baker BA PhD FSA MCIfA January 2020 A report to the Castle Studies Trust 1. Shrewsbury Castle: the inner bailey excavation in progress, July 2019. North to top. (Shropshire Council) Summary In May and July 2019 a two-phase archaeological investigation of the inner bailey of Shrewsbury Castle took place, supported by a grant from the Castle Studies Trust. A geophysical survey by Tiger Geo used resistivity and ground-penetrating radar to identify a hard surface under the north-west side of the inner bailey lawn and a number of features under the western rampart. A trench excavated across the lawn showed that the hard material was the flattened top of natural glacial deposits, the site having been levelled in the post-medieval period, possibly by Telford in the 1790s. The natural gravel was found to have been cut by a twelve-metre wide ditch around the base of the motte, together with pits and garden features. One pit was of late pre-Conquest date. 1 Introduction Shrewsbury Castle is situated on the isthmus, the neck, of the great loop of the river Severn containing the pre-Conquest borough of Shrewsbury, a situation akin to that of the castles at Durham and Bristol. It was in existence within three years of the Battle of Hastings and in 1069 withstood a siege mounted by local rebels against Norman rule under Edric ‘the Wild’ (Sylvaticus). It is one of the best-preserved Conquest-period shire-town earthwork castles in England, but is also one of the least well known, no excavation having previously taken place within the perimeter of the inner bailey. -

Tonbridge Castle and Its Lords

Archaeologia Cantiana Vol. 16 1886 TONBRIDGE OASTLE AND ITS LORDS. BY J. F. WADMORE, A.R.I.B.A. ALTHOUGH we may gain much, useful information from Lambard, Hasted, Furley, and others, who have written on this subject, yet I venture to think that there are historical points and features in connection with this building, and the remarkable mound within it, which will be found fresh and interesting. I propose therefore to give an account of the mound and castle, as far as may be from pre-historic times, in connection with the Lords of the Castle and its successive owners. THE MOUND. Some years since, Dr. Fleming, who then resided at the castle, discovered on the mound a coin of Con- stantine, minted at Treves. Few will be disposed to dispute the inference, that the mound existed pre- viously to the coins resting upon it. We must not, however, hastily assume that the mound is of Roman origin, either as regards date or construction. The numerous earthworks and camps which are even now to be found scattered over the British islands are mainly of pre-historic date, although some mounds may be considered Saxon, and others Danish. Many are even now familiarly spoken of as Caesar's or Vespa- sian's camps, like those at East Hampstead (Berks), Folkestone, Amesbury, and Bensbury at Wimbledon. Yet these are in no case to be confounded with Roman TONBEIDGHE CASTLE AND ITS LORDS. 13 camps, which in the times of the Consulate were always square, although under the Emperors both square and oblong shapes were used.* These British camps or burys are of all shapes and sizes, taking their form and configuration from the hill-tops on which they were generally placed. -

Portchester Castle Student Activity Sheets

STUDENT ACTIVITY SHEETS Portchester Castle This resource has been designed to help students step into the story of Portchester Castle, which provides essential insight into over 1,700 years of history. It was a Roman fort, a Saxon stronghold, a royal castle and eventually a prison. Give these activity sheets to students on site to help them explore Portchester Castle. Get in touch with our Education Booking Team: 0370 333 0606 [email protected] https://bookings.english-heritage.org.uk/education Don’t forget to download our Hazard Information Sheets and Discovery Visit Risk Assessments to help with planning: • In the Footsteps of Kings • Big History: From Dominant Castle to Hidden Fort Share your visit with us @EHEducation The English Heritage Trust is a charity, no. 1140351, and a company, no. 07447221, registered in England. All images are copyright of English Heritage or Historic England unless otherwise stated. Published July 2017 Portchester Castle is over 1,700 years old! It was a Roman fort, a Saxon stronghold, a royal palace and eventually a prison. Its commanding location means it has played a major part in defending Portsmouth Harbour EXPLORE and the Solent for hundreds of years. THE CASTLE DISCOVER OUR TOP 10 Explore the castle in small groups. THINGS TO SEE Complete the challenges to find out about Portchester’s exciting past. 1 ROMAN WALLS These walls were built between AD 285 and 290 by a Roman naval commander called Carausius. He was in charge of protecting this bit of the coast from pirate attacks. The walls’ core is made from layers of flint, bonded together with mortar. -

Castelli Di Bellinzona

Trenino Artù -design.net Key Escape Room Torre Nera La Torre Nera di Castelgrande vi aspetta per vivere una entusiasmante espe- rienza e un fantastico viaggio nel tempo! Codici, indizi e oggetti misteriosi che vi daranno la libertà! Una Room ambientata in una location suggestiva, circondati da 700 anni di storia! Prenotate subito la vostra avventura medievale su www.blockati.ch Escape Room Torre Nera C Im Turm von Castelgrande auch “Torre Nera” genannt, kannst du ein aufre- gendes Erlebnis und eine unglaubliche Zeitreise erleben! Codes, Hinweise M und mysteriöse Objekte entschlüsseln, die dir die Freiheit geben! Ein Raum in Y einer anziehender Lage, umgeben von 700 Jahren Geschichte! CM Buchen Sie jetzt Ihr mittelalterliches Abenteuer auf www.blockati.ch MY Escape Room Tour Noire CY La Tour Noire de Castelgrande, vous attends pour vivre une expérience pas- CMY sionnante et un voyage fantastique dans le temps ! Des codes, des indices et des objets mystérieux vous donneront la liberté! Une salle dans un lieu Preise / Prix / Prices Orari / Fahrplan / Horaire / Timetable K évocateur, entouré de 700 ans d’histoire ! Piazza Collegiata Partenza / Abfahrt / Lieu de départ / Departure Réservez votre aventure médiévale dès maintenant sur www.blockati.ch Trenino Artù aprile-novembre Do – Ve / So – Fr / Di – Ve / Su – Fr 10.00 / 11.20 / 13.30 / 15.00 / 16.30 Adulti 12.– Piazza Governo Partenza / Abfahrt / Lieu de départ / Departure Escape Room Black Tower Sa 11.20 / 13.30 The Black Tower of Castelgrande, to live an exciting experience and a fan- Ridotti Piazza Collegiata Partenza / Abfahrt / Lieu de départ / Departure tastic journey through time! Codes, clues and mysterious objects that will Senior (+65), studenti e ragazzi 6 – 16 anni 10.– Sa 15.00 / 16.30 give you freedom! A Room set in an evocative location, surrounded by 700 a Castelgrande, years of history! Gruppi (min. -

Tarbert Castle

TARBERT CASTLE EXCAVATION PROJECT DESIGN March 2018 Roderick Regan Tarbert Castle: Our Castle of Kings A Community Archaeological Excavation. Many questions remain as to the origin of Tarbert castle, its development and its layout, while the function of many of its component features remain unclear. Also unclear is whether the remains of medieval royal burgh extend along the ridge to the south of the castle. A programme of community archaeological excavation would answer some of these questions, leading to a better interpretation, presentation and future protection of the castle, while promoting the castle as an important place through generated publicity and the excitement of local involvement. Several areas within the castle itself readily suggest areas of potential investigation, particularly the building ranges lining the inner bailey and the presumed entrance into the outer bailey. Beyond the castle to the south are evidence of ditches and terracing while anomalies detected during a previous geophysical survey suggest further fruitful areas of investigation, which might help establish the presence of the putative medieval burgh. A programme of archaeology involving the community of Tarbert would not only shed light on this important medieval monument but would help to ensure it remained a ‘very centrical place’ in the future. Kilmartin Museum Argyll, PA31 8RQ Tel: 01546 510 278 Email: http://www.kilmartin.org © 2018 Kilmartin Museum Company Ltd SC 022744. Kilmartin House Trading Co. Ltd. SC 166302 (Scotland) ii Contents 1. Introduction 1 2. Tarbert Castle 5 2.1 Location and Topography 5 2.2 Historical Background 5 3 Archaeological and Background 5 3.1 Laser Survey 6 3.2 Geophysical Survey 6 3.3 Ground and Photographic Survey 6 3.4 Excavation 7 3.5 Watching Brief 7 3.6 Recorded Artefacts 7 4. -

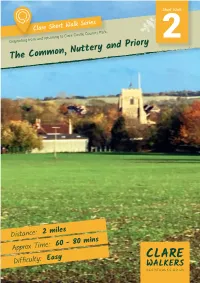

The Common, Nuttery and Priory

Short Walk Clare Short Walk Series Originating from and returning to Clare Castle Country Park. The Common, Nuttery and Priory 2 Distance: 2 miles Approx Time: 60 - 80 mins More walks are available by visiting clarewalks.co.uk or clarecastlecountrypark.co.uk Difficulty: Easy Clare Short Walk 2 Short Walk Series The Clare Short Walks Series is a collection of four overlapping walks aimed at walkers who wish to explore Clare and its surrounds. The walks are all under 2.5 miles and are designed to take between 60 and 80 minutes at a leisurely pace. All the walks originate and end in Clare Castle Country Park. From the car park walk with the ‘Old Goods 4 Follow the path down past the cemetery, Shed’ on your right towards the Station turn right at the bottom and walk around House. Before reaching the house turn left past the field, keeping the field on your right. the moat and, keeping the field on your right, walk along Station Road to the town centre. 5 When you reach a large metal gate, go At the top of Station Road turn right. Cross the through this gate and walk down past Clifton road towards the Co-op and walk along Church Cottages to Stoke Road. Walk across this road Lane, past the Church. and then along Ashen Road. Keep on the right here to face oncoming traffic. Walk across the 2 Cross the High Street, turning right and bridge and then for about 50 metres to the then left through the cemetery gates. -

Elizabeth De Burgh Lady of Clare

http://kentarchaeology.org.uk/research/archaeologia-cantiana/ Kent Archaeological Society is a registered charity number 223382 © 2017 Kent Archaeological Society ELIZABETH DE BURGH, LADY OF CLARE (1295-1360): THE LOGISTICS OF HER PILGRIMAGES TO CANTERBURY JENNIFER WARD Pilgrimage in the Middle Ages was regarded as an integral part of religious practice. The best known pilgrims to Canterbury are those of Chaucer's Canterbury Tales, enjoying each other's company and telling their stories as they journeyed to the shrine of St Thomas Becket. Chaucer chose his pilgrims from a broad spectrum of society. Many people, rich and poor, visited local as well as the major shrines in England, and travelled abroad, as did the Wife of Bath and Margery Kempe, to visit the shrines at Cologne, Santiago de Compostella, Rome and Jerusalem. Their journeys are recorded in their own and others' accounts. What is less well known are the accounts of pilgrimages in royal and noble household documents which record the preparations, the journey itself, provisioning and transport. Some also record the religious dimension of the pilgrimage, the visits and offerings to shrines, and details of prayers and masses. Elizabeth de Burgh, Lady of Clare, was a member of the higher nobility; she was the youngest daughter of Gilbert de Clare, earl of Gloucester and Hertford (d.1295), sister of the last Gilbert de Clare, earl of Gloucester, yvho was killed at Bannockburn in 1314, and cousin of Edward III.1 Three years after her brother's death, she and her two elder sisters inherited equal shares of the Clare lands in England, Wales and Ireland which were valued at c.£6,000 a year.2 Elizabeth's share lay mainly in East Anglia, with Clare castle (Suffolk) as Uie administrative centre and principal residence; she came to style herself Lady of Clare, and she was refened to in her records as the Lady. -

Kenilworth Castle

Student Booklet Kenilworth Castle 1 Introduction and Overview We hope you have been lucky enough to visit this historic site but even if you have not, we hope this guide will help you to really understand the castle and how it developed over time. Where is Kenilworth Castle? The castle and landscape: Aerial view of the castle, mere and surrounding landscape. 2 What is the layout of Kenilworth Castle? Castle Plan 3 Key Phases 1100s Kenilworth under the De Clintons 1120-1174 Kenilworth as a royal fortress 1174-1244 1200s Kenilworth under Simon de Montfort 1244-65 Kenilworth under the House of Lancaster 1266-136 1300s Kenilworth under John of Gaunt 1361-99 1400s Kenilworth under the Lancastrians and the Tudors 1399-1547 1500s Kenilworth under the Dudley family 1547-88 1600s Kenilworth under the Stuarts 1612-65 1700s Kenilworth under the Hydes 1665-1700s Activity 1. Make your own copy of this timeline on a sheet of A4 paper. Just mark in the seven main phases. As you read through this guide add in details of the development of the castle. This timeline will probably become a bit messy but don’t worry! Keep it safe and at the end of the guide we will give you some ideas on how to summarise what you have learned. 2. There are seven periods of the castle's history listed in the timeline. Some of the English Heritage experts came up with titles for five of the periods of the castle's history: • An extraordinary palace • A stunning place of entertainment • A castle fit for kings • A formidable fortress • A royal stronghold 3. -

Clare Castle Monitoring of Masonry Repairs CLA 008

Clare Castle Monitoring of masonry repairs CLA 008 Archaeological Monitoring Report SCCAS Report No. 2012/186 Client: Suffolk County Council Author: David Gill November/2012 © Suffolk County Council Archaeological Service Clare Castle Monitoring of masonry repairs CLA 008 Archaeological Monitoring Report SCCAS Report No. 2012/186 Author: David Gill Contributions By: Illustrator:Crane Begg Editor: Richenda Goffin Report Date: November/2012 HER Information Site Code: CLA 008 Site Name: Clare Castle Report Number 2012/186 Planning Application No: N/A Date of Fieldwork: August-October 2012 Grid Reference: TL 7700 4510 Oasis Reference: c1-138611 Curatorial Officer: Dr Jess Tipper Project Officer: David Gill Client/Funding Body: Suffolk County Council Client Reference: ***************** Digital report submitted to Archaeological Data Service: http://ads.ahds.ac.uk/catalogue/library/greylit Disclaimer Any opinions expressed in this report about the need for further archaeological work are those of the Field Projects Team alone. Ultimately the need for further work will be determined by the Local Planning Authority and its Archaeological Advisors when a planning application is registered. Suffolk County Council’s archaeological contracting services cannot accept responsibility for inconvenience caused to the clients should the Planning Authority take a different view to that expressed in the report. Prepared By: David Gill Date: November 2012 Approved By: Joanna Caruth Position: Senior Project Officer Date: Signed: Contents Summary 1. Introduction 1 2. Site location, geology and topography 3 3. Archaeology and historical background 3 4. Methodology 9 5. Results 9 The castle keep 9 Keep elevations 11 The bailey wall 14 6. Discussion 16 7. Archive deposition 17 8. -

ISABEL DE BEAUMONT, DUCHESS of LANCASTER (C.1318-C.1359) by Brad Verity1

THE FIRST ENGLISH DUCHESS -307- THE FIRST ENGLISH DUCHESS: ISABEL DE BEAUMONT, DUCHESS OF LANCASTER (C.1318-C.1359) by Brad Verity1 ABSTRACT This article covers the life of Isabel de Beaumont, wife of Henry of Grosmont, Duke of Lancaster. Her parentage and chronology, and her limited impact on the 14th century English court, are explored, with emphasis on correcting the established account of her death. It will be shown that she did not survive, but rather predeceased, her husband. Foundations (2004) 1 (5): 307-323 © Copyright FMG Henry of Grosmont (c.1310-1361), Duke of Lancaster, remains one of the most renowned figures of 14th century England, dominating the military campaigns and diplomatic missions of the first thirty years of the reign of Edward III. By contrast, his wife, Isabel ― the first woman in England to hold the title of duchess ― hides in the background of the era, vague to the point of obscurity. As Duke Henry’s modern biographer, Kenneth Fowler (1969, p.215), notes, “in their thirty years of married life she hardly appears on record at all.” This is not so surprising when the position of English noblewomen as wives in the 14th century is considered – they were in all legal respects subordinate to their husbands, expected to manage the household, oversee the children, and be religious benefactresses. Duchess Isabel was, in that mould, very much a woman of her time, mentioned in appropriate official records (papal dispensation requests, grants that affected lands held in jointure, etc.) only when necessary. What is noteworthy, considering the vast estates of the Duchy of Lancaster and her prominent social position as wife of the third man in England (after the King and the Black Prince), is her lack of mention in contemporary chronicles. -

Clare Castle Excavations in 2013

Clare Castle Excavations in 2013 Clare Castle is a medieval motte-and-bailey castle of Norman origin built shortly after the 1066 Conquest by the powerful de Clare family. It was a particularly large and imposing castle by medieval standards, but little of the original structure is visible, much now lost, hidden by trees or damaged by later building, including the 19 th century railway line. In 2013, archaeological excavations by local residents supervised by Access Cambridge Archaeology are exploring four sites within the castle grounds. Little is known of the early history of the site of Clare Castle, but documentary evidence suggests that a small priory was there by 1045 AD, possibly associated with a high-status Anglo-Saxon residence and several human skeletons unearthed in 1951: tooth samples recently subjected to isotopic analysis show the owner to have come from the local area. In 1124 the priory was moved to Stoke-by-Clare. Castles (private defended residences of medieval feudal lords) were introduced to England after the Norman Conquest. Soon after 1066, William the Conqueror granted the Clare estate to one of the knights who’d helped him conquer England, Richard fitz Gilbert. Documents show the castle was built by 1090. Its valley-bottom location is easily defended by the river and strategically positioned to dominate both the adjacent town and movement up and down the valley. If there was an Anglo-Saxon lordly residence on the site, building the castle there would emphasise that power had now passed into new hands. Clare Castle was a motte and bailey castle, the most common form of castle in the 11 th and 12 th centuries which went out of fashion as castles with keeps and curtain walls became popular.