Old-Guard-Williamsburg.Pdf

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Frontiers of American Grand Strategy: Settlers, Elites, and the Standing Army in America’S Indian Wars

THE FRONTIERS OF AMERICAN GRAND STRATEGY: SETTLERS, ELITES, AND THE STANDING ARMY IN AMERICA’S INDIAN WARS A Dissertation submitted to the Faculty of the Graduate School of Arts and Sciences of Georgetown University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Government By Andrew Alden Szarejko, M.A. Washington, D.C. August 11, 2020 Copyright 2020 by Andrew Alden Szarejko All Rights Reserved ii THE FRONTIERS OF AMERICAN GRAND STRATEGY: SETTLERS, ELITES, AND THE STANDING ARMY IN AMERICA’S INDIAN WARS Andrew Alden Szarejko, M.A. Thesis Advisor: Andrew O. Bennett, Ph.D. ABSTRACT Much work on U.S. grand strategy focuses on the twentieth and twenty-first centuries. If the United States did have a grand strategy before that, IR scholars often pay little attention to it, and when they do, they rarely agree on how best to characterize it. I show that federal political elites generally wanted to expand the territorial reach of the United States and its relative power, but they sought to expand while avoiding war with European powers and Native nations alike. I focus on U.S. wars with Native nations to show how domestic conditions created a disjuncture between the principles and practice of this grand strategy. Indeed, in many of America’s so- called Indian Wars, U.S. settlers were the ones to initiate conflict, and they eventually brought federal officials into wars that the elites would have preferred to avoid. I develop an explanation for settler success and failure in doing so. I focus on the ways that settlers’ two faits accomplis— the act of settling on disputed territory without authorization and the act of initiating violent conflict with Native nations—affected federal decision-making by putting pressure on speculators and local elites to lobby federal officials for military intervention, by causing federal officials to fear that settlers would create their own states or ally with foreign powers, and by eroding the credibility of U.S. -

Issue 133:Layout 1 7/21/2011 10:44 PM Page 1 I Ancienttimes Published by the Company of Fifers & Drummers, Inc

Issue 133:Layout 1 7/21/2011 10:44 PM Page 1 i AncientTimes Published by the company of Fifers & Drummers, Inc. summer 2011 Issue 133 $5.00 In thIs Issue: MusIc & ReenactIng usaRD conventIon the gReat WesteRn MusteR Issue 133:Layout 1 7/21/2011 10:45 PM Page 2 w. Alboum HAt Co. InC. presents Authentic Fife and Drum Corps Hats For the finest quality headwear you can buy. Call or Write: (973)-371-9100 1439 Springfield Ave, Irvington, nJ 07111 C.P. Burdick & Son, Inc. IMPoRtant notIce Four Generations of Warmth When your mailing address changes, Fuel Oil/excavation Services please notify us promptly! 24-Hour Service 860-767-8402 The Post Office does not advise us. Write: Membership Committee Main Street, Ivoryton P.O. Box 227, Ivoryton, CT 06442-0227 Connecticut 06442 or email: membership@companyoffife - anddrum.org HeAly FluTe COMPAny Skip Healy Fife & Flute Maker Featuring hand-crafted instruments of the finest quality. Also specializing in repairs and restoration of modern and wooden Fifes and Flutes On the web: www.skiphealy.com Phone/Fax: (401) 935-9365 email: [email protected] 5 Division Street Box 2 3 east Greenwich, RI 02818 Issue 133:Layout 1 7/21/2011 10:45 PM Page 3 Ancient times 2 Issue 133, Summer 2011 1 Fifes, Drums, & Reen - 5 Published by acting: A Wande ring The Company of Dilettante Looks for Fifers & Drummers Common Ground FRoM the eDItoR http :/ / companyoffifeanddrum.org u editor: Deirdre Sweeney 4 art & Design Director: Deirdre Sweeney Let’s Get the Music advertising Manager: t Deep River this year a Robert Kelsey Right s 14 brief, quiet lull settled in contributing editor: Bill Maling after the jam session Illustrator: Scott Baldwin 5 A Membership/subscriptions: s dispersed, and some musicians For corps, individual, or life membership infor - Book Review: at Taggarts were playing one of mation or institutional subscriptions: Dance to the Fiddle, Attn: Membership The Company of Fifers & those exquisitely grave and un - I Drummers P.O. -

A Study of Percussion Pedagogical Texts and a Percussion Primer Nathaniel Gworek University of Connecticut - Storrs, [email protected]

University of Connecticut OpenCommons@UConn Doctoral Dissertations University of Connecticut Graduate School 4-7-2017 A Study of Percussion Pedagogical Texts and a Percussion Primer Nathaniel Gworek University of Connecticut - Storrs, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://opencommons.uconn.edu/dissertations Recommended Citation Gworek, Nathaniel, "A Study of Percussion Pedagogical Texts and a Percussion Primer" (2017). Doctoral Dissertations. 1388. https://opencommons.uconn.edu/dissertations/1388 A Study of Percussion Pedagogical Texts and a Percussion Primer Nathaniel Richard Gworek, DMA University of Connecticut, 2017 My dissertation project is in two parts; the first part examines and evaluates percussion pedagogical literature from the past century, while the second is a percussion primer of my own authorship. The primer, which assumes a basic knowledge of standard musical notation, provide a structured system of teaching and learning percussion technique; it is supplemented with videos to utilize current technology as an educational resource. Many percussion method books have a narrow focus on only one instrument. There are few comprehensive resources that address the entire family of instruments, but they generally cater to a college level audience. My research focuses on the layout of the comprehensive resources while utilizing the narrow sources to inform my exercises. This research helped me find a middle ground, providing the technical development of the narrow focus resources while covering the breadth of topics in the comprehensive resources. This, in turn, help me develop an informationally inclusive yet concise resource for instructors and for students of all ages. My primer contain lessons on snare drum, timpani, and mallet percussion, and complementary instruments, such as bass drum, triangle, and cymbals. -

Pat a Pan Fife and Drum Corps Sheet Music

Pat A Pan Fife And Drum Corps Sheet Music Download pat a pan fife and drum corps sheet music pdf now available in our library. We give you 1 pages partial preview of pat a pan fife and drum corps sheet music that you can try for free. This music notes has been read 3367 times and last read at 2021-09-28 08:10:20. In order to continue read the entire sheet music of pat a pan fife and drum corps you need to signup, download music sheet notes in pdf format also available for offline reading. Instrument: Drums, Flute, Percussion Ensemble: Drum And Bugle Corps Level: Beginning [ READ SHEET MUSIC ] Other Sheet Music With A Fife And Drum With A Fife And Drum sheet music has been read 8548 times. With a fife and drum arrangement is for Advanced level. The music notes has 6 preview and last read at 2021-10-01 00:17:47. [ Read More ] Christmastime Is Here Drum Corps Parade Music Christmastime Is Here Drum Corps Parade Music sheet music has been read 1860 times. Christmastime is here drum corps parade music arrangement is for Advanced level. The music notes has 6 preview and last read at 2021-10-01 12:39:55. [ Read More ] Little Drummer Boy Female Vocal Choir Drum Corps And Pops Orchestra Key Of Eb To F Little Drummer Boy Female Vocal Choir Drum Corps And Pops Orchestra Key Of Eb To F sheet music has been read 3829 times. Little drummer boy female vocal choir drum corps and pops orchestra key of eb to f arrangement is for Advanced level. -

Issue 121 Continues \\~Th Fife .\ Tarry Samp-,On, Wel.T Cojst Editor in Spnill and Drum in Europe, Part 2

PERSONAL • Bus1NESS • TRUST • INVESTMENT SERVICES Offices: Essex, 35 Plains Road. 7o!-2573 • Essex, 9 Main Street, 7o/-&38 Old Saybrook, 15.5 Main Street, 388-3543 • Old Lyme, 101 Halls Road. 434-1646 Member FDIC • Equal Housing Lender www.essexsavings.com 41 EssexFmancialServires Member NA.SD, SIPC Subsidiary of Essex Savings Bank Essex: 176 Westbrook Road (860) 767-4300 • 35 Plains Road (860) 767-2573 Call Toll-Free: 800-900-5972 www.essexfinancialservices.com fNVESTMENTS IN STOCKS. BONDS. MtrT'UAL RJNDS & ANNUITIES: INOT A DEPOSIT INOT FDIC INSURED INOT BANK GUARA,'fl'EED IMAY LOSE VALUE I INOT INSURED BY ANY FEDERAL GOVERNMENT AGENCY I .2 AncientTunes 111t Fifi· rmd Dr11111 l"uc 121 Jul) lXli From the 1 111 Denmark Publt Jied bi Editor The Company of s we're all aware, the 2007 Fifers &Dnmimers 5 muster season is well under http://compan)c1tlifeanddlllm.oii; 111,; Fife n11d tht Dmm A way, fun for all who thrive on Editor: Dan Movbn, Pro Tern in lta(v parades, outdoor music, and fife and Art & ~ign D~ctor. Da,·e Jon~ Advertising Manager: Betty .Moylan drum camaraderie. Please ensure Contributing Editor.Bill .\Wing 7 that there is someone to write up Associate Edi tors: your corps' muster, and that there is Dominkk Cu'-ia, Music Editor Chuck Rik)", Website and Cylx~acc Edimr someone with picrures and captions, .-\m.111dJ Goodheart, Junior XC\1s Editor hoc co submit them co the Ancient ,\I.irk Log.-.don, .\lid,mt Editor Times. Da,c !\ocll, Online Chat Intmicw~ 8 Ed Olsen, .\lo Schoo~. -

USV Fife and Drum Manual Standards, Policies and Regulations

2014 USV Fife and Drum Manual Standards, Policies and Regulations Matthew Marine PRINCIPAL MUSICIAN, 2ND REGIMENT USV, 8TH NJ VOLS. VERSION 1 NOVEMBER 12, 2013 USV FIFE AND DRUM MANUAL 2 USV FIFE AND DRUM MANUAL Contents Introduction ............................................................................................................................................................................................... 4 History .......................................................................................................................................................................................................... 4 Responsibility .............................................................................................................................................................................................. 4 Role ............................................................................................................................................................................................................. 4 Goal ............................................................................................................................................................................................................ 5 Minimum Requirements ........................................................................................................................................................................... 5 Uniforms ..................................................................................................................................................................................................... -

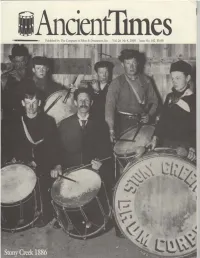

Issue #102, "Corps of Was Voted to Increase the Cover Price of the Ancient 1OK More Words While Ntuntatning a SJZC of the Same -IO Yesterday"

s Your drum head is one of the most powerful influences on your overall performance. \\'e carry a wide selection of synthetic and natural skin heads chosen expressly for rope tension lield drums, providing you with the most extensive range of choices for sound, response, and durabilit_}. We recommend BAffER HEADS these brands and Remo® Fiberskyn 3 (C11.,tM1 Rii11,,) styles ofdrum Remo® Renaissance (Cu.,1<1111 Rim.,) heads. Other Remo~ heads Swiss Kevlar are available Traditional Calfskin upon request as New Professional Calfskin well. - ti1 ,,tack Summer 2{}01 SNARE HEADS Remo® Emperor translucent (Ca.t1,1m Rim.,) Swiss Synthetic Traditional Calfskin New Professional Calfskin - tiz ,,tock Summer 2001 Cooperman File & Drum BASS HEADS Company Remo® Fiberskyn 3 Essex lnduslnal Park, P0. Box 276, 1 1 New Bear ' Kevlar Centerblook, CT 06409-0276 USA Tel: 860-767-1779 - tiz ,,tock tiz 2-1" and 26" diameter,, Fax: 860-767-7017 Traditional Calfskin Email: [email protected] -----~-=--=-=On~llle:::Wro=:~Wil;wcooperman.com Ancienffimes 2 From the 1 No. 1112-No,ombct,:?()II() Tht Corps of Yutmlay Publisher/Editor Publahcd:,; The Company of 14 Fifers cffDrummers w we come to talk ofthe fifes and drums Hanciford's Vol11nturs F&DC ofyesterday. The bcgmmngs of this Editor: Bob l>T.cl· Ctltbratts 25 ¥tars illusmous music are somewhat elusive and Senior Editor: Robin N1mu12 perhaps lost forever in antiqmty. But we Associat• Editon: can n:Oect on the history we have at hand Grrg BJcon, MUll, Editor 15 Nwithin the museum archives. J fascinanng record of fife Jc-1.~ Hili-mon. -

In This Issue: Monumental Memories Le Carillon National, Ah! Ça Ira and the Downfall of Paris, Part 1 Healy Flute Company Skip Healy Fife & Flute Maker

i AncientTimes Published by the Company of fifers & drummers, Inc. fall 2011 Issue 134 $5.00 In thIs Issue: MonuMental MeMorIes le CarIllon natIonal, ah! Ça Ira and the downfall of ParIs, Part 1 HeAly FluTe CompAny Skip Healy Fife & Flute maker Featuring hand-crafted instruments of the finest quality. Also specializing in repairs and restoration of modern and wooden Fifes and Flutes on the web: www.skiphealy.com phone/Fax: (401) 935-9365 email: [email protected] 5 Division Street Box 23 east Greenwich, RI 02818 Afffffordaordable Liability IInsurance Provided by Shoffff Darby Companiies Through membership in the Liivingving Histoory Associatiion $300 can purchaase a $3,000,000 aggregatte/$1,000,000 per occurrennce liability insurance that yyou can use to attend reenactments anywhere, hosted by any organization. Membership dues include these 3 other policies. • $5,010 0 Simple Injuries³Accidental Medical Expense up to $500,000 Aggggregate Limit • $1,010 0,000 organizational liability policy wwhhen hosting an event as LHA members • $5(0 0,000 personal liability policy wwhhen in an offfffiicial capacity hosting an event th June 22³24 The 26 Annual International Time Line Event, the ffiirst walk througghh historryy of its kind establishedd in 1987 on the original site. July 27³29 Ancient Arts Muster hosting everything ffrrom Fife & DDrum Corps, Bag Pipe Bands, craffttspeople, ffoood vendors, a time line of re-enactors, antique vehicles, Native Ameericans, museum exhibits and more. Part of thh the activities during the Annual Blueberry Festival July 27³AAuugust 5 . 9LVLWWKH /+$·VZHEVLWHDW wwwwwww.lliivviinnggghhiissttooryassn.oorg to sign up ffoor our ffrree e-newsletter, event invitations, events schedules, applications and inffoormation on all insurance policies. -

Occasional Bulletins HENRY BURBECK

No. 3 The Papers of Henry Burbeck Clements Library October 2014 OccasionalTHE PAPERS OF HENRY Bulletins BURBECK hen Henry Burbeck fought at the Battle of Bunker Hill Schopieray details, other caches of Burbeck material went to the on June 17, 1775, he had just celebrated his twenty-first Fraunces Tavern Museum in New York, the New London County Wbirthday. The son of a British colonial official who was (Connecticut) Historical Society , the Burton Historical Collection at second in command of Old Castle William in Boston Harbor, young the Detroit Public Library, the United States Military Academy, the Henry could not have foreseen that he would spend the next four New York Public Library, the Newberry Library, and to dealers and decades in ded- collectors. But it icated service to wasn’t until 2011 a new American that the majority nation. In of Burbeck’s those forty manuscripts went years, at half up for sale at a dozen Heritage Auctions Revolutionary in Los Angeles. War battles, at We learned about West Point, at that a day before forts and out- the auction, and posts up and our hurried down the west- run at the papers ern frontier, at fell short. Three the court mar- years later, with tial of James the new Norton Wilkinson, and Strange as Chief of the Townshend Fund In 1790 Henry Burbeck established Fort St. Tammany on the St. Mary’s River, the boundary Artillery Corps providing much- between Georgia and Spanish Florida. He commanded there until 1792. Surgeon’s Mate Nathan from 1802 to needed support Hayward presented Burbeck with this view of the finished fort. -

First Drums 1958 and 1959

THE DRUMS OF THE COLONIAL WILLIAMSBURG FIFES AND DRUMS VISIBLE SYMBOLS OF THE CORPS’ LEGACY BY: BILL CASTERLINE, JANUARY 21, 2012 1 FIRST DRUMS 1958 AND 1959 LEFT: Rehearsal inside the Powder Magazine just prior to the first performance on July 4, 1958, playing drums [1] borrowed from James Blair High School, and close up of one of the drums. MIDDLE LEFT: British Army drums in 1959 photo. The flag carrier on right is William “Bill” Geiger, Director of the Craft Shops and supervisor of the Militia and CWF&D. BELOW LEFT: One of three British Army drums purchased in 1959, with added “VA REGT” painted on the shell. The “worm” design on counter hoops is typical of British drums. One of the original British Army drums will return permanently to the CWF&D in 2012. BELOW RIGHT: 1959 Christmas Guns ceremony on Merchants Square, with Captain Nick Payne in uniform of the Virginia Regiment, during which ceremony original Brown Bess muskets were fired by the Militia. 2 Soistman Drums 1960 LEFT: 1958 visit of the Lancraft Fife and Drum Corps (New Haven, Conn.) provided example of top rate unit and demonstrated viability of a fife and drum corps for Colonial Williamsburg. Lancraft brought its “Grand Republic” drums (close up at left) built by Gus Moeller [2] that provided an example for Colonial Williamsburg of the authenticity and sound produced by such drums that CW was seeking since 1953 [3]. LEFT: July, 1960, training by SP5 George Carroll and Old Guard F&D musicians using a “shield” drum loaned to the Old Guard by Buck Soistman [4] and a Moeller drum from The U.S. -

30 BRANN DAILOR Mastodon Hasn’T Risen to the Top 48 JAMISON ROSS of the Rock Heap by Following the by Jeff Potter Heavy Metal Handbook

BECOME A BETTER DRUMMER, FASTER When you’re serious about drumming, you need a kit to match your ambition. The V-Drums TD-17 series lets your technique shine through, backed up with training tools to push you further. Combining a TD-50-class sound engine with newly developed pads results in an affordable electronic drum kit that’s authentically close to playing acoustic drums – accurately mirroring the physical movement, stick coordination and hand/foot control that every drummer needs. Meanwhile, an array of built-in coaching functions will track your technique, measure your progress and increase your motivation. Becoming a better drummer is still hard work, but the TD-17 can help you get there. TD-17 Series V-Drums www.roland.com BASS HEADS ARE ONE-SIZE-FITS-ALL.* * IF WE BELIEVED THIS, WHY WOULD WE MAKE THREE BRAND NEW CUTTING-EDGE BASS HEADS? This series brings you the same UV-coating that made drummers switch to UV1 tom and snare heads, featuring the UV1 for a wide open sound, the UV EQ4 for balance and sustain, and the UV EMAD for a more focused attack. Because we know not all drummers agree on their bass drum sound. Now you can have your bass and kick it too. FIND YOUR FIT AT UV1.EVANSDRUMHEADS.COM HEAR THE ENTIRE TRUE-SONIC™ SNARE COLLECTION PLAYED BY STANLEY RANDOLPH AT DWDRUMS.COM. WHY SO SENSITIVE? Because all-new Collector’s Series® True-Sonic™ wood snare drums employ a pre-tensioned SnareBridge™ system with a complementary snare bed to provide dry, sensitive articulation. -

Drumtalk Email Hal Leonard to Make Sure Blasts, Our Monthly Storefront Retailers Present Herald Newsletter, These Products Most Effec- Dealer Trade Shows, Tively

5 MAIN REASONS WHY RETAILERS SOURCE TECHNOLOGY & GEAR FROM THE HAL LEONARD MI PRODUCTS DIVISION 1 Great Product Brands It starts with great products. We only distribute popular, proven-best sellers that create faster turns and higher customer satisfaction. Award-Winning Extensive Product Training 2 Customer Service 3 From our knowledgeable sales reps to our exacting Hal Leonard provides volumes of training mate- fulfillment team, our award-winning service gives rials including videos via our YouTube chan- retailers confidence that they are buying the right nel (named “HalLeonardTech”), in-store clinics, products and will get them in a timely, consistent demos at trade shows, and printed materials. manner. Our 24/7 online support and online This helps retail- chat service provides multiple ways ers and their staff for retailers to submit, track and understand what confirm every aspect of their they are buying and order easily. That is why help their custom- Hal Leonard has been ers get the right named MMR Magazine’s product. No other Dealers’ Choice Print gear distributor pro- Music Publisher of the vides this level of Year winner every year support. since 1997. Effective 4 clear communication 5 Merchandising Hal Leonard communicates in multiple ways to Kiosks, displays, posters, ensure retailers know about our products, special and branded point-of-sale services, seasonal specials, and new releases. materials are provided by Via DrumTALK email Hal Leonard to make sure blasts, our monthly storefront retailers present Herald newsletter, these products most effec- dealer trade shows, tively. We also offer a demo school state shows, unit program that allows fliers, phone calls, you to show products out and store visits – of the box.