Review of Angelo Guerraggio and Pietro Nastasi, Italian Mathematics Between the Two World Wars

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Salvatore Pincherle: the Pioneer of the Mellin–Barnes Integrals

Journal of Computational and Applied Mathematics 153 (2003) 331–342 www.elsevier.com/locate/cam Salvatore Pincherle: the pioneer of the Mellin–Barnes integrals Francesco Mainardia;∗, Gianni Pagninib aDipartimento di Fisica, Universita di Bologna and INFN, Sezione di Bologna, Via Irnerio 46, I-40126 Bologna, Italy bIstituto per le Scienze dell’Atmosfera e del Clima del CNR, Via Gobetti 101, I-40129 Bologna, Italy Received 18 October 2001 Abstract The 1888 paper by Salvatore Pincherle (Professor of Mathematics at the University of Bologna) on general- ized hypergeometric functions is revisited. We point out the pioneering contribution of the Italian mathemati- cian towards the Mellin–Barnes integrals based on the duality principle between linear di5erential equations and linear di5erence equation with rational coe7cients. By extending the original arguments used by Pincherle, we also show how to formally derive the linear di5erential equation and the Mellin–Barnes integral representation of the Meijer G functions. c 2002 Elsevier Science B.V. All rights reserved. MSC: 33E30; 33C20; 33C60; 34-XX; 39-XX; 01-99 Keywords: Generalized hypergeometric functions; Linear di5erential equations; Linear di5erence equations; Mellin–Barnes integrals; Meijer G-functions 1. Preface In Vol. 1, p. 49 of Higher Transcendental Functions of the Bateman Project [5] we read “Of all integrals which contain gamma functions in their integrands the most important ones are the so-called Mellin–Barnes integrals. Such integrals were ÿrst introduced by Pincherle, in 1888 [21]; their theory has been developed in 1910 by Mellin (where there are references to earlier work) [17] and they were used for a complete integration of the hypergeometric di5erential equation by Barnes [2]”. -

Science and Fascism

Science and Fascism Scientific Research Under a Totalitarian Regime Michele Benzi Department of Mathematics and Computer Science Emory University Outline 1. Timeline 2. The ascent of Italian mathematics (1860-1920) 3. The Italian Jewish community 4. The other sciences (mostly Physics) 5. Enter Mussolini 6. The Oath 7. The Godfathers of Italian science in the Thirties 8. Day of infamy 9. Fascist rethoric in science: some samples 10. The effect of Nazism on German science 11. The aftermath: amnesty or amnesia? 12. Concluding remarks Timeline • 1861 Italy achieves independence and is unified under the Savoy monarchy. Venice joins the new Kingdom in 1866, Rome in 1870. • 1863 The Politecnico di Milano is founded by a mathe- matician, Francesco Brioschi. • 1871 The capital is moved from Florence to Rome. • 1880s Colonial period begins (Somalia, Eritrea, Lybia and Dodecanese). • 1908 IV International Congress of Mathematicians held in Rome, presided by Vito Volterra. Timeline (cont.) • 1913 Emigration reaches highest point (more than 872,000 leave Italy). About 75% of the Italian popu- lation is illiterate and employed in agriculture. • 1914 Benito Mussolini is expelled from Socialist Party. • 1915 May: Italy enters WWI on the side of the Entente against the Central Powers. More than 650,000 Italian soldiers are killed (1915-1918). Economy is devastated, peace treaty disappointing. • 1921 January: Italian Communist Party founded in Livorno by Antonio Gramsci and other former Socialists. November: National Fascist Party founded in Rome by Mussolini. Strikes and social unrest lead to political in- stability. Timeline (cont.) • 1922 October: March on Rome. Mussolini named Prime Minister by the King. -

The First Period: 1888 - 1904

The first period: 1888 - 1904 The members of the editorial board: 1891: Henri Poincaré entered to belong to “direttivo” of Circolo. (In that way the Rendiconti is the first mathematical journal with an international editorial board: the Acta’s one was only inter scandinavian) 1894: Gösta Mittag-Leffler entered to belong to “direttivo” of Circolo . 1888: New Constitution Art. 2: [Il Circolo] potrà istituire concorsi a premi e farsi promotore di congress scientifici nelle varie città del regno. [Il Circolo] may establish prize competitions and become a promoter of scientific congress in different cities of the kingdom. Art 17: Editorial Board 20 members (five residents and 15 non residents) Art. 18: elections with a system that guarantees the secrety of the vote. 1888: New Editorial Board 5 from Palermo: Giuseppe and Michele Albeggiani; Francesco Caldarera; Michele Gebbia; Giovan Battista Guccia 3 from Pavia: Eugenio Beltrami; Eugenio Bertini; Felice Casorati; 3 from Pisa: Enrico Betti; Riccardo De Paolis; Vito Volterra 2 from Napoli: Giuseppe Battaglini; Pasquale Del Pezzo 2 from Milano: Francesco Brioschi; Giuseppe Jung 2 from Roma: Valentino Cerruti; Luigi Cremona 2 from Torino: Enrico D’Ovidio; Corrado Segre 1 from Bologna: Salvatore Pincherle A very well distributed arrangement of the best Italian mathematicians! The most important absence is that of the university of Padova: Giuseppe Veronese had joined the Circolo in 1888, Gregorio Ricci will never be a member of it Ulisse Dini and Luigi Bianchi in Pisa will join the Circolo respectively in 1900 and in 1893. The first and the second issue of the Rendiconti Some papers by Palermitan scholars and papers by Eugène Charles Catalan, Thomas Archer Hirst, Pieter Hendrik Schoute, Corrado Segre (first issue, 1887) and Enrico Betti, George Henri Halphen, Ernest de Jonquières, Camille Jordan, Giuseppe Peano, Henri Poincaré, Corrado Segre, Alexis Starkov, Vito Volterra (second issue, 1888). -

The Axiomatization of Linear Algebra: 1875-1940

HISTORIA MATHEMATICA 22 (1995), 262-303 The Axiomatization of Linear Algebra: 1875-1940 GREGORY H. MOORE Department of Mathematics, McMaster University, Hamilton, Ontario, Canada L8S 4K1 Modern linear algebra is based on vector spaces, or more generally, on modules. The abstract notion of vector space was first isolated by Peano (1888) in geometry. It was not influential then, nor when Weyl rediscovered it in 1918. Around 1920 it was rediscovered again by three analysts--Banach, Hahn, and Wiener--and an algebraist, Noether. Then the notion developed quickly, but in two distinct areas: functional analysis, emphasizing infinite- dimensional normed vector spaces, and ring theory, emphasizing finitely generated modules which were often not vector spaces. Even before Peano, a more limited notion of vector space over the reals was axiomatized by Darboux (1875). © 1995 AcademicPress, Inc. L'algrbre linraire moderne a pour concept fondamental l'espace vectoriel ou, plus grn6rale- ment, le concept de module. Peano (1888) fut le premier ~ identifier la notion abstraite d'espace vectoriel dans le domaine de la gromrtrie, alors qu'avant lui Darboux avait drj5 axiomatis6 une notion plus 6troite. La notion telle que drfinie par Peano eut d'abord peu de repercussion, mrme quand Weyl la redrcouvrit en 1918. C'est vers 1920 que les travaux d'analyse de Banach, Hahn, et Wiener ainsi que les recherches algrbriques d'Emmy Noether mirent vraiment l'espace vectoriel ~ l'honneur. A partir de 1K la notion se drveloppa rapide- ment, mais dans deux domaines distincts: celui de l'analyse fonctionnelle o,) l'on utilisait surtout les espaces vectoriels de dimension infinie, et celui de la throrie des anneaux oia les plus importants modules etaient ceux qui sont gdnrrrs par un nombre fini d'616ments et qui, pour la plupart, ne sont pas des espaces vectoriels. -

The Role of Salvatore Pincherle in the Development of Fractional Calculus

The Role of Salvatore Pincherle in the Development of Fractional Calculus Francesco Mainardi and Gianni Pagnini Abstract We revisit two contributions by Salvatore Pincherle (Professor of Math- ematics at the University of Bologna from 1880 to 1928) published (in Italian) in 1888 and 1902 in order to point out his possible role in the development of Fractional Calculus. Fractional Calculus is that branch of mathematical analysis dealing with pseudo-differential operators interpreted as integrals and derivatives of non-integer order. Even if the former contribution (published in two notes on Accademia dei Lincei) on generalized hypergeomtric functions does not concern Fractional Calculus it contains the first example in the literature of the use of the so called Mellin–Barnes integrals. These integrals will be proved to be a fundamental task to deal with all higher transcendental functions including the Meijer and Fox functions introduced much later. In particular, the solutions of differential equations of fractional order are suited to be expressed in terms of these integrals. In the second paper (published on Accademia delle Scienze di Bologna), the author is interested to insert in the framework of his operational theory the notion of derivative of non integer order that appeared in those times not yet well established. Unfortunately, Pincherle’s foundation of Fractional Calculus seems still ignored. 1 Some Biographical Notes of Salvatore Pincherle Salvatore Pincherle was born in Trieste on 11 March 1853 and died in Bologna on 10 July 1936. He was Professor of Mathematics at the University of Bologna from 1880 to 1928. Furthermore, he was the founder and the first President of Unione Matematica Italiana (UMI) from 1922 to 1936. -

Bruno De Finetti, Radical Probabilist. International Workshop

Bruno de Finetti, Radical Probabilist. International Workshop Bologna 26-28 ottobre 2006 Some links between Bruno De Finetti and the University of Bologna Fulvia de Finetti – Rome ……… Ladies and Gentleman, let me start thanking the organizing committee and especially Maria Carla Galavotti for the opportunity she has given me to open this International Workshop and talk about my father in front of such a qualified audience. This privilege does not derive from any special merit of my own but from the simple and may I say “casual” fact that my father was Bruno de Finetti. By the way, this reminds me one of the many questions that the little Bruno raised to his mother: “What if you married another daddy and daddy married another mammy? Would I be your son, or daddy’s?” As far as the question concerns myself, my replay is that “I” would not be here to-day! As I did in my speech in Trieste on July 20 2005, for the 20th anniversary of his death, I will try to show the links, between Bruno and Bologna in this case, Trieste last year. Sure, a big difference is the fact that he never lived in Bologna where he spent only few days of his life compared to the twenty and more years he spent in Trieste, yet it was in Bologna in 1928 that he moved the first step in the international academic world. I refer to his participation in the International Congress of Mathematicians held in Bologna in September (3-10) of that year. It was again in Bologna in that same University that he returned fifty-five years later to receive one of the very last tributes to his academic career. -

SOURCES Manuscript Volumes and Lecture Notes of Salvatore Pincherle

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Elsevier - Publisher Connector HISTORIA MATHEMATICA 16 (1989) 379-380 SOURCES This department welcomes correspondence, brief announcements, and article-length de- scriptions of collections of publications, correspondence, and archival material relevant to the history of mathematics. Manuscripts describing major collections (covering such matters as acquisition, size, scope, state of cataloging, and current and future availability) should follow the same standards as other articles. They will be abstracted and indexed like other articles, and authors will be supplied with free reprints. Manuscript Volumes and Lecture Notes of Salvatore Pincherle By Umberto Bottazzini and Stefano Francesconi Dipartimento di Matematica, Universitd degli studi di Bologna, Piazza di Porta S. Donato, 5, 40127 Bologna, Italy AMS 1985 subject classifications: OlA55, OlA60, 46-03. Salvatore Pincherle (Trieste, 1853-Bologna, 1936) was one of the leading Italian mathematicians of his generation. He is remembered for his contributions (e.g., in 1886, 1887, 1896, 1900, and 1901) to the early development of functional analysis. He also founded the UMI (the Italian Mathematical Society) and organized the International Congress of Mathematicians held in Bologna in 1928. Pincherle completed his undergraduate studies in Marseille, France, where Pincherle’s family had gone to live some years after his birth. Between 1869 and 1874 Pincherle was a student at the Scuola Normale Superiore in Pisa. Here he attended classes taught by E. Betti and U. Dini. Three years later, Pincherle went to Berlin, where he studied with K. Weierstrass. After returning to Italy, Pincherle published his well-known Saggio di una introduzione alla teoria delle funzioni anatitiche second0 i principi de1 Prof. -

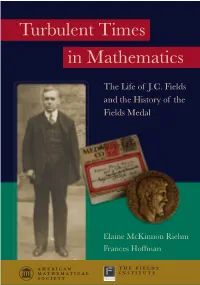

Turbulent Times in Mathematics

Turbulent Times in Mathematics The Life of J.C. Fields and the History of the Fields Medal Elaine McKinnon Riehm Frances Hoffman AMERICAN THE FIELDS MATHEMATICAL INSTITUTE SOCIETY Turbulent Times in Mathematics The Life of J.C. Fields and the History of the Fields Medal AMERICAN MATHEMATICAL SOCIETY THE FIELDS INSTITUTE Original prototype of the Fields Medal, cast in bronze, mailed to J. L. Synge at the University of Toronto in 1933. http://dx.doi.org/10.1090/mbk/080 Turbulent Times in Mathematics The Life of J.C. Fields and the History of the Fields Medal Elaine McKinnon Riehm Frances Hoffman AMERICAN MATHEMATICAL SOCIETY THE FIELDS INSTITUTE 2000 Mathematics Subject Classification. Primary 01–XX, 01A05, 01A55, 01A60, 01A70, 01A73, 01A99, 97–02, 97A30, 97A80, 97A40. Cover photo of J.C. Fields standing outside Convocation Hall — at the time of the IMC, Toronto, 1924 — courtesy of the Thomas Fisher Rare Book Library, University of Toronto. Cover and frontispiece photo of the Fields Medal and its original box courtesy of Andrea Yeomans. For additional information and updates on this book, visit www.ams.org/bookpages/mbk-80 Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Riehm, Elaine McKinnon, 1936– Turbulent times in mathematics : the life of J. C. Fields and the history of the Fields Medal / Elaine McKinnon Riehm, Frances Hoffman. p. cm. Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 978-0-8218-6914-7 (alk. paper) 1. Fields, John Charles, 1863–1932. 2. Mathematicians—Canada—Biography. 3. Fields Prizes. I. Hoffman, Frances, 1944– II. Title. QA29.F54 R53 2011 510.92—dc23 [B] 2011021684 Copying and reprinting. -

Salvatore Pincherle the Pioneer of the Mellin-Barnes Integrals

FRACALMO PRE-PRINT www.fracalmo.org Journal of Computational and Applied Mathematics Vol. 153 (2003), pp. 331-342 Salvatore Pincherle the pioneer of the Mellin-Barnes integrals Francesco MAINARDI(1), Gianni PAGNINI(2) (1) Department of Physics, University of Bologna, and INFN, Via Irnerio 46, I-40126 Bologna, Italy Corresponding Author; E-mail: [email protected] (2)ENEA: Italian Agency for New Technologies, Energy and the Environment Via Martiri di Monte Sole 4, I-40129 Bologna, Italy E-mail: [email protected] Abstract The 1888 paper by Salvatore Pincherle (Professor of Mathematics at the Uni- versity of Bologna) on generalized hypergeometric functions is revisited. We point out the pioneering contribution of the Italian mathematician towards the Mellin-Barnes integrals based on the duality principle between linear dif- ferential equations and linear difference equation with rational coefficients. By extending the original arguments used by Pincherle, we also show how to formally derive the linear differential equation and the Mellin-Barnes integral representation of the Meijer G functions. Keywords: Generalized hypergeometric functions, linear differential equa- tions, linear difference equations, Mellin-Barnes integrals, Meijer G-functions. MSC: 33E30, 33C20, 33C60, 34-XX, 39-XX, 01-99. arXiv:math/0702520v1 [math.CV] 18 Feb 2007 1. Preface In Vol. 1, p. 49 of Higher Transcendental Functions of the Bateman Project [5] we read ”Of all integrals which contain gamma functions in their inte- grands the most important ones are the so-called Mellin-Barnes integrals. Such integrals were first introduced by S. Pincherle, in 1888 [21]; their the- ory has been developed in 1910 by H. -

Table of Contents

Contents Foreword, by Ivor Grattan-Guinness ..................................... v Preface ............................................................. vii Illustrations .......................................................... xv History and Geography .............................................. xvii 1 Life and Works................................................... 1 1.1 Biography...................................................... 4 1.1.1 Lucca................................................... 4 1.1.2 Bologna: Studies..........................................7 1.1.3 Pisa ................................................... 10 1.1.4 Turin.................................................. 17 1.1.5 The Bologna Affair....................................... 25 1.1.6 Catania ................................................ 32 1.1.7 Parma ................................................. 44 1.1.8 Afterward .............................................. 47 1.2 Overview of Pieri’s Research...................................... 50 1.2.1 Algebraic and Differential Geometry, Vector Analysis . ......... 50 1.2.2 Foundations of Geometry.................................. 54 1.2.3 Arithmetic, Logic, and Philosophy of Science.................. 58 1.2.4 Conclusion.............................................. 61 1.3 Others........................................................ 62 2 Foundations of Geometry .......................................... 123 2.1 Historical Context ............................................. 125 2.2 Hypothetical-Deductive -

Placido Tardy E La Sua Corrispondenza Con Luigi Cremona: Un Progetto Di Ricerca

"The geography of the Rendiconti del Circolo Matematico di Palermo: local and international aspects " Cinzia Cerroni Università di Palermo Giovan Battista Guccia (Palermo 1855 – 1914) Some reference dates 1884: The foundation of “Circolo Matematico di Palermo” 1886-88: The “Circolo” has developed as national society of the mathematicians. 1887: Released the first volume of “Rendiconti del Circolo Matematico di Palermo”. 1888: New Constitution and New Editorial Board 1891: Henri Poincarè entered to belong to “direttivo” of Circolo. 1894: Gösta Mittag-Leffler entered to belong to “direttivo” of Circolo. The main periods Three main periods: 1888 – 1904: the Circolo as a national association; 1904 – 1908: the strategy of Guccia for the internationalization of the Circolo; 1908 – 1914: the great growth. Members of Circolo Matematico of Palermo 1884 Not residents in Palermo, 5, 19% Residents in Palermo, 22, 81% Total 27 Residents in Palermo 22 Not residents in Palermo 5 1886/1887: The first not – palermitan members of the Circolo 1886: Eugene Catalan; Giuseppe Battaglini; Valentino Cerruti; Pasquale Del Pezzo 1887: Thomas Archer Hirst; Ernesto Cesaro; Corrado Segre; Francesco Brioschi; Luigi Cremona; Enrico D’Ovidio; Luigi Berzolari; Georges Humbert; Gino Loria; Giuseppe Peano; Vito Volterra; Enrico Betti The first period: 1888 - 1904 The members of the editorial board: 1891: Henri Poincaré entered to belong to “direttivo” of Circolo. (In that way the Rendiconti is the first mathematical journal with an international editorial board: the Acta’s one was only inter scandinavian) 1894: Gösta Mittag-Leffler entered to belong to “direttivo” of Circolo. 1888: New Constitution Art. 2: [Il Circolo] potrà istituire concorsi a premi e farsi promotore di congress scientifici nelle varie città del regno. -

On Some Historical Aspects of Riemann Zeta Function, 3 Giuseppe Iurato

On some historical aspects of Riemann zeta function, 3 Giuseppe Iurato To cite this version: Giuseppe Iurato. On some historical aspects of Riemann zeta function, 3. 2014. hal-00974034 HAL Id: hal-00974034 https://hal.archives-ouvertes.fr/hal-00974034 Preprint submitted on 4 Apr 2014 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. On some historical aspects of Riemann zeta function, 3 Giuseppe Iurato University of Palermo, IT [email protected] Abstract In this third note, we deepen, from either an historical and histori- ographical standpoint, the arguments treated in the previous preprint hal.archives-ouvertes.fr/hal-00907136 - version 1. Roughly, the history of entire function theory starts with the theorems of factorization of a certain class of complex functions, later called entire transcen- dental functions by Weierstrass (see (Loria 1950, Chapter XLIV, Section 741) and (Klein 1979, Chapter VI)), which made their explicit appearance around the mid-1800s, within the wider realm of complex function theory which had its paroxysmal moment just in the 19th century. But, if one wished to identify, with a more precision, that chapter of complex function theory which was the crucible of such a theory, then the history would lead to elliptic function theory and related factorization theorems for doubly periodic elliptic functions, these latter being meant as a generalization of trigonometric functions.