19 the Hero in Contemporary Spanish American

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

How One Education Leader's Newark Nonprofit Became One of the Few

DeVos Takes Tough Stance as Storytime, Livestreamed: Congressional Democrats How One Texas Principal Is Hammer Her on Budget Using Facebook to Read Her Cuts, School Choice Students — and Thousands of Fans Around the World — Bedtime Stories Every News The 74 Interview How One Education Leader’s Newark Nonprofit Became One of the Few Minority-Led Groups to Win a $30 Million Federal Grant to Fight Poverty February 11, 2019 By MIMI WOLDEYOHANNES Updated Feb. 12 Mimi Woldeyohannes is a special projects & community manager at The See previous 74 interviews: Sen. Cory Booker talks 74 about the success of Newark’s school reforms, civil rights activist Dr. Howard Fuller talks equity in education, Harvard professor Karen Mapp talks [email protected] family engagement, former U.S. Department of Education secretary John King talks the Trump TALKING POINTS administration, and more. The full archive is right here. Founder and CEO of @BrickAcademy Dominique Lee talks ominique Lee made headlines as a 25- about winning $30M D year-old when he and four other fed grant, “breaking Teach for America alumni took over a failing down walls and Newark elementary school and turned it into building up kids” in #Newark’s South BRICK Avon Academy, the acronym standing Ward. for Building Responsible Intelligent Creative Kids. As was widely reported, a fustrated South Ward Lee decided to launch his own school with Children’s Alliance fellow teachers afer seeing ninth-graders at plans to use $30M @usedgov grant to the city’s Malcolm X. Shabazz High School expand health care, unable to name the seven continents or the housing, early state’s governor. -

Ophelia Lived on the Floating Ark of Anima, One of the Few Territories To

THE MIRROR VISITOR 2. T HE MISSING OF CLAIRDELUNE VOLUME 1 R ECALLED A W INTER ’S PROMISE phelia lived on the floating ark of Anima, one of the few territories to survive the Rupture of the old O world. And before she was betrothed, all was for the best in the best of all possible shattered worlds. Ophelia was certainly one of the clumsiest Animists, due to an accident with a mirror, but her hands had always produced excellent read - ings of objects and she felt at home in her museum. So, the day Thorn tears her away from her family and her ark to take her to the Pole, it’s her own world that’s shattered. Ophelia discov - ers the Citaceleste, a floating city built on illusions. The nobles there are endowed with dangerous powers and ready for all kinds of treachery to gain the favor of Farouk, their family spirit. He is the half-human, half-divine figure who rules over the Pole, and a disturbing character, to say the least. It doesn’t help that Thorn is the son of a disgraced woman and Treasurer of the Pole, so he’s detested by everyone. With the collusion of his aunt, Berenilde, he hides his fiancée from everyone while awaiting the marriage. First locked away in a manor, then disguised as a valet, Ophelia gets to know the ins and outs of this world that rejects her before even knowing her. And that’s how she finally learns of the existence of Farouk’s Book, an ancient and enigmatic tome with which the family spirit is truly obsessed. -

The ICD-10 Classification of Mental and Behavioural Disorders

The ICD-10 Classification of Mental and Behavioural Disorders Clinical descriptions and diagnostic guidelines World Health Organization -1- Preface In the early 1960s, the Mental Health Programme of the World Health Organization (WHO) became actively engaged in a programme aiming to improve the diagnosis and classification of mental disorders. At that time, WHO convened a series of meetings to review knowledge, actively involving representatives of different disciplines, various schools of thought in psychiatry, and all parts of the world in the programme. It stimulated and conducted research on criteria for classification and for reliability of diagnosis, and produced and promulgated procedures for joint rating of videotaped interviews and other useful research methods. Numerous proposals to improve the classification of mental disorders resulted from the extensive consultation process, and these were used in drafting the Eighth Revision of the International Classification of Diseases (ICD-8). A glossary defining each category of mental disorder in ICD-8 was also developed. The programme activities also resulted in the establishment of a network of individuals and centres who continued to work on issues related to the improvement of psychiatric classification (1, 2). The 1970s saw further growth of interest in improving psychiatric classification worldwide. Expansion of international contacts, the undertaking of several international collaborative studies, and the availability of new treatments all contributed to this trend. Several national psychiatric bodies encouraged the development of specific criteria for classification in order to improve diagnostic reliability. In particular, the American Psychiatric Association developed and promulgated its Third Revision of the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual, which incorporated operational criteria into its classification system. -

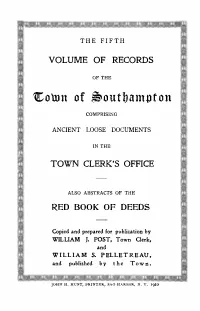

1Town of Outbamtlton

THE FIFTH VOLUME OF RECORDS OF THE 1town of �outbamtlton COMPRISING ANCIENT LOOSE DOCUMENTS IN THE TOWN CLERK'S OFFICE ALSO ABSTRACTS OF THE RED BOOK OF DEEDS Copied and prepared for publication by WILLIAM J. POST, Town Clerk, and WILLIAM S. PELLETRE AU, and published b V th e Tow n • JOHN H. HUNT, PRINTER, SAG HARBOR, N. Y. 1910 LIBRARY OF THE TOWN OF SOUTHAMPTON Ofice of the Historian This bok may be examined and studied in the Historian's Office or elsewhere in the Town Hall but it must not be taken from the building. HIstorian I The mission of the Historic Division of the Town Clerk's Office IS to preserve and protect the Town of Southampton's historic holdings for generations to come. The few copies that we have of our original editions of the Record Books of the Town of Southampton are now in need of preservation. In addition to preserving our Town's record books, our goal is to provide improved access to those people that are interested in exploring the wonderful history of the Town of Southampton. Technological developments have allowed us to scan the originals in order to reprint each volume and also to post them on our website offering new search capabilities that have not been available in the past. Respectfully yours, Sundy A. Schermeyer, Town Clerk CERTIFICATION State of New York ) ss.: County of Suffolk) Officeof the Town Clerk Southampton, New York This is to certify that I, Sundy A. Schet'meyer, Clerk of the Town of Southampton, in the said County of Suffolk, State of New York, have compared the original Fifth Book of Records of the Town of Southampton, Long Island, N. -

Track List: All Songs Written by Syd Barrett, Except Where Noted. ”UK Release” Side One 1

Track List: All songs written by Syd Barrett, except where noted. ”UK release” Side one 1. "Astronomy Domine" – 4:12 2. "Lucifer Sam" – 3:07 3. "Matilda Mother" – 3:08 4. "Flaming" – 2:46 5. "Pow R. Toc H." (Syd Barrett, Roger Waters, Rick Wright, Nick Mason) – 4:26 6. "Take Up Thy Stethoscope and Walk" (Roger Waters) – 3:05 Side two 1. "Interstellar Overdrive" (Syd Barrett, Roger Waters, Rick Wright, Nick Mason) – 9:41 2. "The Gnome" – 2:13 The Piper at the Gates of Dawn – August 5, 1967 3. "Chapter 24" – 3:42 Syd Barrett – guitar, lead vocals, back cover design 4. "The Scarecrow" – 2:11 5. "Bike" – 3:21 Roger Waters – bass guitar, vocals Rick Wright – Farfisa Compact Duo, Hammond organ, Certifications: piano, vocals TBR Nick Mason – drums, percussion "Astronomy Domine" Lime and limpid green, a second scene A fight between the blue you once knew. Floating down, the sound resounds Around the icy waters underground. Jupiter and Saturn, Oberon, Miranda and Titania. Neptune, Titan, Stars can frighten. Lime and limpid green, a second scene A fight between the blue you once knew. Floating down, the sound resounds Around the icy waters underground. Jupiter and Saturn, Oberon, Miranda and Titania. Neptune, Titan, Stars can frighten. Blinding signs flap, Flicker, flicker, flicker blam. Pow, pow. Stairway scare, Dan Dare, who's there? Lime and limpid green, the sounds around The icy waters under Lime and limpid green, the sounds around The icy waters underground. "Lucifer Sam" Lucifer Sam, siam cat. Always sitting by your side Always by your side. -

Politics of the Past: the Use and Abuse of History

Cover History and Politics:Mise en page 1 3/20/09 4:04 PM Page 1 Twenty years after the end of the Cold War and the collapse of communism the battles about the right interpretation of the twentieth century past are still being fought. In some countries even the courts have their say on what is or is not the historical truth. But primarily politicians have claimed a dominant role Politics of the Past: in these debates, often mixing history and politics in an irresponsible way. The European Parliament has become the arena where this culminates. Nevertheless, not every Member of Parliament wants to play historian. That is the The Use and Abuse of History background of Politics of the Past, in which historians take the floor to discuss the tense and ambivalent relationship between their profession and politics. Pierre Hassner: “Judges are no better placed than governments to replace open Edited by dialogue between historians, between historians and public opinion, between citizens and within and between democratic societies. That is why this book is Hannes Swoboda and such an important initiative.” Jan Marinus Wiersma Politics of the Past: The Use and Abuse of History The of the Past: Politics Cover picture: Reporters/AP 5 7 2 6 2 3 2 8 2 9 ISBN 92-823-2627-5 8 7 QA-80-09-552-EN-C ISBN 978-92-823-2627-5 9 Politics of the Past: The Use and Abuse of History Edited by Hannes Swoboda and Jan Marinus Wiersma Dedicated to Bronisław Geremek Bronisław Geremek, historian, former political dissident and our dear colleague, was one of the speakers at the event which we organized in Prague to commemorate the Spring of 1968. -

Thomas Dolby Mad Scientists, Hip-Hop Hits, the Wall and the Nokia Signature Tone

Thomas Dolby Mad scientists, hip-hop hits, The Wall and the Nokia signature tone. Once described as steampunk’s Iggy Pop, this boffin-like new waver is certainly out there with his paeans to eco warriors and the golden CUNEIFORM RECORDS CUNEIFORM age of radio. But now we ask the big question: how prog is Thomas Dolby? Words: Paul Lester remember seeing She Blinded Me prototype. “Eno performed similar With Science, the song Thomas Aliens Ate My feats but he never compromised his Dolby did with Magnus Pyke instrumental work, which has been – who in the early 80s was the Buick made so influential over the years.” definitive TV ‘mad scientist’ me realise Like Eno – and Gabriel and, for that “Iwhite-haired boffin – on telly when matter, Todd Rundgren – Dolby is I was about 10,” recalls Steve Jefferis that taking yourself virtually synonymous with eclecticism of Warm Digits, those north-eastern and electronic experimentation, with purveyors of kosmische electronica too seriously gadgetry and whizkiddery. and technoid prog. “It was like the is ridiculous. “Peter Gabriel is one of the few Open University had suddenly opened people in the world I would happily a portal onto the stage of Top Of The Simon Godfrey change places with,” he admits. “He’s Pops, and now seems like a great a wonderful writer and singer. He’s example of the plain weirdness that Dolby, Brian Eno was going to move always been single-minded, making passed for mainstream pop when in at one point. Prog ventures that his albums under his own steam despite we were kids. -

Songs of the Sioux AFS

Recording Laboratory AFS L23 Songs of the Sioux From the Archive of Folk Song Recorded and Edited by Frances Densmore Library of Congress Washington 1951 Library ofCongress Catalog Card Number R55-353 rev A vailable from the Library ofCongress Music Division, Recorded Sound Section Washington, D.C. 20540 SONGS OF THE SIOUX PREFACE Music, Pawnee Music, Yuman and Yaqui Music, Chey enne and Arapaho Music, Choctaw Music, Music of The records of Indian songs, edited by Frances Dens the Indians ofBritish Columbia, Nootka and Quileute more, make available to students and scholars the Music, Music of the Tule Indians of Panama, and a hitherto inaccessible and extraordinarily valuable number of volumes on related subjects. Now, as a original recordings of Indian music which now form a fitting complement to these publications, Dr. Dens part of the collections of the Archive of Folk Song in more selected from the thousands of cylinders the the Library of Congress. The original recordings were most representative and most valid-in terms of the made with portable cylinder equipment in the field sound quality of the original recordings-songs of the over a period of many years as part of Dr. Densmore's different Indian tribes. With the recordings, she also research for the Bureau of American Ethnology of prepared accompanying texts and notes-such as the Smithsonian Institution. The recordings were sub those contained in this pamphlet-which authenti sequently transferred to the National Archives and cally explain the background and tribal use of the Record Service and, finally, to the Library of Con music for the interested student. -

Paranoia and Determinism Versus Anti-Paranoia and Non-Determinism in Thomas Pynchon's Gravity's Rainbow Liane Rausch Petersen Iowa State University

Iowa State University Capstones, Theses and Retrospective Theses and Dissertations Dissertations 1979 Paranoia and determinism versus anti-paranoia and non-determinism in Thomas Pynchon's Gravity's Rainbow Liane Rausch Petersen Iowa State University Follow this and additional works at: https://lib.dr.iastate.edu/rtd Part of the English Language and Literature Commons Recommended Citation Petersen, Liane Rausch, "Paranoia and determinism versus anti-paranoia and non-determinism in Thomas Pynchon's Gravity's Rainbow" (1979). Retrospective Theses and Dissertations. 14357. https://lib.dr.iastate.edu/rtd/14357 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Iowa State University Capstones, Theses and Dissertations at Iowa State University Digital Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Retrospective Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Iowa State University Digital Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Paranoia and determinism versus anti-paranoia and non-determinism in Thomas Pynchon's Gravity's Rainbow by Liane Rausch Petersen A Thesis Submitted to the Graduate Faculty in Partial Fulfillment of The Requirements for the Degree of MASTER OF ARTS Major: English Signatures have been redacted for privacy Iowa State University Ames, Iowa 1979 11 TABLE OF CONTENTS Page PARANOIA AND DETERMINISM VERSUS ANTI-PARANOIA AND NON-DETERMINISM IN THOMAS PYNCHON'S GRAVITY'S RAINBOW 1 NOTES 26 BIBLIOGRAPHY OF WORKS CITED 27 SUPPLEMENTAL BIBLIOGRAPHY 28 1 PARANOIA AND DETERMINISM VERSUS ANTI-PARANOIA AND NON-DETERMINISM IN THOMAS PYNCHON'S GRAVITY'S RAINBOW Paranoia and anti-paranoia are central concepts in Thomas Pynchon's Gravity's Rainbow, yet only one extended study of the conflicting concepts has been written. -

A Comparative Analysis of Humanity's Core Themes in the Music of Bob

University of Nebraska - Lincoln DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln Honors Theses, University of Nebraska-Lincoln Honors Program Spring 4-16-2018 From Rain’s A-gonna Fall to Bricks in the Wall: A Comparative Analysis of Humanity’s Core Themes in the Music of Bob Dylan and Pink Floyd Alec Williams University of Nebraska-Lincoln Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/honorstheses Part of the Musicology Commons, and the Other Music Commons Williams, Alec, "From Rain’s A-gonna Fall to Bricks in the Wall: A Comparative Analysis of Humanity’s Core Themes in the Music of Bob Dylan and Pink Floyd" (2018). Honors Theses, University of Nebraska-Lincoln. 25. https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/honorstheses/25 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Honors Program at DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. It has been accepted for inclusion in Honors Theses, University of Nebraska-Lincoln by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. From rain’s a-gonna fall to bricks in the wall: A comparative analysis of humanity’s core themes in the music of Bob Dylan and Pink Floyd An Undergraduate Honors Thesis Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of University Honors Program Requirements University of Nebraska-Lincoln By Alec Williams, BS Biological Sciences and Economics College of Arts and Sciences 15 April 2018 Faculty Mentor: Dr. Scott Anderson, D. M. A. Glenn Korff School of Music 1 Abstract The 1960s were turbulent times of musical creation and revolution. From Motown to Dinkytown, the world suddenly became filled with blooms of creativity that stemmed from the freshly planted roots rock ‘n’ roll. -

On Writing : a Memoir of the Craft / by Stephen King

l l SCRIBNER 1230 Avenue of the Americas New York, NY 10020 Visit us on the World Wide Web http://www.SimonSays.com Copyright © 2000 by Stephen King All rights reserved, including the right of reproduction in whole or in part in any form. SCRIBNER and design are trademarks of Macmillan Library Reference USA, Inc., used under license by Simon & Schuster, the publisher of this work. DESIGNED BY ERICH HOBBING Set in Garamond No. 3 Library of Congress Publication data is available King, Stephen, 1947– On writing : a memoir of the craft / by Stephen King. p. cm. 1. King, Stephen, 1947– 2. Authors, American—20th century—Biography. 3. King, Stephen, 1947—Authorship. 4. Horror tales—Authorship. 5. Authorship. I. Title. PS3561.I483 Z475 2000 813'.54—dc21 00-030105 [B] ISBN 0-7432-1153-7 Author’s Note Unless otherwise attributed, all prose examples, both good and evil, were composed by the author. Permissions There Is a Mountain words and music by Donovan Leitch. Copyright © 1967 by Donovan (Music) Ltd. Administered by Peer International Corporation. Copyright renewed. International copyright secured. Used by permission. All rights reserved. Granpa Was a Carpenter by John Prine © Walden Music, Inc. (ASCAP). All rights administered by WB Music Corp. All rights reserved. Used by permission. Warner Bros. Publications U.S. Inc., Miami, FL 33014. Honesty’s the best policy. —Miguel de Cervantes Liars prosper. —Anonymous First Foreword In the early nineties (it might have been 1992, but it’s hard to remember when you’re having a good time) I joined a rock- and-roll band composed mostly of writers. -

The Hunger Games Chapter One 0.Pdf

SUZANNE COLLINS 221587_00_i-vi_r8ga.indd1587_00_i-vi_r8ga.indd iiiiii 44/29/08/29/08 33:53:54:53:54 PMPM 1 When I wake up, the other side of the bed is cold. My fingers stretch out, seeking Prim’s warmth but finding only the rough canvas cover of the mattress. She must have had bad dreams and climbed in with our mother. Of course, she did. This is the day of the reaping. I prop myself up on one elbow. There’s enough light in the bedroom to see them. My little sister, Prim, curled up on her side, cocooned in my mother’s body, their cheeks pressed together. In sleep, my mother looks younger, still worn but not so beaten-down. Prim’s face is as fresh as a raindrop, as lovely as the primrose for which she was named. My mother was very beautiful once, too. Or so they tell me. Sitting at Prim’s knees, guarding her, is the world’s ugli- est cat. Mashed-in nose, half of one ear missing, eyes the color of rotting squash. Prim named him Buttercup, insist- ing that his muddy yellow coat matched the bright flower. He hates me. Or at least distrusts me. Even though it was years ago, I think he still remembers how I tried to drown him in a bucket when Prim brought him home. Scrawny kitten, belly swollen with worms, crawling with fleas. The last thing I needed was another mouth to feed. But Prim begged so hard, cried even, I had to let him stay.