A Comparative Study on the Relationship Between Spiral Forms in Sufi Spiral Dance (Sama) and Persian Islamic Paintings

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A Sufi Reading of Jesus

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by The University of Sydney: Sydney eScholarship Journals... Representations of Jesus in Islamic Mysticism: Defining the „Sufi Jesus‟ Milad Milani Created from the wine of love, Only love remains when I die. (Rumi)1 I‟ve seen a world without a trace of death, All atoms here have Jesus‟ pure breath. (Rumi)2 Introduction This article examines the limits touched by one religious tradition (Islam) in its particular approach to an important symbolic structure within another religious tradition (Christianity), examining how such a relationship on the peripheries of both these faiths can be better apprehended. At the heart of this discourse is the thematic of love. Indeed, the Qur’an and other Islamic materials do not readily yield an explicit reference to love in the way that such a notion is found within Christianity and the figure of Jesus. This is not to say that „love‟ is altogether absent from Islamic religion, since every Qur‟anic chapter, except for the ninth (surat at-tawbah), is prefaced In the Name of God; the Merciful, the Most Kind (bismillahi r-rahmani r-rahim). Love (Arabic habb; Persian Ishq), however, becomes a foremost concern of Muslim mystics, who from the ninth century onward adopted the theme to convey their experience of longing for God. Sufi references to the theme of love starts with Rabia al-Adawiyya (717-801) and expand outward from there in a powerful tradition. Although not always synonymous with the figure of Jesus, this tradition does, in due course, find a distinct compatibility with him. -

Cholland Masters Thesis Final Draft

Copyright By Christopher Paul Holland 2010 The Thesis committee for Christopher Paul Holland Certifies that this is the approved version of the following thesis: Rethinking Qawwali: Perspectives of Sufism, Music, and Devotion in North India APPROVED BY SUPERVISING COMMITTEE: Supervisor: __________________________________ Syed Akbar Hyder ___________________________________ Gail Minault Rethinking Qawwali: Perspectives of Sufism, Music, and Devotion in North India by Christopher Paul Holland B.A. Thesis Presented to the Faculty of the Graduate School of the University of Texas at Austin in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts The University of Texas at Austin May 2010 Rethinking Qawwali: Perspectives of Sufism, Music, and Devotion in North India by Christopher Paul Holland, M.A. The University of Texas at Austin, 2010 SUPERVISOR: Syed Akbar Hyder Scholarship has tended to focus exclusively on connections of Qawwali, a north Indian devotional practice and musical genre, to religious practice. A focus on the religious degree of the occasion inadequately represents the participant’s active experience and has hindered the discussion of Qawwali in modern practice. Through the examples of Nusrat Fateh Ali Khan’s music and an insightful BBC radio article on gender inequality this thesis explores the fluid musical exchanges of information with other styles of Qawwali performances, and the unchanging nature of an oral tradition that maintains sociopolitical hierarchies and gender relations in Sufi shrine culture. Perceptions of history within shrine culture blend together with social and theological developments, long-standing interactions with society outside of the shrine environment, and an exclusion of the female body in rituals. -

Understanding the Concept of Islamic Sufism

Journal of Education & Social Policy Vol. 1 No. 1; June 2014 Understanding the Concept of Islamic Sufism Shahida Bilqies Research Scholar, Shah-i-Hamadan Institute of Islamic Studies University of Kashmir, Srinagar-190006 Jammu and Kashmir, India. Sufism, being the marrow of the bone or the inner dimension of the Islamic revelation, is the means par excellence whereby Tawhid is achieved. All Muslims believe in Unity as expressed in the most Universal sense possible by the Shahadah, la ilaha ill’Allah. The Sufi has realized the mysteries of Tawhid, who knows what this assertion means. It is only he who sees God everywhere.1 Sufism can also be explained from the perspective of the three basic religious attitudes mentioned in the Qur’an. These are the attitudes of Islam, Iman and Ihsan.There is a Hadith of the Prophet (saw) which describes the three attitudes separately as components of Din (religion), while several other traditions in the Kitab-ul-Iman of Sahih Bukhari discuss Islam and Iman as distinct attitudes varying in religious significance. These are also mentioned as having various degrees of intensity and varieties in themselves. The attitude of Islam, which has given its name to the Islamic religion, means Submission to the Will of Allah. This is the minimum qualification for being a Muslim. Technically, it implies an acceptance, even if only formal, of the teachings contained in the Qur’an and the Traditions of the Prophet (saw). Iman is a more advanced stage in the field of religion than Islam. It designates a further penetration into the heart of religion and a firm faith in its teachings. -

Iran 2019 International Religious Freedom Report

IRAN 2019 INTERNATIONAL RELIGIOUS FREEDOM REPORT Executive Summary The constitution defines the country as an Islamic republic and specifies Twelver Ja’afari Shia Islam as the official state religion. It states all laws and regulations must be based on “Islamic criteria” and an official interpretation of sharia. The constitution states citizens shall enjoy human, political, economic, and other rights, “in conformity with Islamic criteria.” The penal code specifies the death sentence for proselytizing and attempts by non-Muslims to convert Muslims, as well as for moharebeh (“enmity against God”) and sabb al-nabi (“insulting the Prophet”). According to the penal code, the application of the death penalty varies depending on the religion of both the perpetrator and the victim. The law prohibits Muslim citizens from changing or renouncing their religious beliefs. The constitution also stipulates five non-Ja’afari Islamic schools shall be “accorded full respect” and official status in matters of religious education and certain personal affairs. The constitution states Zoroastrians, Jews, and Christians, excluding converts from Islam, are the only recognized religious minorities permitted to worship and form religious societies “within the limits of the law.” The government continued to execute individuals on charges of “enmity against God,” including two Sunni Ahwazi Arab minority prisoners at Fajr Prison on August 4. Human rights nongovernmental organizations (NGOs) continued to report the disproportionately large number of executions of Sunni prisoners, particularly Kurds, Baluchis, and Arabs. Human rights groups raised concerns regarding the use of torture, beatings in custody, forced confessions, poor prison conditions, and denials of access to legal counsel. -

Islamic Esotericism in the Bengali Bāul Songs of Lālan Fakir Keith Cantú [email protected]

Research Article Correspondences 7, no. 1 (2019): 109–165 Special Issue: Islamic Esotericism Islamic Esotericism in the Bengali Bāul Songs of Lālan Fakir Keith Cantú [email protected] Abstract This article makes use of the author’s field research as well as primary and secondary textual sour- ces to examine Islamic esoteric content, as mediated by local forms of Bengali Sufism, in Bāul Fa- kiri songs. I provide a general summary of Bāul Fakiri poets, including their relationship to Islam as well as their departure from Islamic orthodoxy, and present critical annotated translations of five songs attributed to the nineteenth-century Bengali poet Lālan Fakir (popularly known as “Lalon”). I also examine the relationship of Bāul Fakiri sexual rites (sādhanā) and principles of embodiment (dehatattva), framed in Islamic terminology, to extant scholarship on Haṭhayoga and Tantra. In the final part of the article I emphasize how the content of these songs demonstrates the importance of esotericism as a salient category in a Bāul Fakiri context and offer an argument for its explanatory power outside of domains that are perceived to be exclusively Western. Keywords: Sufism; Islam; Esotericism; Metaphysics; Traditionalism The history of the Bāul Fakirs includes centuries of religious innovation in which various poets have gradually created a folk tradition highly unique to Bengal, that is, Bangladesh and West Bengal, India. While there have been several important works published on Bāul Fakirs in recent years,1 in this ar- ticle I aim to contribute specifically to scholarship on Islamic esoteric con- tent in Bāul Fakiri songs, as mediated by local forms of Sufism.2 Analyses in 1. -

The Barzakh of Flamenco: Tracing the Spirituality, Locality and Musicality of Flamenco from South of the Strait of Gibraltar

SIT Graduate Institute/SIT Study Abroad SIT Digital Collections Independent Study Project (ISP) Collection SIT Study Abroad Fall 2011 The aB rzakh of Flamenco: Tracing the Spirituality, Locality and Musicality of Flamenco From South of the Strait of Gibraltar Tania Flores SIT Study Abroad Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcollections.sit.edu/isp_collection Part of the Dance Commons, Ethnomusicology Commons, and the Other Languages, Societies, and Cultures Commons Recommended Citation Flores, Tania, "The aB rzakh of Flamenco: Tracing the Spirituality, Locality and Musicality of Flamenco From South of the Strait of Gibraltar" (2011). Independent Study Project (ISP) Collection. 1118. https://digitalcollections.sit.edu/isp_collection/1118 This Unpublished Paper is brought to you for free and open access by the SIT Study Abroad at SIT Digital Collections. It has been accepted for inclusion in Independent Study Project (ISP) Collection by an authorized administrator of SIT Digital Collections. For more information, please contact [email protected]. The Barzakh of Flamenco: Tracing the Spirituality, Locality and Musicality of Flamenco from South of the Strait of Gibraltar Tania Flores Occidental College Migration and Transnational Identity: Fall 2011 Flores 2 Acknowledgments I could not have completed this project without the advice and guidance of my academic director, Professor Souad Eddouada; my advisor, Professor Taieb Belghazi; my professor of music at Occidental College, Professor Simeon Pillich; my professor of Islamic studies at Occidental, Professor Malek Moazzam-Doulat; or my gracious and helpful interviewees. I am also grateful to Elvira Roca Rey for allowing me to use her studio to choreograph after we had finished dance class, and to Professor Said Graiouid for his guidance and time. -

Consumer Culture in Saudi Arabia

Consumer Culture in Saudi Arabia: A Qualitative Study among Heads of Household. Submitted by Theeb Mohammed Al Dossry to the University of Exeter as a Thesis for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Sociology September 2012 This thesis is available for Library use on the understanding that it is copyright material and that no quotation from the thesis may be published without proper acknowledgement. I certify that all material in this thesis which is not my own work has been identified and that no material has previously been submitted and approved for the award of a degree by this or any other University. Signature: ……………………………………… 1 Dedication I dedicate this thesis to my family especially: My father who taught me, how ambitious I should be, he is my inspiration for everything. My mother who surrounded me with her love, praying for me throughout the time I spent working on my thesis. To all my brother and sisters (Noura, Hoda, Nasser, Dr Mounera, Abdullah and Abdurrahman). With a special dedication to my lovely wife (Nawal) and my sons (Mohammed and Feras) 2 Abstract As Saudi Arabia turns towards modernisation, it faces many tensions and conflicts during that process. Consumerism is an extremely controversial subject in Saudi society. The purpose of this study was to investigate the changes that the opportunities and constraints of consumerism have brought about in the specific socio-economic and cultural settings between local traditions, religion, familial networks and institutions, on the one hand, and the global flow of money, goods, services and information, on the other. A qualitative method was applied. -

Sufism: in the Spirit of Eastern Spiritual Traditions

92 Sufism: In the Spirit of Eastern Spiritual Traditions Irfan Engineer Volume 2 : Issue 1 & Volume Center for the Study of Society & Secularism, Mumbai [email protected] Sambhāṣaṇ 93 Introduction Sufi Islam is a mystical form of Islamic spirituality. The emphasis of Sufism is less on external rituals and more on the inward journey. The seeker searches within to make oneself Insaan-e-Kamil, or a perfect human being on God’s path. The origin of the word Sufism is in tasawwuf, the path followed by Sufis to reach God. Some believe it comes from the word suf (wool), referring to the coarse woollen fabric worn by early Sufis. Sufiya also means purified or chosen as a friend of God. Most Sufis favour the origin of the word from safa or purity; therefore, a Sufi is one who is purified from worldly defilements. The essence of Sufism, as of most religions, is to reach God, or truth or absolute reality. Characteristics of Sufism The path of Sufism is a path of self-annihilation in God, also called afanaa , which means to seek permanence in God. A Sufi strives to relinquish worldly and even other worldly aims. The objective of Sufism is to acquire knowledge of God and achieve wisdom. Sufis avail every act of God as an opportunity to “see” God. The Volume 2 : Issue 1 & Volume Sufi “lives his life as a continuous effort to view or “see” Him with a profound, spiritual “seeing” . and with a profound awareness of being continuously overseen by Him” (Gulen, 2006, p. xi-xii). -

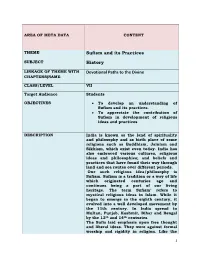

Sufism and Its Practices History Devotional Paths to the Divine

AREA OF META DATA CONTENT THEME Sufism and its Practices SUBJECT History LINKAGE OF THEME WITH Devotional Paths to the Divine CHAPTERS(NAME CLASS/LEVEL VII Target Audience Students OBJECTIVES To develop an understanding of Sufism and its practices. To appreciate the contribution of Sufism in development of religious ideas and practices DESCRIPTION India is known as the land of spirituality and philosophy and as birth place of some religions such as Buddhism, Jainism and Sikhism, which exist even today. India has also embraced various cultures, religious ideas and philosophies; and beliefs and practices that have found their way through land and sea routes over different periods. One such religious idea/philosophy is Sufism. Sufism is a tradition or a way of life which originated centuries ago and continues being a part of our living heritage. The term Sufism’ refers to mystical religious ideas in Islam. While it began to emerge in the eighth century, it evolved into a well developed movement by the 11th century. In India spread to Multan, Punjab, Kashmir, Bihar and Bengal by the 13th and 14th centuries. The Sufis laid emphasis upon free thought and liberal ideas. They were against formal worship and rigidity in religion. Like the 1 Bhakti saints, the Sufis too interpreted religion as ‘love of god’ and service of humanity. Sufis believe that there is only one God and that all people are the children of God. They also believe that to love one’s fellow men is to love God and that different religions are different ways to reach God. -

Dervish on the Eurovision Stage Popular Music and the Heterogeneity of Power Interests in Contemporary Turkey

Dervish on the Eurovision Stage Popular Music and the Heterogeneity of Power Interests in Contemporary Turkey Nevin Şahin Turkey’s journey of the Eurovision Song Contest (ESC), dominated by national- istic identity claims, started in 1975, culminated in the country’s victory in 2003, and abruptly came to an end in 2012 in Baku. Turkey’s four decades of ESC participation illuminated conflicting power interests from the selection process of the songs to the decision process of the stage performances. The debates peaked in the 2004 final ESC night in İstanbul regarding the representation of whirling dervishes. Different stakeholders, including the tourist industry, the national broadcast channel Türkiye Radyo ve Televizyon Kurumu (TRT), the Ministry of Culture and Tourism, Sufi circles, and the singer and winner of the 2003 ESC Sertab Erener, influenced the participation of whirling dervishes in the 2004 round of the ESC. In doing so, they created a web of contesting power dynamics, which can be theorized in the context of public diplomacy. Historian Jessica Gienow-Hecht emphasizes the heterogeneity in the struc- ture of agency in cultural diplomacy (10). In a parallel manner, this chapter argues that there are heterogeneous power interests of different agents in the context of popular music and diplomacy in Turkey. How does the performance of “Turkishness,” emblematized by whirling dervishes on the ESC stage, reflect the competition and collaboration of actors in the cultural domain? In an effort to highlight power dynamics behind Turkey’s ESC performance, this chapter first focuses on Turkey’s ESC history. It then moves towards the competitive staging of whirling dervishes in other public events, followed by a Bourdieusian analysis of power and music diplomacy. -

Inter Faith Week 2011 Event List

List of events ‐ Inter Faith Week 2011 ID 2 Date of Event: 25 November 2011 IFN Member?: No Name of Event: Shared Values GCSE Ethics Conference Organisation(s) holding the event: South Bromsgrove High School Short description of event: RE staff and 6th form students ran an Ethics Conference on the theme of 'Shared Values' to promote community cohesion. GCSE RE students from Worcestershire schools shared inter faith dialogue with faith representatives. Name of venue: South Bromsgrove High School Venue town Worcester Venue type School ID 5 Date of Event: 20 November 2011 IFN Member?: No Name of Event: Multifaith Celebration of Inter Faith Week 2011 Organisation(s) holding the event: Guildford and Godalming Inter‐Faith Forum Short description of event: Attended by representatives of local faith groups including Bahá'í, Buddhist, Christian, Hindu, Muslim and Sikh faiths and local Mayors of Guildford and Godalming. Name of venue: St Nicholas Parish Room Venue town Guildford Venue type Church hall ID 6 Date of Event: 25 November 2011 IFN Member?: No Name of Event: Living Library: Don't judge a book by its cover! Organisation(s) holding the event: Faith Encounter Programme Short description of event: People of different faiths were available as ’living books’ for conversation and to break down stereotypes and prejudices. Schools were invited to bring student groups to take part. Two venues, one city centre church and one suburban library. Name of venue: Carrs Lane Church Centre Venue town Birmingham Venue type URC Church Centre ID 7 Date of Event: 26 November 2011 IFN Member?: No Name of Event: Living Library: Don't judge a book by its cover! Organisation(s) holding the event: Faith Encounter Programme Short description of event: People of different faiths were available as ’living books’ for conversation to break down stereotypes and prejudices. -

HC Dissertation Final

Distribution Agreement In presenting this thesis or dissertation as a partial fulfillment of the requirements for an advanced degree from Emory University, I hereby grant to Emory University and its agents the non-exclusive license to archive, make accessible, and display my thesis or dissertation in whole or in part in all forms of media, now or hereafter known, including display on the world wide web. I understand that I may select some access restrictions as part of the online submission of this thesis or dissertation. I retain all ownership rights to the copyright of the thesis or dissertation. I also retain the right to use in future works (such as articles or books) all or part of this thesis or dissertation. Signature: _____________________________ ________________ Date A Muslim Humanist of the Ottoman Empire: Ismail Hakki Bursevi and His Doctrine of the Perfect Man By Hamilton Cook Doctor of Philosophy Islamic Civilizations Studies _________________________________________ Professor Vincent J. Cornell Advisor _________________________________________ Professor Ruby Lal Committee Member _________________________________________ Professor Devin J. Stewart Committee Member Accepted: _________________________________________ Lisa A. Tedesco, Ph.D. Dean of the James T. Laney School of Graduate Studies ___________________ Date A Muslim Humanist of the Ottoman Empire: Ismail Hakki Bursevi and His Doctrine of the Perfect Man By Hamilton Cook M.A. Brandeis University, 2013 B.A., Brandeis University, 2012 Advisor: Vincent J. Cornell, Ph.D.