The Museumification of Rumi's Tomb

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

1 | Mysticism Mysticism: a False Model of the Christian's Communion with God and Sanctification by Pastor Mark R. Perkins H

Mysticism: A False Model of the Christian's Communion with God and Sanctification By Pastor Mark R. Perkins Human spirituality has suffered more from the assault of mysticism than from any other enemy. Even among Christians, mysticism is overwhelmingly misunderstood, rampantly practiced against every caution, and is a vital conduit for the introduction of a great volume of false doctrine into the world. Today, mysticism is wildly popular among Christians. Movements such as contemplative spirituality, spiritual formation, and in large part the charismatic branch of evangelical Christianity all have significant elements of mysticism. Because of extensive involvement in mysticism, the result to Christianity through the ages has been nothing less than devastating. In generation after generation mysticism has produced heresy and war, and from association with the name of Christ has done significant harm to the reputation of Christians and the church. The purpose of this presentation is to define mysticism, and then to determine whether the biblical description of communion with God, and of sanctification, meets that definition. Other benefits will accrue in the journey. The Definition of Mysticism According to the concise Oxford English Dictionary, a mystic is “a person who seeks by contemplation and self–surrender to attain unity with the Deity or the absolute, and so reach truths beyond human understanding.”1 While anything mystical is something “having a spiritual, symbolic, or allegorical significance that transcends human understanding… relating to ancient religious mysteries or other occult rites.”2 The Oxford Dictionary of the Christian Church adds this illumination, “In modern usage ‘mysticism’ generally refers to claims of immediate knowledge of Ultimate Reality whether or not this is called ‘God’) by direct personal experience;”3 Finally, Francis Schaeffer emphasizes the unintelligibility of mysticism, “Mysticism is nothing more than a faith contrary to rationality, deprived of content and incapable of communication. -

Prayer of Supplication Almighty God, Your Son Jesus Christ Was Lifted High Upon the Cross So He Might Draw the Whole World to Himself

UMC of Cucamonga “Tenebrae Service” Prayer of Supplication Almighty God, your Son Jesus Christ was lifted high upon the cross so he might draw the whole world to himself. Grant that we, who glory in his death for our salvation, may also glory in his call to take up our cross and follow him; through Jesus Christ our lord. Amen. Message : Lamb of God It’s dark outside this evening. It’s appropriate for us to gather at this time for a service of Tenebrae, a service of darkness, when we remember Jesus’ death on a cross. But there’s a big difference: the darkness we are experiencing is natural. The sun has set and the stars and moon are out. The darkness that covered the land of Israel on the Friday afternoon when Jesus was crucified was different. Supernatural darkness covered the whole land. Jesus was crucified at mid-day and died in the middle of the afternoon, so the sun was out – yet it could not be seen. Passover is always held during a time of the new moon – there is no way it could have been an eclipse. The darkness represented all the forces of evil and the darkness of our sins as they gathered at one moment. I believe it would be truly frightening to experience, regardless of our modern scientific knowledge and sophistication. That’s because the darkness was palpable and true evil was present. If we had been there, we would have wondered, “What’s up?” What happened that afternoon was foretold. It fulfilled God’s Law. -

The Book of Common Prayer

The Book of Common Prayer and Administration of the Sacraments and Other Rites and Ceremonies of the Church Together with The Psalter or Psalms of David According to the use of The Episcopal Church Church Publishing Incorporated, New York Certificate I certify that this edition of The Book of Common Prayer has been compared with a certified copy of the Standard Book, as the Canon directs, and that it conforms thereto. Gregory Michael Howe Custodian of the Standard Book of Common Prayer January, 2007 Table of Contents The Ratification of the Book of Common Prayer 8 The Preface 9 Concerning the Service of the Church 13 The Calendar of the Church Year 15 The Daily Office Daily Morning Prayer: Rite One 37 Daily Evening Prayer: Rite One 61 Daily Morning Prayer: Rite Two 75 Noonday Prayer 103 Order of Worship for the Evening 108 Daily Evening Prayer: Rite Two 115 Compline 127 Daily Devotions for Individuals and Families 137 Table of Suggested Canticles 144 The Great Litany 148 The Collects: Traditional Seasons of the Year 159 Holy Days 185 Common of Saints 195 Various Occasions 199 The Collects: Contemporary Seasons of the Year 211 Holy Days 237 Common of Saints 246 Various Occasions 251 Proper Liturgies for Special Days Ash Wednesday 264 Palm Sunday 270 Maundy Thursday 274 Good Friday 276 Holy Saturday 283 The Great Vigil of Easter 285 Holy Baptism 299 The Holy Eucharist An Exhortation 316 A Penitential Order: Rite One 319 The Holy Eucharist: Rite One 323 A Penitential Order: Rite Two 351 The Holy Eucharist: Rite Two 355 Prayers of the People -

Point Cloud Registration and Virtual Realization of Large Scale and More Complex Historical Structures

International Archives of the Photogrammetry, Remote Sensing and Spatial Information Sciences, Volume XL-7/W2, 2013 ISPRS2013-SSG, 11 – 17 November 2013, Antalya, Turkey POINT CLOUD REGISTRATION AND VIRTUAL REALIZATION OF LARGE SCALE AND MORE COMPLEX HISTORICAL STRUCTURES C. Altuntas*, F. Yildiz Selcuk University, Engineering Faculty, Department of Geomatics, 42075, Selcuklu, Konya, Turkey - [email protected] Commission V KEY WORDS: Terrestrial, Laser Scanning, Point Cloud, Registration, Accuracy, Three-Dimensional, Cultural Heritage ABSTRACT: Digital information technology always needs more information about object and its relations. Thus, three-dimensional (3D) models of historical structures are created for visualize and documentation of them. Laser scanner performs collecting spatial data with fast and high density. 3D modeling is extensively performed by terrestrial laser scanner (TLS) with high accuracy. At the same time, point cloud registration of large scale objects must be performed precisely for high accuracy 3D modeling. In this study, 3D model was created by measuring the historical Mevlana Museum in Konya with terrestrial laser scanner. Outside and inside point clouds were registered relation one of the point clouds selected from the measurements. In addition accuracy evaluation was performed for created point cloud model. In addition, important details were specifically imaged by mapping photographs onto the point cloud and detail measurements were given. 1. INTRODUCTION Sultanul-Ulema Bahaeddin Veled who is the father of Mevlana. Sultanul-Ulema was buried in the present mausoleum after his The historical structures have to be documented with all the death. The mausoleum where the Green Dome (Kubbe-i Hadra) details in order to maintain and restore to their original forms is located was built with the permission of the son of Mevlana, and re-build when they are destroyed. -

The 21 Century New Muslim Generation Converts in Britain And

The 21st Century New Muslim Generation Converts in Britain and Germany Submitted by Caroline Neumueller to the University of Exeter as a thesis for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Arab and Islamic Studies October 2012 1 2 Abstract The dissertation focuses on the conversion experiences and individual processes of twenty-four native British Muslim converts and fifty-two native German Muslim converts, based on personal interviews and completed questionnaires between 2008 and 2010. It analyses the occurring similarities and differences among British and German Muslim converts, and puts them into relation to basic Islamic requirements of the individual, and in the context of their respective social settings. Accordingly, the primary focus is placed on the changing behavioural norms in the individual process of religious conversion concerning family and mixed-gender relations and the converts’ attitudes towards particularly often sensitive and controversial topics. My empirical research on this phenomenon was guided by many research questions, such as: What has provoked the participants to convert to Islam, and what impact and influence does their conversion have on their (former and primarily) non-Muslim environment? Do Muslim converts tend to distance themselves from their former lifestyles and change their social behavioural patterns, and are the objectives and purposes that they see themselves having in the given society directed to them being: bridge-builders or isolators? The topic of conversion to Islam, particularly within Western non-Muslim societies is a growing research phenomenon. At the same time, there has only been little contribution to the literature that deals with comparative analyses of Muslim converts in different countries. -

P30-31S Layout 1

Established 1961 31 Wednesday, December 20, 2017 Lifestyle Feature Turkey’s dervishes whirl for Rumi anniversary ‘A lot of people like his poetry because it comes from the heart, from his soul’ Whirling dervishes perform a “Sema” ritual during a ceremony. rms crossed over their hearts, hands rest- fit and their tall cap-one hand pointed towards ing on their shoulders, the dervishes start the sky and another towards the earth-has Atheir dance. They turn on themselves, become one of the most famous symbols of slowly sliding their hands along their bodies Turkey. The audience watched entranced at a before raising them, embracing the universe. But dance which copies the movement of planets far from being only an act of introvert worship, against a background of Sufi music that filled the dance of the whirling dervishes is now a the large Konya Sports and Congress Centre. huge spectacle in Turkey, attracting flocks of “A lot of people like his poetry because it tourists every year. Every December, the comes from the heart, from his soul. And in his Turkish city of Konya organizes 10 days of cele- soul, he was with Allah,” said Andrey Zhuravlyov brations to commemorate the death on who came from Latvia for the third time. At December 17, 1273, of Jalal ud-Din Muhammad Rumi’s mausoleum-recognizable by its Rumi, the Sufi mystic who is one of the world’s turquoise-tiled dome-tourists jostle each other, most beloved poets. reflect deeply and some weep profusely at the It was Rumi’s followers who founded the tomb of the poet. -

Contestations, Conflicts and Music-Power: Mevlevi Sufism in the 21St Century Turkey

CONTESTATIONS, CONFLICTS AND MUSIC-POWER: MEVLEVI SUFISM IN THE 21ST CENTURY TURKEY A THESIS SUBMITTED TO THE GRADUATE SCHOOL OF SOCIAL SCIENCES OF MIDDLE EAST TECHNICAL UNIVERSITY BY NEVİN ŞAHİN IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY IN THE DEPARTMENT OF SOCIOLOGY FEBRUARY 2016 Approval of the Graduate School of Social Sciences _____________________________ Prof. Dr. Meliha Altunışık Director I certify that this thesis satisfies all the requirements as a thesis for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy. _____________________________ Prof. Dr. Sibel Kalaycıoğlu Head of Department This is to certify that we have read this thesis and that in our opinion it is fully adequate, in scope and quality, as a thesis for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy. _____________________________ Assoc. Prof. Dr. Mustafa Şen Supervisor Examining Committee Members Assoc. Prof. Dr. Zana Çıtak (METU, IR) _____________________________ Assoc. Prof. Dr. Mustafa Şen (METU, SOC) _____________________________ Assoc. Prof. Dr. Cenk Güray (YBU, MUS) _____________________________ Assist. Prof. Dr. Yelda Özen (YBU, SOC) _____________________________ Assist. Prof. Dr. Çağatay Topal (METU, SOC) _____________________________ I hereby declare that all information in this document has been obtained and presented in accordance with academic rules and ethical conduct. I also declare that, as required by these rules and conduct, I have fully cited and referenced all material and results that are not original to this work. Name, Last name: Nevin Şahin Signature: iii ABSTRACT CONTESTATIONS, CONFLICTS AND MUSIC-POWER: MEVLEVI SUFISM IN THE 21ST CENTURY TURKEY Şahin, Nevin PhD. Department of Sociology Supervisor: Assoc. Prof. Dr. Mustafa Şen February 2016, 232 pages Established as a Sufi order in central Anatolia following the death of Rumi, Mevlevi Sufism has influenced the spirituality of people for over 8 centuries. -

Sufism and Music: from Rumi (D.1273) to Hazrat Inayat Khan (D.1927) Grade Level and Subject Areas Overview of the Lesson Learni

Sufism and Music: From Rumi (d.1273) to Hazrat Inayat Khan (d.1927) Grade Level and Subject Areas Grades 7 to 12 Social Studies, English, Music Key Words: Sufism, Rumi, Hazrat Inayat Khan Overview of the lesson A mystic Muslim poet who wrote in Persian is one of American’s favorite poets. His name is Mevlana Jalaluddin Rumi (1207-1273), better known a Rumi. How did this happen? The mystical dimension of Islam as developed by Sufism is often a neglected aspect of Islam’s history and the art forms it generated. Rumi’s followers established the Mevlevi Sufi order in Konya, in what is today Turkey. Their sema, or worship ceremony, included both music and movement (the so-called whirling dervishes.) The Indian musician and Sufi Hazrat Inayat Khan (1882-1927) helped to introduce European and American audiences to Sufism and Rumi’s work in the early decades of the twentieth century. This lesson has three activities. Each activity is designed to enhance an appreciation of Sufism as reflected in Rumi’s poetry. However, each may also be implemented independently of the others. Learning Outcomes: The student will be able to: • Define the characteristics of Sufism, using Arabic terminology. • Analyze the role music played in the life of Inayat Khan and how he used it as a vehicle to teach about Sufism to American and European audiences. • Interpret the poetry of Rumi with reference to the role of music. Materials Needed • The handouts provided with this lesson: Handout 1; The Emergence of Sufism in Islam (featured in the Handout 2: The Life and Music of Inayat Khan Handout 3: Music in the Poems of Rumi Author: Joan Brodsky Schur. -

Sufism: in the Spirit of Eastern Spiritual Traditions

92 Sufism: In the Spirit of Eastern Spiritual Traditions Irfan Engineer Volume 2 : Issue 1 & Volume Center for the Study of Society & Secularism, Mumbai [email protected] Sambhāṣaṇ 93 Introduction Sufi Islam is a mystical form of Islamic spirituality. The emphasis of Sufism is less on external rituals and more on the inward journey. The seeker searches within to make oneself Insaan-e-Kamil, or a perfect human being on God’s path. The origin of the word Sufism is in tasawwuf, the path followed by Sufis to reach God. Some believe it comes from the word suf (wool), referring to the coarse woollen fabric worn by early Sufis. Sufiya also means purified or chosen as a friend of God. Most Sufis favour the origin of the word from safa or purity; therefore, a Sufi is one who is purified from worldly defilements. The essence of Sufism, as of most religions, is to reach God, or truth or absolute reality. Characteristics of Sufism The path of Sufism is a path of self-annihilation in God, also called afanaa , which means to seek permanence in God. A Sufi strives to relinquish worldly and even other worldly aims. The objective of Sufism is to acquire knowledge of God and achieve wisdom. Sufis avail every act of God as an opportunity to “see” God. The Volume 2 : Issue 1 & Volume Sufi “lives his life as a continuous effort to view or “see” Him with a profound, spiritual “seeing” . and with a profound awareness of being continuously overseen by Him” (Gulen, 2006, p. xi-xii). -

Sufism and Its Practices History Devotional Paths to the Divine

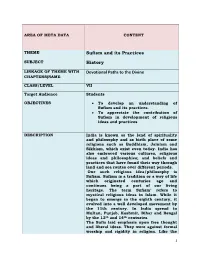

AREA OF META DATA CONTENT THEME Sufism and its Practices SUBJECT History LINKAGE OF THEME WITH Devotional Paths to the Divine CHAPTERS(NAME CLASS/LEVEL VII Target Audience Students OBJECTIVES To develop an understanding of Sufism and its practices. To appreciate the contribution of Sufism in development of religious ideas and practices DESCRIPTION India is known as the land of spirituality and philosophy and as birth place of some religions such as Buddhism, Jainism and Sikhism, which exist even today. India has also embraced various cultures, religious ideas and philosophies; and beliefs and practices that have found their way through land and sea routes over different periods. One such religious idea/philosophy is Sufism. Sufism is a tradition or a way of life which originated centuries ago and continues being a part of our living heritage. The term Sufism’ refers to mystical religious ideas in Islam. While it began to emerge in the eighth century, it evolved into a well developed movement by the 11th century. In India spread to Multan, Punjab, Kashmir, Bihar and Bengal by the 13th and 14th centuries. The Sufis laid emphasis upon free thought and liberal ideas. They were against formal worship and rigidity in religion. Like the 1 Bhakti saints, the Sufis too interpreted religion as ‘love of god’ and service of humanity. Sufis believe that there is only one God and that all people are the children of God. They also believe that to love one’s fellow men is to love God and that different religions are different ways to reach God. -

Between Heterodox and Sunni Orthodox Islam: the Bektaşi Order in the Nineteenth Century and Its Opponents

turkish historical review 8 (2017) 203-218 brill.com/thr Between Heterodox and Sunni Orthodox Islam: The Bektaşi Order in the Nineteenth Century and Its Opponents Butrus Abu-Manneh University of Haifa, Israel [email protected] Abstract In the first quarter of the nineteenth century Ottoman society, especially in cities suffered from a dichotomy. On the one hand there existed for several centuries the Bektaşi which was heterodox order. But in the eighteenth century there started to ex- pand from India a new sufi order: the Naqshbandi – Mujaddidi order known to have been a shari’a minded and highly orthodox order. The result was a dichotomy between religious trends the clash between which reached a high level in 1826. Following the destruction of the janissaries, the Bektaşi order lost its traditional protector and few weeks later was abolished. But a generation later it started to experience a beginning of a revival and by the mid 1860s it started to practice unhindered. But after the rise of Sultan Abdülhamid ii (in 1876) the Bektaşis were again forced to practice clandes- tinely. However, they supported Mustafa Kemal in the national struggle. Keywords The Bektaşi order – Naqshbandi-Mujaddidi – Ali Paşa – Fuad Paşa – Sultan Abdulhamid ii – Bektaşi revival Throughout its long history the Bektaşi order contributed considerably to the Ottoman empire which was, as is known, a multi-national and multi- denominational state. It remained unchallenged by other orders for over three centuries. However, it started to encounter a socio-religious hostility of a newly expanded order which reached the Ottoman lands from India at about the end of the seventeenth and the early eighteenth centuries, as we shall see hereafter. -

A Project Model in Interior Architecture: from Patterns to Spaces

Global Journal of Arts Education Volume 07, Issue 2, (2017) 40-46 www.gjae.eu A project model in interior architecture: From patterns to spaces Rabia Kose Dogan*, Department of Interior Architecture and Environmental Design, Faculty of Fine Arts, Seljuk University, 42079, Konya, Turkey. Suggested Citation: Dogan, K.R. (2017). A project model in interior architecture: From patterns to spaces. Global Journal of Arts Education. 7(2), 40-46 Received December 21, 2016; revised March 26, 2016; accepted May 23, 2016. Selection and peer review under responsibility of Prof. Dr. Ayse Cakir Ilhan, Ankara University, Turkey. ©2017 SciencePark Research, Organization & Counseling. All rights reserved. Abstract Dating back to 3000 BC, Alaaddin Hill is located right in the heart of Konya province, which used to be the capital of Seljuk Civilization. More than 60 years wedding halls built on Alaaddin Hill is hardly ever used due to the reason that cars are unable to reach this area because there is an ongoing landscaping for almost four years. This building has become a problem for the city, also getting older every year. In this aspect, this building is revised as Museum of Seljuk Civilizations and projects are prepared to re-function it within the scope of course name Interior Architecture Project-7 by Seljuk University, Faculty of Fine Arts, Department of Interior Architecture and Environmental Design during fall semester of 2015-2016 education year. There are 48 students in this project. Technical visits are made to the building, field studies are concluded and research is conducted. The underlying reason of this project work is the Seljuk patterns.