DENVER AIRPORT: Operating Results and Financial Risks GAO

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

My Personal Callsign List This List Was Not Designed for Publication However Due to Several Requests I Have Decided to Make It Downloadable

- www.egxwinfogroup.co.uk - The EGXWinfo Group of Twitter Accounts - @EGXWinfoGroup on Twitter - My Personal Callsign List This list was not designed for publication however due to several requests I have decided to make it downloadable. It is a mixture of listed callsigns and logged callsigns so some have numbers after the callsign as they were heard. Use CTL+F in Adobe Reader to search for your callsign Callsign ICAO/PRI IATA Unit Type Based Country Type ABG AAB W9 Abelag Aviation Belgium Civil ARMYAIR AAC Army Air Corps United Kingdom Civil AgustaWestland Lynx AH.9A/AW159 Wildcat ARMYAIR 200# AAC 2Regt | AAC AH.1 AAC Middle Wallop United Kingdom Military ARMYAIR 300# AAC 3Regt | AAC AgustaWestland AH-64 Apache AH.1 RAF Wattisham United Kingdom Military ARMYAIR 400# AAC 4Regt | AAC AgustaWestland AH-64 Apache AH.1 RAF Wattisham United Kingdom Military ARMYAIR 500# AAC 5Regt AAC/RAF Britten-Norman Islander/Defender JHCFS Aldergrove United Kingdom Military ARMYAIR 600# AAC 657Sqn | JSFAW | AAC Various RAF Odiham United Kingdom Military Ambassador AAD Mann Air Ltd United Kingdom Civil AIGLE AZUR AAF ZI Aigle Azur France Civil ATLANTIC AAG KI Air Atlantique United Kingdom Civil ATLANTIC AAG Atlantic Flight Training United Kingdom Civil ALOHA AAH KH Aloha Air Cargo United States Civil BOREALIS AAI Air Aurora United States Civil ALFA SUDAN AAJ Alfa Airlines Sudan Civil ALASKA ISLAND AAK Alaska Island Air United States Civil AMERICAN AAL AA American Airlines United States Civil AM CORP AAM Aviation Management Corporation United States Civil -

Airport Size and Urban Growth

A Service of Leibniz-Informationszentrum econstor Wirtschaft Leibniz Information Centre Make Your Publications Visible. zbw for Economics Sheard, Nicholas Conference Paper Airport size and urban growth 55th Congress of the European Regional Science Association: "World Renaissance: Changing roles for people and places", 25-28 August 2015, Lisbon, Portugal Provided in Cooperation with: European Regional Science Association (ERSA) Suggested Citation: Sheard, Nicholas (2015) : Airport size and urban growth, 55th Congress of the European Regional Science Association: "World Renaissance: Changing roles for people and places", 25-28 August 2015, Lisbon, Portugal, European Regional Science Association (ERSA), Louvain-la-Neuve This Version is available at: http://hdl.handle.net/10419/124561 Standard-Nutzungsbedingungen: Terms of use: Die Dokumente auf EconStor dürfen zu eigenen wissenschaftlichen Documents in EconStor may be saved and copied for your Zwecken und zum Privatgebrauch gespeichert und kopiert werden. personal and scholarly purposes. Sie dürfen die Dokumente nicht für öffentliche oder kommerzielle You are not to copy documents for public or commercial Zwecke vervielfältigen, öffentlich ausstellen, öffentlich zugänglich purposes, to exhibit the documents publicly, to make them machen, vertreiben oder anderweitig nutzen. publicly available on the internet, or to distribute or otherwise use the documents in public. Sofern die Verfasser die Dokumente unter Open-Content-Lizenzen (insbesondere CC-Lizenzen) zur Verfügung gestellt haben sollten, If the documents have been made available under an Open gelten abweichend von diesen Nutzungsbedingungen die in der dort Content Licence (especially Creative Commons Licences), you genannten Lizenz gewährten Nutzungsrechte. may exercise further usage rights as specified in the indicated licence. www.econstor.eu Airport Size and Urban Growth* Nicholas Sheard† September 2015 Abstract This paper estimates the effects of airports on economic growth in US metropolitan areas. -

Airlines Codes

Airlines codes Sorted by Airlines Sorted by Code Airline Code Airline Code Aces VX Deutsche Bahn AG 2A Action Airlines XQ Aerocondor Trans Aereos 2B Acvilla Air WZ Denim Air 2D ADA Air ZY Ireland Airways 2E Adria Airways JP Frontier Flying Service 2F Aea International Pte 7X Debonair Airways 2G AER Lingus Limited EI European Airlines 2H Aero Asia International E4 Air Burkina 2J Aero California JR Kitty Hawk Airlines Inc 2K Aero Continente N6 Karlog Air 2L Aero Costa Rica Acori ML Moldavian Airlines 2M Aero Lineas Sosa P4 Haiti Aviation 2N Aero Lloyd Flugreisen YP Air Philippines Corp 2P Aero Service 5R Millenium Air Corp 2Q Aero Services Executive W4 Island Express 2S Aero Zambia Z9 Canada Three Thousand 2T Aerocaribe QA Western Pacific Air 2U Aerocondor Trans Aereos 2B Amtrak 2V Aeroejecutivo SA de CV SX Pacific Midland Airlines 2W Aeroflot Russian SU Helenair Corporation Ltd 2Y Aeroleasing SA FP Changan Airlines 2Z Aeroline Gmbh 7E Mafira Air 3A Aerolineas Argentinas AR Avior 3B Aerolineas Dominicanas YU Corporate Express Airline 3C Aerolineas Internacional N2 Palair Macedonian Air 3D Aerolineas Paraguayas A8 Northwestern Air Lease 3E Aerolineas Santo Domingo EX Air Inuit Ltd 3H Aeromar Airlines VW Air Alliance 3J Aeromexico AM Tatonduk Flying Service 3K Aeromexpress QO Gulfstream International 3M Aeronautica de Cancun RE Air Urga 3N Aeroperlas WL Georgian Airlines 3P Aeroperu PL China Yunnan Airlines 3Q Aeropostal Alas VH Avia Air Nv 3R Aerorepublica P5 Shuswap Air 3S Aerosanta Airlines UJ Turan Air Airline Company 3T Aeroservicios -

Fields Listed in Part I. Group (8)

Chile Group (1) All fields listed in part I. Group (2) 28. Recognized Medical Specializations (including, but not limited to: Anesthesiology, AUdiology, Cardiography, Cardiology, Dermatology, Embryology, Epidemiology, Forensic Medicine, Gastroenterology, Hematology, Immunology, Internal Medicine, Neurological Surgery, Obstetrics and Gynecology, Oncology, Ophthalmology, Orthopedic Surgery, Otolaryngology, Pathology, Pediatrics, Pharmacology and Pharmaceutics, Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation, Physiology, Plastic Surgery, Preventive Medicine, Proctology, Psychiatry and Neurology, Radiology, Speech Pathology, Sports Medicine, Surgery, Thoracic Surgery, Toxicology, Urology and Virology) 2C. Veterinary Medicine 2D. Emergency Medicine 2E. Nuclear Medicine 2F. Geriatrics 2G. Nursing (including, but not limited to registered nurses, practical nurses, physician's receptionists and medical records clerks) 21. Dentistry 2M. Medical Cybernetics 2N. All Therapies, Prosthetics and Healing (except Medicine, Osteopathy or Osteopathic Medicine, Nursing, Dentistry, Chiropractic and Optometry) 20. Medical Statistics and Documentation 2P. Cancer Research 20. Medical Photography 2R. Environmental Health Group (3) All fields listed in part I. Group (4) All fields listed in part I. Group (5) All fields listed in part I. Group (6) 6A. Sociology (except Economics and including Criminology) 68. Psychology (including, but not limited to Child Psychology, Psychometrics and Psychobiology) 6C. History (including Art History) 60. Philosophy (including Humanities) -

AVIATIONLEGENDS MAGAZINE 2014 AVIATOR LEGENDS Stories of Extraordinary Adventure from This Year’S Thirteen Honorees

AVIATIONLEGENDS MAGAZINE 2014 AVIATOR LEGENDS Stories of extraordinary adventure from this year’s thirteen honorees. A special publication of BE A SPONSOR ! Over 200,000 Attendees — 28% of State! Arctic Thunder — Still the Largest Single Event in Alaska ! Thanks to all Past Sponsors Be Part of it! Alaska Air Show Association an Alaska 501(c) 3 Non-profit All Donations Tax Deductible — AASA Mission — Provide Aviation Education, Inspiration, and Advocacy AASA Provides Scholarships Space Camps, UAA Pilot Training AASA is Civilian Partner to JBER Supporting Arctic Thunder AASA supports Air Events Statewide Arctic Thunder 2016 Starts Now! — Be a Sponsor — Receive Statewide Print, Radio, Internet and TV Exposure plus Day of the Event Seating and pre- and post-event recognition Email : [email protected] Want to Help Advance Aviation? — Join our all Volunteer Board Contents Lake Hood, Photo by Rob Stapleton 5 EDITOR’S LETTER 16 WIllIAM “BIll” DIEHL 36 RON SHEARDOWN Aviation Pioneers Aircraft Manufacturer Polar Adventurer and Rescue Legend 7 WALT AUDI 20 GARLAND DOBSON 40 WARREN THOMPSON Pilot of the Far North Dedicated Serviceman and Pilot Rescue Mission Legend and Teacher 11 ALBERT BAll, SR. 24 JOYCE GAlleHER 43 NOel MERRIll WIEN This year’s Alaska Aviation Legend program Life of Adventure in Rural Alaska Diversified and Experienced Pilot is dedicated to Albert Ball, Sr. and his adventurous spirit. 28 ROYCE MORGAN 47 KENNETH GENE ZERKel Airline Entrepreneur and Doctor Experienced Pilot and Aviation 12 DICK AND LAVelle BETZ Entrepreneur Longtime Alaska Guides 32 PAUL SHANAHAN True Alaskan Bush Pilot 4 EDITOR’S Letter Aviation Pioneers BY ROB STAPLETON n your hands is documentation of hun- abbreviations. -

Flight Safety Digest April 1991

Use of Flight Data Recorders To Prevent Accidents in the U.S.S.R. Analysis of flight recorder information has proven a valuable tool both for investigating accidents and improving the level of flight safety since 1965. by Dr. V. D. Kofman, Deputy Director Scientific Research Laboratory State Supervisory Commission for Flight Safety of the Council of Ministers of the U.S.S.R. (Gosavianadzor) Civil aviation flight safety in the U.S.S.R. is for objective control of technical flight charac- one of the most important challenges that con- teristics of the aircraft and the recording of fronts designers, manufacturers and operators acoustic information aboard civil aircraft in of aviation equipment. Measures directed to- the U.S.S.R. began approximately 25 years ago. ward safety improvements include continu- The first recording devices were primitive ous improvement in the construction of air- emergency data recorders with a limited amount craft and equipment, improvement of opera- of recorded information. At present, the U.S.S.R. tional parameters of critical equipment com- uses modern modular systems for recording ponents in case of emergencies, and improve- and storing information with unlimited possi- ment of professional training of flight crews. bilities for further expansion. They satisfy the airworthiness standards in this country as well The recording and analysis of objective infor- as abroad. mation about the “airplane/flight crew/envi- ronment” system are important to the solu- Since 1965, 12-channel flight data recorders of tion of these problems. At present, flight pa- the MSRP-12 type and their modifications have rameters and crew member conversations are been installed in civil aircraft of the U.S.S.R recorded, along with the corresponding pa- for the storage of flight accident information. -

Air Safety in Southwest Alaska Capstone Baseline Safety Report

FAA Capstone Program Baseline Report April 2001 Air Safety in Southwest Alaska Capstone Baseline Safety Report prepared by: Matthew Berman Alexandra Hill Leonard Kirk Stephanie Martin prepared for: Federal Aviation Administration Alaska Region January 2001 Institute of Social and Economic Research University of Alaska 3211 Providence Drive Anchorage, Alaska 99508 FAA Capstone Program Baseline Report April 2001 Table of Contents 1. Introduction ....................................................................................................................................1 1.1. Purpose of Study.....................................................................................................................1 1.2. Description of the Capstone Area...........................................................................................2 1.3. Air Operations In The Capstone Area ....................................................................................2 1.3. Air Operations In The Capstone Area ....................................................................................3 1.4. Review of Recent Studies.......................................................................................................3 2. Aviation Accidents and Incidents in the Capstone Area ................................................................5 2.1. Summary.................................................................................................................................5 2.2. Accidents in Alaska and the Capstone area ............................................................................5 -

An Integrative Assessment of the Commercial Air Transportation System Via Adaptive Agents

AN INTEGRATIVE ASSESSMENT OF THE COMMERCIAL AIR TRANSPORTATION SYSTEM VIA ADAPTIVE AGENTS A Dissertation Presented to The Academic Faculty by Choon Giap Lim In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy School of Aerospace Engineering Georgia Institute of Technology December 2008 Copyright c 2008 by Choon Giap Lim AN INTEGRATIVE ASSESSMENT OF THE COMMERCIAL AIR TRANSPORTATION SYSTEM VIA ADAPTIVE AGENTS Approved by: Dr. Dimitri N. Mavris, Advisor Dr. Daniel Schrage School of Aerospace Engineering School of Aerospace Engineering Georgia Institute of Technology Georgia Institute of Technology Dr. Jung-Ho Lewe Mr. Kurt Neitzke School of Aerospace Engineering Langley Research Center Georgia Institute of Technology National Aeronautics and Space Ad- ministration (NASA) Dr. Hojong Baik Department of Civil, Architectural and Environmental Engineering Missouri University of Science and Technology Date Approved: August 22, 2008 To my family, for their love, patience, and unwavering support iii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I would like to extend thanks to my adviser, Dr. Dimitri Mavris, who has provided invaluable advice, encouragement, and support throughout the years. To Dr. Jung- Ho Lewe, for his guidance in the research work for this dissertation. To Mr. Kurt Neitzke, Dr. Hojong Baik, and Dr. Daniel Schrage, for sharing their wealth of knowledge. To Dr. Daniel DeLaurentis and Dr. Elena Garcia for their mentorship during my early years at Georgia Tech. I would like to also thank my friends, Eunsuk, Timothy, Xin Yuan, and Joseph, who have helped carry me along in this journey, shared with me their knowledge and most importantly their friendship. Most importantly, I owe what I have achieved today to the unwavering support from my parents, Victor and Anne, who have given me the inspiration and confidence from the very beginning and continued to support me till the end. -

Predation, Competition and Antitrust Law: Turbulence in the Airline Industry Paul Stephen Dempsey

Journal of Air Law and Commerce Volume 67 | Issue 3 Article 4 2002 Predation, Competition and Antitrust Law: Turbulence in the Airline Industry Paul Stephen Dempsey Follow this and additional works at: https://scholar.smu.edu/jalc Recommended Citation Paul Stephen Dempsey, Predation, Competition and Antitrust Law: Turbulence in the Airline Industry, 67 J. Air L. & Com. 685 (2002) https://scholar.smu.edu/jalc/vol67/iss3/4 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Law Journals at SMU Scholar. It has been accepted for inclusion in Journal of Air Law and Commerce by an authorized administrator of SMU Scholar. For more information, please visit http://digitalrepository.smu.edu. PREDATION, COMPETITION & ANTITRUST LAW: TURBULENCE IN THE AIRLINE INDUSTRY* PAUL STEPHEN DEMPSEY** TABLE OF CONTENTS I. INTRODUCTION .................................. 688 II. EMPIRICAL EVIDENCE OF PREDATION ......... 692 A. HUB CONCENTRATION .......................... 692 B. MEGACARRIER ALLIANCES ....................... 700 C. EXAMPLES OF PREDATORY PRICING By MAJOR AIRLINES ........................................ 702 1. Major Network Airline Competitive Response To Entry By Another Major Network Airline ...... 715 a. Denver-Philadelphia: United vs. U SA ir .................................. 716 b. Minneapolis/St. Paul - Cleveland: Northwest vs. Continental ............. 717 2. Major Network Airline Competitive Response To Entry By Southwest Airlines .................. 718 a. St. Louis-Cleveland: TWA vs. Southwest .............................. 719 * Copyright © 2002 by the author. The author would like to thank Professor Robert Hardaway for his contribution to the portion of this essay addressing the essential facility doctrine. The author would also like to thank Sam Addoms and Bob Schulman, CEO and Vice President, respectively, of Frontier Airlines for their invaluable assistance in reviewing and commenting on the case study contained herein involving monopolization of Denver. -

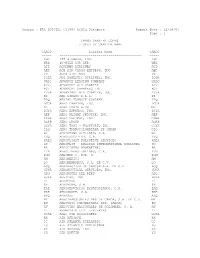

FAA DOT/TSC CY1997 ACAIS Database Report Date : 12/18/97 Page : 1

Source : FAA DOT/TSC CY1997 ACAIS Database Report Date : 12/18/97 Page : 1 CARGO CARRIER CODES LISTED BY CARRIER NAME CARCD Carrier Name CARCD ----- ------------------------------------------ ----- KHC 135 AIRWAYS, INC. KHC WRB 40-MILE AIR LTD. WRB ACD ACADEMY AIRLINES ACD AER ACE AIR CARGO EXPRESS, INC. AER VX ACES AIRLINES VX IQDA ADI DOMESTIC AIRLINES, INC. IQDA UALC ADVANCE LEASING COMPANY UALC ADV ADVANCED AIR CHARTER ADV ACI ADVANCED CHARTERS INT ACI YDVA ADVANTAGE AIR CHARTER, INC. YDVA EI AER LINGUS P.L.C. EI TPQ AERIAL TRANSIT COMPANY TPQ DGCA AERO CHARTER, INC. DGCA ML AERO COSTA RICA ML DJYA AERO EXPRESS, INC. DJYA AEF AERO FLIGHT SERVICE, INC. AEF GSHA AERO FREIGHT, INC. GSHA AGRP AERO GROUP AGRP CGYA AERO TAXI - ROCKFORD, INC. CGYA CLQ AERO TRANSCOLOMBIANA DE CARGA CLQ G3 AEROCHAGO AIRLINES, S.A. G3 EVQ AEROEJECUTIVO, C.A. EVQ XAES AEROFLIGHT EXECUTIVE SERVICES XAES SU AEROFLOT - RUSSIAN INTERNATIONAL AIRLINES SU AR AEROLINEAS ARGENTINAS AR LTN AEROLINEAS LATINAS, C.A. LTN ROM AEROMAR C. POR. A. ROM AM AEROMEXICO AM QO AEROMEXPRESS, S.A. DE C.V. QO ACQ AERONAUTICA DE CANCUN S.A. DE C.V. ACQ HUKA AERONAUTICAL SERVICES, INC. HUKA ADQ AERONAVES DEL PERU ADQ HJKA AEROPAK, INC. HJKA PL AEROPERU PL 6P AEROPUMA, S.A. 6P EAE AEROSERVICIOS ECUATORIANOS, C.A. EAE KRE AEROSUCRE, S.A. KRE ASQ AEROSUR ASQ MY AEROTRANSPORTES MAS DE CARGA, S.A. DE C.V. MY ZU AEROVAIS COLOMBIANAS LTD. (ARCA) ZU AV AEROVIAS NACIONALES DE COLOMBIA, S. A. AV ZL AFFRETAIR LTD. (PRIVATE) ZL UCAL AGRO AIR ASSOCIATES UCAL RK AIR AFRIQUE RK CC AIR ATLANTA ICELANDIC CC LU AIR ATLANTIC DOMINICANA LU AX AIR AURORA, INC. -

A List of Alaska Department of Education Equity Publications; and a Fredback Form

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 376 270 CE 067 142 AUTHOR Dordan, Mary Lou; Nicholson, Deborah TITLE Women and Minorities in Alaskan Aviation. Alaskan Equity Publication. INSTITUTION Alaska State Dept. of Education, Juneau. PUB DATE 94 NOTE 131p. AVAILABLE FROMGender Equity Specialist, Department of Education, 801 West 10th Street, Suite 200, Juneau, AK 99801-1894 ($4 in-state, $6 out-of-state, plus 10% shipping and handling). PUB TYPE Guides Classroom Use Teaching Guides (For Teacher) (052) Tests/Evaluation Instruments (160) EDRS PRICE MF01/PC06 Plus Postage. DESCRIPTORS *Aircraft Pilots; Alaska Natives; *Aviation Education; Career Awareness; Classroom Techniques; Educational Resiurces; *Females; History; Learning Activities; *Minority Groups; Secondary Education; Sex Fairness; *Teaching Methods IDENTIFIERS *Alaska ABSTRACT This resource guide tells the story of Alaskan women and minority aviators and those in aviation-related businesses, from the early 20th century to the present. Developed for secondary students but also suitable for younger students, the guide combines six accounts of Alaskan women and minority aviators with classroom activities centered around the materials. Classroom materials include learning activities such as research questions, puzzles, and art projects. The first three sections of the guide cover early aviation, aviation careers, and aviation safety. A section of curriculum materials for teachers includes the general aviation story, uses of the general aviation airplane, and an aircraft classification chart. Section V contains -

Ntsb/Aar-91/02 Pb91-910402

T PB91-910402 NTSB/AAR-9 l/O2 NATIONAL TRANSPORTATION SAFETY BOARD AIRCRAFI’ ACCIDENT REPORT MARKAIR, INC. BOEING 737-2X6C, N670MA CONTROLLED FLIGHT INTO TERRAIN UNALAKLEET, ALASKA JUNE 2, 1990 5358A NTSB Report No.: NTSB/AAR-9 l/O2 NTIS No.‘: PB91-910402 Report Date: January 23,199l Notation No.: 535BA Title: Aircraft Accident Report: MarkAir, Inc., Boeing 737-2X6C, N670MA, Controlled Flight into Terrain, Unalakleet, Alaska, June 2,199O Organization: National Transportation Safety Board Office of Aviation Safety Washington, D.C. 20594 Type of Report: Aircraft Accident Report Period Covered: June 2,199O Abstract: This report explains the crash of a MarkAir Boeing 737-2X6C at Unalakleet, Alaska, on June 2, 1990. The safety issues discussed in the report are cockpit resource management and approach chart symbology. Recommendations addressing these issues were made to Federal Aviation Administration and MarkAir, Inc. The National Transportation Safety Board is an independent Federal agency dedicated to promoting aviation, railroad, highway, marine, pipeline, and hazardous materials safety. Established in 1967, the agency is mandated by the Independent Safet Board Act of 1974 to investigate transportation accidents, determine the proii able cause of accidents, issue safety recommendations, study transportation safety issues, and evaluate the safety effectiveness of government agencies involved in transportation. The Safety Board makes public its actions and decisions through accident reports, safety studies, special investigation reports, safety recommendations, and statistical reviews. Copies of these documents may be purchased from the National Technical Information Service, 5285 Port Royal Road, Springfield, Virginia 22161. Details on available publications may be obtained by contacting: National Transportation Safety Board Public Inquiries Section, RE-51 800 Independence Avenue, S.W.