Woodstock: the Creation and Evolution of a Myth

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

On This Date Daily Trivia Happy Birthday! Quote of The

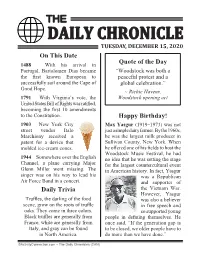

THE TUESDAY, DECEMBER 15, 2020 On This Date 1488 – With his arrival in Quote of the Day Portugal, Bartolomeu Dias became “Woodstock was both a the first known European to peaceful protest and a successfully sail around the Cape of global celebration.” Good Hope. ~ Richie Havens, 1791 – With Virginia’s vote, the Woodstock opening act United States Bill of Rights was ratified, becoming the first 10 amendments to the Constitution. Happy Birthday! 1903 – New York City Max Yasgur (1919–1973) was not street vendor Italo just a simple dairy farmer. By the 1960s, Marchiony received a he was the largest milk producer in patent for a device that Sullivan County, New York. When molded ice-cream cones. he offered one of his fields to host the Woodstock Music Festival, he had 1944 – Somewhere over the English no idea that he was setting the stage Channel, a plane carrying Major for the largest countercultural event Glenn Miller went missing. The in American history. In fact, Yasgur singer was on his way to lead his was a Republican Air Force Band in a concert. and supporter of Daily Trivia the Vietnam War. However, Yasgur Truffles, the darling of the food was also a believer scene, grow on the roots of truffle in free speech and oaks. They come in three colors. so supported young Black truffles are generally from people in defining themselves. He France, white are generally from once said, “If the generation gap is Italy, and gray can be found to be closed, we older people have to in North America. -

B2 Woodstock – the Greatest Music Event in History LIU030

B2 Woodstock – The Greatest Music Event in History LIU030 Choose the best option for each blank. The Woodstock Festival was a three-day pop and rock concert that turned out to be the most popular music (1) _________________ in history. It became a symbol of the hippie (2) _________________ of the 1960s. Four young men organized the festival. The (3) _________________ idea was to stage a concert that would (4) _________________ enough money to build a recording studio for young musicians at Woodstock, New York. Young visitors on their way to Woodstock At first many things went wrong. People didn't want Image: Ric Manning / CC BY (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/3.0) any hippies and drug (5) _________________ coming to the original location. About 2 months before the concert a new (6) _________________ had to be found. Luckily, the organizers found a 600-acre large dairy farm in Bethel, New York, where the concert could (7) _________________ place. Because the venue had to be changed not everything was finished in time. The organizers (8) _________________ about 50,000 people, but as the (9) _________________ came nearer it became clear that far more people wanted to be at the event. A few days before the festival began hundreds of thousands of pop and rock fans were on their (10) _________________ to Woodstock. There were not enough gates where tickets were checked and fans made (11) _________________ in the fences, so lots of people just walked in. About 300,000 to 500,000 people were at the concert. The event caused a giant (12) _________________ jam. -

August Highlights at the Grant Park Music Festival

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE Contact: Jill Hurwitz,312.744.9179 [email protected] AUGUST HIGHLIGHTS AT THE GRANT PARK MUSIC FESTIVAL A world premiere by Aaron Jay Kernis, an evening of mariachi, a night of Spanish guitar and Beethoven’s Ninth Symphony on closing weekend of the 2017 season CHICAGO (July 19, 2017) — Summer in Chicago wraps up in August with the final weeks of the 83rd season of the Grant Park Music Festival, led by Artistic Director and Principal Conductor Carlos Kalmar with Chorus Director Christopher Bell and the award-winning Grant Park Orchestra and Chorus at the Jay Pritzker Pavilion in Millennium Park. Highlights of the season include Legacy, a world premiere commission by the Pulitzer Prize- winning American composer, Aaron Jay Kernis on August 11 and 12, and Beethoven’s Symphony No. 9 with the Grant Park Orchestra and Chorus and acclaimed guest soloists on closing weekend, August 18 and 19. All concerts take place on Wednesday and Friday evenings at 6:30 p.m., and Saturday evenings at 7:30 p.m. (Concerts on August 4 and 5 move indoors to the Harris Theater during Lollapolooza). The August program schedule is below and available at www.gpmf.org. Patrons can order One Night Membership Passes for reserved seats, starting at $25, by calling 312.742.7647 or going online at gpmf.org and selecting their own seat down front in the member section of the Jay Pritzker Pavilion. Membership support helps to keep the Grant Park Music Festival free for all. For every Festival concert, there are seats that are free and open to the public in Millennium Park’s Seating Bowl and on the Great Lawn, available on a first-come, first-served basis. -

A Turf of Their Own

HAVERFORD COLLEGE HISTORY DEPARTMENT A Turf of Their Own The Experiments and Contradictions of 1960s Utopianism David Ivy-Taylor 4/22/2011 Submitted to James Krippner in partial fulfillment of History 400: Senior Thesis Seminar Table of Contents Abstract 3 Acknowledgements 4 INTRODUCTION 5 Historical Problem 5 Historical Background 7 Sources 14 AN AQUARIAN EXPOSITION 16 The Event 16 The Myth 21 Historical Significance 25 DISASTER AT ALTAMONT .31 The Event 31 Media Coverage 36 Historical Significance 38 PEOPLE'S PARK: "A TURF OF THEIR OWN" 40 The Event 40 Media Coverage 50 Historical Significance 51 THE SAN FRANCISCO DIGGERS, COMMUNES, AND THE HUMAN BE-IN 52 Communes 52 The Diggers 54 San Francisco 55 CONCLUSIONS 59 BIBLIOGRAPHY 61 2 ABSTRACT After WWII, the world had to adjust to new technologies, new scientific concepts, new political realities, and new social standards. While America was economically wealthy after the war, it still had to deal with extremely difficult social and cultural challenges. Due to these new aspects of life, there were increasing differences in both the interests and values of children and their parents, what we have learned to call the "generation gap". The "generational gap" between the youth culture and their parents meant a polarizing society, each hating and completely misunderstanding the other.. This eventually resulted in a highly political youth culture that was laterally opposed to the government. Through isolation, the counterculture began to develop new philosophies and new ways of thinking, and a huge part of that philosophy was the pursuit of a "Good Society", a utopian dream for world peace. -

ANDERTON Music Festival Capitalism

1 Music Festival Capitalism Chris Anderton Abstract: This chapter adds to a growing subfield of music festival studies by examining the business practices and cultures of the commercial outdoor sector, with a particular focus on rock, pop and dance music events. The events of this sector require substantial financial and other capital in order to be staged and achieve success, yet the market is highly volatile, with relatively few festivals managing to attain longevity. It is argued that these events must balance their commercial needs with the socio-cultural expectations of their audiences for hedonistic, carnivalesque experiences that draw on countercultural understanding of festival culture (the countercultural carnivalesque). This balancing act has come into increased focus as corporate promoters, brand sponsors and venture capitalists have sought to dominate the market in the neoliberal era of late capitalism. The chapter examines the riskiness and volatility of the sector before examining contemporary economic strategies for risk management and audience development, and critiques of these corporatizing and mainstreaming processes. Keywords: music festival; carnivalesque; counterculture; risk management; cool capitalism A popular music festival may be defined as a live event consisting of multiple musical performances, held over one or more days (Shuker, 2017, 131), though the connotations of 2 the word “festival” extend much further than this, as I will discuss below. For the purposes of this chapter, “popular music” is conceived as music that is produced by contemporary artists, has commercial appeal, and does not rely on public subsidies to exist, hence typically ranges from rock and pop through to rap and electronic dance music, but excludes most classical music and opera (Connolly and Krueger 2006, 667). -

From Del Ray to Monterey Pop Festival

Office of Historic Alexandria City of Alexandria, Virginia Out of the Attic From Del Ray to Monterey Pop Festival Alexandria Times, February 11, 2016 Image: The Momas and the Popas. Photo, Office of Historic Alexandria. t the center of Alexandria’s connection to rock and folk music fame was John Phillips. Born in South A Carolina, John and his family lived in Del Ray for much of his childhood. He attended George Washington High School, like Cass Elliot and Jim Morrison, graduating in 1953. He met and then married his high school sweetheart, Susie Adams, with whom he had two children, Jeffrey and Mackenzie, who later became famous in her own right. Phillips and Adams lived in the Belle Haven area after high school, but John left his young family at their Fairfax County home to start a folk music group called the Journeymen in New York City. The new group included lifelong friend and collaborator Philip Bondheim, later known as Scott McKenzie, also from Del Ray. The young men had met through their mothers, who were close friends. While in New York, John’s romantic interests turned elsewhere and he told Susie he would not be returning to her. Soon after, he married his second wife, Michelle Gilliam, who was barely out of her teens. They had one daughter, Chynna, who also gained fame as a singer. Gilliam and Phillips joined two former members of a group called the Mugwumps, Denny Doherty and Cass Elliot to form The Mamas and the Papas in 1965. This photo from that time shows Gilliam and Doherty to the left, Phillips and Elliot to the right, and fellow Alexandrian Bondheim at the center. -

Bohemian Space and Countercultural Place in San Francisco's Haight-Ashbury Neighborhood

University of Central Florida STARS Electronic Theses and Dissertations, 2004-2019 2017 Hippieland: Bohemian Space and Countercultural Place in San Francisco's Haight-Ashbury Neighborhood Kevin Mercer University of Central Florida Part of the History Commons Find similar works at: https://stars.library.ucf.edu/etd University of Central Florida Libraries http://library.ucf.edu This Masters Thesis (Open Access) is brought to you for free and open access by STARS. It has been accepted for inclusion in Electronic Theses and Dissertations, 2004-2019 by an authorized administrator of STARS. For more information, please contact [email protected]. STARS Citation Mercer, Kevin, "Hippieland: Bohemian Space and Countercultural Place in San Francisco's Haight-Ashbury Neighborhood" (2017). Electronic Theses and Dissertations, 2004-2019. 5540. https://stars.library.ucf.edu/etd/5540 HIPPIELAND: BOHEMIAN SPACE AND COUNTERCULTURAL PLACE IN SAN FRANCISCO’S HAIGHT-ASHBURY NEIGHBORHOOD by KEVIN MITCHELL MERCER B.A. University of Central Florida, 2012 A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in the Department of History in the College of Arts and Humanities at the University of Central Florida Orlando, Florida Summer Term 2017 ABSTRACT This thesis examines the birth of the late 1960s counterculture in San Francisco’s Haight-Ashbury neighborhood. Surveying the area through a lens of geographic place and space, this research will look at the historical factors that led to the rise of a counterculture here. To contextualize this development, it is necessary to examine the development of a cosmopolitan neighborhood after World War II that was multicultural and bohemian into something culturally unique. -

On the Road with Janis Joplin Online

6Wgt8 (Download) On the Road with Janis Joplin Online [6Wgt8.ebook] On the Road with Janis Joplin Pdf Free John Byrne Cooke *Download PDF | ePub | DOC | audiobook | ebooks Download Now Free Download Here Download eBook #893672 in Books John Byrne Cooke 2015-11-03 2015-11-03Original language:EnglishPDF # 1 8.25 x .93 x 5.43l, 1.00 #File Name: 0425274128448 pagesOn the Road with Janis Joplin | File size: 33.Mb John Byrne Cooke : On the Road with Janis Joplin before purchasing it in order to gage whether or not it would be worth my time, and all praised On the Road with Janis Joplin: 1 of 1 people found the following review helpful. A Must Read!!By marieatwellI have read all but maybe 2 books on the late Janis Joplin..by far this is one of the Best I have read..it showed the "music" side of Janis,along with the "personal" side..great book..Highly Recommended,when you finish this book you feel like you've lost a band mate..and a friend..she could have accomplished so much in the studio,such as producing her own records etc..This book is excellent..0 of 0 people found the following review helpful. Thank-you John for a very enjoyable book.By Mic DAs a teen in 1969 and growing up listening to Janis and all the bands of the 60's and 70's, this book was very enjoyable to read.If you ever wondered what it might be like to be a road manager for Janis Joplin, John Byrne Cooke answers it all.Those were extra special days for all of us and John's descriptions of his experiences, helps to bring back our memories.Thank-you John for a very enjoyable book.0 of 0 people found the following review helpful. -

The Paul Butterfield Blues Band Run out of Time / One More Heartache Mp3, Flac, Wma

The Paul Butterfield Blues Band Run Out Of Time / One More Heartache mp3, flac, wma DOWNLOAD LINKS (Clickable) Genre: Rock / Blues Album: Run Out Of Time / One More Heartache Country: Italy Released: 1967 MP3 version RAR size: 1399 mb FLAC version RAR size: 1963 mb WMA version RAR size: 1820 mb Rating: 4.5 Votes: 635 Other Formats: APE MOD DMF ADX DXD VOX MP1 Tracklist Hide Credits Run Out Of Time A Written-By – Peterson*, Butterfield* One More Hearrtache B Written-By – Tarplin*, Rogers*, White*, Robinson*, Moore* Other versions Category Artist Title (Format) Label Category Country Year The Paul Butterfield Run Out Of Time (7", EK-45620 Elektra EK-45620 US 1967 Blues Band Single, Promo) The Paul Butterfield EKSN 45020 Run Out Of Time (7") Elektra EKSN 45020 UK 1967 Blues Band Run Out Of Time / The Paul Butterfield EK 45620 One More Heartache Elektra EK 45620 Canada 1967 Blues Band (7") The Paul Butterfield Run Out Of Time (7", EK-45620 Elektra EK-45620 US Unknown Blues Band Single) The Paul Butterfield Run Out Of Time (7", EK-45620 Elektra EK-45620 US 1967 Blues Band Single) Related Music albums to Run Out Of Time / One More Heartache by The Paul Butterfield Blues Band Paul Butterfield Blues Band, The - run out of time Butterfield Blues Band - Where Did My Baby Go The Butterfield Blues Band - The Resurrection Of Pigboy Crabshaw The Paul Butterfield Blues Band - Golden Butter / The Best Of The Paul Butterfield Blues Band Ray Conniff, Billy Butterfield - Conniff Meets Butterfield Billy Butterfield And Ray Conniff - Conniff Meets Butterfield The Paul Butterfield Blues Band - The Paul Butterfield Blues Band The Butterfield Blues Band - Keep On Moving The Paul Butterfield Blues Band - An Anthology: The Elektra Years Various - Elektra March Releases Various - What's Shakin' The Paul Butterfield Blues Band - Run Out Of Time. -

The Road to Woodstock Free

FREE THE ROAD TO WOODSTOCK PDF Michael Lang,Holly George-Warren | 352 pages | 15 Jul 2010 | HarperCollins Publishers Inc | 9780061576584 | English | New York, United States On the Road Again - ExtremeTech Janis Joplin is one of the most famous musicians of her era, creating and performing soulful songs like "Piece of my Heart" and The Road to Woodstock and Bobby McGee". She tragically died at the age of The Vietnam War bitterly divided the United States during the s and s, and it drastically impacted the music scene. Some of the most iconic musicians at Woodstock were known for their protest songs. Carlos Santana's signature sound is an infectious blend of rock and roll and Latin jazz. Santana is still popular today, pairing up with artists such as Rob Thomas on catchy tunes. The Who was one of the biggest names at Woodstock. They have an impressive roster of chart-topping albums, including fan-favorite "Tommy. The unique sound of Creedence Clearwater Revival, or CCR to their fans, is so catchy that the band remains popular today. Their work has been used in movies and television shows for decades. He played this plus many more incredible songs at Woodstock. Jefferson Airplane has gone through many transformations in their time, becoming Jefferson Starship and then Starship in later decades. During Woodstock, Jefferson Airplane was rocking out in their original name. Woodstock was held in The Road to Woodstock, New York. Specifically, it was held on Max Yasgur's dairy farm. Joan Baez wrote and performed some of the most iconic protest music from the s, including her soulful rendition of Bob Dylan's "Blowin' In The Wind. -

Live Music Matters Scottish Music Review

Live Music Matters Simon Frith Tovey Professor of Music, University of Edinburgh Scottish Music Review Abstract Economists and sociologists of music have long argued that the live music sector must lose out in the competition for leisure expenditure with the ever increasing variety of mediated musical goods and experiences. In the last decade, though, there is evidence that live music in the UK is one of the most buoyant parts of the music economy. In examining why this should be so this paper is divided into two parts. In the first I describe why and how live music remains an essential part of the music industry’s money making strategies. In the second I speculate about the social functions of performance by examining three examples of performance as entertainment: karaoke, tribute bands and the Pop Idol phenomenon. These are, I suggest, examples of secondary performance, which illuminate the social role of the musical performer in contemporary society. 1. The Economics of Performance Introduction It has long been an academic commonplace that the rise of mediated music (on record, radio and the film soundtrack) meant the decline of live music (in concert hall, music hall and the domestic parlour). For much of the last 50 years the UK’s live music sector, for example, has been analysed as a sector in decline. Two kinds of reason are adduced for this. On the one hand, economists, following the lead of Baumol and Bowen (1966), have assumed that live music can achieve neither the economies of scale nor the reduction of labour costs to compete with mass entertainment media. -

Living Blues 2021 Festival Guide

Compiled by Melanie Young Specific dates are provided where possible. However, some festivals had not set their 2021 dates at press time. Due to COVID-19, some dates are tentative. Please contact the festivals directly for the latest information. You can also view this list year-round at www.LivingBlues.com. Living Blues Festival Guide ALABAMA Foley BBQ & Blues Cook-Off March 13, 2021 Blues, Bikes & BBQ Festival Juneau Jazz & Classics Heritage Park TBA TBA Foley, Alabama Alabama International Dragway Juneau, Alaska 251.943.5590 2021Steele, Alabama 907.463.3378 www.foleybbqandblues.net www.bluesbikesbbqfestival.eventbrite.com jazzandclassics.org W.C. Handy Music Festival Johnny Shines Blues Festival Spenard Jazz Fest July 16-27, 2021 TBA TBA Florence, Alabama McAbee Activity Center Anchorage, Alaska 256.766.7642 Tuscaloosa, Alabama spenardjazzfest.org wchandymusicfestival.com 205.887.6859 23rd Annual Gulf Coast Ethnic & Heritage Jazz Black Belt Folk Roots Festival ARIZONA Festival TBA Chandler Jazz Festival July 30-August 1, 2021 Historic Greene County Courthouse Square Mobile, Alabama April 8-10, 2021 Eutaw, Alabama Chandler, Arizona 251.478.4027 205.372.0525 gcehjazzfest.org 480.782.2000 blackbeltfolkrootsfestival.weebly.com chandleraz.gov/special-events Spring Fling Cruise 2021 Alabama Blues Week October 3-10, 2021 Woodystock Blues Festival TBA May 8-9, 2021 Carnival Glory Cruise from New Orleans, Louisiana Tuscaloosa, Alabama to Montego Bay, Jamaica, Grand Cayman Islands, Davis Camp Park 205.752.6263 Bullhead City, Arizona and Cozumel,