Diego Garcia Yellowfin Tuna Tagging Expedition Final

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

NOTE on the Fishery and Some Aspects of the Biology of Dogtooth Tuna, Gymnosarda Unicolor (Ruppell)From Minicoy, Lakshadweep

I. mar. biol. Ass. India, 47 (1) : 111 - 113, Jan. - June, 2005 NOTE On the fishery and some aspects of the biology of dogtooth tuna, Gymnosarda unicolor (Ruppell)from Minicoy, Lakshadweep M.Sivadas and A.Anasukoya Research Centre of Central Marine Fisheries Research Institute, Calicut - 673 005, India Abstract The results of a study, on the fishery and biology of dogtooth tuna, Gymnosarda unicolor (Ruppell), conducted at Minicoy during 1995 to 1999 are presented. The resource is exploited from around the reef areas during July-August or September for sustenance when the usual fishing activities like pole and line and trolling are suspended. The total catch in a season varied from 56 to 481 kg. The size ranged from 44 to 126 cm fork length with the modal group at 58 and 62 cm. The length-weight relationship was found to be Log W = -4.5337 + 2.77 Log L. Fish below 70 cm size was found to be immature. The dogtooth tuna, Gymnosarda unicolor Material and methods (Ruppell) is a tropical Indo-Pacific epipe- Data on catch and biological aspects lagic species usually found around coral such as length, weight, feeding condition, reefs. In India, they are reported from maturity, etc were collected almost on a Andaman-Nicobar and from daily basis at the landing centre itself Lakshadweep Islands (Silas and Pillai, during each season. The entrails of the 1982). In Lakshadweep, they are not fishes are removed at the landing centre exploited by pole and line and troll line but are caught regularly, though in few itself before they are taken home. -

India's National Report to the Scientific Committee of the Indian Ocean

IOTC–2015–SC18–NR09[E] India’s National Report to the Scientific Committee of the Indian Ocean Tuna Commission’2015 Premchand, L. Ramalingam, A. Tiburtius, A. Siva, Ansuman Das, Rajashree B Sanadi and Rahul Kumar B Tailor Fishery Survey of India Government of India, Botawala Chambers, Sir. P. M. Road, Mumbai 0 INFORMATION OF FISHERIES, RESEARCH AND STATISTICS In accordance with IOTC Resolution 15/02, final YES scientific data for the previous year was Communication F.No.43-6/2014 Fy. II, dated provided to the Secretariat by June of the 03/07/2015 to the Ministry of Agriculture and current year, for all fleets other than Farmer’s Welfare, New Delhi. longline(e.g., for a National report submitted to the Secretariat in 2015, final data for the 2014 Calendar year must be provided to the Secretariat by 30 June’2015) In accordance with IOTC Resolution 15/02, YES provisional longline data for the previous year Communication F.No.43-6/2014 Fy.II, was provided to the Secretariat by 30 June of 03/07/2015 to the Ministry of Agriculture and the current year (e.g., for a National report Farmer’s Welfare, New Delhi. submitted to the Secretariat in 2015, final data for the 2014 Calendar year must be provided to the Secretariat by 30 June’2015) Reminder: Final longline data for the previous year is due to the Secretariat by 30 December of the current year (e.g., for a National report submitted to the Secretariat in 2015, final data for the 2014 Calendar year must be provided to the Secretariat by 30 June’2015) If no, please indicate the reason(s) and intended actions: - Executive Summary Tuna and tuna like fishes are one of the components of pelagic resources. -

TUNA FISHERY in KENY a Prepared by Dorcus Sigana National Component 4

IOTC-2009-SC-INF09 TUNA FISHERY IN KENY A prepared by Dorcus Sigana National Component 4 In Kenya, Tuna fishery is carried out artisanally and industrially. Artisanal fishermen sell their catch to the domestic market while Industrial fishermen process and export to the European Union market. Fishing is mainly confined to the coastal waters up to 50 meters depth. At Ungwana Bay, fishing has been extended to groups up to 200 meters for deep- water lobsters, prawns and demersal fishes. The larger pelagic fishes comprise the tuna and tuna-like species and the larger carangids, which are caught in large numbers between 15–200 meters depth mostly in June and July. Surveys on marine fisheries resources of Kenya dates back from 1951 when the East African Marine Fisheries Research Organization was formed, during which time the emphasis was on pelagic species. During the surveys on pelagic fishes between 1951 and 1954 catches of 0.52 kg/line/hr were obtained. 22% of the total catch was Scomberomorus commerson (Williams, 1956). In the same survey it was observed that tunas, especially the yellow fin tuna Thunnus albacares was present throughout the year, but with marked increase during the Southeast monsoon and very close to the shore up to 4 km off-shore. Other tunas that were found in the area were Albacare Thunnus alalunga, the dogtooth tuna Gymnosarda unicolor, small tuna Euthynnus affinis and skipjack Katsuwonus pelamis. Although these species were found within the Kenya waters they are unexploited. The Norad report states that Tunas are unique among fishes in having limited thermo- regulatory capacity. -

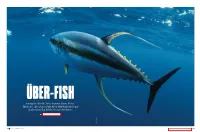

Among the World's Most Popular Game Fishes, Tunas Are Also

ÜBER-FISH Among the World’s Most Popular Game Fishes, Tunas Are Also Some of the Most Highly Evolved and Sophisticated of All the Ocean’s Predators BY DOUG OLANDER DANIEL GOEZ DANIEL 74 DECEMBER 2017 SPORTFISHINGMAG.COM 75 The Family Tree minimizes drag with a very low reduce the turbulence in the Tunas are part of the family drag coefficient,” optimizing effi- water ahead of the tail. Scombridae, which also includes cient swimming both at cruise Unlike most fishes with broad, mackerels, large and small. But and burst. While most fishes bend flexible tails that bend to scoop there are tunas, and then there their bodies side to side when water to move a fish forward, are, well, “true tunas.” moving forward, tunas’ bodies tunas derive tremendous That is, two groups don’t bend. They’re essentially thrust with thin, hard, lunate WHILE MOST FISHES BEND ( sometimes known as “tribes”) rigid, solid torpedoes. ( crescent-moon-shaped) tails dominate the tuna clan. One is And these torpedoes are that beat constantly, capable of THEIR BODIES SIDE TO SIDE Thunnini, which is the group perfectly streamlined, their 10 to 12 or more beats per second. considered true tunas, charac- larger fins fitting perfectly into That relentless thrust accounts WHEN MOVING FORWARD, terized by two separate dorsal grooves so no part of these fins for the unstoppable runs that fins and a relatively thick body. a number of highly specialized protrudes above the body surface. tuna make repeatedly when TUNAS’ BODIES DON’T BEND. The 15 species of Thunnini are features facilitate these They lack the convex eyes of hooked. -

A Global Valuation of Tuna an Update February 2020 (Final)

Netting Billions: a global valuation of tuna an update February 2020 (Final) ii Report Information This report has been prepared with the financial support of The Pew Charitable Trusts. The views expressed in this study are purely those of the authors. The content of this report may not be reproduced, or even part thereof, without explicit reference to the source. Citation: Macfadyen, G., Huntington, T., Defaux, V., Llewellin, P., and James, P., 2019. Netting Billions: a global valuation of tuna (an update). Report produced by Poseidon Aquatic Resources Management Ltd. Client: The Pew Charitable Trusts Version: Final Report ref: 1456-REG/R/02/A Date issued: 7 February 2020 Acknowledgements: Our thanks to the following consultants who assisted with data collection for this study: Richard Banks, Sachiko Tsuji, Charles Greenwald, Heiko Seilert, Gilles Hosch, Alicia Sanmamed, Anna Madriles, Gwendal le Fol, Tomasz Kulikowski, and Benoit Caillart. 7 February 2020 iii CONTENTS 1. BACKGROUND AND INTRODUCTION ................................................................... 1 2. STUDY METHODOLOGY ......................................................................................... 3 3. TUNA LANDINGS ..................................................................................................... 5 3.1 METHODOLOGICAL ISSUES ....................................................................................... 5 3.2 RESULTS ............................................................................................................... -

Little Tuna Euthynnus Affinis in the Hong Kong Area*

Bulletin of the Japanese Society of Scientific Fisheries Vol. 36, No. 1, 1970 9 Little Tuna Euthynnus affinis in the Hong Kong area* Gordon R. WILLIAMSON** (Received September 10, 1969) The Little Tuna Euthynnus affinis CANTOR(Fig . 1) is distributed from the east coast of Africa in the Indian Ocean to Indonesia and Japan across the equatorial Pacific Ocean to Hawaii (Fig. 2). KIKAWA et al.1) and WILLIAMS2) have summarised data on the species in the Pacific and Indian Oceans respectively , TESTER and NAKAMURA3) give additional information from Hawaii, ABE4) gives a good colour illustration of the species and NAKAMURA Fig. 1. Euthynnus affinis CANTOR. and MAGNUSON5) describe periodic changes From NAKAMURAand MAGNUSON5) in intensity of the fish's black spots . The taxonomy of the species, which was formerly called E. yaito by some biologists, is discussed by FRASER-BRUNNER6), COLLETTEand GIBBS7)and NAKAMURA8). A general account of fishery resources around Hong Kong is given by WILLIAMSON9). Fishermen's reports indicate that E. affinis is the commonest tuna in the Hong Kong area. Auxis thazard (LACEPEDE)is the only species with which it can be confused. E. affinis and A. thazard can be separated by the following characters: Fig. 2. Distribution of Euthynnus affinis CANTOR. After KIKAWA et a1.1) and WILLIAMS2)and with the Kwangtung coast added to the distribution range. One specimen of E. affinis has been recorded from California. * Contribution No . 36 from the Fisherier Research Station, Hong Kong. ** Agriculture and Fisheries Department , Fisheries Research Station, Aberdeen, Hong Kong. 10 E. affinis 15-16 dorsal fin rays, transient black spots under pectoral fins A. -

Bigeye Tuna (Thunnus Obesus) and Tuna Fisheries of French Polynesia

BIGEYE TUNA (THUNNUS OBESUS) AND THE Tl1NA FISHERIES OF FRENCH POLYNESIA by Francois Xavier Bard" Erwan Josse', and Arsene Stein2 I. INTRODUCTION French Polynesia has a wide Exclusive Economic Zone (EEZ), established in October 1979, stretching over 4.8 million km2 in the South Pacific, in which most species of tropical tunas and tuna-like species are fished, at the surface or in subsurface waters. The main commercial species are: • Yellowfin tuna iThunnus albacares), caught at the surface and in subsurface waters; • Bigeye tuna (Thunnus obesus), caught only in subsurface waters; • Albacore tuna tThunnus a/a/unga), caught only in subsurface waters; • Blue marlin (Makaira mazara), caught at the surface and in subsurface waters; • Skipjack tuna (Katsuwonus pe/amis), caught only at the surface; • Wahoo (Acanthocybium so/andri), caught only at the surface. Other istiophorids (Tetrapturus audax, T. angustirostris, and Istiophorus platypteruss are also caught at the surface and in subsurface waters. Swordfish (Xiphias gladius) is present, but uncommon. Minor tunas such as black skipjack tEuthynnus aJlinis) and dogtooth tuna (Gymnosarda unicolori are present, but not actively sought. There is a long tradition ofcoastal tuna fishing in French Polynesia. Historically, fishermen in canoes have fished for deep-swimming tunas, using handlines made of vegetable fibers, hooks made of wood and mother-of pearl, and chunks of fish or live fish for bait. Sinking the line was achieved with a stone, around which the line was initially coiled. The fish, caught in precise fishing spots known as "tuna holes," were mainly yellowfin and mana tPrometichthys prometheusv. This "stone fishery," which uses small boats with outboard engines, locally called poti marara, and modem lines and hooks, which generally operate close to fish-aggregating devices (FADs) moored in the vicinity of the larger islands (Moarii and Leproux, 1996), but tuna holes are sometimes fished as well. -

Species Fact Sheets Euthynnus Affinis (Cantor, 1849)

Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations Fisheries and for a world without hunger Aquaculture Department Species Fact Sheets Euthynnus affinis (Cantor, 1849) Black and white drawing: (click for more) Synonyms Euthunnus yaito Kishinouye, 1915 Wanderer wallisi Whitley, 1937 Euthunnus affinis affinis Fraser-Brunner, 1949 Euthunnus alletteratus affinis Beaufort, 1951 Euthunnus wallisi Whitley, 1964 FAO Names En - Kawakawa, Fr - Thonine orientale, Sp - Bacoreta oriental. 3Alpha Code: KAW Taxonomic Code: 1750102406 Scientific Name with Original Description Thynnus affinis Cantor, 1849, J.Asiatic Soc.Bengal, 18(2):1088-1090 (Sea of Penang, Malaysia). Diagnostic Features Gillrakers 29 to 33 on first arch; gill teeth 28 or 29; vomerine teeth absent. Anal fin rays 13 or 14. Vertebrae 39; no trace of vertebral protuberances; bony caudal keels on 33 and 34 vertebrae. Colour: dorsal makings composed of broken oblique stripes. Geographical Distribution FAO Fisheries and Aquaculture Department Launch the Aquatic Species Distribution map viewer Throughout the warm waters of the Indo-West Pacific, including oceanic islands and archipelagos.A few stray specimens have been collected in the eastern tropical Pacific. Habitat and Biology An epipelagic, neritic speciesinhabiting waters temperatures ranging from 18 to 29° C. Like other scombrids, E. affinis tend to form multispecies schools by size, 'i.e. with small Thunnus albacares, Katsuwonus pelamis, Auxis sp., and Megalaspis cordyla (a carangid), comprising from 100 to over 5 000 individuals. Although sexually mature fish may be encountered throughout the year, there are seasonal spawning peaks varying according to regions: i.e. March to May in Philippine waters; during the period of the NW monsoon (October-November to April-May) around the Seychelles; from the middle of the NW monsoon period to the beginning of the SE monsoon (January to July) off East Africa; and probably from August to October off Indonesia. -

The Italian Annotated Bibliography on Small Tunas

SCRS/2020/061 Collect. Vol. Sci. Pap. ICCAT, 77(9): 34-84 (2020) THE ITALIAN ANNOTATED BIBLIOGRAPHY ON SMALL TUNAS C. Piccinetti1, P. Addis2, A. Di Natale3, F. Garibaldi4, F. Tinti5 SUMMARY The Italian scientists have a long tradition of studies and research on many large pelagic species including, among others, the small tunas. The various small tuna species are important for the Italian fishery since many centuries, mostly from a socio-economical point of view. Some non- indigenous species are now present in the ICCAT Convention area. This is the first attempt to list together the many papers published so far by Italian scientists, concerning the biology of these species, the fisheries and many other scientific and cultural issues. The aim of this paper is to provide an annotated bibliography, with specific key words, even if it is surely incomplete, because of the many papers published over the years. This bibliography, which includes 309 annotated citations, was set together to serve the scientists and to help them in finding some rare references that might be useful for their work. RÉSUMÉ Les scientifiques italiens ont une longue tradition d'études et de recherches sur de nombreuses de espèces de grands pélagiques y compris, entre autres, les espèces de thonidés mineurs. Les différentes espèces de thonidés mineurs sont importantes pour la pêche italienne depuis de nombreux siècles, principalement d'un point de vue socio-économique. Certaines espèces non autochtones sont maintenant présentes dans la zone de la Convention de l’ICCAT. Il s'agit de la première tentative de répertorier les nombreux articles publiés à ce jour par des scientifiques italiens concernant la biologie de ces espèces, les pêcheries et de nombreuses autres questions scientifiques et culturelles. -

Follow the Leader

Follow the leader With an eye to the future: addressing failures in the global management of Bigeye Tuna Mary Lack Acknowledgements Mary Lack is a consultant from Shellack Pty Ltd. International Affairs, National Marine Fisheries Service; and Mr. Ray Clarke of the Pacific Islands Regional Office of the National The author acknowledges, with much appreciation, the Marine Fisheries Service. contribution of Glenn Sant (TRAFFIC International) and Lorraine Hitch (WWF Australia) to this report. Officers from the TRAFFIC Preparation of this report was made possible with funding network provided invaluable advice on the availability of trade support from the David and Lucile Packard Foundation. information. Citation: This document should be cited as: Lack, M. (2007). The report also benefited greatly from the helpful and insightful With an eye to the future: addressing failures in the global comments provided by: Adam Langley, Principal Fisheries management of bigeye tuna. TRAFFIC International and WWF Scientist, Oceanic Fisheries Programme, Secretariat of the Australia. Pacific Community; Ms Deirdre Warner-Kramer and Ms Holly Cover photograph: Unloading tuna caught by longline in the Koehler, Office of Marine Conservation, US Department of Western Central Pacific Ocean. © SPC Oceanic Fisheries State; Ms Kelly Denit and Ms Kim Blankenbeker of the Office of Programme / Siosifa Fukofuka. © 2007 TRAFFIC International and WWF Australia. All or in part of this publication must credit WWF Australia and rights reserved TRAFFIC International as the copyright owner. All material appearing in this publication is copyrighted and The views of the authors expressed in this publication do not may be reproduced with permission. Any reproduction in full necessarily reflect those of TRAFFIC, WWF or IUCN. -

Fish Forensics: Two Strategies for Fish Identification

430 Nahant Rd., Nahant, MA, USA 01908 | 781-581-7370 ext. 343 | [email protected] | www.northeastern.edu/ogl Fish Forensics: two strategies for fish identification Purpose: The purpose of this activity is to learn about two different strategies for identifying fish. One is using a dichotomous key based on physical characteristics and the second is DNA barcoding. We typically present this activity as a 10- to 15-minute exercise, but it can be easily modified to discuss the process of DNA barcoding more in depth, or to even perform these laboratory protocols. Please feel free to reach out to Ocean Genome Legacy if you have any questions or would like guidance about completing any protocols in a laboratory. Part 1: Why is it important to be identify fish? 1. Have each student, or pair of students, chose a fish. We often have students pretend they are ‘fishing’ when they select their fish. a. Fish images are in the “Fish” folder. 2. Discuss why it is important to know the identity of this fish. a. fisheries management b. food safety c. conservation d. others? Part 2: Learning to use a dichotomous key 1. One way to identify an organism is to use morphological features. Using the flow chart, answer each of the questions based on the image with which the student is working. a. Flow chart is DichotomousKeyFlow_10.11.17.pptx in the “Dichotomous Key” folder. b. The key is alternately displayed as a traditional dichotomous key with a series of questions. It can be found in the same folder. -

American Samoa's Alia Longline Fishery

AAmericanmerican Samoa’sSamoa’s AliaAlia LonglineLongline FisheryFishery PPaauull BBaarrttrraamm JJoohhnn KKaanneekkoo PPaaccMMaarr,, IInncc.. PaParrtt NNoo.. 11:: PrProofifillee HHiigghhlliinneerr AAlliiaa OOppeerraatitioonn,, 1100//0033-1-111//0044 CCrreeww aanndd CCoommmmuunniittyy AAuummaaggaa CCoolllleecctteedd DDaattaa GeGeaarr CoConnffiigguurraattiioonn ooff aa hhiigghhlliinneerr iinn tthhee AAmmeerriiccaann SSaammooaa ssmmaallll--ssccaallee ((aalliaa)) albbaaccoorre ffiisshheerryy bbeettweweeenn OcOctt.. 22000044 aanndd SSeepptt.. 22000044 MeMeaann lleennggtthh of Mainline (miles) 1100 MeMeaann nnuumbmbeerr ooff hhooookkss ppeerr set 441122 TTyyppee ooff hhooookkss 1144//00,, 1155//00 cciirrccllee TTyyppee ooff bbaaiitt ppiillcchhaarrddss ((ppiilliikkaakkii)) MeMeaann nnuumbmbeerr ooff hhooookkss bbeettwweeeenn 3311 ffllooaattss MeMeaann nnuumbmbeerr ooff lliigghhttstticks 00 NNuumbmbeerr ooff sseettss 115599 AAmmeerriiccaann SSaamomoaa ssmmaallll--ssccaallee ((aalliiaa)) aalbalbaccoorree ffiissheherryy bbeettwweeeenn OOcctt.. 22000044 aandnd SSeeptpt.. 22000044 AAlliiaa FFlleeeett CCoonnttrraacctteedd aalliiaa AAccttiivviittyy ((SSWW44)) NNuumbmbeerr ooff ttrriippss 553399 115599 NNuumbmbeerr ooff sseettss 662233 115599 NNuumbmbeerr ooff hhooookkss sseett 117700,,006655 6655,,443366 NNuumbmbeerr ooff lliigghhtt stiicckkss 330033 00 FFiisshhiinngg PPrraaccttiicceess ooff aa hhiigghhlliinneerr iinn tthhee AAmmeerriiccaann SSaammooaa ssmmaallll--ssccaallee ((aalliiaa)) aallbbaaccoorree ffiisshheerryy bbeettweweeenn OcOctt.. 22000033