Follow the Leader

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Language Arts 406 Fun with Fiction

Unit 6 | FUN WITH FICTION LANGUAGE ARTS 406 FUN WITH FICTION Introduction |3 1. Finding the Facts .......................................4 Book Reports |8 Handwriting and Spelling |14 Self Test 1 |20 2. Parables and Fables ..............................23 Parables and Fables |24 Following Directions |28 Handwriting and Spelling |29 Self Test 2 |34 3. Poetry ........................................................37 Poetry Review |38 Poetry Tips |40 Poetry Writing |43 Handwriting and Spelling |49 Self Test 3 |56 LIFEPAC Test |Pull-out | 1 FUN WITH FICTION | Unit 6 Author: Mildred Spires Jacobs, M.A. Editor-in-Chief: Richard W. Wheeler, M.A. Ed. Editor: Blair Ressler, M.A. Consulting Editor: Rudolph Moore, Ph.D. Revision Editor: Alan Christopherson, M.S. Media Credits: Page 3: © Photodisk, Thinkstock; 4: © vicnt, iStock, Thinkstock.jpg; 5: © Comstock Images, Stockbyte, Thinkstock 6: © Randimal, iStock, Thinkstock; 7: © Waldemarus, iStock, Thinkstock; 8: © ffooter, iStock, Thinkstock; 12: © jandrielombard, iStock, Thinkstock; 13: © pialhovik, iStock, Thinkstock; 18: © enisaksoy, iStock, Thinstock; 23: © egal, iStock, Thinkstock; 25: © Brian Guest, iStock, Thinkstock; 28: © GlobalP, iStock, Thinkstock 37: © alexaldo, iStock, Thinkstock; 42: © DejanKolar, iStock, Thinkstock; 45: © deyangeorgiev, iStock, Thinkstock; 47: © Bajena, iStock, Thinkstock. 804 N. 2nd Ave. E. Rock Rapids, IA 51246-1759 © MCMXCVI by Alpha Omega Publications, Inc. All rights reserved. LIFEPAC is a registered trademark of Alpha Omega Publications, Inc. All trademarks and/or service marks referenced in this material are the property of their respective owners. Alpha Omega Publications, Inc. makes no claim of ownership to any trademarks and/or service marks other than their own and their affiliates, and makes no claim of affiliation to any companies whose trademarks may be listed in this material, other than their own. -

FISH LIST WISH LIST: a Case for Updating the Canadian Government’S Guidance for Common Names on Seafood

FISH LIST WISH LIST: A case for updating the Canadian government’s guidance for common names on seafood Authors: Christina Callegari, Scott Wallace, Sarah Foster and Liane Arness ISBN: 978-1-988424-60-6 © SeaChoice November 2020 TABLE OF CONTENTS GLOSSARY . 3 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY . 4 Findings . 5 Recommendations . 6 INTRODUCTION . 7 APPROACH . 8 Identification of Canadian-caught species . 9 Data processing . 9 REPORT STRUCTURE . 10 SECTION A: COMMON AND OVERLAPPING NAMES . 10 Introduction . 10 Methodology . 10 Results . 11 Snapper/rockfish/Pacific snapper/rosefish/redfish . 12 Sole/flounder . 14 Shrimp/prawn . 15 Shark/dogfish . 15 Why it matters . 15 Recommendations . 16 SECTION B: CANADIAN-CAUGHT SPECIES OF HIGHEST CONCERN . 17 Introduction . 17 Methodology . 18 Results . 20 Commonly mislabelled species . 20 Species with sustainability concerns . 21 Species linked to human health concerns . 23 Species listed under the U .S . Seafood Import Monitoring Program . 25 Combined impact assessment . 26 Why it matters . 28 Recommendations . 28 SECTION C: MISSING SPECIES, MISSING ENGLISH AND FRENCH COMMON NAMES AND GENUS-LEVEL ENTRIES . 31 Introduction . 31 Missing species and outdated scientific names . 31 Scientific names without English or French CFIA common names . 32 Genus-level entries . 33 Why it matters . 34 Recommendations . 34 CONCLUSION . 35 REFERENCES . 36 APPENDIX . 39 Appendix A . 39 Appendix B . 39 FISH LIST WISH LIST: A case for updating the Canadian government’s guidance for common names on seafood 2 GLOSSARY The terms below are defined to aid in comprehension of this report. Common name — Although species are given a standard Scientific name — The taxonomic (Latin) name for a species. common name that is readily used by the scientific In nomenclature, every scientific name consists of two parts, community, industry has adopted other widely used names the genus and the specific epithet, which is used to identify for species sold in the marketplace. -

L'équipe Des Scénaristes De Lost Comme Un Auteur Pluriel Ou Quelques Propositions Méthodologiques Pour Analyser L'auctorialité Des Séries Télévisées

Lost in serial television authorship : l’équipe des scénaristes de Lost comme un auteur pluriel ou quelques propositions méthodologiques pour analyser l’auctorialité des séries télévisées Quentin Fischer To cite this version: Quentin Fischer. Lost in serial television authorship : l’équipe des scénaristes de Lost comme un auteur pluriel ou quelques propositions méthodologiques pour analyser l’auctorialité des séries télévisées. Sciences de l’Homme et Société. 2017. dumas-02368575 HAL Id: dumas-02368575 https://dumas.ccsd.cnrs.fr/dumas-02368575 Submitted on 18 Nov 2019 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. Distributed under a Creative Commons Attribution - NonCommercial - NoDerivatives| 4.0 International License UNIVERSITÉ RENNES 2 Master Recherche ELECTRA – CELLAM Lost in serial television authorship : L'équipe des scénaristes de Lost comme un auteur pluriel ou quelques propositions méthodologiques pour analyser l'auctorialité des séries télévisées Mémoire de Recherche Discipline : Littératures comparées Présenté et soutenu par Quentin FISCHER en septembre 2017 Directeurs de recherche : Jean Cléder et Charline Pluvinet 1 « Créer une série, c'est d'abord imaginer son histoire, se réunir avec des auteurs, la coucher sur le papier. Puis accepter de lâcher prise, de la laisser vivre une deuxième vie. -

NOTE on the Fishery and Some Aspects of the Biology of Dogtooth Tuna, Gymnosarda Unicolor (Ruppell)From Minicoy, Lakshadweep

I. mar. biol. Ass. India, 47 (1) : 111 - 113, Jan. - June, 2005 NOTE On the fishery and some aspects of the biology of dogtooth tuna, Gymnosarda unicolor (Ruppell)from Minicoy, Lakshadweep M.Sivadas and A.Anasukoya Research Centre of Central Marine Fisheries Research Institute, Calicut - 673 005, India Abstract The results of a study, on the fishery and biology of dogtooth tuna, Gymnosarda unicolor (Ruppell), conducted at Minicoy during 1995 to 1999 are presented. The resource is exploited from around the reef areas during July-August or September for sustenance when the usual fishing activities like pole and line and trolling are suspended. The total catch in a season varied from 56 to 481 kg. The size ranged from 44 to 126 cm fork length with the modal group at 58 and 62 cm. The length-weight relationship was found to be Log W = -4.5337 + 2.77 Log L. Fish below 70 cm size was found to be immature. The dogtooth tuna, Gymnosarda unicolor Material and methods (Ruppell) is a tropical Indo-Pacific epipe- Data on catch and biological aspects lagic species usually found around coral such as length, weight, feeding condition, reefs. In India, they are reported from maturity, etc were collected almost on a Andaman-Nicobar and from daily basis at the landing centre itself Lakshadweep Islands (Silas and Pillai, during each season. The entrails of the 1982). In Lakshadweep, they are not fishes are removed at the landing centre exploited by pole and line and troll line but are caught regularly, though in few itself before they are taken home. -

A Valuation of Tuna in the Eastern Pacific Ocean

A fact sheet from July 2016 Gerard Soury Netting Billions: A Valuation of Tuna in the Eastern Pacific Ocean Overview Together, the seven most commercially important tuna species are among the most economically valuable fish on the planet. Globally, commercially landed tuna product has a value of US$10 billion to $12 billion per year to the fishermen that target tunas and more than US$42 billion per year at the final point of sale. These conservative totals do not account for noncommercial values of tuna, including those associated with sport fishing, other forms of tourism, and the ecosystem benefits of living tunas. Figure 1 Value of Tuna in the Eastern Pacific by Species Though second to skipjack in landings, yellowfin lead the way in value for fishermen and at the final point of sale Landings (metric tons) 262,000 95,000 243,000 48,000 5,000 Dock value (USD) $0.3 billion $0.29 billion $0.33 billion $0.13 billion $0.063 billion End value (USD) $1.67 billion $2.4 billion $0.43 billion $0.99 billion $0.3 billion Skipjack Albacore Bigeye Yellowfin Pacific bluefin Note: Landings, dock value, and end value in 2014 of tuna caught in the IATTC Convention Area, based on data provided by fishing nations to the IATTC and a market analysis performed by Poseidon Aquatic Resource Management Ltd. Source: Graeme Macfadyen, Estimate of Global Sales Values From Tuna Fisheries—Phase 3 Report, Poseidon Aquatic Resource Management Ltd. (2016) © 2016 The Pew Charitable Trusts The Pacific Ocean is the source of about 70 percent of commercially landed tuna and 65 to 70 percent of the global value of tuna at both the dock and the final point of sale. -

Do Some Atlantic Bluefin Tuna Skip Spawning?

SCRS/2006/088 Col. Vol. Sci. Pap. ICCAT, 60(4): 1141-1153 (2007) DO SOME ATLANTIC BLUEFIN TUNA SKIP SPAWNING? David H. Secor1 SUMMARY During the spawning season for Atlantic bluefin tuna, some adults occur outside known spawning centers, suggesting either unknown spawning regions, or fundamental errors in our current understanding of bluefin tuna reproductive schedules. Based upon recent scientific perspectives, skipped spawning (delayed maturation and non-annual spawning) is possibly prevalent in moderately long-lived marine species like bluefin tuna. In principle, skipped spawning represents a trade-off between current and future reproduction. By foregoing reproduction, an individual can incur survival and growth benefits that accrue in deferred reproduction. Across a range of species, skipped reproduction was positively correlated with longevity, but for non-sturgeon species, adults spawned at intervals at least once every two years. A range of types of skipped spawning (constant, younger, older, event skipping; and delays in first maturation) was modeled for the western Atlantic bluefin tuna population to test for their effects on the egg-production-per-recruit biological reference point (stipulated at 20% and 40%). With the exception of extreme delays in maturation, skipped spawning had relatively small effect in depressing fishing mortality (F) threshold values. This was particularly true in comparison to scenarios of a juvenile fishery (ages 4-7), which substantially depressed threshold F values. Indeed, recent F estimates for 1990-2002 western Atlantic bluefin tuna stock assessments were in excess of threshold F values when juvenile size classes were exploited. If western bluefin tuna are currently maturing at an older age than is currently assessed (i.e., 10 v. -

India's National Report to the Scientific Committee of the Indian Ocean

IOTC–2015–SC18–NR09[E] India’s National Report to the Scientific Committee of the Indian Ocean Tuna Commission’2015 Premchand, L. Ramalingam, A. Tiburtius, A. Siva, Ansuman Das, Rajashree B Sanadi and Rahul Kumar B Tailor Fishery Survey of India Government of India, Botawala Chambers, Sir. P. M. Road, Mumbai 0 INFORMATION OF FISHERIES, RESEARCH AND STATISTICS In accordance with IOTC Resolution 15/02, final YES scientific data for the previous year was Communication F.No.43-6/2014 Fy. II, dated provided to the Secretariat by June of the 03/07/2015 to the Ministry of Agriculture and current year, for all fleets other than Farmer’s Welfare, New Delhi. longline(e.g., for a National report submitted to the Secretariat in 2015, final data for the 2014 Calendar year must be provided to the Secretariat by 30 June’2015) In accordance with IOTC Resolution 15/02, YES provisional longline data for the previous year Communication F.No.43-6/2014 Fy.II, was provided to the Secretariat by 30 June of 03/07/2015 to the Ministry of Agriculture and the current year (e.g., for a National report Farmer’s Welfare, New Delhi. submitted to the Secretariat in 2015, final data for the 2014 Calendar year must be provided to the Secretariat by 30 June’2015) Reminder: Final longline data for the previous year is due to the Secretariat by 30 December of the current year (e.g., for a National report submitted to the Secretariat in 2015, final data for the 2014 Calendar year must be provided to the Secretariat by 30 June’2015) If no, please indicate the reason(s) and intended actions: - Executive Summary Tuna and tuna like fishes are one of the components of pelagic resources. -

NOAA's Description of the U.S Commercial Fisheries Including The

6.0 DESCRIPTION OF THE PELAGIC LONGLINE FISHERY FOR ATLANTIC HMS The HMS FMP provides a thorough description of the U.S. fisheries for Atlantic HMS, including sectors of the pelagic longline fishery. Below is specific information regarding the catch of pelagic longline fishermen in the Gulf of Mexico and off the Southeast coast of the United States. For more detailed information on the fishery, please refer to the HMS FMP. 6.1 Pelagic Longline Gear The U.S. pelagic longline fishery for Atlantic HMS primarily targets swordfish, yellowfin tuna, or bigeye tuna in various areas and seasons. Secondary target species include dolphin, albacore tuna, pelagic sharks including mako, thresher, and porbeagle sharks, as well as several species of large coastal sharks. Although this gear can be modified (i.e., depth of set, hook type, etc.) to target either swordfish, tunas, or sharks, like other hook and line fisheries, it is a multispecies fishery. These fisheries are opportunistic, switching gear style and making subtle changes to the fishing configuration to target the best available economic opportunity of each individual trip. Longline gear sometimes attracts and hooks non-target finfish with no commercial value, as well as species that cannot be retained by commercial fishermen, such as billfish. Pelagic longline gear is composed of several parts. See Figure 6.1. Figure 6.1. Typical U.S. pelagic longline gear. Source: Arocha, 1997. When targeting swordfish, the lines generally are deployed at sunset and hauled in at sunrise to take advantage of the nocturnal near-surface feeding habits of swordfish. In general, longlines targeting tunas are set in the morning, deeper in the water column, and hauled in the evening. -

TUNA FISHERY in KENY a Prepared by Dorcus Sigana National Component 4

IOTC-2009-SC-INF09 TUNA FISHERY IN KENY A prepared by Dorcus Sigana National Component 4 In Kenya, Tuna fishery is carried out artisanally and industrially. Artisanal fishermen sell their catch to the domestic market while Industrial fishermen process and export to the European Union market. Fishing is mainly confined to the coastal waters up to 50 meters depth. At Ungwana Bay, fishing has been extended to groups up to 200 meters for deep- water lobsters, prawns and demersal fishes. The larger pelagic fishes comprise the tuna and tuna-like species and the larger carangids, which are caught in large numbers between 15–200 meters depth mostly in June and July. Surveys on marine fisheries resources of Kenya dates back from 1951 when the East African Marine Fisheries Research Organization was formed, during which time the emphasis was on pelagic species. During the surveys on pelagic fishes between 1951 and 1954 catches of 0.52 kg/line/hr were obtained. 22% of the total catch was Scomberomorus commerson (Williams, 1956). In the same survey it was observed that tunas, especially the yellow fin tuna Thunnus albacares was present throughout the year, but with marked increase during the Southeast monsoon and very close to the shore up to 4 km off-shore. Other tunas that were found in the area were Albacare Thunnus alalunga, the dogtooth tuna Gymnosarda unicolor, small tuna Euthynnus affinis and skipjack Katsuwonus pelamis. Although these species were found within the Kenya waters they are unexploited. The Norad report states that Tunas are unique among fishes in having limited thermo- regulatory capacity. -

IATTC-94-01 the Tuna Fishery, Stocks, and Ecosystem in the Eastern

INTER-AMERICAN TROPICAL TUNA COMMISSION 94TH MEETING Bilbao, Spain 22-26 July 2019 DOCUMENT IATTC-94-01 REPORT ON THE TUNA FISHERY, STOCKS, AND ECOSYSTEM IN THE EASTERN PACIFIC OCEAN IN 2018 A. The fishery for tunas and billfishes in the eastern Pacific Ocean ....................................................... 3 B. Yellowfin tuna ................................................................................................................................... 50 C. Skipjack tuna ..................................................................................................................................... 58 D. Bigeye tuna ........................................................................................................................................ 64 E. Pacific bluefin tuna ............................................................................................................................ 72 F. Albacore tuna .................................................................................................................................... 76 G. Swordfish ........................................................................................................................................... 82 H. Blue marlin ........................................................................................................................................ 85 I. Striped marlin .................................................................................................................................... 86 J. Sailfish -

Atlantic Bluefin Tuna

QUALITY STATUS REPORT 2010 Case Reports for the OSPAR List of threatened and/or declining species and habitats – Update Nomination and biomass of older fish since 1993. The reported catch for the East Atlantic and Atlantic bluefin tuna Mediterranean stocks in 2000 was 33,754 MT, Thunnus thynnus about 60% of the peak catch in 1996 although this is probably an under-estimate because of increasing uncertainty about catch statistics (ICCAT, 2002). The best current determination of the state of the stock is that the Spawning Stock Biomass is 86% of the 1970 level. This is similar to the results obtained in 1998 in terms of trends, but more optimistic in terms of current depletion. Nevertheless, the International Commission for the Conservation of Atlantic Tunas (ICCAT) Geographical extent considers that current catch levels are not OSPAR Regions: V sustainable in the long-term (ICCAT, 2002). Biogeographic zones:1,2,4-8 Region & Biogeographic zones specified for Sensitivity decline and/or threat: as above The Atlantic bluefin tuna has a slow growth rate, long life span (up to 20 years) and late The Atlantic bluefin tuna is an oceanic species age of maturity for a fish (4-5 years for the that comes close to shore on a seasonal basis. eastern stock) resulting in a large number of Current management regimes work on the juvenile classes. These characteristics make it basis of their being two stocks, an Eastern more vulnerable to fishing pressure than Atlantic and a Western Atlantic stock, although rapidly growing tropical tuna species (ICCAT, some intermingling is thought to occur along 2002). -

Among the World's Most Popular Game Fishes, Tunas Are Also

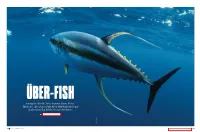

ÜBER-FISH Among the World’s Most Popular Game Fishes, Tunas Are Also Some of the Most Highly Evolved and Sophisticated of All the Ocean’s Predators BY DOUG OLANDER DANIEL GOEZ DANIEL 74 DECEMBER 2017 SPORTFISHINGMAG.COM 75 The Family Tree minimizes drag with a very low reduce the turbulence in the Tunas are part of the family drag coefficient,” optimizing effi- water ahead of the tail. Scombridae, which also includes cient swimming both at cruise Unlike most fishes with broad, mackerels, large and small. But and burst. While most fishes bend flexible tails that bend to scoop there are tunas, and then there their bodies side to side when water to move a fish forward, are, well, “true tunas.” moving forward, tunas’ bodies tunas derive tremendous That is, two groups don’t bend. They’re essentially thrust with thin, hard, lunate WHILE MOST FISHES BEND ( sometimes known as “tribes”) rigid, solid torpedoes. ( crescent-moon-shaped) tails dominate the tuna clan. One is And these torpedoes are that beat constantly, capable of THEIR BODIES SIDE TO SIDE Thunnini, which is the group perfectly streamlined, their 10 to 12 or more beats per second. considered true tunas, charac- larger fins fitting perfectly into That relentless thrust accounts WHEN MOVING FORWARD, terized by two separate dorsal grooves so no part of these fins for the unstoppable runs that fins and a relatively thick body. a number of highly specialized protrudes above the body surface. tuna make repeatedly when TUNAS’ BODIES DON’T BEND. The 15 species of Thunnini are features facilitate these They lack the convex eyes of hooked.