Performance Media Industries, Ltd

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Shadow Telecinetelecine

ShadowShadow TelecineTelecine HighHigh performanceperformance SolidSolid StateState DigitalDigital FilmFilm ImagingImaging TechnologyTechnology Table of contents • Introduction • Simplicity • New Scanner Design • All Digital Platform • The Film Look • Graphical Control Panel • Film Handling • Main Features • Six Sector Color Processor • Cost of ownership • Summary SHADOWSHADOTelecine W Telecine Introduction The Film Transfer market is changing const- lantly. There are a host of new DTV formats required for the North American Market and a growing trend towards data scanning as opposed to video transfer for high end compositing work. Most content today will see some form of downstream compression, so quiet, stable images are still of paramount importance. With the demand growing there is a requirement for a reliable, cost effective solution to address these applications. The Shadow Telecine uses the signal proce- sing concept of the Spirit DataCine and leve- rages technology and feature of this flagship product. This is combined with a CCD scan- ner witch fulfils the requirements for both economical as well as picture fidelity. The The Film Transfer market is evolving rapidly. There are a result is a very high performance producthost allof new DTV formats required for the North American the features required for today’s digital Marketappli- and a growing trend towards data scanning as cation but at a greatly reduced cost. opposed to video transfer for high end compositing work. Most content today will see some form of downstream Unlike other Telecine solutions availablecompression, in so quiet, stable images are still of paramount importance. With the demand growing there is a this class, the Shadow Telecine is requirementnot a for a reliable, cost effective solution to re-manufactured older analog Telecine,address nor these applications. -

Problems on Video Coding

Problems on Video Coding Guan-Ju Peng Graduate Institute of Electronics Engineering, National Taiwan University 1 Problem 1 How to display digital video designed for TV industry on a computer screen with best quality? .. Hint: computer display is 4:3, 1280x1024, 72 Hz, pro- gressive. Supposing the digital TV display is 4:3 640x480, 30Hz, Interlaced. The problem becomes how to convert the video signal from 4:3 640x480, 60Hz, Interlaced to 4:3, 1280x1024, 72 Hz, progressive. First, we convert the video stream from interlaced video to progressive signal by a suitable de-interlacing algorithm. Thus, we introduce the de-interlacing algorithms ¯rst in the following. 1.1 De-Interlacing Generally speaking, there are three kinds of methods to perform de-interlacing. 1.1.1 Field Combination Deinterlacing ² Weaving is done by adding consecutive ¯elds together. This is ¯ne when the image hasn't changed between ¯elds, but any change will result in artifacts known as "combing", when the pixels in one frame do not line up with the pixels in the other, forming a jagged edge. This technique retains full vertical resolution at the expense of half the temporal resolution. ² Blending is done by blending, or averaging consecutive ¯elds to be displayed as one frame. Combing is avoided because both of the images are on top of each other. This instead leaves an artifact known as ghosting. The image loses vertical resolution and 1 temporal resolution. This is often combined with a vertical resize so that the output has no numerical loss in vertical resolution. The problem with this is that there is a quality loss, because the image has been downsized then upsized. -

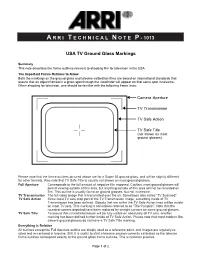

A R R I T E C H N I C a L N O T E

A R R I T E C H N I C A L N O T E P - 1013 USA TV Ground Glass Markings Summary This note describes the frame outlines relevant to shooting film for television in the USA. The Important Frame Outlines to Know Both the markings on the ground glass and telecine calibration films are based on international standards that assure that an object framed in a given spot through the viewfinder will appear on that same spot in telecine. When shooting for television, one should be familiar with the following frame lines: Camera Aperture TV Transmission TV Safe Action TV Safe Title (not shown on most ground glasses) Please note that the frame outlines pictured above are for a Super 35 ground glass, and will be slightly different for other formats. Also note that TV Safe Title is usually not shown on most ground glasses. Full Aperture Corresponds to the full amount of negative film exposed. Caution: most ground glasses will permit viewing outside of this area, but anything outside of this area will not be recorded on film. This outline is usually found on ground glasses, but not in telecine. TV Transmission The full video image that is transmitted over the air. Sometimes also called “TV Scanned”. TV Safe Action Since most TV sets crop part of the TV Transmission image, a marking inside of TV Transmission has been defined. Objects that are within the TV Safe Action lines will be visible on most TV sets. This marking is sometimes referred to as “The Pumpkin”. -

Spirit 4K® High-Performance Film Scanner with Bones and Datacine®

Product Data Sheet Spirit 4K® High-Performance Film Scanner with Bones and DataCine® Spirit 4K Film Scanner/Bones Combination Digital intermediate production – the motion picture workflow in which film is handled only once for scan- ning and then processed with a high-resolution digital clone that can be down-sampled to the appropriate out- put resolution – demands the highest resolution and the highest precision scanning. While 2K resolution is widely accepted for digital post production, there are situations when even a higher re- solution is required, such as for digital effects. As the cost of storage continues to fall and ultra-high resolu- tion display devices are introduced, 4K postproduction workflows are becoming viable and affordable. The combination of the Spirit 4K high-performance film scanner and Bones system is ahead of its time, offe- ring you the choice of 2K scanning in real time (up to 30 frames per second) and 4K scanning at up to 7.5 fps depending on the selected packing format and the receiving system’s capability. In addition, the internal spatial processor of the Spirit 4K system lets you scan in 4K and output in 2K. This oversampling mode eli- minates picture artifacts and captures the full dynamic range of film with 16-bit signal processing. And in either The Spirit 4K® from DFT Digital Film Technology is 2K or 4K scanning modes, the Spirit 4K scanner offers a high-performance, high-speed Film Scanner and unrivalled image detail, capturing that indefinable film DataCine® solution for Digital Intermediate, Commer- look to perfection. cial, Telecine, Restoration, and Archiving applications. -

185 for Presentation July 8, 1971, NATIONAL CABLE TELEVISION

185 For presentation July 8, 1971, NATIONAL CABLE TELEVISION ASSOCIATION, Washington, D. C. TELECINE SYSTEMS FOR THE CATV ORIGINATION CENTER by Kenneth K. Kaylor Phil ips Broadcast Equipment Corp. Although 11 1 ive'' programming is considered a necessary part of the program origination services of a community-oriented CATV system, tele- cine facilities will hold the key to success or failure of such an operation from an economic standpoint. The word 11 tele-cine11 was developed during the early days of television broadcasting to define those facil i- ties devoted to the video reproduction of the various film media. Since the original commercial telecine television camera was an 11 iconoscope11 camera which had a very large sensitive surface (about 11 11 3 x 4 ), a film projector was focused onto the sensor by using a standard projection lens as shown in Fig. 1. This technique was quite simple and optical alignment was very easy. E1 im i nat i ng the 11 Shutte r Bar" effect In the case of motion picture film, the theatre projector had to be modified in order to prevent a "shutter bar" effect caused by the 186 difference in frame rates between television and motion picture stan dards. Standard sound motion picture film operates at 24 frames per second while the U. S. standard for television scanning is 30 frames per second. The intermittent mechanism had to be modified so that the 1ength of time between "pu 11 -downs" a 1 te rnates between 1/20 and 1/30 second. The average of these two fractions is 1/24 second, or the time demanded by the standard 24-frame-per-second motion picture projection rate. -

EBU Tech 3315-2006 Archiving: Experiences with TK Transfer to Digital

EBU – TECH 3315 Archiving: Experiences with telecine transfer of film to digital formats Source: P/HDTP Status: Report Geneva April 2006 1 Page intentionally left blank. This document is paginated for recto-verso printing Tech 3315 Archiving: Experiences with telecine transfer of film to digital formats Contents Introduction ......................................................................................................... 5 Decisions on Scanning Format .................................................................................... 5 Scanning tests ....................................................................................................... 6 The Results .......................................................................................................... 7 Observations of the influence of elements of film by specialists ........................................ 7 Observations on the results of the formal evaluations .................................................... 7 Overall conclusions .............................................................................................. 7 APPENDIX : Details of the Tests and Results ................................................................... 9 3 Archiving: Experiences with telecine transfer of film to digital formats Tech 3315 Page intentionally left blank. This document is paginated for recto-verso printing 4 Tech 3315 Archiving: Experiences with telecine transfer of film to digital formats Archiving: Experience with telecine transfer of film to digital formats -

Curriculum Vitae

Curriculum Vitae Morgan Rengasamy 10 Strickland Avenue Lindfield, Sydney, NSW 2070 Australia [email protected] +61 (02) 98807705 - Home +61 (0) 401 080 400 -mobile Objective Utilising the invaluable skill sets gained to push the boundaries of what is achievable in the realms of Colour correction, working as a team player in a dynamic, and creatively stimulating, post -production company. Personal Details: British Citizen D.O.B. 13 July 1958 Status: Married Four Sons and one Daughter Work History: Worked In the Film & Video industry since 1985 Colourist since 1991.Experience of a broad spectrum of film Scanners ranging from, Cintel’s Jumpscan telecine, Mk3, through to the Rascal Digital, plus Philips Spirit Datacine. Grading systems: Davinci, Pandora, Filmlight. Present: Freelance Colourist/ Consultant Previous: 09/2000 to 09/2003 Seoulvisions Postproduction. Seoul, Korea. Head of Telecine Department Rank Cintel Rascal Digital & DaVinci 2K plus 09/1997 to 09/2000 Omnicon Postproduction Pty ltd. Senior Colourist Sydney Australia. URSA Diamond & Davinci 07/96 to 09/97 Freelance Durran, Paris. Freelance Colourist Rank Mk3 & DaVinci Work History continued: Film Teknic, Norway. Consultant / Trainer URSA Gold, & Davinci Fritihof Film to Video, Stockholm Freelance Colourist URSA Gold & Davinci The House postproduction, London Freelance Colourist URSA Diamond & DaVinci La truka, Spain Trainer / Demonstrator Spirit & DaVinci Fame postproduction Thailand Freelance Colourist / Consultant URSA Diamond & DaVinci 07/95 to 07/96 The House postproduction London Head of Telecine URSA Diamond & DaVinci 04/94 to 07/95 Rushes postproduction, London Senior Colourist URSA Gold/ DaVinci 04/89 to 04/94 SVC Postproduction, London Edit assist / Colourist Jump scan, Rank Mk3, URSA & DaVinci 08/86 to 04/89 Rank Video Duplication Tape operator Professional Martial Arts instructor Barista Variety of Work: Commercials, music Videos, & Long form. -

TELEVISION and VIDEO PRESERVATION 1997: a Report on the Current State of American Television and Video Preservation Volume 1

ISBN: 0-8444-0946-4 [Note: This is a PDF version of the report, converted from an ASCII text version. It lacks footnote text and some of the tables. For more information, please contact Steve Leggett via email at "[email protected]"] TELEVISION AND VIDEO PRESERVATION 1997 A Report on the Current State of American Television and Video Preservation Volume 1 October 1997 REPORT OF THE LIBRARIAN OF CONGRESS TELEVISION AND VIDEO PRESERVATION 1997 A Report on the Current State of American Television and Video Preservation Volume 1: Report Library of Congress Washington, D.C. October 1997 Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Television and video preservation 1997: A report on the current state of American television and video preservation: report of the Librarian of Congress. p. cm. þThis report was written by William T. Murphy, assigned to the Library of Congress under an inter-agency agreement with the National Archives and Records Administration, effective October 1, 1995 to November 15, 1996"--T.p. verso. þSeptember 1997." Contents: v. 1. Report - ISBN 0-8444-0946-4 1. Television film--Preservation--United States. 2. Video tapes--Preservation--United States. I. Murphy, William Thomas II. Library of Congress. TR886.3 .T45 1997 778.59'7'0973--dc 21 97-31530 CIP Table of Contents List of Figures . Acknowledgements. Preface by James H. Billington, The Librarian of Congress . Executive Summary . 1. Introduction A. Origins of Study . B. Scope of Study . C. Fact-finding Process . D. Urgency. E. Earlier Efforts to Preserve Television . F. Major Issues . 2. The Materials and Their Preservation Needs A. -

Alchemist File - Understanding Cadence

GV File Understanding Cadence Alchemist File - Understanding Cadence Version History Date Version Release by Reason for changes 27/08/2015 1.0 J Metcalf Document originated (1st proposal) 09/09/2015 1.1 J Metcalf Rebranding to Alchemist File 19/01/2016 1.2 G Emerson Completion of rebrand 07/10/2016 1.3 J Metcalf Updated for additional cadence controls added in V2.2.3.2 12/10/2016 1.4 J Metcalf Added Table of Terminology 11/12/2018 1.5 J Metcalf Rebrand for GV and update for V4.*** 16/07/2019 1.6 J Metcalf Minor additions & corrections 05/03/2021 1.7 J Metcalf Rebrand 06/09/2021 1.8 J Metcalf Add User Case (case 9) Version Number: 1.8 © 2021 GV Page 2 of 53 Alchemist File - Understanding Cadence Table of Contents 1. Introduction ............................................................................................................................................... 6 2. Alchemist File Input Cadence controls ................................................................................................... 7 2.1 Input / Source Scan - Scan Type: ............................................................................................................ 7 2.1.1 Incorrect Metadata ............................................................................................................................ 8 2.1.2 Psf Video sources ............................................................................................................................. 9 2.2 Input / Source Scan - Field order .......................................................................................................... -

Video Processor, Video Upconversion & Signal Switching

81LumagenReprint 3/1/04 1:01 PM Page 1 Equipment Review Lumagen VisionPro™ Video Processor, Video Upconversion & Signal Switching G REG R OGERS Lumagen VisionPro™ Reviewer’s Choice The Lumagen VisionPro™ Video Processor is the type of product that I like to review. First and foremost, it delivers excep- tional performance. Second, it’s an out- standing value. It provides extremely flexi- ble scaling functions and valuable input switching that isn’t included on more expen- sive processors. Third, it works as adver- tised, without frustrating bugs or design errors that compromise video quality or ren- Specifications: der important features inoperable. Inputs: Eight Programmable Inputs (BNC); Composite (Up To 8), S-Video (Up To 8), Manufactured In The U.S.A. By: Component (Up To 4), Pass-Through (Up To 2), “...blends outstanding picture SDI (Optional) Lumagen, Inc. Outputs: YPbPr/RGB (BNC) 15075 SW Koll Parkway, Suite A quality with extremely Video Processing: 3:2 & 2:2 Pulldown Beaverton, Oregon 97006 Reconstruction, Per-Pixel Motion-Adaptive Video Tel: 866 888 3330 flexible scaling functions...” Deinterlacing, Detail-Enhancing Resolution www.lumagen.com Scaling Output Resolutions: 480p To 1080p In Scan Line Product Overview Increments, Plus 1080i Dimensions (WHD Inches): 17 x 3-1/2 x 10-1/4 Price: $1,895; SDI Input Option, $400 The VisionPro ($1,895) provides two important video functions—upconversion and source switching. The versatile video processing algorithms deliver extensive more to upconversion than scaling. Analog rithms to enhance edge sharpness while control over input and output formats. Video source signals must be digitized, and stan- virtually eliminating edge-outlining artifacts. -

Area of 35 Mm Motion Picture Film Used in HDTV Telecines

Rec. ITU-R BR.716-2 1 RECOMMENDATION ITU-R BR.716-2* AREA OF 35 mm MOTION PICTURE FILM USED BY HDTV TELECINES (Question ITU-R 113/11) (1990-1992-1994) Rec. ITU-R BR.716-2 The ITU Radiocommunication Assembly, considering a) that telecines are sometimes used as a television post-production tool for special applications such as the scanning of negative film or other image processing operations, and it is necessary to be able to position the scanned area anywhere on the film exposed area for this application; b) that telecines are also used to televise film programmes with no image post-processing, and it is desirable that the area to be used on the film frame be specified for this application; c) that many formats exist for 35 mm feature films, as listed below, and preferred dimensions for the area used on the frames of all those formats should be recommended: – 1.37:1 (“Academy” format, close to 4:3) – 1.66:1 (European wide-screen format, close to 16:9) – 1.85:1 (United States wide-screen format, close to 16:9) – 2.35:1 (anamorphic “Cinemascope” format); d) the content of ISO Standard 2906 “Image area produced by camera aperture on 35 mm motion picture film”, and that of ISO Standard 2907 “Maximum projectable image area on 35 mm motion picture film” which specifies the dimensions of the projectable area for all the frame formats listed above; e) the content of Recommendation ITU-R BR.713 “Recording of HDTV images on film”, which is based on ISO Standards 2906 and 2907, recommends 1. -

FOR SALE 1X Used Philips Spirit HD SDC 2000 Data Cine Film Scanner

FOR SALE 1x used Philips Spirit HD SDC 2000 Data Cine Film Scanner HD Option for 1080i and 1080p included Wetgate Option included Colour Correction Davinci 2K Plus included Dry Gates: 1x Kodak Full Aperture 35mm Lens Gate 1x Kodak Super 16mm Lens Gate STVMD Wet Gates: 1x Kodak Aperture 35mm Lens Gate 1x Kodak Super 16mm Lens Gate Colour correction: Davinci 2K Plus (Mainframe, IBM-GUI-PC, Gallery-PC and 3x 2K Plus Panel) Aaton Keycode Reader included Many more spare parts available – description below! One TV Store Board does not work at the moment – it is possible to repair it on request For sale: 1x used Philips Spirit HD SDC 2000 Data Cine Film Scanner Price on request: Excl. VAT Excl. shipping & insurance costs Excl. custom fees Workflow Spirit Data Cine: Spirit DataCine is a telecine and/or a motion picture film scanner. This device is able to transfer 16mm and 35mm motion picture film to NTSC or PAL television standards or one of many High-definition television standards. With the data transfer option a Spirit DataCine can STVMDoutput DPX data files. The image pick up device is a solid state charge-coupled device. This eliminated the need for glass vacuum tube CRTs used on older telecines. The units can transfer negative film, primetime, intermediate film and print film, stock. With a sound pick up option, optical 16mm and 35mm sound can be reproduced, also 16mm magnetic strip sound. The unit can operate stand alone or be controlled by a scene by scene colour corrector. The operator of the unit is called a Colourist or Colourist Assistant.