Rowing Hard in the Himalayas

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Impact of Climatic Change on Agro-Ecological Zones of the Suru-Zanskar Valley, Ladakh (Jammu and Kashmir), India

Journal of Ecology and the Natural Environment Vol. 3(13), pp. 424-440, 12 November, 2011 Available online at http://www.academicjournals.org/JENE ISSN 2006 - 9847©2011 Academic Journals Full Length Research Paper Impact of climatic change on agro-ecological zones of the Suru-Zanskar valley, Ladakh (Jammu and Kashmir), India R. K. Raina and M. N. Koul* Department of Geography, University of Jammu, India. Accepted 29 September, 2011 An attempt was made to divide the Suru-Zanskar Valley of Ladakh division into agro-ecological zones in order to have an understanding of the cropping system that may be suitably adopted in such a high altitude region. For delineation of the Suru-Zanskar valley into agro-ecological zones bio-physical attributes of land such as elevation, climate, moisture adequacy index, soil texture, soil temperature, soil water holding capacity, slope, vegetation and agricultural productivity have been taken into consideration. The agricultural productivity of the valley has been worked out according to Bhatia’s (1967) productivity method and moisture adequacy index has been estimated on the basis of Subrmmanyam’s (1963) model. The land use zone map has been superimposed on moisture adequacy index, soil texture and soil temperature, soil water holding capacity, slope, vegetation and agricultural productivity zones to carve out different agro-ecological boundaries. The five agro-ecological zones were obtained. Key words: Agro-ecology, Suru-Zanskar, climatic water balance, moisture index. INTRODUCTION Mountain ecosystems of the world in general and India in degree of biodiversity in the mountains. particular face a grim reality of geopolitical, biophysical Inaccessibility, fragility, diversity, niche and human and socio economic marginality. -

General Awareness Capsule for AFCAT II 2021 14 Points of Jinnah (March 9, 1929) Phase “II” of CDM

General Awareness Capsule for AFCAT II 2021 1 www.teachersadda.com | www.sscadda.com | www.careerpower.in | Adda247 App General Awareness Capsule for AFCAT II 2021 Contents General Awareness Capsule for AFCAT II 2021 Exam ............................................................................ 3 Indian Polity for AFCAT II 2021 Exam .................................................................................................. 3 Indian Economy for AFCAT II 2021 Exam ........................................................................................... 22 Geography for AFCAT II 2021 Exam .................................................................................................. 23 Ancient History for AFCAT II 2021 Exam ............................................................................................ 41 Medieval History for AFCAT II 2021 Exam .......................................................................................... 48 Modern History for AFCAT II 2021 Exam ............................................................................................ 58 Physics for AFCAT II 2021 Exam .........................................................................................................73 Chemistry for AFCAT II 2021 Exam.................................................................................................... 91 Biology for AFCAT II 2021 Exam ....................................................................................................... 98 Static GK for IAF AFCAT II 2021 ...................................................................................................... -

Use of Geo-Informatics for Combating Desertification in Stod Valley (1F4c2), Padam (Zanskar), District Kargil, J & K State

USE OF GEO-INFORMATICS FOR COMBATING DESERTIFICATION IN STOD VALLEY (1F4C2), PADAM (ZANSKAR), DISTRICT KARGIL, J & K STATE M.N. Koul1, R.K. Ganjoo2*, P.S.Dhinwa3, S.K.Pathan3 and Ajai3 1 Department of Geography, University of Jammu, Jammu 180 006, India 2 Department of Geology, University of Jammu, Jammu 180 006, India ([email protected]) 3 Space Application Centre, Ahmedabad 380 015, India KEY WORDS : ABSTRACT The paper deals with the desertification status mapping of Stod valley of Zanskar region, District Kargil, Jammu & Kashmir State (India), located in the altitudinal belt of 3450m to 6200m asl. The valley, located in the rain shadow region of Tethys Himalaya, is studded by eight major glaciers and witnesses permafrost condition for nearly six months. The valley experiences semi-arid to arid type of cold climate designated as Bc. The temperature in the valley fluctuates between -480C to -200C in winters at different altitude levels. The permafrost conditions lead to solifluctuation and gelifluction process producing immature soils and triggering the natural geomorphic hazards, such as snow and rock avalanches, landslides, and fluvio-glacial erosion. The hazards have been largely responsible in the generation of mass movement and other catastrophic activities that result in high morpho-dynamic activity of weathering, breaking of ice, and damming and bursting of lakes causing the desertification of the region. Various thematic maps, such as maps of geomorphological features, soils, slope, drainage, and meteorology on the sacle of 1:50,000 on the basis of IRS data supplemented by field work. Besides, collateral data from Indian Meteorology Department, J & K State Revenue Department, J & K State Desert Development Authority and other state government agencies and NGOs have been consulted to authenticate the thematic maps. -

Jr. Statistical Assistant

101 B QUESTION BOOKLET Q.B. Number: 101 Jr. Statistical Assistant INSTRUCTIONS Roll Number: Q.B. Series: B Please read the following instructions carefully. 9) For each answer as shown in the example below. The CORRECT and the WRONG method of darkening the 1) Mark carefully your Roll Number, Question Booklet CIRCLE on the OMR sheet are given below. Number and series of the paper on the OMR Answer Sheet and sign at the appropriate place. Write your Roll number Correct Method Wrong Method on the question booklet. 2) Strictly follow the instructions given by the Centre Supervisor / Room invigilator and those given on the Question Booklet. Please ensure you fill all the required details and shade the bubbles correctly on the OMR 10) In view of the tight time span, do not waste your time on Answer Sheet. a question which you find to be difficult. Go on solving questions one by one and come back to the difficult 3) Please mark the right responses ONLY with Blue/Black questions at the end. ball point pen. USE OF PENCIL AND GEL-PEN IS NOT ALLOWED. 11) DO NOT make any stray marks anywhere on the OMR Answer Sheet. DO NOT fold or wrinkle the OMR Answer 4) Candidates are not allowed to carry any papers, notes, Sheet. Rough work MUST NOT be done on the answer books, calculators, cellular phones, scanning devices, sheet. Use your question booklet for this purpose. pagers etc. to the Examination Hall. Any candidate found using, or in possession of such unauthorized material, indulging in copying or impersonation or adopting unfair means, is liable to be summarily disqualified and may be subjected to penal action. -

Sakthy Academy Coimbatore

Sakthy Academy Coimbatore DAMS IN INDIA Dams In India Name of Dam State River Nizam Sagar Dam Telangana Manjira River Somasila Dam Andhra Pradesh Pennar River Srisailam Dam Andhra Pradesh Krishna River Singur dam Telangana Manjira River Ukai Dam Gujarat Tapti River Dharoi Dam Gujarat Sabarmati River Kadana dam Gujarat Mahi River Dantiwada Dam Gujarat Banas River Pandoh Dam Himachal Pradesh Beas River Bhakra Nangal Dam Himachal Pradesh and Punjab Border Sutlej River Nathpa Jhakri Dam Himachal Pradesh Satluj River Chamera Dam Himachal Pradesh Ravi River Baglihar Dam Jammu and Kashmir Chenab River Dumkhar Hydroelectric Jammu and Kashmir Indus River Dam Uri Hydroelectric Dam Jammu and Kashmir Jhelum River Maithon Dam Jharkhand Barakar River Chandil Dam Jharkhand Swarnarekha River Panchet Dam Jharkhand Damodar River Tunga Bhadra Dam Karnataka Tungabhadra River Linganamakki dam Karnataka Sharavathi River Kadra Dam Karnataka Kalinadi River Alamatti Dam Karnataka Krishna River Supa Dam Karnataka Kalinadi or Kali river Krishna Raja Sagara Dam Karnataka Kaveri River www.sakthyacademy.com Hopes bus stop, Peelamedu, Coimbatore-04 82200 00624 / 82200 00625 Sakthy Academy Coimbatore Dams In India Harangi Dam Karnataka Harangi River Narayanpur Dam Karnataka Krishna River Kodasalli Dam Karnataka Kali River Malampuzha Dam Kerala Malampuzha River Peechi Dam Kerala Manali River Idukki Dam Kerala Periyar River Kundala Dam Kerala Kundala Lake Parambikulam Dam Kerala Parambikulam River Walayar Dam Kerala Walayar River Mullaperiyar Dam Kerala Periyar River -

Rock Art of Jammu and Kashmir

Rock Art of Jammu and Kashmir Dr. B. L. Malla Indira Gandhi National Centre for the Arts New Delhi The state of Jammu and Kashmir is located in the north-western region of India, in a complex of the Himalayan ranges with marked relief variation, snow- capped summits, antecedent drainage, complex geological structure and rich temperate flora and fauna. The vast mountain range of Himalayas from time immemorial stirred the imagination of the human mind and engaged the human psyche. The Hindu Rishis of India coined the word ―Himalaya‖—for Him, ―snow‖ and Alaya, ―the abode‖ for this mountain system and this name has rightly persisted in lexicon in human imagery. The Himalaya has exerted a personal and profound influence on generations of our people and continues to do so. It has given us mighty rivers, large wetlands, dense forests, etc. Himalaya has shaped our mythology, folklore, music, creativity and forms of worship. Its impact is both on social life and spiritual consciousness. India‘s most outstanding poet Kalidas has called Himalaya the ‗measuring rod of the earth‘, in one of his famous lyrical drama, Kumarasambhavam: In the north (of India), there is a mighty mountain by the name Himalaya—the abode of perpetual snow, fittingly called the Lord of mountains, animated by divinity and its soul and internal spirit. Spanning the wide land from the eastern to the western sea, he stands as it were like the measuring rod of the earth. Geomorphology The territories of Jammu, Kashmir, Ladakh and Gilgit form the State of Jammu and Kashmir. The entire State lies between 32.17" and 36.58" North altitude and East to West, the State lies between 73.26" and 80.30" longitude. -

Jr. Statistical Assistant

101 C QUESTION BOOKLET Q.B. Number: 101 Jr. Statistical Assistant INSTRUCTIONS Roll Number: Q.B. Series: C Please read the following instructions carefully. 9) For each answer as shown in the example below. The CORRECT and the WRONG method of darkening the 1) Mark carefully your Roll Number, Question Booklet CIRCLE on the OMR sheet are given below. Number and series of the paper on the OMR Answer Sheet and sign at the appropriate place. Write your Roll number Correct Method Wrong Method on the question booklet. 2) Strictly follow the instructions given by the Centre Supervisor / Room invigilator and those given on the Question Booklet. Please ensure you fill all the required details and shade the bubbles correctly on the OMR 10) In view of the tight time span, do not waste your time on Answer Sheet. a question which you find to be difficult. Go on solving questions one by one and come back to the difficult 3) Please mark the right responses ONLY with Blue/Black questions at the end. ball point pen. USE OF PENCIL AND GEL-PEN IS NOT ALLOWED. 11) DO NOT make any stray marks anywhere on the OMR Answer Sheet. DO NOT fold or wrinkle the OMR Answer 4) Candidates are not allowed to carry any papers, notes, Sheet. Rough work MUST NOT be done on the answer books, calculators, cellular phones, scanning devices, sheet. Use your question booklet for this purpose. pagers etc. to the Examination Hall. Any candidate found using, or in possession of such unauthorized material, indulging in copying or impersonation or adopting unfair means, is liable to be summarily disqualified and may be subjected to penal action. -

Indian River System

INDIAN RIVER SYSTEM Major River System – The Indus River System The Indus arises from the northern slopes of the Kailash range in Tibet near Lake Manasarovar. ❖ It has a large number of tributaries in both India and Pakistan and has a total length of about 2897 km from the source to the point near Karachi where it falls into the Arabian Sea out of which approx 700km lies in India. ❖ It enters the Indian Territory in Jammu and Kashmir by forming a picturesque gorge. ❖ In the Kashmir region, it joins with many tributaries – the Zaskar, the Shyok, the Nubra and the Hunza. ❖ It flows between the Ladakh Range and the Zaskar Range at Leh. ❖ It crosses the Himalayas through a 5181 m deep gorge near Attock, which is lying north of Nanga Parbat. The major tributaries of the Indus River in India are Jhelum, Ravi, Chenab, Beas, and Sutlej. Major River System – The Brahmaputra River System The Brahmaputra originates from Mansarovar Lake, which is also a source of the Indus and Sutlej. ❖ It is 3848kms long, a little longer than the Indus River. ❖ Most of its course lies outside India. ❖ It flows parallel to the Himalayas in the eastward direction. When it reaches Namcha Barwa, it takes a U-turn around it and enters India in the state of Arunachal Pradesh. ❖ Here it is known as the Dihang River. In India, it flows through the states of Arunachal Pradesh and Assam and is connected by several tributaries. ❖ The Brahmaputra has a braided channel throughout most of its length in Assam. -

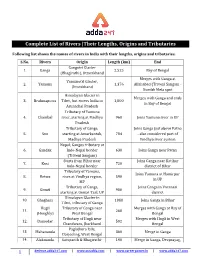

1 Complete List of Rivers |Their Lengths, Origins and Tributaries

Complete List of Rivers |Their Lengths, Origins and Tributaries Following list shows the names of rivers in India with their lengths, origins and tributaries. S.No. Rivers Origin Length (km) End Gangotri Glacier 1. Ganga 2,525 Bay of Bengal (Bhagirathi), Uttarakhand Merges with Ganga at Yamunotri Glacier, 2. Yamuna 1,376 Allahabad (Triveni Sangam - Uttarakhand Kumbh Mela spot Himalayan Glacier in Merges with Ganga and ends 3. Brahmaputra Tibet, but enters India in 1,800 in Bay of Bengal Arunachal Pradesh Tributary of Yamuna 4. Chambal river, starting at Madhya 960 Joins Yamuna river in UP Pradesh Tributary of Ganga, Joins Ganga just above Patna 5. Son starting at Amarkantak, 784 - also considered part of Madhya Pradesh Vindhya river system Nepal; Ganges tributary at 6. Gandak Indo-Nepal border 630 Joins Ganga near Patna (Triveni Sangam) Starts from Bihar near Joins Ganga near Katihar 7. Kosi 720 Indo-Nepal border district of Bihar Tributary of Yamuna, Joins Yamuna at Hamirpur 8. Betwa rises at Vindhya region, 590 in UP MP Tributary of Ganga, Joins Ganga in Varanasi 9. Gomti 900 starting at Gomat Taal, UP district Himalayan Glacier in 10. Ghaghara 1080 Joins Ganga in Bihar Tibet, tributary of Ganga Hugli Tributary of Ganga near Merges with Ganga at Bay of 11. 260 (Hooghly) West Bengal Bengal Tributary of Hugli near Merges with Hugli in West 12. Damodar 592 Chandwara, Jharkhand Bengal Paglajhora falls, 13. Mahananda 360 Merge in Ganga Darjeeling, West Bengal 14. Alaknanda Satopanth & Bhagirathi- 190 Merge in Ganga, Devprayag, 1 defence.adda247.com | www.sscadda.com | www.careerpower.in | www.adda247.com S.No. -

Zaskar Basin, Jammu Kashmir)

Current Trends in Technology and Science ISSN: 2279- 0535. Volume: 3, Issue: 3(Apr-May 2014) Geomorphological Mapping of Remote Area Using RS & GIS Technology of Doda Catchment (Zaskar Basin, Jammu Kashmir) Shashikant JRF, Haryana Space Applications Centre (HARSAC),[email protected] Pallavi Singh Student, University of Rajasthan R. D. Doi Professor, University of Rajasthan- Jaipur Abstract – Doda catchment area had remained activities. Geomorphological mapping allows an almost unknown for decades because of the improved understanding of Watershad management, inaccessibility and political restrictions. In the ground water exploration, and land use planning. present study, geomorphological mapping using Remote sensing technology has been found remote sensing techniques have been carried out in useful in generating geomorphological map, because of the Doda catchment of Zaskar Basin (Jammu & diverse and inaccessible terrain condition. [1] Kashmir). Uses of remote sensing and GIS Remotely sensed data has unique advantage over techniques have been proned indispensable in conventional data collection techniques in the study of geomorphological study. In the present investigation geomorphology, as physiographical and geo-structural an attempt is being made to use the NRIS (Natural parameters are mostly discernible on the imagery. [2] Resource Information System) standard for Geomorphology-Landform is a three-dimensional feature geomorphic mapping. Likewise, delineation of study on the earth surface formed by natural processes. Typically area is based on Watershad atlas of India (1990). landforms include volcanoes, plateaus, folded mountain Denudational hill is predominating in the study area ranges, streams etc. Geomorphology is the science that covering 41 percent of its geographical area. studies the nature and history of landforms and deposition Structural hills are second predominating features of that created them. -

Rangtik Tokpo: Chakdor Ri, Jamyang Ri, and Other Ascents India, Zanskar

AAC Publications Rangtik Tokpo: Chakdor Ri, Jamyang Ri, and Other Ascents India, Zanskar Anastasija Davidova and I visited the valley of Rangtik Tokpo in 2016 (AAJ 2017), and I decided to return in 2017 with Matjaz Dusic and Tomaz Zerovnik. This valley and surrounding areas to the south of the Doda River are infrequently visited by mountaineers. Summits rise to around 6,400m, but in terms of scale, the ridges and faces are more like those of the Alps, and there is great potential for first ascents at all grades. Approaches from villages along the Kargil-Padum road are not long; most mountains can be reached in one day. We established a base camp in the Rangtik valley at 4,926m (33°28'30"N, 76°45'13”E). From here we made three first ascents. In recent times mountaineers have made few known visits to this valley. In 2008 Spanish climbed Shawa Kangri (5,728m) via the route Rolling Stones (AAJ 2010). In 2012 the Japanese explorer Kimikazu Sakamoto, and friends, visited the neighboring Haptal Valley and produced a good sketch map of the area, including the Rangtik peaks, but they didn't visit the Rangtik Valley. In 2016 Anastasija and I made the first ascent of Remalaye West (6,266m), but it was obvious the east summit was higher. Matjaz, Tomaz, and I decided to make the east (main) top of Remalaye (H5 on the Sakamoto map) our acclimatization climb. We left base camp on July 21 and, following our 2016 route, climbed to 5,900m, where we bivouacked. -

Hidden Zanskar Exploration of the Korlomshe Tokpo1

DEREK BUCKLE Hidden Zanskar Exploration of the Korlomshe Tokpo1 Hidden Zanskar: the team named Peak 5916, left, ‘Kusyabla’, the Ladakhi word for monk. The peak on the right is Peak 5947, called ‘Temple’. (All images Derek Buckle) or our 2015 expedition to India, we were again attracted to the Zanskar Fregion of Ladakh, drawn by its relative remoteness, opportunities for exploration and the chance to attempt high, hitherto unclimbed mountains. A further potential advantage was that Zanskar, blocked as it is by the Himalaya to the south, is largely protected from the impact of the monsoon, with an arid terrain similar to that of Tibet. Having previously climbed in Knut Tønsberg on the first ascent of Temple (5947m). Zanskar’s Pensilungpa valley, the source of the Suru river2, we were keen to travel further south to investigate one or more of the valleys closer to This arduous journey involves some 236km of backbreaking unmade Padam, situated at the junction of the Doda and Zanskar rivers. Padam is track that is often washed out, although the need to maintain access to Padam currently accessed via a single road from Kargil, on the main road between ensures it is kept navigable. Everything is likely to change when the embry- Leh and Srinagar. The Padam road initially follows the Suru to the Pensi La onic direct road from Leh, following the Zanskar river itself, is completed. and then the Doda river from the pass. The likely impact of this new road is already evident in Padam, where hotels and other new buildings are under construction, although it may be several 1.