Winter Breeding As a Common Occurrence in the Ringed

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Abundance, Distribution, Population Structure, and Substrate Use of Ambystoma Altamirani Along the Arroyo Los Axolotes, State of Mexico, Mexico

Herpetological Conservation and Biology 15(1):188–197. Submitted: 16 August 2019; Accepted: 23 February 2020; Published: 30 April 2020. ABUNDANCE, DISTRIBUTION, POPULATION STRUCTURE, AND SUBSTRATE USE OF AMBYSTOMA ALTAMIRANI ALONG THE ARROYO LOS AXOLOTES, STATE OF MEXICO, MEXICO VIRIDIANA VILLARREAL HERNÁNDEZ1, GEOFFREY R. SMITH2, RAYMUNDO MONTOYA AYALA3, AND JULIO A. LEMOS-ESPINAL1,4 1Laboratorio de Ecología - Unidad de Biotecnología y Prototipos, Facultad de Estudios Superiores Iztacala, Avendina Los Barrios 1, Los Reyes Iztacala, Tlalnepantla, Estado de México, 54090, México 2Department of Biology, Denison University, Granville, Ohio 43023, USA 3Laboratorio de Cómputo - Unidad de Biotecnología y Prototipos, Facultad de Estudios Superiores Iztacala, Avenida Los Barrios 1, Los Reyes Iztacala, Tlalnepantla, Estado de México, 54090, México 4Corresponding author: e-mail: [email protected] Abstract.—Ambystomatid salamanders in central Mexico are confronted by anthropogenic threats that can limit their distribution and abundance. Ambystoma altamirani (Mountain Stream Siredon) is listed as Endangered by the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN) Red List and as Threatened by the Mexican government. We report on the distribution, abundance, occupancy, population structure, and substrate use of A. altamirani, a stream dwelling salamander, along the Arroyo los Axolotes, Sierra de las Cruces, Mexico. We observed A. altamirani at least once during repeated surveys between February 2018 to December 2018 in 24 of 25 permanent 5-m long reaches separated by 40 m. The best model for occupancy had constant occupancy, detection, extinction, and colonization probabilities. Sites that dried at some time during the study had fewer observed individuals than those that did not dry. Size structure was relatively constant throughout the year, except for the appearance of small larvae in May, June, and July. -

Ouachita Mountains Ecoregional Assessment December 2003

Ouachita Mountains Ecoregional Assessment December 2003 Ouachita Ecoregional Assessment Team Arkansas Field Office 601 North University Ave. Little Rock, AR 72205 Oklahoma Field Office 2727 East 21st Street Tulsa, OK 74114 Ouachita Mountains Ecoregional Assessment ii 12/2003 Table of Contents Ouachita Mountains Ecoregional Assessment............................................................................................................................i Table of Contents ........................................................................................................................................................................iii EXECUTIVE SUMMARY..............................................................................................................1 INTRODUCTION..........................................................................................................................3 BACKGROUND ...........................................................................................................................4 Ecoregional Boundary Delineation.............................................................................................................................................4 Geology..........................................................................................................................................................................................5 Soils................................................................................................................................................................................................6 -

Predation and Competition Among Larval Salamanders: The

PREDATION AND COMPETITION AMONG LARVAL SALAMANDERS: THE INFLUENCE OF DENSITY DEPENDENCE, PHENOLOGY, FOOD WEB STRUCTURE AND HABITAT COMPLEXITY A Dissertation Presented to the Faculty of the Graduate School at the University of Missouri-Columbia In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy by THOMAS LEE ANDERSON Dr. Raymond D. Semlitsch, Dissertation Advisor MAY 2016 Dedicated to Raymond D. Semlitsch and Rosemary S. Anderson ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS The number of people that contribute to someone completing a dissertation is innumerable. I owe a great of my development as a scientist to Ray Semlitsch, who pushed me to be better in every possible way. I would not be where I am today without your guidance, advice and support. I will miss the visits to your office to work out some complex problem and instead talking about hunting. Completing this work would not have been possible without the experiences I had prior to graduate school, made possible by Dr. Chris Floyd and the Rocky Mountain Biological Lab, Katie Derr, Dane Cramer and the E.B. Forsythe NWR, and Doug Tempel, Vince Berigan and Sheila Whitmore at Blodgett Forest Station. At Mizzou, this work would not have been possible or nearly as enjoyable without the help of an amazing lab group: Bill Peterman, Grant Connette, Mark Mackey, Britt Ousterhout, Dana Drake, Katie O’Donnell, Jake Burkhart, Freya Rowland, Arianne Messerman, Julia Earl, Rachelle Riegerix, Shannon Pittman, Tom Luhring, Mike Osbourn, and Holly Puglis. All of you made an office space that will be unmatched. I would like thank Ricardo Holdo, Matt Gompper, Debbie Finke and Rex Cocroft for always supporting projects that I was working on, and providing feedback on ideas and manuscripts. -

Standard Common and Current Scientific Names for North American Amphibians, Turtles, Reptiles & Crocodilians

STANDARD COMMON AND CURRENT SCIENTIFIC NAMES FOR NORTH AMERICAN AMPHIBIANS, TURTLES, REPTILES & CROCODILIANS Sixth Edition Joseph T. Collins TraVis W. TAGGart The Center for North American Herpetology THE CEN T ER FOR NOR T H AMERI ca N HERPE T OLOGY www.cnah.org Joseph T. Collins, Director The Center for North American Herpetology 1502 Medinah Circle Lawrence, Kansas 66047 (785) 393-4757 Single copies of this publication are available gratis from The Center for North American Herpetology, 1502 Medinah Circle, Lawrence, Kansas 66047 USA; within the United States and Canada, please send a self-addressed 7x10-inch manila envelope with sufficient U.S. first class postage affixed for four ounces. Individuals outside the United States and Canada should contact CNAH via email before requesting a copy. A list of previous editions of this title is printed on the inside back cover. THE CEN T ER FOR NOR T H AMERI ca N HERPE T OLOGY BO A RD OF DIRE ct ORS Joseph T. Collins Suzanne L. Collins Kansas Biological Survey The Center for The University of Kansas North American Herpetology 2021 Constant Avenue 1502 Medinah Circle Lawrence, Kansas 66047 Lawrence, Kansas 66047 Kelly J. Irwin James L. Knight Arkansas Game & Fish South Carolina Commission State Museum 915 East Sevier Street P. O. Box 100107 Benton, Arkansas 72015 Columbia, South Carolina 29202 Walter E. Meshaka, Jr. Robert Powell Section of Zoology Department of Biology State Museum of Pennsylvania Avila University 300 North Street 11901 Wornall Road Harrisburg, Pennsylvania 17120 Kansas City, Missouri 64145 Travis W. Taggart Sternberg Museum of Natural History Fort Hays State University 3000 Sternberg Drive Hays, Kansas 67601 Front cover images of an Eastern Collared Lizard (Crotaphytus collaris) and Cajun Chorus Frog (Pseudacris fouquettei) by Suzanne L. -

Observation of Predation by a Lycosid Spider on a Captive-Reared Salamander Larva (Ambystoma Annulatum)

Herpetology Notes, volume 8: 455-457 (published online on 12 August 2015) Observation of predation by a lycosid spider on a captive-reared salamander larva (Ambystoma annulatum) Adam Crane1,* and Alicia Mathis2 Salamanders in the family Ambystomatidae oviposit development in some amphibian species (Warkentin, in ponds where their offspring hatch and develop as 2011; Boone et al., 2002). The egg mass was placed in aquatic larvae for a period of weeks to years before a 19 L bucket containing 6 L of pond water. An airstone metamorphosizing and moving onto land (Wells, 2010). provided aeration at the surface of the water from a During their larval stage, individuals face a variety of battery powered pump. The eggs were transported by predators such as diving beetle larvae, wading birds, vehicle to our laboratory (Fig. 1A) where they were and other salamanders (Duellman and Trueb, 1986). held in an aerated plastic container (31×17.5×10.5 cm). Wolf spiders (Lycosidae) are known predators of some Upon hatching, larvae were fed by adding pond water frogs (Formanowicz et al., 1981) and terrestrial eggs of containing daphnia. As larvae grew over the winter, some salamanders (Villa et al., 1982). In experimental we switched their diet to live bloodworms (3 feedings trials, Rubbo et al. (2003) found that wolf spiders would of 5-10 worms per week) and moved larvae into feed on terrestrial spotted salamanders (Ambystoma individual plastic containers (10×10×9 cm; Fig. 1B) to maculatum) by envenomation with their chelicerae. prevent cannibalism. Water changes with dechlorinated However, we are not aware of any literature reporting tap water were also conducted three times per week. -

Newsletter #30 (2017)

Number 30 2017 Copyright 2017 Missouri Herpetological Association MISSOURI HERPETOLOGICAL ASSOCIATION NEWSLETTER NO. 30 Contents INTRODUCTION ............................................................................................................................................... 2 ANNOUNCEMENTS ........................................................................................................................................... 2 ABSTRACTS OF PAPERS PRESENTED AT THE THIRTIETH ANNUAL MEETING OF THE MHA ...................... 3 MYSTERY SALAMANDER FROM MISSOURI. T. Anderson TRANSCRIPTOMIC SIGNATURES REVEAL BIOMARKERS FOR UNDERSTANDING AMPHIBIAN STRESS. T.A. Clay, M.L. Tregulia, M.A. Steffen, A.L. Trujano-Alvarez and R.M. Bonett INFLUENCE OF SEX, TERRITORIAL OWNERSHIP, AND SPECIES ON AGGRESSION IN TWO SPECIES OF SALAMANDER. C. Lynn and A. Mathis BEHAVIORAL FLEXIBILITY IN THE PRAIRIE LIZARD, Sceloporus consobrinus. H. Hoekzema, S. Ruck and M. Leal DOES “BODY CONDITION” ACCURATELY PREDICT ENERGY RESERVES IN LIZARDS? M. Gifford and C. Robinson DO OKLAHOMA SALAMANDERS RESPOND TO THE SCENT OF AQUATIC PREDATORS AND ALARM CUES AFTER METAMORPHOSIS? S. Johnson and A. Mathis BIOCHEMICAL MECHANISMS INFLUENCING COUNTER-GRADIENT VARIATION IN LIZARD DEVELOPMENT. A.N. Lenard and M.E. Gifford FIRST SEASON RESULTS ON THE SPATIAL ECOLOGY AND HABITAT SELECTION OF PYGMY RATTLESNAKES (Sistrurus miliarius) IN SOUTHWESTERN MISSOURI. D. Maag and B. Greene BEHAVIORAL RESPONSES OF COTTONMOUTHS TO CONSPECIFIC CLOACAL SECRETIONS DURING FEEDING EVENTS. A. Meinders -

Salamander News

Salamander News No. 12 December 2014 www.yearofthesalamander.org A Focus on Salamanders at the Toledo Zoo Article and photos by Timothy A. Herman, Toledo Zoo In the year 2000, the Toledo Zoo opened the award-winning “Frogtown, USA” exhibit, showcasing amphibians native to Ohio, including one display housing a variety of plethodontid salamanders. Captive husbandry of lungless salamanders of the family Plethodontidae had previously been extremely rudimentary, and few people had maintained these amphibians in zoos. In this exhibit in 2007, the first captive reproduction of the Northern Slimy Salamander (Plethodon glutinosus) was achieved in a zoo setting, followed shortly thereafter by the Four-toed Salamander (Hemidactylium scutatum) A sample of the photogenic salamander diversity encountered during MUSHNAT/Toledo Zoo in an off-display holding fieldwork in Guatemala, clockwise from top left:Oedipina elongata, Bolitoglossa eremia, Bolitoglossa salvinii, Nyctanolis pernix. area. Inside: This exhibit was taken down and overhauled for Year of the Frog in page 2008, giving us the opportunity to design, from the ground up, a facility Year of the Salamander Partners 3 incorporating the lessons learned from the first iteration. Major components Ambystoma bishopi Husbandry 5 of this new Amazing Amphibians exhibit included a renovated plethodontid Western Clade Striped Newts 7 salamander display, holding space to develop techniques for the captive Giant Salamander Mesocosms 8 reproduction of plethodontid salamanders, and four biosecure rooms to 10 work with imperiled amphibians with the potential for release back into the Georgia Blind Salamanders wild. One of these rooms was constructed with the capacity to maintain Chopsticks for Salamanders 12 environmental conditions for high-elevation tropical salamanders. -

ABSTRACTS 29 Reptile Ecology I, Highland A, Sunday 15 July 2018

THE JOINT MEETING OF ASIH SSAR HL lcHTHYOLOGISTS & HERPETOLOGISTS ROCHESTER, NEW YORK 2018 ABSTRACTS 29 Reptile Ecology I, Highland A, Sunday 15 July 2018 Curtis Abney, Glenn Tattersall and Anne Yagi Brock University, St. Catharines, Ontario, Canada Thermal Preference and Habitat Selection of Thamnophis sirtalis sirtalis in a Southern Ontario Peatland Gartersnakes represent the most widespread reptile in North America. Despite occupying vastly different biogeoclimatic zones across their range, evidence suggests that the thermal preferenda (Tset) of gartersnakes has not diverged significantly between populations or different Thamnophis species. The reason behind gartersnake success could lie in their flexible thermoregulatory behaviours and habitat selection. We aimed to investigate this relationship by first identifying the Tset of a common gartersnake species (Thamnophis sirtalis sirtalis) via a thermal gradient. We then used this Tset parameter as a baseline for calculating the thermal quality of an open, mixed, and forested habitat all used by the species. We measured the thermal profiles of these habitats by installing a series of temperature-recording analogues that mimicked the reflectance and morphology of living gartersnakes and recorded environmental temperatures as living snakes experience them. Lastly, we used coverboards to survey the current habitat usage of T. s. sirtalis. Of the three habitats, we found that the open habitat offered the highest thermal quality throughout the snake’s active season. In contrast, we recorded the greatest number of snakes using the mixed habitat which had considerably lower thermal quality. Although the open habitat offered the greatest thermal quality, we regularly recorded temperatures exceeding the upper range of the animals’ thermal preference. -

SICB 2020 Annual Meeting Abstracts

The Society for Integrative and Comparative Biology with the American Microscopical Society The Crustacean Society SICB 2020 ABSTRACT BOOK January 3-7, 2020 JW Marriott Austin • Austin, TX Abstract Book SICB does not assume responsibility for any inconsistencies or errors in the abstracts for contributed paper and poster presentations. We regret any possible omissions, changes and/ or additions not reflected in this abstract book. SICB 2020 Annual Meeting Abstracts 127-1 AARON GOODMAN, AMG*; LAUREN ESPOSITO, LAE; 56-5 ABBOTT, EA*; DIXON, GB; MATZ, MV; University of California Academy of Sciences, California Academy of Sciences ; Texas; [email protected] [email protected] Disentangling coral stress and bleaching responses by comparing Spatial and Ecological Niche Partitioning in Congeneric Scorpions gene expression in symbiotic partners Species in the scorpion genus Centruroides Marx, 1890 (Scorpiones: Coral bleaching—the disruption of the symbiosis between a coral Buthidae) are good candidates to study ecological niche partitioning host and its endosymbiotic algae—is associated with environmental due to their habitat plasticity, widespread geographic distribution, stressors. However, the molecular processes are not well understood, and presence of cryptic species. Currently, three species belonging to and no studies have disentangled the transcriptional bleaching three subgroups of Centruroides are distributed along the Isthmus of response from the stress response. In order to characterize general Tehuantepec in southern Mexico, presenting a rare opportunity to stress response, specific stress responses, and the bleaching response, study niche partitioning within a single genus. We examined the we isolated host and symbiont RNA from fragments of Acropora environmental, substrate, and habitat preferences of Centruroides millepora which were exposed to 5 different stress treatments. -

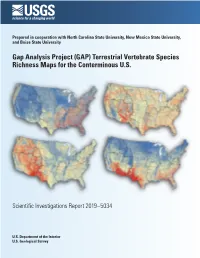

Gap Analysis Project (GAP) Terrestrial Vertebrate Species Richness Maps for the Conterminous U.S

Prepared in cooperation with North Carolina State University, New Mexico State University, and Boise State University Gap Analysis Project (GAP) Terrestrial Vertebrate Species Richness Maps for the Conterminous U.S. Scientific Investigations Report 2019–5034 U.S. Department of the Interior U.S. Geological Survey Cover. Mosaic of amphibian, bird, mammal, and reptile species richness maps derived from species’ habitat distribution models of the conterminous United States. Gap Analysis Project (GAP) Terrestrial Vertebrate Species Richness Maps for the Conterminous U.S. By Kevin J. Gergely, Kenneth G. Boykin, Alexa J. McKerrow, Matthew J. Rubino, Nathan M. Tarr, and Steven G. Williams Prepared in cooperation with North Carolina State University, New Mexico State University, and Boise State University Scientific Investigations Report 2019–5034 U.S. Department of the Interior U.S. Geological Survey U.S. Department of the Interior DAVID BERNHARDT, Secretary U.S. Geological Survey James F. Reilly II, Director U.S. Geological Survey, Reston, Virginia: 2019 For more information on the USGS—the Federal source for science about the Earth, its natural and living resources, natural hazards, and the environment—visit https://www.usgs.gov or call 1–888–ASK–USGS (1–888–275–8747). For an overview of USGS information products, including maps, imagery, and publications, visit https://store.usgs.gov. Any use of trade, firm, or product names is for descriptive purposes only and does not imply endorsement by the U.S. Government. Although this information product, for the most part, is in the public domain, it also may contain copyrighted materials as noted in the text. -

Species Status Assessment for the Reticulated Flatwoods Salamander (Ambystoma Bishopi) Version 1.0

SSA for Reticulated Flatwoods Salamander Version 1.0, March 2020 Species Status Assessment for the Reticulated Flatwoods Salamander (Ambystoma bishopi) Version 1.0 (Credit: Kelly Jones, Virginia Tech) March 2020 Panama City Field Office Panama City, Florida For the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service South Atlantic - Gulf Region SSA for Reticulated Flatwoods Salamander Version 1.0, March 2020 Acknowledgments Prepared by Dr. Susan Walls (U.S. Geological Survey) and Anna Farmer (Florida Fish and Wildlife Conservation Commission) with support from Dr. Sean Blomquist (USFWS), Arianne Messerman (University of Missouri), John Palis, Kelly Jones (Virginia Tech University), Dr. Carola Haas (Virginia Tech University), the staff and support of the San Antonio Zoo, Bekky Muscher-Hodges, Dr. Dante Fenolio, Charlie Abeles (Longleaf Alliance), George Brooks (PhD Candidate, Virginia Tech University), Thomas Floyd (Georgia Dept of Natural Resources), Rodney Felix (Eglin Air Force Base Office of Resource Management), Jamie Barichivich (U.S. Geological Survey), Dr. Katie O’Donnell (U.S. Geological Survey), Dr. Brooke Talley (Florida Fish and Wildlife Conservation Commission), Lorraine Ketzler (USFWS). Valuable peer review of the document was provided by Dr. Kurt Buhlmann University of Georgia, Savannah River Ecology Laboratory and Dr. David Bishop, The Nature Conservancy. EXECUTIVE SUMMARY This species status assessment (SSA) reports the results of a comprehensive status review for the reticulated flatwoods salamander (Ambystoma bishopi), documents the species’ historical conditions, and provides estimates of current and future conditions under a range of different scenarios. This species was federally listed in 1999 (64 FR 15691) as a threatened species under the Endangered Species Act of 1973 as amended (Act). -

The Confluence

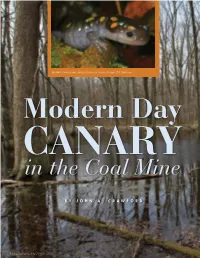

Spotted salamander, Ambystoma maculatum (Image: Bill Peterman) Modern Day CANARY in the Coal Mine BY JOHN A. CRAWFORD 4 | The Confluence | Fall/Winter 2012 Throughout the course of early American more pressing issues in American society, such history, the natural environment was viewed as the two world wars and the Korean conflict. as a wilderness to be conquered and used for In 1962, Rachel Carson published Silent man’s benefit. During the latter portion of Spring, which is largely recognized as the the nineteenth century, this attitude began to book that jumpstarted a period in American change as American writers such as Henry environmental history known as the David Thoreau and Ralph Waldo Emerson Reawakening. In her book, Carson documented began to draw the public’s attention to the detrimental effects of pesticides on the natural areas and environmental problems environment (focusing specifically on birds). arising due to human influences. Further, Her book ultimately led to the ban on the use George Perkins Marsh published Man and of the pesticide DDT in 1972. On April 22, Nature (1864), in which he documented the 1970, the U.S. observed the first Earth Day, effects of humans on the environment. In this and memberships soared in organizations landmark book, Marsh concluded that ancient such as the Sierra Club, the National Audubon Mediterranean civilizations ultimately failed Society, and the National Wildlife Federation.2 due to environmental degradation (primarily, As seen previously, American interest in deforestation and pollution). He then noted that environmental issues eroded when faced with the same patterns were beginning to develop in the economic crises of the late 1970s and early the United States.