1:1 Aims Chapter One Introduction

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Report to Office of Water Science, Department of Science, Information Technology and Innovation, Brisbane

Lake Eyre Basin Springs Assessment Project Hydrogeology, cultural history and biological values of springs in the Barcaldine, Springvale and Flinders River supergroups, Galilee Basin and Tertiary springs of western Queensland 2016 Department of Science, Information Technology and Innovation Prepared by R.J. Fensham, J.L. Silcock, B. Laffineur, H.J. MacDermott Queensland Herbarium Science Delivery Division Department of Science, Information Technology and Innovation PO Box 5078 Brisbane QLD 4001 © The Commonwealth of Australia 2016 The Queensland Government supports and encourages the dissemination and exchange of its information. The copyright in this publication is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 3.0 Australia (CC BY) licence Under this licence you are free, without having to seek permission from DSITI or the Commonwealth, to use this publication in accordance with the licence terms. You must keep intact the copyright notice and attribute the source of the publication. For more information on this licence visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/3.0/au/deed.en Disclaimer This document has been prepared with all due diligence and care, based on the best available information at the time of publication. The department holds no responsibility for any errors or omissions within this document. Any decisions made by other parties based on this document are solely the responsibility of those parties. Information contained in this document is from a number of sources and, as such, does not necessarily represent government or departmental policy. If you need to access this document in a language other than English, please call the Translating and Interpreting Service (TIS National) on 131 450 and ask them to telephone Library Services on +61 7 3170 5725 Citation Fensham, R.J., Silcock, J.L., Laffineur, B., MacDermott, H.J. -

Annual Report 2013 - 2014

Lockhart River Aboriginal Shire Council Annual Report 2013 - 2014 Page 0 Lockhart River Aboriginal Shire Council TABLE OF CONTENTS INTRODUCTION ............................................................................................................................ 2 MAP OF LOCKHART RIVER ....................................................................................................... 3 MAP OF LOCKHART RIVER TOWNSHIP .................................................................................. 4 COUNCIL VISION, MISSION STATEMENT AND GUIDING VALUES .................................... 5 MAYOR’S REPORT ...................................................................................................................... 6 CHIEF EXECUTIVE OFFICER’S REPORT ................................................................................. 7 LOCKHART RIVER HISTORY ..................................................................................................... 8 FACILITIES AND SERVICES ..................................................................................................... 12 PRIVATE ENTERPRISES ........................................................................................................... 15 OUR COUNCIL ............................................................................................................................ 17 ELECTED MEMBERS ................................................................................................................................................. 18 COUNCILLORS -

Guided by Her: Aboriginal Women's Participation in Australian Expeditions

5 Guided by her: Aboriginal women’s participation in Australian expeditions Allison Cadzow I was compelled in a great measure to be guided by her. She was acquainted with all their haunts and was a native of Port Davey, belonging to this tribe and having a brother and other relatives living among them, [Low. Ger Nown] was her native place. Though I knew she intended sojourning with them, yet there was no alternative but to follow her suggestions … George Augustus Robinson discussing Dray’s guiding in Tasmania (6 April 1830) Our female guide, who had scarcely before ventured to look up, stood now boldly forward, and addressed the strange tribe in a very animated and apparently eloquent manner; and when her countenance was thus lighted up, displaying fine teeth, and great earnestness of manner, I was delighted to perceive what soul the woman possessed, and could not but consider our party fortunate in having met with such an interpreter. Thomas Mitchell discussing Turandurey’s guiding in New South Wales (12 May 1836) The Aboriginal women mentioned above are clearly represented as guides and appear in plain view; they are not in hiding. While women did hide from white expedition members – for good reason considering 85 BRoKERS AND BouNDARIES the frequent violence of white people towards them – this was not the only reaction they had. Historians have largely ignored Aboriginal women’s involvement in exploration expeditions, though there are some notable exceptions in the work of Henry Reynolds, Lyndall Ryan and Donald Baker. Some other authors who have attended to them, such as Philip Clarke, imply that women were invariably hidden away during encounters, suggesting they were not actively involved in expeditions.1 Even when women did hide, this was not necessarily the end of the story, as they sometimes re-emerged after assessing the situation. -

Lands of the Isaac-Comet Area, Queensland

IMPORTANT NOTICE © Copyright Commonwealth Scientific and Industrial Research Organisation (‘CSIRO’) Australia. All rights are reserved and no part of this publication covered by copyright may be reproduced or copied in any form or by any means except with the written permission of CSIRO Division of Land and Water. The data, results and analyses contained in this publication are based on a number of technical, circumstantial or otherwise specified assumptions and parameters. The user must make its own assessment of the suitability for its use of the information or material contained in or generated from the publication. To the extend permitted by law, CSIRO excludes all liability to any person or organisation for expenses, losses, liability and costs arising directly or indirectly from using this publication (in whole or in part) and any information or material contained in it. The publication must not be used as a means of endorsement without the prior written consent of CSIRO. NOTE This report and accompanying maps are scanned and some detail may be illegible or lost. Before acting on this information, readers are strongly advised to ensure that numerals, percentages and details are correct. This digital document is provided as information by the Department of Natural Resources and Water under agreement with CSIRO Division of Land and Water and remains their property. All enquiries regarding the content of this document should be referred to CSIRO Division of Land and Water. The Department of Natural Resources and Water nor its officers or staff accepts any responsibility for any loss or damage that may result in any inaccuracy or omission in the information contained herein. -

Mount Ommaney

Street Name Register Mount Ommaney Last updated : August 2020 MOUNT OMMANEY (established January 1970 – 3rd Centenary suburb) Originally named by Queensland Place Names Board on 1 July 1969. Name and boundaries confirmed by Minister for Survey and Valuation, Urban and Regional Affairs on 11 August 1975. Suburb The name is derived from hill feature, possibly named after John OMMANNEY, (1837-1856), nephew of Dr Stephen Simpson of Wolston House, OMMANNEY having been killed nearby in a fall from a horse. History Mount Ommaney was designed as a series of exclusive courts, many named after prominent Australian politicians and explorers, as well as artists from all genre of classical music. MOUNT OMMANEY A Abel Smith Crescent Sir Henry ABEL SMITH was Governor of Queensland 1958-1966 Archer Court ?? David ARCHER (1860-1900) was an explorer and botanist. In 1841 he took up Durandur Station in the Moreton district Arrabri Avenue Aboriginal word meaning “big mountain” (S.E. Endacott) renamed from Doonkuna (meaning ‘rising’) St., Jindalee in 1969 Augusta Circuit B Bartok Place Bela BARTOK (1881-1945) – Hungarian composer Beagle Place Name of an English ship used to survey the Australian coastline Becker Place Ludwig BECKER (?1808-1861) was an artist, explorer and naturalist Bedwell Place A surveyor on the survey ship ‘Pearl’ in the 1870s (BCC Archives) Bizet Close Georges BIZET (1838-1875) – French composer Blaxland Court Gregory BLAXLAND (1778-1853) was an explorer and pioneer farmer of Australia who in 1813 was in the first party to cross the Blue Mountains (NSW) in the Great Dividing Range Bondel Place Bounty Street Captain William Bligh’s ship ‘The Bounty’ Bowles Street After W L Bowles, a modern Australian sculptor Bowman Place Burke Court Robert O’Hara BURKE (1820-1861) and William WILLS in 1860 were the first explorers to cross Australia from south to north. -

Patterns of Persistence of the Northern Quoll Dasyurus Hallucatus in Queensland

Surviving the toads: patterns of persistence of the northern quoll Dasyurus hallucatus in Queensland. Report to The Australian Government’s Natural Heritage Trust March 2008 Surviving the toads: patterns of persistence of the northern quoll Dasyurus hallucatus in Queensland. Report submitted to the Natural Heritage Trust Strategic Reserve Program, as a component of project 2005/162: Monitoring & Management of Cane Toad Impact in the Northern Territory. J.C.Z. Woinarski1, M. Oakwood2, J. Winter3, S. Burnett4, D. Milne1, P. Foster5, H. Myles3, and B. Holmes6. 1. Department of Natural Resources Environment and The Arts, PO Box 496, Palmerston, NT, 0831. 2. Envirotek, PO Box 180, Coramba NSW 2450 3. PO Box 151, Ravenshoe Qld 4888; and School of Marine and Tropical Biology, James Cook University, Townsville. 4. PO Box 1219, Maleny 4552; [email protected] Box 1219, Maleny, 4552 5. “Bliss" Environment Centre, 1023D Coramba Rd, Karangi NSW 2450 6. 74 Scott Rd, Herston 4006; [email protected] Photos: front cover – Northern quoll at Cape Upstart. Photo: M. Oakwood & P. Foster CONTENTS Summary 2 Introduction 4 relevant ecology 7 Methods 8 northern quoll Queensland distributional database 8 field survey 8 Analysis 10 change in historical distribution 10 field survey 11 Results 12 change in historical distribution 12 field survey 14 Discussion 15 Acknowledgements 19 References 20 List of Tables 1. Locations of study sites sampled in 2006-07. 25 2. Environmental and other attributes recorded at field survey transects. 27 3. Frequency distribution of quoll records across different time periods. 30 4. Comparison of quoll and non-quoll records for environmental variables. -

2011-12-Annual-Report-Inc-Financial-Report.Pdf

2011 - 2012 Contents About Central Highlands Regional Council ................................................................ 2 Our Vision ................................................................................................................. 3 Our Mission ............................................................................................................... 3 Our Values and Commitment .................................................................................... 3 A Message from Our Mayor and CEO ....................................................................... 4 Our Mayor and Councillors April 28 2012 – June 30 2012 ......................................... 5 Our Mayor and Councillors 2011 – April 28 2012 ...................................................... 7 Our Senior Executive Team ...................................................................................... 9 Our Employees ....................................................................................................... 11 Community Financial Report ................................................................................... 13 Assessment of Council Performance in Implementing its Long Term Community Plan ................................................................................................................................ 19 Meeting Our Corporate Plan Objectives .................................................................. 19 Achievements by Department ................................................................................ -

Father Hayes and the Carnarvons

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by University of Queensland eSpace Father Hayes and the Carnarvons FATHER HAYES WAS A MEMBER OF THREE EXPEDITIONS ORGANISED BY THE QUEENSLAND BRANCH OF THE ROYAL GEOGRAPHICAL SOCIETY OF AUSTRALASIA TO THE CARNARVON RANGE IN 1937, 1938 AND 1940. ROSLYN FOLLETT RECOUNTS FATHER HAYES’ CONTRIBUTION TO THESE TRIPS. Following his ordination in 1918, Father British Museum scientific excursion Hayes’ first appointment was as Assistant- to the area, was appointed botanist. Priest at Ipswich. His interest in geology Theodore Culman and Al Burne were the originated there. photographers. “I was always going home with stones “When the party was chosen they were in my pocket. I told the priest in charge short of an ethnologist. Mr Culman that I was going to become a geologist asked Archbishop Duhig, whom he knew and he asked what the deuce that would through their association on various be”, Father Hayes recalled.1 charitable organisations, if he knew of anyone willing to join the expedition and Father Hayes’ chance to work as a Above: share the hardships of an arduous journey. Main: The Royal geologist began when he was invited to Archbishop Duhig at once suggested and Geographical Society of participate in a number of scientific trips released Father Leo Hayes”2 Australasia Expedition to the to the Carnarvons. In 1932, a section of Carnarvon Ranges in 1937. the Carnarvon Gorge had been declared a Father Hayes joined the party as geologist Father Hayes is fourth from national park, following lobbying from the and ethnologist. -

Plate 7. Vine Thicket (Type 3),Goodedulla National Park, West of Rockhampton (Site 73)

Plate 7. Vine thicket (type 3),Goodedulla National Park, west of Rockhampton (site 73). Note browning and loss of foliage due to extreme drought conditions (August 1994). Species include Backhousia kingii, Crown insularis, Owenia venosa, Geijera paniculata and Acalypha eretnorum (foreground). - - Plate 8. Interior of (type 3) vine thicket, "Cerberus", west of Marlborough (site 67). Species include Backhousia kingii, E.vcoecaria dallackyana, Guettardella putaininosa and Planclunzella cotinifolia var. pubescens. 142 CHAPTER FOUR A REGIONAL CONTEXT FOR VINE THICKET COMMUNITIES - FLORISTIC PATTERNS IN THE BRIGALOW BELT BIOGEOGRAPHIC REGION AND RELATIONSHIPS WITH ENVIRONMENTAL ATTRIBUTES, PARTICULARLY CLIMATE. Although the core area of distribution and major remnants of semi-evergreen vine thicket are located in central and southern Queensland, outliers of these communities occur extensively in the northern and southern Brigalow Belt Biogeographic Region. Time and other constraints resulted in the southern (i.e. north-western New South Wales) vine thickets being excluded from the detailed field survey (Chapter 3) and in the northern vine thickets being relatively under-sampled. The latter areas have since been included in a comprehensive floristic survey of northern inland vine thickets by Fensham (1995). Floristic data are available for several southern vine thicket locations (Floyd 1991, J.B.Williams, unpubl. lists), three of which were included in Webb, Tracey and Williams (1984) floristic analysis of Australian rainforests. It was considered desirable to test the robustness of the vine thicket classification/typology derived above (Chapter 3) using an enlarged floristic data set compiled across the entire Brigalow Belt Biogeographic Region. Inclusion of site data from Fenshams (1995) survey has two purposes; (i) to improve the intensity of sampling from the northern Brigalow Belt Biogeographic Region (see above) and (ii) to provide an opportunity to compare the vine thicket classifications from this study and that of Fensham, using a common data set. -

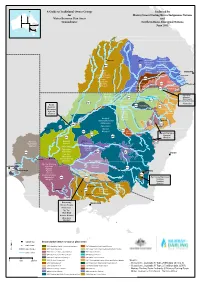

Guide to Traditional Owner Groups for WRP Areas Combined Maps

A Guide to Traditional Owner Groups Endorsed by for Murray Lower Darling Rivers Indigenous Nations Water Resource Plan Areas and Groundwater Northern Basin Aboriginal Nations June 2015 Nivelle River r e v i R e l a v i Nive River r e M M a Beechal Creek Langlo River r a n o a R i !( v Gunggari e Ward River Charleville r Roma Bigambul !( Guwamu/Kooma Barunggam Jarowair k e Bidjara GW22 e Kambuwal r GW21 «¬ C Euahlayi Mandandanji a «¬ Moola Creek l Gomeroi/Kamilaroi a l l Murrawarri Oa a k Bidjara Giabel ey Cre g ek n Wakka Wakka BRISBANE Budjiti u Githabul )" M !( Guwamu/Kooma Toowoomba k iver e nie R e oo Kings Creek Gunggari/Kungarri r M GW20 Hodgson Creek C Dalrymple Creek Kunja e !( ¬ n « i St George Mandandanji b e Bigambul Emu Creek N er Bigambul ir River GW19 Mardigan iv We Githabul R «¬ a e Goondiwindi Murr warri n Gomeroi/Kamilaroi !( Gomeroi/Kamilaroi n W lo a GW18 Kambuwal a B Mandandanji r r ¬ e « r g Rive o oa r R lg ive r i Barkindji u R e v C ie iv Bigambul e irr R r r n Bigambul B ive a Kamilleroi R rr GW13 Mehi River Githabul a a !( G Budjiti r N a ¬ w Kambuwal h « k GW15 y Euahlayi o Guwamu/Kooma d Gomeroi/Kamilaroi Paroo River B Barwon River «¬ ir GW13 Gomeroi/Kamilaroi Ri Bigambul Kambuwal ver Kwiambul Budjiti «¬ Kunja Githabul !( GW14 Kamilleroi Euahlayi Bourke Kwiambul «¬ GW17 Kambuwal Namo iver Narrabri ¬ i R « Murrawarri Maljangapa !( Gomeroi/Kamilaroi Ngemba Murrawarri Kwiambul Wailwan Ngarabal Ngarabal B Ngemba o g C a Wailwan Talyawalka Creek a n s Barkindji R !( t l Peel River M e i Wiradjuri v r Tamworth Gomeroi/Kamilaro -

Expeditions of the Phylogeny of World Tachinidae Project, Part II Eastern Australia

Wright State University CORE Scholar Biological Sciences Faculty Publications Biological Sciences 2014 Chasing tachinids ‘Down Under’: Expeditions of the phylogeny of World Tachinidae project, Part II Eastern Australia James E. O'Hara Pierfilippo Cerretti John O. Stireman III Wright State University - Main Campus, [email protected] Isaac S. Winkler Wright State University - Main Campus Follow this and additional works at: https://corescholar.libraries.wright.edu/biology Part of the Biology Commons, Ecology and Evolutionary Biology Commons, Entomology Commons, and the Systems Biology Commons Repository Citation O'Hara, J. E., Cerretti, P., Stireman, J. O., & Winkler, I. S. (2014). Chasing tachinids ‘Down Under’: Expeditions of the phylogeny of World Tachinidae project, Part II Eastern Australia. The Tachinid Times (27), 20-31. https://corescholar.libraries.wright.edu/biology/408 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Biological Sciences at CORE Scholar. It has been accepted for inclusion in Biological Sciences Faculty Publications by an authorized administrator of CORE Scholar. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Chasing tachinids ‘Down Under’ Expeditions of the Phylogeny of World Tachinidae Project Part II Eastern Australia Figure 2. Rutilia regalis Guérin- Méneville, one of the first tachinids described from Australia (from Guérin-Méneville 1831: pl. 21). Figure 1. Epiphyte-laden tree in the lush rainforest of Lamington National Park, Queensland. (Photo: P. Cerretti) Preamble Last year we documented in the pages of this newsletter an expedition to the Western Cape of South Africa in search of tachinids for the “Phylogeny of World Tachinidae” project (Cerretti et al. -

Carnarvon Station Reserve, Qld Camping Information

Carnarvon Station Reserve. Photo: Katrina Blake Carnarvon Station Reserve, Qld Camping Information Quick facts Acquired: 2001 Area: 59,000 ha Traditional owners: Bidjara Location: Central Highlands region, Qld, 212km north east of Augathella. Temperature (average min/max): Winter 1° to 26 °C. Summer 15° to 37°C. Annual rainfall: 700mm Camp site: Open 1June to 30 September. Minimum two night stay - Bookings are essential as sites are limited and need to fit around other activities and management requirements. Please do not plan to arrive on a Sunday. Complete the on-line registration form or for questions email [email protected] or call Katrina Blake 03 8610 9124 Essential: Vehicle 4WD with high clearance (no SUV/AWD vehicles). Emergency communication equipment: Satellite phone or EPIRB or SPOT or HF radio. Camping fees While there’s no camping fee, we ask instead people make a tax-deductible donation to help us undertake our work and maintain the visitor opportunities on this reserve. Donations can be made anytime online or forms are available at the reserve. Location Carnarvon Station Reserve is in south east central Queensland, to the South and west of Carnarvon National Park. It’s about 870km south west of Rockhampton and about 940km north west of Brisbane. Visitors can only access the reserve via Mt Tabor Rd from Augathella (203km) or Morven (230km). On leaving either of these towns allow 4 hours to reach the reserve. More detailed travel instructions will be provided on booking confirmation. Carnarvon Station homestead co-ordinates • Lat long decimal degrees -24.85196, 147.63398 • Lat long degrees minutes seconds -24°51'07.0560", 147°38'02.3280" • UTM E 564,052 N 7,251,295 Zone 55 Updated 11/3/2020 Enjoying the reserve You need a minimum stay of 2 nights, but we highly recommend staying at least 3 to 4 nights in order to enjoy the reserve.