African Music: a Sound of Dissent

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Vallejo News

Vallejo News August 2, 2019 | Issue #402 Vallejo Admirals August Events Sign-Up for other City The Vallejo Admirals will Communications play a total of 12 home games. The team will hold multiple special event nights, including, "Cal In This Issue Maritime Night," "Salute to Labor Night," and "Fan Vallejo Admirals August Events Appreciation Night." The first home game of the National Night Out month will be held on Iscah Uzza Foundation Inc. Cancer Awareness Friday, August 2, at Fundraiser Wilson Park. To view the schedule and purchase Six Flags Discovery Kingdom - Out at the tickets, click here. Kingdom Annual Planning Meeting Topic: Lake National Night Out - August 6 Dalwigk Vallejo Soup National Night Out VCAF Gala Fundraiser will take place in multiple locations Fifth Annual Social Justice in Public Health on Tuesday, Lecture Series August 6, from Empress Theatre Events 6:00 p.m. to 8:30 p.m. National Night Art Show Debut out is an annual community-building Poetry by the Bay campaign that Children's Wonderland Events helps promote police community McCune Collection Graphic Arts Group partnership and neighborhood Vallejo Food & Art Walk, August 9 camaraderie to make Vallejo a safer, more caring place to live. National Kids n Film Workshop Night Out strengthens the relationship between law enforcement and neighbors and aids in the sense of true community. It provides a great Paint Night opportunity to bring the residents of Vallejo and the police department together under positive circumstances. McCune Collection Summer Event Madame Butterfly For more information on hosting a National Night Out in your Vallejo neighborhood, e-mail [email protected]. -

Lightning in a Bottle

LIGHTNING IN A BOTTLE A Sony Pictures Classics Release 106 minutes EAST COAST: WEST COAST: EXHIBITOR CONTACTS: FALCO INK BLOCK-KORENBROT SONY PICTURES CLASSICS STEVE BEEMAN LEE GINSBERG CARMELO PIRRONE 850 SEVENTH AVENUE, 8271 MELROSE AVENUE, ANGELA GRESHAM SUITE 1005 SUITE 200 550 MADISON AVENUE, NEW YORK, NY 10024 LOS ANGELES, CA 90046 8TH FLOOR PHONE: (212) 445-7100 PHONE: (323) 655-0593 NEW YORK, NY 10022 FAX: (212) 445-0623 FAX: (323) 655-7302 PHONE: (212) 833-8833 FAX: (212) 833-8844 Visit the Sony Pictures Classics Internet site at: http:/www.sonyclassics.com 1 Volkswagen of America presents A Vulcan Production in Association with Cappa Productions & Jigsaw Productions Director of Photography – Lisa Rinzler Edited by – Bob Eisenhardt and Keith Salmon Musical Director – Steve Jordan Co-Producer - Richard Hutton Executive Producer - Martin Scorsese Executive Producers - Paul G. Allen and Jody Patton Producer- Jack Gulick Producer - Margaret Bodde Produced by Alex Gibney Directed by Antoine Fuqua Old or new, mainstream or underground, music is in our veins. Always has been, always will be. Whether it was a VW Bug on its way to Woodstock or a VW Bus road-tripping to one of the very first blues festivals. So here's to that spirit of nostalgia, and the soul of the blues. We're proud to sponsor of LIGHTNING IN A BOTTLE. Stay tuned. Drivers Wanted. A Presentation of Vulcan Productions The Blues Music Foundation Dolby Digital Columbia Records Legacy Recordings Soundtrack album available on Columbia Records/Legacy Recordings/Sony Music Soundtrax Copyright © 2004 Blues Music Foundation, All Rights Reserved. -

OBHOF INDUCTEES Why We Honor Them 2104

OBHOF INDUCTEES 2104 Why We HonorThem: Dr. Harold Aldridge March 3, 2014 Aldridge sings the blues Dr. Harold Aldridge is a retired professor of psychology at NSU in Tahlequah. Tahlequah Daily Press By RENEE FITE Special Writer TAHLEQUAH — The gray is beginning to cover his once-black hair, and it shows when the tall, lanky musician adjusts his black felt cowboy hat. He’s admits to being a little nervous. To keep his hands busy and mind occupied before the show begins, he tunes his guitar, glancing around the room, waving or nodding to friends. “An Evening of Blues Music,” presented at Webb Tower by Dr. Harold Aldridge, professor emeritus of psychology at Northeastern State University, was in observance of Black History month. After a brief introduction and enthusiastic applause, Aldridge began with a joke. “As the milk cow said to the dairy man, ‘Thanks for the warm hand,’” he said. For the next hour, the audience was taken on a journey through black history via the blues, from deep in the Mississippi Delta, to Alabama, the East Coast, Kansas City, Oklahoma, Texas and California. “I’m going to tell you the history of blues, and hopefully, it will be entertaining,” Aldridge said. “I stick with the old stuff, from Memphis, Mississippi, Alabama, and Tennessee.” According to Aldridge, blues music is evolving. “It’s almost like rock in some places; I guess next we’ll have rap blues,” he said. As his story unfolded, the audience learned the blues has changed with varying locations and situations. “The blues originated in West Africa and came here as a feeling, the soul of it, the spirit of high John the Conqueror,” said the Aldridge. -

American Folklife Center & Veterans History Project Annual Report for FY2008

AMERICAN FOLKLIFE CENTER & VETERANS HISTORY PROJECT Library of Congress Annual Report, Fiscal Year 2008 (October 2007-September 2008) The American Folklife Center (AFC), which includes the Veterans History Project (VHP), had another productive year. Over a quarter million items were acquired by the AFC Archive, which is the country’s first national archive of traditional life, and one of the oldest and largest of such repositories in the world. About 240,000 items were processed, and thus made available to researchers at the Library and beyond. In addition, the Center continued to expand programming through symposia, concerts, and public lectures; by providing field school training to universities and international organizations; and by providing technical assistance to individuals and groups. AFC also continued to be a leader in international discussions concerning traditional culture and intellectual property, and the AFC director served as a member of US delegations to meetings convened by the World Intellectual Property Organization (WIPO), UNESCO, and the Organization of American States (OAS). Both AFC and VHP provided substantial services to Congress. The Veterans History Project (VHP) continued making major strides in its mission to collect and preserve the stories of our nation's veterans, receiving upwards of 100 collections a week and acquiring over 22,000 items. The maturation of the Project was reflected by its partnership with WETA-TV and PBS in their presentation of the Ken Burns film, The War, which told the story of World War II through the memories of individual veterans from four American towns. VHP also continued to foster solid working relationships with a wide variety of project participants nationwide, including the U.S. -

Identification and Analysis of Wes Montgomery's Solo Phrases Used in 'West Coast Blues'

Identification and analysis of Wes Montgomery's solo phrases used in ‘West Coast Blues ’ Joshua Hindmarsh A Thesis submitted in fulfillment of requirements for the degree of Masters of Music (Performance) Sydney Conservatorium of Music The University of Sydney 2016 Declaration I, Joshua Hindmarsh hereby declare that this submission is my own work and that it contains no material previously published or written by another person except for the co-authored publication submitted and where acknowledged in the text. This thesis contains no material that has been accepted for the award of a higher degree. Signed: Date: 4/4/2016 Acknowledgments I wish to extend my sincere gratitude to the following people for their support and guidance: Mr Phillip Slater, Mr Craig Scott, Prof. Anna Reid, Mr Steve Brien, and Dr Helen Mitchell. Special acknowledgement and thanks must go to Dr Lyle Croyle and Dr Clare Mariskind for their guidance and help with editing this research. I am humbled by the knowledge of such great minds and the grand ideas that have been shared with me, without which this thesis would never be possible. Abstract The thesis investigates Wes Montgomery's improvisational style, with the aim of uncovering the inner workings of Montgomery's improvisational process, specifically his sequencing and placement of musical elements on a phrase by phrase basis. The material chosen for this project is Montgomery's composition 'West Coast Blues' , a tune that employs 3/4 meter and a variety of chordal backgrounds and moving key centers, and which is historically regarded as a breakthrough recording for modern jazz guitar. -

Fender Players Club Blues Bass

FENDER PLAYERS CLUB BLUES BASS TAGS & TURNAROUNDS A couple of features that have come into widespread use in playing the blues are "tags" and "turnarounds." TAGS A tag is simply a section, generally four bars, that’s repeated in order to prolong the blues, often to build excitement prior to the ending. In a live situation, tags can sometimes go on practically forever. Singers and instrumentalists alike use tags all the time. A typical performance (live or recorded) will adhere to the following sequence of events: 1. Introduction 2. Melody (played or sung) 3. Solos (generally the longest section, especially if it’s a large band) 4. Repetition of melody 5. Ending As a bass player, you need to be on your toes, watching (and listening!), especially after the reprise of the melody. If there is a tag, it’s going to be just before the ending. Sometimes there’s just no telling how long it will last. You need to be alert here, too, because you never know when the leader or singer will be ready to end the song. (Sometimes you may even wonder if they’ll ever be ready!) Here are a few tags to give you an idea of how they are used. The first four bars in each of the following selections represent the last four bars of a twelve-bar blues, in other words, measures 9-12. The tag section is played an indefinite number of times. See if you can get a friend to play the chords on guitar or keyboard so you can jam along. -

A Sampler of Blues Musicians and Styles, 1903 - 1964

Teacher’s Guide: THE BLUES - A SAMPLER OF BLUES MUSICIANS AND STYLES, 1903 - 1964 WITH ROBERT JONES B-5; 21:17 MIN At the end of the video, “The Blues - A Sampler of Significant Blues Musicians, 1903-1964” the students will be able to: Identify who is considered the Father of the Blues and explain why. Name two female blues artist important in the 1920s and explain why. Identify the world-known blues/ jazz musician from Davenport, Iowa who recorded the song “Davenport Blues. Explain what kind of blues music was considered City Blues. Identify great musicians who played City Blues and explain what they were known for. 2 THE BLUES – A SAMPLER OF BLUES MUSICIANS AND STYLES, 1903 – 1964 Video: Video: W.C. Handy because he discovered blues music being played Mamie Smith was the first female to record blues music in in the South, rather than inventing it. 1920. Bessie Smith dominated the blues music scene in the 1920s. 3 THE BLUES – A SAMPLER OF BLUES MUSICIANS AND STYLES, 1903 – 1964 Video: Blues music commonly played by a band that included an electric guitar. Video: Bix Beiderbecke who had a band that recorded under the name “Bix & His Rhythm Jugglers.” Video: T-Bone Walker was known as one of the greatest blues gui- tarists and singers. Muddy Waters was known equally well for Answers to Multiple Choice Quiz: his singing and playing and for his expertise at playing slide 1. C 2. D 3. A 4. B 5. D guitar. Big Mama Thornton, known for, among other things, an early recording of “Hound Dog.” 4 THE BLUES – A SAMPLER OF BLUES MUSICIANS AND STYLES, 1903 – 1964 Additional Learning, from Robert Jones Women in the Blues: Gertrude “Ma” Rainey (1886-1939) was the first blues singer to tour, which is why she is called the “Mother of the Blues.” Mamie Smith, by being the first blues artist to record, opened the door for the many artists that W.C. -

Essential Blues Discography

ESSENTIAL BLUES DISCOGRAPHY ESSENTIAL BLUES DISCOGRAPHY Edited by Francesco Piccolo First Edition July2015 Second Edition May 2016 Third Edition October 2016 Reference Book Francesco Piccolo - STORIA DEL BLUES - Gli Eventi, gli Stili, i Protagonisti Web Site www.thesixstrings.com This Book is available for free download at www.thesixstrings.com Contents 1 PREFACE .......................................................................................... 3 2 WORK SONGS, BALLADS, SPIRITUALS, MINSTREL SONGS ..... 5 3 COUNTRY BLUES ............................................................................ 7 4 CLASSIC BLUES ERA .................................................................... 13 5 URBAN BLUES ............................................................................... 15 6 RHYTHM AND BLUES, ROCK 'N' ROLL ,SOUL, FUNK ................ 25 7 ROCK BLUES ................................................................................. 33 1 PREFACE The following discography has no pretensions of completeness but just wants to be a guide providing suggestions to understand the various styles of Blues. For a more complete discography please refer to the discographies of individual artists, sites and specialized publications. 3 4 2 WORK SONGS, BALLADS, SPIRITUALS, MINSTREL SONGS BALLADS Ol'Riley Frankie and Albert "Ballad of John Henry Midnight Special SPIRITUALS Go down Moses Steal Away to Jeasus Nobody knows the trouble I've seen Deep River Swing Low, Sweet Chariot Shout for Joy Joshua Fit the Battle of Jerico The Great Camp -

A Brief History of the Blues

A Brief History Of The Blues By ED KOPP August 16, 2005 Sign in to view read count View All 1 2 Next » When you think of the blues, you think about misfortune, betrayal and regret. You lose your job, you get the blues. Your mate falls out of love with you, you get the blues. Your dog dies, you get the blues. While blues lyrics often deal with personal adversity, the music itself goes far beyond self-pity. The blues is also about overcoming hard luck, saying what you feel, ridding yourself of frustration, letting your hair down, and simply having fun. The best blues is visceral, cathartic, and starkly emotional. From unbridled joy to deep sadness, no form of music communicates more genuine emotion. The blues has deep roots in American history, particularly African- American history. The blues originated on Southern plantations in the 19th Century. Its inventors were slaves, ex-slaves and the descendants of slaves—African-American sharecroppers who sang as they toiled in the cotton and vegetable fields. It's generally accepted that the music evolved from African spirituals, African chants, work songs, field hollers, rural fife and drum music, revivalist hymns, and country dance music. The blues grew up in the Mississippi Delta just upriver from New Orleans, the birthplace of jazz. Blues and jazz have always influenced each other, and they still interact in countless ways today. Unlike jazz, the blues didn't spread out significantly from the South to the Midwest until the 1930s and '40s. Once the Delta blues made their way up the Mississippi to urban areas, the music evolved into electrified Chicago blues, other regional blues styles, and various jazz-blues hybrids. -

Al King & Arthur K Adams

AL KING & ARTHUR K ADAMS: Together – The Complete Kent and Modern Recordings Ace CDCHD 1292 (58:58) AL KING: My Name Is Misery/ Ain't Givin' Up Nothin'/ Better To Be By Yourself/ It's Getting Late/ The Thrill Is Gone/ Bad Understanding*/ The World Needs Love/ Lovin' You*/ I Still Care For You*/ Get Lost/ Without A Warning/ Maybe My Last Song*: ARTHUR K ADAMS: She Drives Me Out Of My Mind/ Gimme Some Of Your Lovin'/ I Need You/ I'm Lonely For You/ Let Your Hair Down/ You Make Me Cry*/ I Need You (alt)/ (& EDNA WRIGHT) Let's Get Together**/ (& MARY) Is That You** (* = previously unissued; ** = alternate take) This is a tale of two talented blues artists who arrived on the scene just a little too late. Well... in the case of Arthur K Adams it is, although in the case of Al King, getting to an influential label just a little too late is perhaps a more accurate description. Vocalist and Louisianan, Al Smith, born in 1926, located to the West Coast after WWII, first to Los Angeles and then to Oakland, where from 1951 through to the early sixties he had a number of single releases on small label enterprises. It wasn't until the mid sixties however before he had anything like a hit, and after he'd changed his nom de disque to Al King, this was with 'Think Twice Before You Speak', first issued on his own Flag imprint and then leased to the New York Sahara label (initially Sahara's owner, a record distributor, wanted copies of the Flag release, but when Al couldn't afford to have them pressed, he leased the tracks). -

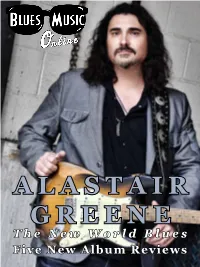

The New World Blues Five New Album Reviews Order Today Click Here! Four Print Issues Per Year

ALASTAIR GREENE The New World Blues Five New Album Reviews Order Today Click Here! Four Print Issues Per Year Every January, April, July, and October get the Best In Blues delivered right t0 you door! Artist Features, CD, DVD Reviews & Columns. Award-winning Journalism and Photography! Order Today ALASTAIR GREENE Click THE NEW WORLD BLUES Here! H NEW ALBUM H Produced by Tab Benoit for WHISKEY BAYOU RECORDS Available October 23, 2020 “Fronting a power blues-rock trio, guitarist Alastair Greene breathes in sulfuric fumes and exhales blazing fire.” - Frank John Hadley, Downbeat Magazine “Greene is a no frills rock vocalist. His fiery solos prove him a premier shredder who will appeal to fans of Walter Trout, Joe Bonamassa, and Albert Castiglia.” - Thomas J Cullen III, Blues Music Magazine “On THE NEW WORLD BLUES, Alastair makes it clear why he is a ‘guitar player’s guitar player,’ and this recording will surely leave the Alastair Greene stamp on the Blues Rock World.” - Rueben Williams, Thunderbird Management, Whiskey Bayou Records alastairgreene.com whiskeybayourecords.com BLUES MUSIC ONLINE November 11, 2020 - Issue 21 Table Of Contents 06 - ALASTAIR GREENE The New World Blues By Art Tipaldi & Jack Sullivan 18 - FIVE NEW CD REVIEWS By Various Writers 28 - FIVE BOOK REVIEWS 39 - BLUES MUSIC SAMPLER DOWNLOAD CD Sampler 26 - July 2020 PHOTOGRAPHY © LAURA CARBONE COVER PHOTOGRAPHY © COURTESY ALASTAIR GREENE Read The News Click Here! All Blues, All The Time, AND It's FREE! Get Your Paper Here! Read the REAL NEWS you care about: Blues Music News! -

Acts Include

www.swanage-blues.org 2008 2009 Past Home October March Swanage ACCOMMODATION Contact Festivals Festival Festival The Eighth Swanage Blues Festival 7, 8, 9 March 2008 ADMISSION POLICY Admission is free to customers at all venues, except restaurants where conditions apply. OFFICIAL COLLECTIONS The festival is organised by Steve Darrington, a disabled musician who gave up touring due to an accident. He organises the festival at his own expense. So please give as much as possible when the Official Collectors come round, so he can afford to do it again! Friends of the Festival write: This festival is organised by Steve z ARTISTS and Advertisers Darrington, a touring z Schedule of Events musician all his life until ill health took him z Programme (download) off the road. z Poster (download) He organises the z festival at his own expense. Get on the Mailing List for latest info! click here Please help him to keep it going with donations and advertising, see here. Acts include The Guv'nors Debbie Giles Band Will Killeen BEAT THOSE Jon Walsh Blues Band Ernie's Rhythm Section Sonny Black WASHDAY Angelina & JC Storm Warning Hightown Crows BLUES! Grimshaw with Harris, Budden & Motel 6 John Crampton PURBECK VALET Osborne 73 High St, Swanage Robert Hokum Blues The Mustangs Robin Bibi DRY CLEANING Band SERVICE WASH The Ragtime Jug Coalhouse Walker Chris Collins & Blues Etc free collection and delivery Orchestra 01929 424900 Coast Steve Darrington C Sharp Blues plus some Sorbet for the Blues Palate! Fabulous Fezheads and Kellys Tattoo not forgetting OPEN MIC with Andrew Bazeley and Martin Froud plus Blues Steam Train ride and more! SCHEDULE OF EVENTS here THE GUV'NORS Saturday evening 10pm - White Horse The Guv'nors 20th Year Tour continues! Led by Bluesmaster Robert Hokum on guitar and vocals, this seven piece outfit plays the blues with psychedelic funk, acid jazz and Latin grooves.