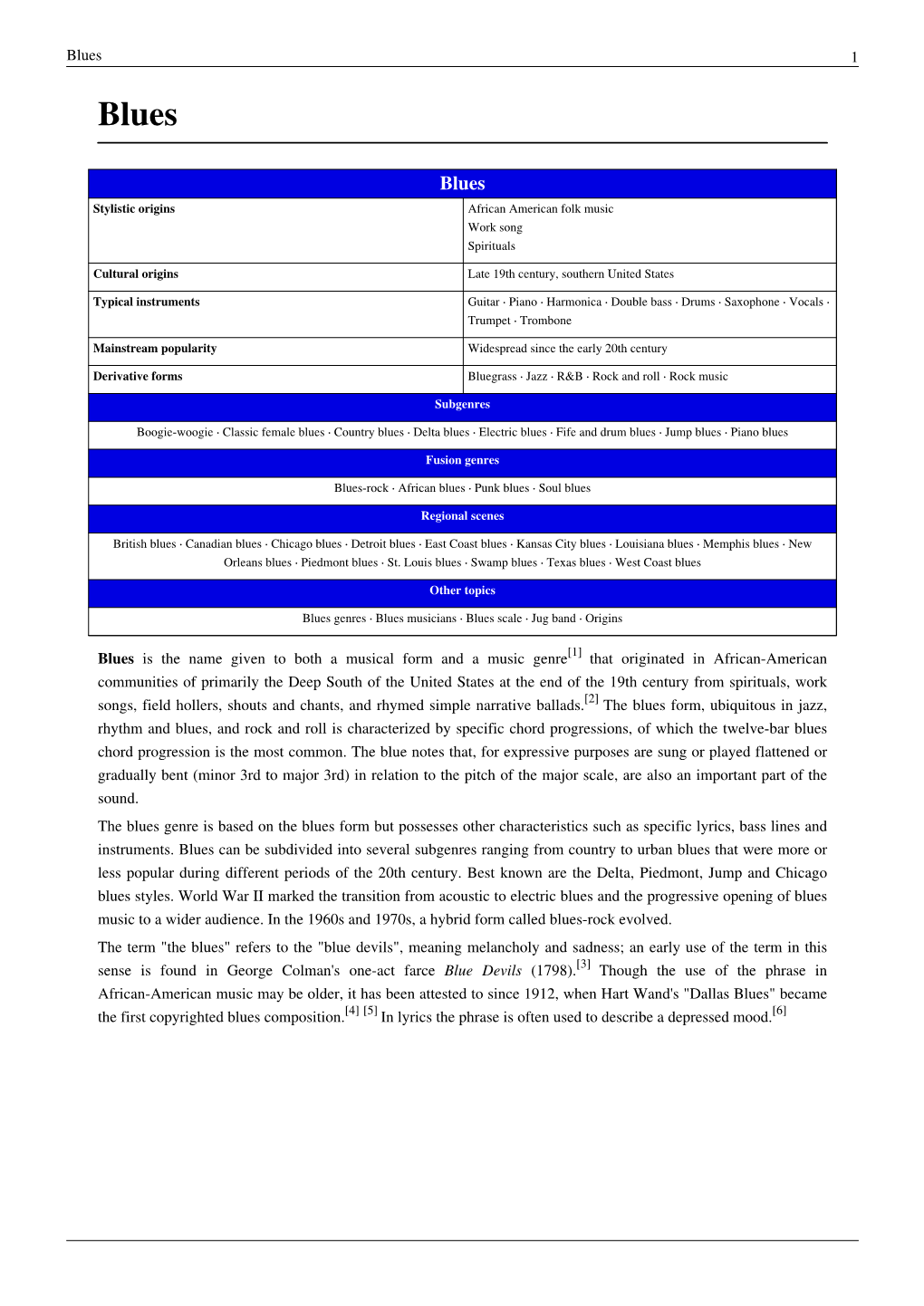

Blues 1 Blues

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Five Guys Named Moe Sassy Tributesassy to Louis Jordan,Singer, Songwriter, Bandleader and Rhythm and Blues Pioneer

AUDIENCE GUIDE 2018 - 2019 | Our 59th Season | Issue 3 Issue | Season 59th Our 2019 | A musical by Clarke Peters Featuring Louis Jordan’s greatest hits Five Guys Named Moe is a jazzy, Ch’ Boogie, Let the Good Times Roll sassy tribute to Louis Jordan, singer, and Is You Is or Is You Ain’t My Baby?. songwriter, bandleader and rhythm and “Audiences love Five Guys because Season Sponsors blues pioneer. Jordan was in his Jordan’s music is joyful and human, heyday in the 1940s and 50s and his and takes you on an emotional new slant on jazz paved the way for rollercoaster from laughter to rock and roll. heartbreak,” said Skylight Stage Five Guys Named Moe was originally Director Malkia Stampley. produced in London's West End, “Five Guys is, of course, all about guys. winning the Laurence Olivier Award for But it is also a true ensemble piece and Best Entertainment; when it moved to the Skylight is proud to support our Broadway in 1992, it was nominated for talented performers with a strong two Tony Awards. creative team of women rocking the The party begins when we meet our show from behind the scenes.” Research/Writing by hero Nomax. He's broke, his girlfriend, Justine Leonard for ENLIGHTEN, The Los Angeles Times called Five Skylight Music Theatre’s Lorraine, has left him and he is Guys Named Moe “A big party with… Education Program listening to the radio at five o'clock in enough high spirits to send a small Edited by Ray Jivoff the morning, drinking away his sorrows. -

Queen of the Blues © Photos AP/Wideworld 46 D INAHJ ULY 2001W EASHINGTONNGLISH T EACHING F ORUM 03-0105 ETF 46 56 2/13/03 2:15 PM Page 47

03-0105_ETF_46_56 2/13/03 2:15 PM Page 46 J Queen of the Blues © Photos AP/WideWorld 46 D INAHJ ULY 2001W EASHINGTONNGLISH T EACHING F ORUM 03-0105_ETF_46_56 2/13/03 2:15 PM Page 47 thethe by Kent S. Markle RedRed HotHot BluesBlues AZZ MUSIC HAS OFTEN BEEN CALLED THE ONLY ART FORM J to originate in the United States, yet blues music arose right beside jazz. In fact, the two styles have many parallels. Both were created by African- Americans in the southern United States in the latter part of the 19th century and spread from there in the early decades of the 20th century; both contain the sad sounding “blue note,” which is the bending of a particular note a quar- ter or half tone; and both feature syncopation and improvisation. Blues and jazz have had huge influences on American popular music. In fact, many key elements we hear in pop, soul, rhythm and blues, and rock and roll (opposite) Dinah Washington have their beginnings in blues music. A careful study of the blues can contribute © AP/WideWorld Photos to a greater understanding of these other musical genres. Though never the Born in 1924 as Ruth Lee Jones, she took the stage name Dinah Washington and was later known leader in music sales, blues music has retained a significant presence, not only in as the “Queen of the Blues.” She began with singing gospel music concerts and festivals throughout the United States but also in our daily lives. in Chicago and was later famous for her ability to sing any style Nowadays, we can hear the sound of the blues in unexpected places, from the music with a brilliant sense of tim- ing and drama and perfect enun- warm warble of an amplified harmonica on a television commercial to the sad ciation. -

April 2019 BLUESLETTER Washington Blues Society in This Issue

LETTER FROM THE PRESIDENT Hi Blues Fans, The final ballots for the 2019 WASHINGTON BLUES SOCIETY Best of the Blues (“BB Awards”) Proud Recipient of a 2009 of the Washington Blues Society are due in to us by April 9th! You Keeping the Blues Alive Award can mail them in, email them OFFICERS from the email address associ- President, Tony Frederickson [email protected] ated with your membership, or maybe even better yet, turn Vice President, Rick Bowen [email protected] them in at the April Blues Bash Secretary, Open [email protected] (Remember it’s free!) at Collec- Treasurer, Ray Kurth [email protected] tor’s Choice in Snohomish! This Editor, Eric Steiner [email protected] is one of the perks of Washing- ton Blues Society membership. DIRECTORS You get to express your opinion Music Director, Amy Sassenberg [email protected] on the Best of the Blues Awards Membership, Open [email protected] nomination and voting ballots! Education, Open [email protected] Please make plans to attend the Volunteers, Rhea Rolfe [email protected] BB Awards show and after party Merchandise, Tony Frederickson [email protected] this month. Your Music Director Amy Sassenburg and Vice President Advertising, Open [email protected] Rick Bowen are busy working behind the scenes putting the show to- gether. I have heard some of their ideas and it will be a stellar show and THANKS TO THE WASHINGTON BLUES SOCIETY 2017 STREET TEAM exceptional party! True Tone Audio will provide state-of-the-art sound, Downtown Seattle, Tim & Michelle -

PTSVNWU JS-5 Jam Station Style Listing

PTSVNWU JS-5 Jam Station Style Listing ROCK 1 POP BLUES JAZZ 01 JS-5HardRock 11 ElectricRock 01 Shuffle 1 01 ChicagoBlues 01 DublTimeFeel 02 BritHardRck1 12 Grunge 02 Shuffle 2 02 OrganBlues 02 Organ Jazz 03 BritHardRck2 13 Speedy Rock 03 Mid Shuffle 03 ShuffleBlues 03 5/4 Jazz 04 80'sHardRock 14 Funk Rock 04 Simple8btPop 04 Boogie 04 Latin Jazz 05 Fast Boogie 15 Glam Rock 05 70's Pop 05 Rockin'Blues 05 Soul Jazz 06 Heavy & Loud 16 Funk Groove 06 Early80'sPop 06 RckBeatBlues 06 Swing Jazz 1 07 Slow Rock 1 17 Spacy Rock 07 Dance Pop 07 Medium Blues 07 Swing Jazz 2 08 Slow Rock 2 18 Progressive 08 Synth Pop 08 Funky Blues 08 Swing 6/8 09 Slow & Heavy 09 Honky Piano 09 Jump Blues 09 BigBandJazz 10 Hyper Metal ROCK 3 10 Slow Pop 10 BluesInMinor 10 Combo Jazz 11 Old HvyMetal 11 Reggae Pop 11 Blues Brass 11 Modern Jazz 12 Speed Metal 01 AcousticRck1 12 Rockabilly 12 AcGtr Boogie 12 Jazz 6/8 13 HvySlowShffl 02 AcousticRck2 13 Surf Rock 13 Gospel Shout 13 Jazz Waltz 14 MidFastHR 1 03 Gtr Arpeggio 14 8thNoteFeel1 14 Jazz Ballad 15 MidFastHR 2 04 CntmpraryRck 15 8thNoteFeel2 R&B 16 80sHeavyMetl 05 8bt Rock 1 16 16thNoteFeel FUSION 17 ShffleHrdRck 06 8bt Rock 2 01 RhythmGtrFnk 18 FastHardRock 07 8bt Rock 3 BALLAD 02 Brass Funk 01 Power Fusion 19 HvyFunkRock 08 16bt Rock 03 Psyche-Funk 02 Smooth Jazz 09 5/4 Rock 01 NewAgeBallad 04 Cajun Funk 03 Wave Shuffle ROCK 2 10 Shuffle Rock 02 PianoBallad1 05 Funky Soul 1 04 Super Funk 11 Fusion Rock 03 PianoBallad2 06 Funky Soul 2 05 Crossover 01 90sGrooveRck 12 Sweet Sound 04 E.PianoBalad 07 60's Soul 06 -

“ Blues Ain't Football. You Don't Have to Retire at 30. You Can Grow and Play

LOCALS | BY PHIL RESER | PHOTOS: ERIC LESLIE “ Blues ain’t football. You don’t have to retire at 30. You can grow and play all your life.” —Elvin Bishop THE LIFE AND LEGEND OF LESLIE ‘LAZY LESTER’ JOHNSON UP ON THE RIDGE in Paradise lives a blues music legend La., that fate turned his way. He recognized a guy named named Leslie ‘Lazy Lester’ Johnson, originally from South Lightnin’ Slim, a recording artist who was riding on the same Louisiana, where he built his legendary music career as one bus, headed to Crowley to cut a record at Jay Miller’s Studio, of the key creators of the swamp blues sound in the ‘50s. where much of the material for the Nashville-based Excello Lester crafted a style as unique as his nickname. It’s a Records was being recorded. mixture of blues, swamp pop and classic country. After establishing a friendly connection with Slim, Lester Born in Torras, La., in 1933 and raised outside of Baton decided to stay on the bus and accompany him to the studio. Rouge, he became a harp player and vocalist. When they got there, the scheduled harp player, Wild Bill As a boy, he worked as a gas station attendant, woodcutter Phillips, had not showed up for the session work. Lester told and at a grocery store, saving money to purchase a harmonica Slim he thought he could handle the harp parts. Remarkably, and Little Walter’s “Juke” record. Slim and Miller gave him his big chance, and that was the Then Lester began to blow that harp, and at the same time, moment that Lester became a mainstay on Slim’s Excello he borrowed his brother’s guitar and learned how to strum recordings and his live shows. -

Episode 2 - Agenda Made 20140822

Episode 2 - Agenda Made 20140822 Intro Welcome to Point Radio Cast. Contact Info [email protected] Links to music on pointradiocast.com Click through the site to buy it, and support us and the bands. Show intro - Theme Best CDs I currently own, part one. If on a deserted island with a CD player and a solar power source, which CDs would I want to have? 2 songs from each disc. This will be a 2 part episode. Chronological order. The Misfits - Static Age Recorded 1978. Loved by millions. Classic and great. Some Kinda Hate Last Caress Minor Threat - Complete Discography. Recorded between 1981-1983. Godfathers of straight edge hardcore. Odd for me, but awesome and raw. Filler Out of Step The Pogues - The Best of the Pogues Recorded between 1984-1991. Dog through painting on cover. Godfathers of punk edge irish. Many bands spring from them, like the Tossers, Flogging Molly, anything of that ilk. Fairytale of New York Streams of Whiskey Guns N Roses - Appetite for Destruction Release 1987. A bit mainstream, but awesome. Nuff said. It's So Easy My Michelle Sloppy Seconds - Destroyed Released 1989. Classic bad attitude obnoxious midwest punk rock. Black Mail Steal your Beer Mid-show Interruption Can we fuck off with the ice bucket shit? Remember when people did their share without needing recognition for it from the world? Fuck ALS, it sucks. All the toolbox ice bucket bullshit sucks too. Try and do your part without needing a pat on the back from all your FB friends. Bad Religion - Against the Grain Released 1990. -

5, 2015 •Marina Park, Thunder

14TH ANNUAL BLUESFEST Your free festival program courtesy of your friends at The Chronicle-Journal JOHNNY REID • JULY 3 - 5, 2015 JULY • MARINA PARK, THUNDER BAY KENNY WAYNE SHEPHERD BAND PAUL RODGERS JOHNNY REID • ALAN FREW • THE PAUL DESLAURIERS BAND • THE BOARDROOM GYPSIES • KENNY WAYNE SHEPHERD BAND • ALAN DOYLE • THE WALKERVILLES • KELLY RICHEY • BROTHER YUSEF • THE BRANDON NIEDERAUER BAND • THE GROOVE MERCHANTS • LOOSE CANNON• PAUL RODGERS • DOYLE BRAMHALL II • WALTER TROUT • THE SHEEPDOGS • THE BROS. LANDRETH • JORDAN JOHN • THE HARPOONIST AND THE AXE MURDERER • THE KRAZY KENNY PROJECT THE VOICE... KEN WRIGHT rock guitar for more than two decades, Kenny Wayne SPECIAL TO THE CHRONICLE-JOURNAL Shepherd will hot wire the marquee on Saturday. Not to be missed, Paul Rogers, the peerless, 90-million-record-sell- What is it about a blues festival, that antsy sense of ing, oh-so-soulful voice of authoritative bands Free, Bad anticipation that we feel? It's a given that the music and Company and Queen will close the festival with the ulti- Ken Wright its performers will be royally entertaining. Yet, we all arrive mate in front man style and swagger on Sunday. with fingers crossed, hoping for that transcendent experi- Newfoundland's unstoppable native son, Alan Doyle, will Has the blues, but in a good way. He writes about them. A veteran director of ence that will reverse the spin of our world if only for an introduce East Coast reels to Top 40 pop with mandolins, fiddles and bouzoukis. Considered by Eric Clapton to be the Thunder Bay Blues Society, Wright puts his writing ability together with an hour to be relived again and again with all who shared it. -

San Antonio's West Side Sound

Olsen: San Antonio's West Side Sound San Antonio’s SideSound West Antonio’s San West Side Sound The West Side Sound is a remarkable they all played an important role in shaping this genre, Allen O. Olsen amalgamation of different ethnic beginning as early as the 1950s. Charlie Alvarado, Armando musical influences found in and around Almendarez (better known as Mando Cavallero), Frank San Antonio in South-Central Texas. It Rodarte, Sonny Ace, Clifford Scott, and Vernon “Spot” Barnett includes blues, conjunto, country, all contributed to the creation of the West Side Sound in one rhythm and blues, polka, swamp pop, way or another. Alvarado’s band, Charlie and the Jives, had such rock and roll, and other seemingly regional hits in 1959 as “For the Rest of My Life” and “My disparate styles. All of these have Angel of Love.” Cavallero had an influential conjunto group somehow been woven together into a called San Antonio Allegre that played live every Sunday sound that has captured the attention of morning on Radio KIWW.5 fans worldwide. In a sense, the very Almendarez formed several groups, including the popular eclectic nature of the West Side Sound rock and roll band Mando and the Chili Peppers. Rodarte led reflects the larger musical environment a group called the Del Kings, which formed in San Antonio of Texas, in which a number of ethnic during the late 1950s, and brought the West Side Sound to Las communities over the centuries have Vegas as the house band for the Sahara Club, where they exchanged musical traditions in a remained for nearly ten years.6 Sonny Ace had a number of prolific “cross-pollination” of cultures. -

Chasing the Echoes in Search of John Lee Hooker’S Detroit by Jeff Samoray

Chasing the Echoes In search of John Lee Hooker’s Detroit by jeff samoray n September of 1948, John Lee Hooker strummed the chord bars, restaurants, shoeshine parlors and other businesses that made up that ignited the endless boogie. Like many Delta blues musicians the neighborhood — to make way for the Chrysler Freeway. The spot I of that time, Hooker had moved north to pursue his music, and he where Hooker’s home once stood is now an empty, weed-choked lot. was paying the bills through factory work. For five years he had been Sensation, Fortune and the other record companies that issued some of toiling as a janitor in Detroit auto and steel plants. In the evenings, he Hooker’s earliest 78s have long been out of business. Most of the musi- would exchange his mop and broom for an Epiphone Zephyr to play cians who were on the scene in Hooker’s heyday have died. rent parties and clubs throughout Black Bottom, Detroit’s thriving Hooker left Detroit for San Francisco in 1970, and he continued black community on the near east side. “doin’ the boogie” until he died in 2001, at age 83. An array of musi- Word had gotten out about Hooker’s performances — a distinct, cians — from Eric Clapton and Bonnie Raitt to the Cowboy Junkies primitive form of Delta blues mixed with a driving electric rhythm. and Laughing Hyenas — have covered his songs, yet, for all the art- After recording a handful of crude demos, he finally got his break. ists who have followed in Hooker’s footsteps musically, it’s not easy to Hooker was entering Detroit’s United Sound Systems to lay down his retrace his path physically in present-day Detroit. -

Bargain Blues

100% unofficial newsletter for P&O Blues Cruises Bargain Blues – book now! Those of you who keep a close eye on our ‘Blues@Sea’ Facebook Page will be aware that last month there was a sudden, unannounced, increase by P&O in the price of the November Blues Revue. This decision was reversed with the alert that the £99 price may well increase on Tuesday 19th September. DON’T DELAY!!!! Phone 0800 130 0030 (Currently there are almost 250 ‘cruisers’ signed up) 5-4-3-2-1 (Countdown for Kaz) For many years it’s been the ultimate accolade for UK blues artists to appear on the Paul Jones BBC Radio 2 Blues Show. In this edition (which focusses primarily on the great ‘Swamp Blues’ harpist Slim Harpo) a Kaz Hawkins track is featured. Kaz is at the start of her final tour with this fabulous multi-national band – ‘Cruisers’, of course, get two ‘bites at the cherry’ in November. This programme is well worth a listen - http://www.bbc.co.uk/programmes/b09039ny Ciao! Perhaps the least well known ‘Blues Revue’ act (to UK fans at least) is Veronica Sbergia & Max De Bernardi (Italy)…but that’s about to change. They swept to victory in the 2013 European Blues Challenge (as ‘The Red Wine Serenaders) and since then have performed across the Continent with their country blues and ragtime, hokum, jug band and rural music from the 20’s and 30’s. Veronica and Max who use strictly acoustic instruments such ukulele, washboard, kazoo and resophonic guitars, are terrific musicians and a lot-of-fun! Check-them-out on this video - https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=nj1rWJBuUJI Out of the studio into the Spinning Top! Norman Beaker and his band seem to be constantly on the road …particularly on Mainland Europe. -

2016 Regular Session ENROLLED SENATE RESOLUTION NO. 38 BY

2016 Regular Session ENROLLED SENATE RESOLUTION NO. 38 BY SENATOR CLAITOR A RESOLUTION To commend and congratulate the Baton Rouge Blues Foundation for its efforts to preserve and promote the unique blues culture of Baton Rouge and the region and to recognize the Baton Rouge Blues Festival being held on Saturday, April 9 through Sunday, April 10, 2016. WHEREAS, on the Mighty Mississippi, located between the urbane sophistication of New Orleans jazz and the Cajun and Zydeco sounds of the French people of Acadiana, is the Blues from Baton Rouge; and WHEREAS, it is a sound that draws from the experience of sharecroppers, cane cutters, plant workers and touring musicians; it is country come to town; it can be mysterious, even dark, but always full of life and energy; it is downhome and it is electric; it is the music of Lonesome, Lightnin', Lazy and Slim that captured the imagination of The Stones, The Kinks, The Moody Blues and the Black Keys; it is a spirit that lives on through the Blues families like Hogan, Thomas and Neal and still fuels the good times of many a local on a Saturday night - it is the Swamp Blues; and WHEREAS, the Baton Rouge Blues Foundation seeks to preserve, promote, and propel this unique blues culture of Baton Rouge and the region; and WHEREAS, this, 501(c)(3), not for profit organization, formed in 2002, is run entirely by volunteers who see the Swamp Blues as an asset to the communities of Baton Rouge and Louisiana as well as a beautiful and rich export to the nation and world; and WHEREAS, while native musical culture -

Has There Ever, in the History of 20Th Century Music, Ever Been a More Influential Organisation Than That of the American Folk Blues Festivals (AFBF)?

Muddy Waters John Lee Hooker Sonny Boy Williamson Willie Dixon, Buddy Guy Otis Spann a.m.m. ACT 6000-2 Release Date: 24. May 2004 Has there ever, in the history of 20th century music, ever been a more influential organisation than that of the American Folk Blues Festivals (AFBF)? Founded in 1962, this series has surely had a lasting effect on the European, American, and indeed interational, music scenes. Where would hip hop, jazz, funk, rock, heavy metal or world music be without the blues? Blues is the foundation of the popular music of the 20th century. Its intensity, rhythms and harmonies have affected many peoples and culture, up to and including the music of Africa, the alkand and Spanish flamenco. The blues captures the sentiments of the people in a nutshell. Of course, in the beginning it was just a feeling. But not just of the blues, but also of emptiness. The idea of tracking down and bringing surviving blues legends to Europe was that of jazz publicist Joachim Ernst Berendt at the end of the 1950s. The new style of rock 'n' roll was beginning to take a foothold, jazz was in the mean time beginning to be celebrated in Europe, but all too little was heard of the blues, despite itself being the musical foundation of jazz and rock 'n' roll. It was up to Horst Lippmann and his partner Fritz Rau to realise the idea of the AFBF and bring the best Afro- american blues performers to concert halls (!) for a European audience. First they contacted Willie Dixon.