The Chief Inspector's Report for Drinking Water in England

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Water Efficiency and the Water Companies a 2010 UK Review Contents

Water Efficiency and the Water Companies a 2010 UK Review Contents 01 Foreword 02 Supportive Quotes from Ministers, Water UK and Regulators 05 Part 1: Introduction and overview of water efficiency initiatives 06 Introduction 08 1.1 Direct activities of water companies to engage with all sectors 08 Engaging through online activities 08 Communicating to domestic customers 09 Working closely with non-domestic customers 09 Providing a range of water-efficient products 10 Promoting water efficiency outdoors 10 Communicating with schools and other groups 11 Working with the public sector – schools, hospitals and local councils etc 12 1.2 Working in partnership to deliver joint water efficiency campaigns 12 Waterwise 13 Waterwise East 13 Tap into Savings 14 Waterwise and Energy Saving Trust’s Regional Environmental Networks for Energy and Water (RENEW) project 14 Joint communications campaigns 15 The Water School website 15 South East Communications Group (formerly South-East Drought Communications Group) 16 1.3 Networks to learn and share information on water efficiency 16 Water Saving Group 16 Saving Water in Scotland 17 National Water Conservation Group 17 Water Efficiency Network 17 Watersave Network 18 1.4 Evidence Base for Large-Scale Water Efficiency in Homes 20 Water company areas 21 Part 2: Water company water efficiency highlights and case studies 22 Introduction 23 Anglian Water 23 Bournemouth and West Hampshire Water 24 Bristol Water 24 Cambridge Water 25 Dee Valley Water 25 Essex and Suffolk Water 26 Northern Ireland Water 26 Northumbrian -

Free Reservoir Walks

F R E E re S er VOI R WALKS RESERVOIR WALKS TO BLOW AWAY THE COBWEBS BROUGht TO YOU by ONly AVAIlable IN YORKSHIRE. WE LOOK AFTER 72,000 ACRES OF LAND IN YORKSHIRE, SPANNING THE NORTH YORK MOORS, THE WOLDS, AREAS OF OUTSTANDING NATURAL BEAUTY AND SOME OF THE BEST NATIONAL PARKS IN THE COUNTRY. AND ALL THIS IS FREE FOR YOU TO ENJOY. Here’s a TASTER OF SOME OF OUR FREE RESERVOIR WALKS... VISIT OUR WEBSITE FOR MORE WALKS YORKSHIREWATER.COM/RECREATION OUR walk DIFFICUlty ratINGS In this pack you’ll find directions to the site, a summary of the walk, a list of facilities available, a detailed route map and route instructions. These walks are easy to complete and do not require special footwear. Most of the walks are suitable for wheelchairs and pushchairs. These walks are mainly flat and on surfaced paths, however they can become muddy in wet weather. These walks include rough terrain and steeper gradients, making them unsuitable for young children and the infirm. These walks are for the experienced rambler, are at high altitudes and require good compass reading skills. Walking boots, food and drink and appropriate clothing and waterproofs are essential. Podcasts are available for walks featuring this symbol, just visit the recreation section on the Yorkshire Water website and click on the podcast link. Visit the easy access page for a choice of more walks, all of which are suitable for wheelchairs and pushchairs. Great care has been taken to ensure that the information in our activity packs (or other information made available) is accurate. -

South West River Basin District Flood Risk Management Plan 2015 to 2021 Habitats Regulation Assessment

South West river basin district Flood Risk Management Plan 2015 to 2021 Habitats Regulation Assessment March 2016 Executive summary The Flood Risk Management Plan (FRMP) for the South West River Basin District (RBD) provides an overview of the range of flood risks from different sources across the 9 catchments of the RBD. The RBD catchments are defined in the River Basin Management Plan (RBMP) and based on the natural configuration of bodies of water (rivers, estuaries, lakes etc.). The FRMP provides a range of objectives and programmes of measures identified to address risks from all flood sources. These are drawn from the many risk management authority plans already in place but also include a range of further strategic developments for the FRMP ‘cycle’ period of 2015 to 2021. The total numbers of measures for the South West RBD FRMP are reported under the following types of flood management action: Types of flood management measures % of RBD measures Prevention – e.g. land use policy, relocating people at risk etc. 21 % Protection – e.g. various forms of asset or property-based protection 54% Preparedness – e.g. awareness raising, forecasting and warnings 21% Recovery and review – e.g. the ‘after care’ from flood events 1% Other – any actions not able to be categorised yet 3% The purpose of the HRA is to report on the likely effects of the FRMP on the network of sites that are internationally designated for nature conservation (European sites), and the HRA has been carried out at the level of detail of the plan. Many measures do not have any expected physical effects on the ground, and have been screened out of consideration including most of the measures under the categories of Prevention, Preparedness, Recovery and Review. -

Recreation 2020-21

Conservation access and recreation 2020-21 wessexwater.co.uk Contents About Wessex Water 1 Our commitment 2 Our duties 2 Our land 3 Delivering our duties 3 Conservation land management 4 A catchment-based approach 10 Engineering and sustainable delivery 12 Eel improvements 13 Invasive non-native species 14 Access and recreation 15 Fishing 17 Partners Programme 18 Water Force 21 Photo: Henley Spiers Henley Photo: Beaver dam – see 'Nature’s engineers' page 7 About Wessex Water Wessex Water is one of 10 regional water and sewerage companies in England and About 80% of the water we supply comes from groundwater sources in Wiltshire Wales. We provide sewerage services to an area of the south west of England that and Dorset. The remaining 20% comes from surface water reservoirs which are includes Dorset, Somerset, Bristol, most of Wiltshire, and parts of Gloucestershire, filled by rainfall and runoff from the catchment. We work in partnership with Hampshire and Devon. Within our region, Bristol Water, Bournemouth Water and organisations and individuals across our region to protect and restore the water Cholderton and District Water Company also supply customers with water. environment as a part of the catchment based approach (CaBA). We work with all the catchment partnerships in the region and host two catchment partnerships, Bristol What area does Wessex Water cover? Avon and Poole Harbour, and co-host the Stour catchment initiative with the Dorset Wildlife Trust. our region our catchments Stroud 8 Cotswold South Gloucestershire Bristol Wessex -

York Association Newsletter

DATES FOR YOUR DIARY York Association MARCH Newsletter 10 Short Walk: Heslington 20 Social Evening and Quiz 25 Drop-in-lunch, Walmgate Ale House from 12 noon 28 AGM and lunch at the York Hilton from 10.30am APRIL 16 Short Walk: Strensall 28 Oldest Sweetshop event, St Edward’s, Dringhouses 2.30pm 29 Drop-in lunch, Walmgate Ale House & Bistro from 12 noon MAY 5 Short Walk: Skipwith Common 7-15 Holiday: Prague 16 Full-day walk: Gargrave 27 Drop-in lunch, Walmgate Ale House & Bistro from 12 noon JUNE 13 Full-Day walk: Hackfall Woods from Masham 23 Short Walk: Roman Road from Copmanthorpe 24 Drop-in lunch, Walmgate Ale House & Bistro from 12 noon An Association of National rusT t Members and Supporters Please send contributions and photographs for the June Newsletter to Catherine Brophy [email protected] by Wednesday 6th May Please save contributions in WORD format. Thank you. March Number 192 Printed by Print Solutions, Audax Close, Clifton Moor, York, YO30 4RA. (01904 690090) Contents Holiday Reviews Page A WINTER TRIP TO THE LAKE DISTRICT What’s On 3 Membership 4 On 5th Talks 4 December a group of YANT members set out for an overnight visit to AGM and Website Information 5 the Lake District. On the way we stopped for coffee at Mainsgill Farm, East Note from the Chair 6 Layton and some of us enjoyed the wonderful cakes and scones with our Social and Fundraising Events 7 coffee, and looking at the Christmas decorations to be bought. We also saw Holidays 8 the Camels, Llamas and Pigs which are kept in the surrounding fields. -

Bolton Abbey Station Road

WALKERS ARE WELCOME Embsay Railway Station To Leaving Embsay Station turn right along the main Follow the path across a farm track and through 3 Bolton Abbey Station road. At the junction turn right into Shires Lane stiles until the buildings of Calm Slate Farm can be passing the Sports Grounds on your right. At the seen. Aim for the farm buildings and pass through next junction turn left on to Low Lane, and after a a metal gate with a yellow band on the top. Turn With return on the Embsay few yards take the Footpath on the right to Eastby. right and go round the farm buildings passing an and Bolton Abbey office for Yorkshire Ice Cream on your right. (There Steam Railway Follow the wall on your right to the end then turn is an ice cream parlour/restaurant and children’s left on to a farm track. Go through the farm gate play area where refreshments can be purchased). going straight ahead, and then right between the Continue along the track in front of the farmhouse buildings. Before the second silo climb the steps on until you reach a track just after the cattle grid. your left, and carefully make your way across the tyres surrounding the silage clamp to a stile. Cross Bear right to the junction where you turn left on to he walk takes you to Bolton Abbey Station this stile going straight ahead to a second stile a gated road. You stay on this road until you reach where you can then take the train back to where the path takes you alongside the allotments. -

Black's Guide to Devonshire

$PI|c>y » ^ EXETt R : STOI Lundrvl.^ I y. fCamelford x Ho Town 24j Tfe<n i/ lisbeard-- 9 5 =553 v 'Suuiland,ntjuUffl " < t,,, w;, #j A~ 15 g -- - •$3*^:y&« . Pui l,i<fkl-W>«? uoi- "'"/;< errtland I . V. ',,, {BabburomheBay 109 f ^Torquaylll • 4 TorBa,, x L > \ * Vj I N DEX MAP TO ACCOMPANY BLACKS GriDE T'i c Q V\ kk&et, ii £FC Sote . 77f/? numbers after the names refer to the page in GuidcBook where die- description is to be found.. Hack Edinburgh. BEQUEST OF REV. CANON SCADDING. D. D. TORONTO. 1901. BLACK'S GUIDE TO DEVONSHIRE. Digitized by the Internet Archive in 2010 with funding from University of Toronto http://www.archive.org/details/blacksguidetodevOOedin *&,* BLACK'S GUIDE TO DEVONSHIRE TENTH EDITION miti) fffaps an* Hlustrations ^ . P, EDINBURGH ADAM AND CHARLES BLACK 1879 CLUE INDEX TO THE CHIEF PLACES IN DEVONSHIRE. For General Index see Page 285. Axniinster, 160. Hfracombe, 152. Babbicombe, 109. Kent Hole, 113. Barnstaple, 209. Kingswear, 119. Berry Pomeroy, 269. Lydford, 226. Bideford, 147. Lynmouth, 155. Bridge-water, 277. Lynton, 156. Brixham, 115. Moreton Hampstead, 250. Buckfastleigh, 263. Xewton Abbot, 270. Bude Haven, 223. Okehampton, 203. Budleigh-Salterton, 170. Paignton, 114. Chudleigh, 268. Plymouth, 121. Cock's Tor, 248. Plympton, 143. Dartmoor, 242. Saltash, 142. Dartmouth, 117. Sidmouth, 99. Dart River, 116. Tamar, River, 273. ' Dawlish, 106. Taunton, 277. Devonport, 133. Tavistock, 230. Eddystone Lighthouse, 138. Tavy, 238. Exe, The, 190. Teignmouth, 107. Exeter, 173. Tiverton, 195. Exmoor Forest, 159. Torquay, 111. Exmouth, 101. Totnes, 260. Harewood House, 233. Ugbrooke, 10P. -

TAUWI Response to Ofcom Consultation

TELECOMMUNICATION ASSOCIATION OF THE UK WATER INDUSTRY - TAUWI - RESPONSE TO OFCOM’S CONSULTATION On Spectrum Management Strategy Ofcom’s approach to and priorities for spectrum management over the next ten years INTRODUCTION This response is provided by the Telecommunications Association of the UK Water Industry (TAUWI) on behalf of its members: Anglian Water Services Ltd Severn Trent Water Ltd Black Sluice Internal Drainage Board South East Water Ltd Sembcorp Bournemouth Water South Staffordshire Water Bristol Water plc South West Water Services Ltd Cambridge Water plc Southern Water plc Dee Valley Water plc States of Jersey Transport and Technical Natural Resources Wales Services Department Environment Agency Sutton & East Surrey Water plc Essex & Suffolk Water Thames Water Utilities Ltd Hartlepool Water United Utilities Water plc Lindsey Marsh Drainage Board Veolia Water Central Welsh Water Veolia Water East Ltd Northern Ireland Water Ltd Veolia Water South East Ltd Northumbrian Water Ltd Wessex Water Services Ltd Scottish Water Yorkshire Water Services Ltd Atkins Ltd act as the main point of contact for TAUWI members and represent their interests on a range of matters, including responding to strategic consultation documents on their behalf. This response has been circulated for review to each of the 29 member organisations that form TAUWI and therefore negates the need for submissions from individual water companies. The Association was formed in April 2004 and replaces the Telecommunications Advisory Committee (TAC) which for the previous 14 years had acted as the focus for the UK Water Industry in relation to fixed and mobile communications and scanning telemetry from a technical and regulatory aspect. -

'Knight Frank Local View West Country, 2014'

local View THE WEST COUNTRY • 2014 WELCOME TO LOCAL VIEW WHERE DO OUR BUYERS COME FROM? MEET THE TEAM William Morrison Welcome to the latest edition of Local View, our seasonal update on the property markets that matter T +44 1392 848823 to you. Along with a brief review of activity in the West Country, we have also included a preview of [email protected] Specialism: Prime country houses just some of the beautiful properties we currently have available. Please contact your local team for and farms and estates more information and to find out what other opportunities we can offer. Years at Knight Frank: 15 Richard Speedy As we enter 2014 we are already seeing signs that the market T +44 1392 848842 will continue apace this year and certainly we think it is the year “In 2014 we predict that the market will take off very early in [email protected] for buyers and sellers to get on with things. Without wishing January with a good full 12 months ahead of us for selling.” Specialism: Waterfront and country the year away, 2015 will be a General Election year and the 26% 47% 27% property throughout South Devon Will Morrison market notoriously goes quiet before that event. Our best London and Local Area Rest of the UK International and Cornwall Office Head advice is to take full advantage of the better market 2014 will Years at Knight Frank: 10 be. Whilst we are likely to see an increase of property coming Christopher Bailey to the market in the next 6-12 months, there will be SALES BY PRICE BAND T +44 1392 848822 a significant increase in activity from buyers as well. -

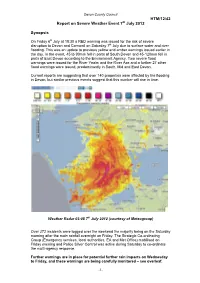

Cc100712cba Severe Weather Event 7Th July 2012

Devon County Council HTM/12/42 Report on Severe Weather Event 7 th July 2012 Synopsis On Friday 6 th July at 18:30 a RED warning was issued for the risk of severe disruption to Devon and Cornwall on Saturday 7 th July due to surface water and river flooding. This was an update to previous yellow and amber warnings issued earlier in the day. In the event, 45 to 90mm fell in parts of South Devon and 45-120mm fell in parts of East Devon according to the Environment Agency. Two severe flood warnings were issued for the River Yealm and the River Axe and a further 27 other flood warnings were issued, predominantly in South, Mid and East Devon. Current reports are suggesting that over 140 properties were affected by the flooding in Devon, but similar previous events suggest that this number will rise in time. Weather Radar 03:05 7 th July 2012 (courtesy of Meteogroup) Over 272 incidents were logged over the weekend the majority being on the Saturday morning after the main rainfall overnight on Friday. The Strategic Co-ordinating Group (Emergency services, local authorities, EA and Met Office) mobilised on Friday evening and Police Silver Control was active during Saturday to co-ordinate the multi-agency response. Further warnings are in place for potential further rain impacts on Wednesday to Friday, and these warnings are being carefully monitored – see overleaf. -1- Devon County Council DCC’s Flood Risk Management, Highways and Emergency Planning Teams are working closely with the District Councils and the Environment Agency to coordinate a full response. -

A Summary of Climate Change Risks for the East of England

A Summary of Climate Change Risks for the East of England To coincide with the publication of the UK Climate Change Risk Assessment (CCRA) 2012 !"#$%&'()*+(,%-&(,./"%.0 ! Front cover - Essex and Suffolk Water have begun construction of the ‘Abberton Reservoir Enhancement’ to enlarge the capacity of the company’s existing reservoir. This resource is required to provide Essex with the amount of water needed to ensure a continued future supply to customers over the next 25 years. 1 - Office for National Statistics, 2009. National statistics regional trends. 2 - Office for National Statistics, 2009. National statistics regional trends. 3 - East of England Catchment Abstraction Management Strategies (CAMS) – Environment Agency 4 - East of England Regional Assembly Regional Flood Risk Appraisal March 2009. 5 - UK CCRA 2012 "# !"#$%&'()*+(,%-&(,./"%.0 Introduction The East of England is the second largest English Region These transfers are crucial to the maintenance of public and covers 15% of the total area of England. water supplies and also provide support for agriculture It contains the counties of Bedfordshire, Cambridgeshire, and the water environment, especially during drought Essex, Hertfordshire, Norfolk and Suffolk and the unitary periods. authorities of Central Bedfordshire, Bedford Borough, Water resource management is particularly important Luton, Peterborough, Southend-on-Sea and Thurrock. considering the high levels of planned growth and a The major cities and towns in the region include Norwich, particularly extensive area of important wetland and Cambridge, Peterborough, Stevenage, Ipswich, Colchester, other water dependant habitats. Water resources are also Southend-on-Sea and Luton. These urban centres are under pressure from industries such as agriculture, with complemented by extensive rural areas. -

South Devon Estuaries Environmental Management Plan 2018 – 2024

South Devon Estuaries Environmental Management Plan 2018 – 2024 Area of Outstanding Natural Beauty www.southdevonaonb.org.uk 1 South Devon Estuaries Key facts The AONB contains the five estuaries of the Yealm, Erme, Avon, Salcombe-Kingsbridge and Dart. The far west is bordered by Plymouth Sound. They are a defining feature of the South Devon AONB. All are ria-type estuaries, drowned river valleys, formed by the eroding action of rivers carving through the surface geology and flooding to their present geography towards the end of the last Ice Age. The Salcombe-Kingsbridge estuary is a classic dendritic-ria with its many finger-like ria-formed creeks. All of our estuaries are unique in their own ways and range from the highly freshwater dominated Dart estuary to the highly seawater dominated Salcombe- Kingsbridge estuary – some describing it as a tidal marine inlet. Being ria-formed, they tend to be deep watered and have become important and popular ports and water-based recreation designations; they range from the small privately owned Erme estuary that does fully drain at low tide to the more cosmopolitan Dart estuary that attracts some of the world’s largest cruise liners. All of our estuaries still retain large areas of relatively unspoilt and undeveloped bed, foreshore and shoreline but with their considerable history of human use and harvesting, none can be described as being completely natural or unspoilt. However, they supply considerable ‘ecosystem services’ to the local natural beauty and communities and several are formally designated and protected in recognition of their rich and diverse natural history.