1 Last Sunday, I Preached on the Sacrament of Confession, Also

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Church and Liturgical Objects and Terms

Church and Liturgical Objects and Terms Liturgical Objects Used in Church The chalice: The The paten: The vessel which golden “plate” that holds the wine holds the bread that that becomes the becomes the Sacred Precious Blood of Body of Christ. Christ. The ciborium: A The pyx: golden vessel A small, closing with a lid that is golden vessel that is used for the used to bring the distribution and Blessed Sacrament to reservation of those who cannot Hosts. come to the church. The purificator is The cruets hold the a small wine and the water rectangular cloth that are used at used for wiping Mass. the chalice. The lavabo towel, The lavabo and which the priest pitcher: used for dries his hands after washing the washing them during priest's hands. the Mass. The corporal is a square cloth placed The altar cloth: A on the altar beneath rectangular white the chalice and cloth that covers paten. It is folded so the altar for the as to catch any celebration of particles of the Host Mass. that may accidentally fall The altar A new Paschal candles: Mass candle is prepared must be and blessed every celebrated with year at the Easter natural candles Vigil. This light stands (more than 51% near the altar during bees wax), which the Easter Season signify the and near the presence of baptismal font Christ, our light. during the rest of the year. It may also stand near the casket during the funeral rites. The sanctuary lamp: Bells, rung during A candle, often red, the calling down that burns near the of the Holy Spirit tabernacle when the to consecrate the Blessed Sacrament is bread and wine present there. -

Vestments and Sacred Vessels Used at Mass

Vestments and Sacred Vessels used at Mass Amice (optional) This is a rectangular piece of cloth with two long ribbons attached to the top corners. The priest puts it over his shoulders, tucking it in around the neck to hide his cassock and collar. It is worn whenever the alb does not completely cover the ordinary clothing at the neck (GI 297). It is then tied around the waist. It symbolises a helmet of salvation and a sign of resistance against temptation. 11 Alb This long, white, vestment reaching to the ankles and is worn when celebrating Mass. Its name comes from the Latin ‘albus’ meaning ‘white.’ This garment symbolises purity of heart. Worn by priest, deacon and in many places by the altar servers. Cincture (optional) This is a long cord used for fastening some albs at the waist. It is worn over the alb by those who wear an alb. It is a symbol of chastity. It is usually white in colour. Stole A stole is a long cloth, often ornately decorated, of the same colour and style as the chasuble. A stole traditionally stands for the power of the priesthood and symbolises obedience. The priest wears it around the neck, letting it hang down the front. A deacon wears it over his right shoulder and fastened at his left side like a sash. Chasuble The chasuble is the sleeveless outer vestment, slipped over the head, hanging down from the shoulders and covering the stole and alb. It is the proper Mass vestment of the priest and its colour varies according to the feast. -

What They Wear the Observer | FEBRUARY 2020 | 1 in the Habit

SPECIAL SECTION FEBRUARY 2020 Inside Poor Clare Colettines ....... 2 Benedictines of Marmion Abbey What .............................. 4 Everyday Wear for Priests ......... 6 Priests’ Vestments ...... 8 Deacons’ Attire .......................... 10 Monsignors’ They Attire .............. 12 Bishops’ Attire ........................... 14 — Text and photos by Amanda Hudson, news editor; design by Sharon Boehlefeld, features editor Wear Learn the names of the everyday and liturgical attire worn by bishops, monsignors, priests, deacons and religious in the Rockford Diocese. And learn what each piece of clothing means in the lives of those who have given themselves to the service of God. What They Wear The Observer | FEBRUARY 2020 | 1 In the Habit Mother Habits Span Centuries Dominica Stein, PCC he wearing n The hood — of habits in humility; religious com- n The belt — purity; munities goes and Tback to the early 300s. n The scapular — The Armenian manual labor. monks founded by For women, a veil Eustatius in 318 was part of the habit, were the first to originating from the have their entire rite of consecrated community virgins as a bride of dress alike. Belt placement Christ. Using a veil was Having “the members an adaptation of the societal practice (dress) the same,” says where married women covered their Mother Dominica Stein, hair when in public. Poor Clare Colettines, “was a Putting on the habit was an symbol of unity. The wearing of outward sign of profession in a the habit was a symbol of leaving religious order. Early on, those the secular life to give oneself to joining an order were clothed in the God.” order’s habit almost immediately. -

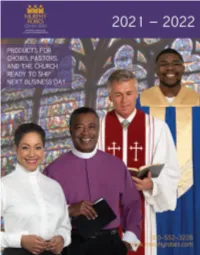

Murphycatalog.Pdf

® Welcome to our Qwick-Ship catalog of Visit www.MurphyRobes.com for our entire GUARANTEED SATISFACTION ready-to-ship items for choirs, pastors, and the collection containing hundreds of items Every item in this catalog is backed by our church - an unbelievable selection of quality available custom made. Qwick-Ship® Guarantee of Satisfaction. If you products in an incredible range of sizes you are not completely satisfied, return it, unused won't find anywhere else. and unworn, within 30 days of receipt for exchange or refund. READY TO SHIP Items in this catalog are available exactly as shown and described in sizes on referenced size chart, ready to ship next business day following receipt of order. Shipping costs vary based on speed. WHITE GLOVE® PACKAGING SERVICE With our exclusive White Glove® Packaging Service, all apparel is placed on a deluxe hanger, individually bagged and packed in a specially designed shipping container to minimize wrinkling at no extra charge. STANDARD SIZING Qwick-Ship® sizing patterns have been carefully developed to fit "average" body types with non-exceptional proportions. Order by size using item specific size charts. EXTRA SAVINGS Qwick-Ship® items are specially priced to offer extra savings over identical custom made items. Savings are shown throughout this catalog on items available custom made. AVAILABLE CUSTOM MADE To order an item in sizes, fabrics, colors or with other details than shown, ask us for assistance with custom made ordering. Allow a minimum of 8 weeks for manufacture and shipment of custom made items. We make every attempt to show fabric colors as accurately as possible. -

Stole, Maniple, Amice, Pallium, Ecclesiastical Girdle, Humeral Veil

CHAPTER 8 Minor Vestments: Stole, Maniple, Amice, Pallium, Ecclesiastical Girdle, Humeral Veil Introduction vestment of a pope, and of such bishops as were granted it by the pope as a sign of their metropolitan status.4 The term ‘minor vestments’ is used here to signify a Mostly, but not exclusively, the pallium was granted by number of smaller items which are not primary dress, the pope to archbishops – but they had to request it for- in the sense that albs, chasubles, copes and dalmatics mally, the request accompanied by a profession of faith are dress, but are nevertheless insignia of diaconal and (now an oath of allegiance). It seems to have been con- priestly (sometimes specifically episcopal) office, given sidered from early times as a liturgical vestment which at the appropriate service of ordination or investiture. could be used only in church and during mass, and, in- Other insignia are considered in other sections: the mitre creasingly, only on certain festivals. In the sixth century (Chapter 1); ecclesiastical shoes, buskins and stockings it took the form of a wide white band with a red or black (Chapters 7 and 9), and liturgical gloves (Chapter 10). cross at its end, draped around the neck and shoulders The girdle, pallium, stole and maniple all have the in such a way that it formed a V in the front, with the form of long narrow bands. The girdle was recognised ends hanging over the left shoulder, one at the front and as part of ecclesiastical dress from the ninth century at one at the back. -

1 the Methodist Church of Southern Africa Doctrine

Disclaimer: Please note that this paper does not represent the views of the Methodist Church of Southern Africa or DEWCOM, unless specified otherwise. Status of paper: Adopted by DEWCOM URL: http://mcsadewcom.blogspot.com THE METHODIST CHURCH OF SOUTHERN AFRICA DOCTRINE, ETHICS AND WORSHIP COMMITTEE GUIDELINES FOR THE USE OF CLERICAL VESTMENTS AND FORMAL METHODIST ECCLESIASTICAL ATTIRE. What are Clerical Vestments and why do Ministers and Preachers wear them? • The distinctive clothes normally worn by Ministers and Preachers in the course of conducting Services of Worship. • It is not the purpose of distinctive clerical and liturgical clothing to give the impression of superior status to the Minister or Preacher. Ministers and Preachers, when conducting Services of Worship, presiding over the Sacraments and preaching, do not do so as individuals. While individuality, talent and skill enhance the Minister or Preacher’s proclamation of God’s grace, the individuality of the Minister or Preacher is of secondary importance to the Church’s proclamation of the gospel of grace. • Ministers and Preachers represent the Church of Christ in all places and all ages, drawing the authority of their message from the gracious call of God upon their lives, their dependence upon the leading of the Holy Spirit, their subjection to the tradition of the Apostles and the Holy Scriptures. • It is the purpose of Clerical vestments to mask the individuality of the Minister or Preacher and demonstrate that the Minister or Preacher is a servant of Jesus Christ and the whole Church in all places and all ages. • The Methodist tradition follows the practice of John Wesley who, although he was an Anglican priest, chose the “plainness” of the Puritan pattern of clerical vestment. -

The Magazine of the Episcopal Diocese of Ohio Fall 2019 • Volume 123 • Number 3 the Episcopal Church

THE MAGAZINE OF THE EPISCOPAL DIOCESE OF OHIO FALL 2019 • VOLUME 123 • NUMBER 3 THE EPISCOPAL CHURCH IN THE ANGLICAN COMMUNION A global community of over 80 million members in 44 regional and national member churches. The Most Rev. Justin Welby Archbishop of Canterbury IN THE UNITED STATES A community of more than 2 million members in 110 dioceses in the Americas and abroad. Established 1789. The Most Rev. Michael Bruce Curry Presiding Bishop IN THE DIOCESE OF OHIO A community of 16,000 baptized members in 86 parishes in the northern 48 counties of the State of Ohio. Established 1817. "Physically, we BISHOP OF OHIO The Rt. Rev. Mark Hollingsworth, Jr. are one; the CHURCH LIFE MAGAZINE E-mail: [email protected] The Rt. Rev. Mark Hollingsworth, Jr., Publisher question is Jessica Rocha, Editor & Designer Beth Bergstrom, Assistant Editor whether or not ©Church Life! Magazine (ISSN 8750-8613) Published four times per year in March, June, September, and December we will choose by The Episcopal Diocese of Ohio 2230 Euclid Avenue to live as one." Cleveland, OH 44115-2499 Postmaster: Send change of address to Church Life Magazine -page 5 2230 Euclid Avenue Cleveland, OH 44115 Periodicals postage paid at Cleveland, OH and at additional mailing offices. Member of the Episcopal Communicators. IMPORTANT All households of the Diocese of Ohio should receive Church Life Magazine. If you are not currently receiving it, or if you need to change your delivery address, please contact the Communications Office with your name, address, and parish. Phone: -

Concordia Theological Monthly

CONCORDIA THEOLOGICAL MONTHLY The Eclipse of Lutheranism in 17th-Century Czechoslovakia MARIANKA SASHA FOUSEK [he Martyrs of Christ - A Sketch of the Thought of Martin Luther on Martyrdom DOUGLAS C. STANGE Lutheran and Protest Vestment Practices in the United States and Canada: A Survey ARTHUR CARL PIEPKORN Homiletics Theological Observer Book Review Vol. xxxvn November 1966 No. 10 Lutheran and Protestant Vestment Practices In the United States and Canada: A Survey! ARTHUR CARL PIEPKORN A. THE LUTHERAN TRADITION2 itself to what we know as the surplice, he alb, sleeved and often sleeveless, never passed wholly out of use in the Tboth with cincture and in the modified Lutheran Church. Neither did the chasuble. uncinctured form that gradually assimilated The cope has survived primarily, but not exclusively, as an episcopal vestment in 1 This study summarizes the detailed docu Scandinavia. The amice persisted in a sense mentation assembled in connection with the as the collar of the Swedish alb. The black production of an article on "Vestments, Ecclesi astical: Lutheran and Protestant" for the Encyclo gown, either with bands or with the "mill paedia Britannica. It covers the major traditions stone" type of collar (which still survives and church bodies of the Western tradition in parts of European Lutheranism), became (except the Roman Catholic and Protestant general as liturgical vesture only in the Episcopal Churches) in the United States and Canada. For the most part, it reflects the state 19th century. In parts of Scandinavia the ments made by persons whom the head of the black scarf worn with the gown became church body in question had designated to pro a stylized appendage ( "black stole"). -

NOVEMBER 2016 WORD.Indd

Volume 60 No. 9 November 2016 VOLUME 60 NO. 9 NOVEMBER 2016 COVER: ICON DEESIS EDITORIAL at St. Siouan Monastery Chapel in Wichita, Kansas. contents Icon written by the hand of Janet Jaime, [email protected] 3 EDITORIAL by Bishop JOHN Am I Any More Ready to Receive Christ 4 AND THE WORD BECAME FLESH by Fr. Stavros N. Akrotirianakis Today Than Israel Was 2,000 Years Ago? 6 METROPOLITAN JOSEPH VISITS METROPOLITAN TIKHON AT THE OCA CHANCERY ast week a young man came to me lamenting change our lives to re ect our beliefs and values. is 8 PREPARING FOR MASS over not living as if Christ is resurrected and the takes some deliberate e ort. by V. Rev. John W. Fenton tomb is empty. I invited him to explore with e Church has given us two major fasting periods 15 IOCC me what that “living after the Resurrection” each year to bring us back to the reality of God’s presence. L should look like. He thought that there should We celebrate His Nativity and Resurrection, preceded by 16 ORATORICAL FESTIVAL by Jordan Khabbaz be some peace, arising from a simple understanding that periods of fasting, intensi ed worship, almsgiving and God has accomplished already those things that we fear private prayer. e messages focus on what God does 18 EXPERTS “RE-THINK” SACRED ARTS AT ST. VLADIMIR’S SEMINARY and dread. We should not need to compete for God’s in our lives, and we are called to encounter Him. We attention or love; He has come to us! erefore we can look forward to the messages the Church provides 19 HELPING WOMEN SAVES LIVES should live without fear. -

A Handbook for Chalice Bearers Church of the Holy Spirit Anglican

A Handbook for Chalice Bearers Church of the Holy Spirit Anglican “Therefore, I urge you, brothers, in view of God’s mercy, to offer your bodies as living sacrifices, holy and pleasing to God—this is your spiritual act of worship.” (Romans 12:1 NIV) Purpose The chalice bearer plays a vital role in helping their ministers cultivate an environment in which worship may be celebrated with reverence and awe, allowing for full participation by the gathered assembly. Responsibilies A few reminders for Chalice Bearers: If you are unable to serve on your assigned day, please find your replacement. Please call Brenda Price and let her know of the replacement or trade of service dates. Please do not call the church office. Brenda will notify those involved. If you are ill or facing a travel emergency and are unable to find a replacement, please call Brenda as well, but remember that, under normal circumstances, making an effort to find replacements is your responsibility. Preparation The chalice bearer is to regard their office and assignments seriously, a commitment of time and talent in service to the Lord; a holy responsibility. It is important to learn the order of the service and liturgical terminology, understanding that in the Eucharist, God becomes present to us in the elements by the power of the Holy Spirit, making one a part of the working of this sacred time. Dress Serving in this highly visible role, please dress appropriately, by this we mean professional (basically business casual in our parish) with dark colored dress shoes (dark suede comfort shoes are fine – never appear in tennis shoes, flip-flops, jeans, shorts, etc.). -

Sacristan Training Manual

1 NEIGHBORS NORTH CATHOLIC COMMUNITY SACRISTAN MANUAL (Last revised October 2019, David Dashiell) “When the wine ran short, the mother of Jesus said to him, ‘They have no wine.’ Jesus said to her, ‘Woman, how does your concern affect me? My hour has not yet come.’ His mother said to the servers, ‘Do whatever he tells you.’” John 2:3-5 Just as Mary made sure nothing was lacking from the Feast and handed over its outcome to Jesus, we as sacristans seek to serve by preparing for the Mass, which foreshadows the Wedding Feast of the Lamb. We prepare the sacred vessels, and take care of the sacristy, providing for the needs of the lay ministers and clergy. As sacristans, we follow in the footsteps of the great sacristan saints such as Thérèse of Liseux and John Vianney. We take the example of Our Lord as our model of service and humility (see John 13:12-17). Submitting our prayer and ministry to Jesus, we seek to serve our community as they come together to worship and receive our Eucharistic Lord. We are content to do much of our ministry behind the scenes, knowing that the Lord sees what no one else does. 2 Things to Keep in Mind A Quick Review • As ministers, we are leaders performing our work in view of the entire congregation. As leaders, we ought to model the Church’s teaching. The Church has guidelines for when to sit, stand, kneel, genuflect, and bow during Mass: • Bow from the waist whenever you pass by the altar. -

New Jersey Catholic Records Newsletter, Vol. 4, No.1, 2021

Seton Hall University eRepository @ Seton Hall New Jersey Catholic Historical Commission newsletters Archives and Special Collections 2021 New Jersey Catholic Records Newsletter, Vol. 4, No.1, 2021 New Jersey Catholic Historical Commission Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarship.shu.edu/njchc Newsletter of the New Jersey Catholic Historical Commission April 2021 Volume IV, Issue 1 Remembering Monsignor Francis R. Seymour, KHS (1937– 2018) It is with great sadness that we announce the death of Monsignor Francis R. Seymour, KHS, who served for many years as the first Ar- chivist for the Archdiocese of Newark when he was named to this position in 1969. He was also a founding member of the New Jersey Catholic Historical Commission in 1976 and became Chair of this organization in 2009. The contributions Monsignor Seymour made to the Monsignor William Noé Field Archives & Special Collections Center were many and memorable. Counted among his most important and lasting works are his careful organization of research files related to the priest community and his collecting of important docu- mentation, from autographed photographs to memorial cards to parish histories and many other items and objects related to the story of Catholic New Jersey. It was in the personal sharing of his knowledge and recollections where he really brought history to life. His memory for details was remarkable and brought both enthusiasm and a gentle touch to his interactions with the many people he touched during the course of his life. On a personal level, Monsignor Seymour will be remembered fondly and missed greatly by the many individuals who had the privilege to learn from his example and had the privilege to call him a colleague and friend.