A Brand Loyalty Model for Arts Festivals

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

How Ninja from Die Antwoord Performs South African White Masculinities Through the Digital Archive

ZEF AS PERFORMANCE ART ON THE ‘INTERWEB’: How Ninja from Die Antwoord performs South African white masculinities through the digital archive by Esther Alet Rossouw Submitted in fulfilment of the requirements of the degree MAGISTER ARTIUM in the Department of Drama Faculty of Humanities University of Pretoria Supervisor: Dr M Taub AUGUST 2015 1 ABSTRACT The experience of South African rap-rave group Die Antwoord’s digital archive of online videos is one that, in this study, is interpreted as performance art. This interpretation provides a reading of the character Ninja as a performance of South African white masculinities, which places Die Antwoord’s work within identity discourse. The resurgence of the discussion and practice of performance art in the past thirty years has led some observers to suggest that Die Antwoord’s questionable work may be performance art. This study investigates a reconfiguration of the notion of performance art in online video. This is done through an interrogation of notions of risk, a conceptual dimension of ideas, audience participation and digital liveness. The character Ninja performs notions of South African white masculinities in their music videos, interviews and short film Umshini Wam which raises questions of representation. Based on the critical reading of Die Antwoord’s online video performance art, this dissertation explores notions of Zef, freakery, the abject, new ethnicities, and racechanges, as related to the research field of whiteness, to interpret Ninja’s performance of whiteness. A gendered reading of Die Antwoord’s digital archive is used to determine how hegemonic masculinities are performed by Ninja. It is determined that through their parodic performance art, Die Antwoord creates a transformative intervention through which stagnant notions of South African white masculinity may be reconfigured. -

"The Official Kiaat Magazine" Kiaat Diaries from the Editor

KiaatVolume 3, Issue 1 March 2014 Diaries"The Official Kiaat Magazine" Kiaat Diaries From The Editor... Taking over the reins from you bow down – you do not one of the best designers I embrace what I offer, but you have come across was – to accept the bowl of old tuna put it simply – an almost and cow dung I feed you. I impossible task. However, the get straight to the point, no team and resources I have at sugar coating or B.S – so my disposal have been key if there’s something worth in this project being able to reporting, better be sure I come together. will have the midget in a When in Rome, do as…….? wheelchair with a blind 80- Not in the living hell!! When year old trans-gendered Jew in Rome, eat Roman noodles. on his lap. Editor: Geuren Pierce Hendricks So when in my presence, Enjoy the show!! Cover Art: "Pineapple" on Groenkloof In This Edition: campus courtesy of Innocent Mulalo Production Coordinator: RAMming it up! 3 Geuren Pierce Hendricks & Janco Hurter Cleaning the prison floor 5 Magazine Design: BTrue2U 7 Geuren Pierce Hendricks & Janco Hurter Orientation Week 2014 10 Proof Reading: A Smile 11 Mark Hubbard Socials 13 Publications Committee: Stress Management 14 Geuren Pierce Hendricks Mark Hubbard Lords of London 14 Janco Hurter Cayden Nel Express Your Faith 15 Marvin Frans Khumbulani Mdhluli Res Sport Leagues 16 Rodney Xaba Blessing Mseleku Kiaat Diaries Column 16 Thabang Mabena Kobus Labuschagne 2 Kiaat Diaries RAMming it up! Foals have since swept the world shaking the globe with their bass By Cayden Nel by playing all around the globe. -

Entertainment and Media Outlook: 2013 – 2017

4th annual edition: PwC’s annual forecast of advertising and consumer spending across 3 countries and 12 industry segments South African entertainment and media outlook: 2013 – 2017 In-depth analysis of the trends shaping the entertainment industry in South Africa, Nigeria and Kenya www.pwc.co.za/outlook ii | South African entertainment and media outlook: 2013-2017 (including Nigeria and Kenya) 4th annual edition PwC South African entertainment & media outlook: 2013-2017 PwC fi rms help organisations and individuals create the value they are looking for. We are a network of fi rms in 158 countries with more than 180 000 people who are committed to delivering quality in assurance, tax and advisory services. PricewaterhouseCoopers Inc. 2 Eglin Road Sunninghill, 2157 +27 11 797 4000 www.pwc.co.za © 2013 Published in South Africa by PricewaterhouseCoopers. All rights reserved. “PwC” is the brand under which member fi rms of PricewaterhouseCoopers International Limited (PwCIL) operate and provide services. Together, these fi rms form the PwC network. Each fi rm in the network is a separate legal entity and does not act as agent of PwCIL or any other member fi rm. PwCIL does not provide any services to clients. PwCIL is not responsible or liable for the acts or omissions of any of its member fi rms nor can it control the exercise of their professional judgment or bind them in any way. Editorial team Vicki Myburgh Nana Madikane Osere Alakhume Michael Mugasa South African South African Nigerian Kenyan Entertainment & Entertainment and Entertainment and -

Ramfest – Final Line-Up Announced

RAMfest – Final Line-up Announced: 5 cities! 5 days! 7 stages! Local and international artists! The line-up is final at last. In 2012 we bring you not two, not three, but four international acts! RAMfest has upped the game and we are proud to announce that AWOLNATION (USA) will be joining the international line-up together with In Flames (Sweden), Infected Mushroom (Israel) and drum and bass master NETSKY ft. MC Darrison (Belgium and UK). SA fans were thrilled when RAMfest announced the first headliner In Flames in November last year. In Flames vocalist Anders Friden says that the band is excited about their upcoming performances at RAMfest (JHB and CT): “We are really looking forward to touring South Africa. There are many countries that we have visited many times over, but this will be a completely new experience for us. Get ready to hear some delicious metal brewed and matured in Sweden; we hope to see many of you!" Infected Mushroom and NETSKY ft. MC Darrison were announced earlier this year and with AWOLNATION also joining the line up, South Africa is in for a phenomenal treat. With the help of our sponsors we have managed to put together the ultimate alternative playground. Book your tickets now and join us at one of the selected venues for SA's best loved annual music festival: Dates: Friday 02 March 2012: Port Elizabeth, Hume Park Saturday 03 March 2012: Bloemfontein, Mystic Boer Friday 09 March 2012: Durban, Origin Night Club Saturday 10 March 2012: Johannesburg, Riversands Farm Sunday 11 March 2012: Cape Town Ostrich Ranch, N7 *Please note that the international acts will only be performing at RAMfest in Joburg and Cape Town and Netsky will also be in Durban. -

Entertainment and Media Outlook: 2015 – 2019 South Africa – Nigeria – Kenya

Entertainment and media outlook: 2015 – 2019 South Africa – Nigeria – Kenya 6th annual edition September 2015 An in-depth analysis of the trends shaping the entertainment and media industry in South Africa, Nigeria and Kenya www.pwc.co.za/outlook Use of Outlook data The data in PwC’s Entertainment and media outlook: 2015-2019 (South Africa, Nigeria & Kenya) (“the Outlook”) is a comprehensive source of consumer and advertising data, which is also available online on www.pwc.co.za/outlook. PwC continually seeks to update the online Outlook data, so please note that the data in this publication may not be aligned with the data found online. The Outlook is the most up-to-date source of consumer and advertising spend data. This document is provided by PwC for general guidance only and does not constitute the provision of legal advice, accounting services, investment advice or professional consulting of any kind. The information provided herein should not be used as a substitute for consultation with professional tax, accounting, legal or other competent advisors. Before making any decision or taking any action, you should consult with a professional advisor who has been provided with all the pertinent facts relevant to your particular situation. The information in this document is provided ‘as is’, with no assurance or guarantee of completeness, accuracy or timeliness of the information and without warranty of any kind, express or implied, including but not limited to warranties of performance, merchantability and fitness for a particular purpose. Outlook content must not be excerpted, used, or presented in any portion that would render it misleading in any manner or that fails to provide sufficient context. -

Removing the Black Tape : Survivor Speaks out SA’S Dagga Couple

A A C T I V A T E RHODES UNIVERSITY INDEPENDENT STUDENT NEWSPAPER EDITION 2 • 20 MARCH 2012 • SINCE 1947 Jabu Stone in G’town Removing the black tape : Survivor speaks out SA’s Dagga Couple GIVEAWAY TONIGHT: 2 Double tickets to SPLASHY FEN! Photo Feature: KNOW YOUR MEAT* *Warning: this feature is not for the faint-hearted Edition 2 . 20 March 2012 Page 7: Editor-in-chief: RU student forum Lauren Kate Rawlins Deputy Editor: Page 10: Isabelle Anne Abraham Content Editor: LARK interview Kayla Roux Managing Editor Palesa Mashigo Page 11: Online Editor: Alexander Venturas Chief Media Supervisor: Political correctness Megan Ellis and power of the Chief Sub-Editor: Matthew Kynaston tongue Chief Designer Simone Loxton Assistant Designer: Page 15: Mignon van Zyl Chief Pics Editor: HIGHLIGHTS Anton Scholtz Know your meat Assistant Pics Editor: Niamh Walsh-Vorster Page 18: Illustrator: Katja Schreiber Singing for sex? News Editor: Sibulele Mabusela Deputy News Editor: Page 20: Neo Koza Politics Editor: Sexual abuse and the Marc Davies Business Editor: male myth Njabulo Nkosi C&A Editor: Alexa Sedgwick Page 27: Features Editor: Karlien van der Wielen Features Assistant Editor: Jack Parow performs live on the main stage at the 2010 Splashy Fen music festival. Splashy is Win a meal at La Trattoria Nina McFall held annually over the Easter weekend in the foothills of the Drakensberg Mountains and is Lifestyle Editor: South Africa’s longest running music festival. This year’s festival promises to be the best yet, Sarisha Dhaya win one of two double tickets with Activate tonight! Turn to Page 8 for more details… A & E Editor: Elna Schütz Front Page Picture: Jabu Stone is regarded in many circles as ‘Mr Dreads’ because of his Sports Editor: dedication and vigorous pursuit of the African identity through the promotion of braids and Bridgette Hall African locks amongst African people. -

A Musical Ethnography of the Kaapse Klopse Carnival in Cape Town, South Africa

DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY A musical ethnography of the Kaapse Klopse carnival in Cape Town, South Africa Gregory, Jonathan Award date: 2018 Awarding institution: Queen's University Belfast Link to publication Terms of use All those accessing thesis content in Queen’s University Belfast Research Portal are subject to the following terms and conditions of use • Copyright is subject to the Copyright, Designs and Patent Act 1988, or as modified by any successor legislation • Copyright and moral rights for thesis content are retained by the author and/or other copyright owners • A copy of a thesis may be downloaded for personal non-commercial research/study without the need for permission or charge • Distribution or reproduction of thesis content in any format is not permitted without the permission of the copyright holder • When citing this work, full bibliographic details should be supplied, including the author, title, awarding institution and date of thesis Take down policy A thesis can be removed from the Research Portal if there has been a breach of copyright, or a similarly robust reason. If you believe this document breaches copyright, or there is sufficient cause to take down, please contact us, citing details. Email: [email protected] Supplementary materials Where possible, we endeavour to provide supplementary materials to theses. This may include video, audio and other types of files. We endeavour to capture all content and upload as part of the Pure record for each thesis. Note, it may not be possible in all instances to convert analogue formats to usable digital formats for some supplementary materials. -

Music Festivals

August 2011 • aboutime.co.za • Your copy to keep music festivals TIRED OF CRIME? TS N TE N CO contents On the Cover Once the domain of students and hippies, music festivals have long hit the mainstream, attracting everyone from fashionistas to families as they pop up in all corners of the globe. Here’s our pick of some of the best rock fests on offer. Cover pic © iStockphoto.com 28 Rock Around the Block – The World’s Best 56 On the Frontlines of a Rhino Poaching War Music Festivals OppiKoppi – Photo Essay Tiger Mother – Pat Evans Features 34 68 50 And All That Jazz! 107 The Home of Golf 44 Winter, Durban Style 66 Fine Fare at Fairlawns The Complete Winelands Escape – A Small, Sweet Taste of Pure Africa – Travel 55 72 The Grande Roche Hotel Lugenda Wilderness Camp 63 Hakuna Matata – Exploring Southern Zanzibar 96 Out of the Box 100 The Audi A6 – Light Years Ahead 98 Versatility and Comfort – The Amarok Single Cab Motoring 12 www.aboutime.co.za 28 Rock Around the Block – The World’s Best 56 On the Frontlines of a Rhino Poaching War Music Festivals 34 OppiKoppi – Photo Essay 68 Tiger Mother – Pat Evans 50 And All That Jazz! 107 The Home of Golf 44 Winter, Durban Style 66 Fine Fare at Fairlawns 55 The Complete Winelands Escape – 72 A Small, Sweet Taste of Pure Africa – The Grande Roche Hotel Lugenda Wilderness Camp 63 Hakuna Matata – Exploring Southern Zanzibar 96 Out of the Box 100 The Audi A6 – Light Years Ahead 98 Versatility and Comfort – The Amarok Single Cab TS N TE N CO contents 77 Cocktail Crazy! 83 Laat dié Feeste Musiek Werklik -

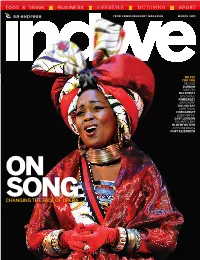

Mar 2011 on Song

FOOD & DRINK BUSINESS LIFESTYLE MOTORING SPORT SA EXPRESS YOUR COMPLIMENTARY MAGAZINE MARCH 2011 INDWE MAGAZINE WE FLY FOR YOU GEORGE DURBAN MAPUTO NELSPRUIT WINDHOEK KIMBERLEY GABORONE WALVIS BAY CAPE TOWN HOEDSPRUIT LUBUMBASHI EAST LONDON RICHARDS BAY BLOEMFONTEIN JOHANNESBURG PORT ELIZABETH ON SONG CHANGING THE FACE OF OPERA Y OUR COMPLIMENTARY MAGAZINE COMPLIMENTARY OUR IND15_001_OperaCover2_NEW.indd 1 16/02/2011 15:45 Kelderhof Country Village Kelderhof Country Village takes you back to a time when life was easier and less frenetic, when the simplest things brought the greatest pleasure. EXCELLENT LOCATION, EASY ACCESS Give your family the life they richly deserve at Kelderhof Country Village. Set amongst the sprawling vineyards of the picturesque Helderberg Winelands, this exclusive, secure lifestyle estate provides you with an outstanding opportunity to invest in your future. With easy access to the N2 and R102, Kelderhof Country Village is situated in close proximity to Stellenbosch, Somerset West and False Bay, and private schools, beaches, golf courses, health clinics and shopping malls are all a mere 5 to 10 minutes away. AUTHENTIC COUNTRY LIVING At Kelderhof Country Village you will discover the immense beauty and charm of the country lifestyle. Tree- lined avenues wind their way round the estate, converging on the central circle, featuring the Kelder Lifestyle Centre. Home to a diverse range of quality leisure facilities comprising a function room, swimming pool, tennis courts, exclusive gym, outdoor braai area and kids’ jungle gym, the Kelder Lifestyle Centre embodies the heart and soul of this lifestyle estate. Landscaped play parks, duck ponds and meandering waterways add to the allure and charm of this exquisite lifestyle estate.