Swimming As Play Gabor Csepregi

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Synchronized Swimming Record Book Was Years: Second Season Written and Edited by Regina Verlengiere

2014 STANFORD SYNCHRO 2014 STANFORD SCHEDULE Date Event/Opponent Location Time Jan. 24 Lindenwood University St. Charles, Mo. TBD Jan. 25 Lindenwood University St. Charles, Mo. TBD Feb. 8 Incarnate Word Stanford, Calif. 12 p.m. Feb. 9 Incarnate Word Stanford, Calif. 9 a.m. Feb. 15 Florida & Lindenwood Gainesville, Fla. TBD Feb. 16 Florida Gainesville, Fla. TBD Feb. 22 Arizona Stanford, Calif. 3 p.m. Feb. 23 Arizona Stanford, Calif. 10 a.m. March 1 Arizona State Mesa, Ariz. TBD March 2 Western Regionals Mesa, Ariz. All Day March 20-22 U.S. Collegiate Nationals Oxford, Ohio All Day 2014 QUICK FACTS General Information Athletic Communications and Media Relations Location: Stanford, CA 94305-6150 Synchro Contact: Regina Verlengiere Synchro Facility: Avery Aquatics Center Email: [email protected] Enrollment: 15, 870 (6,999 undergraduates) Office Phone: (650)723-0996 Founded: 1891 Media Relations Office: (650) 723-4418 Nickname: Cardinal Athletics Website: www.gostanford.com Colors: Cardinal and White Athletic Director: Bernard Muir Media Information President: John Hennessy Interview requests for players and coaches must be coordinated with Sport Administrator: Brian Talbot the Stanford Athletics Communications office. Visit www.gostanford. com for news releases, player profiles, and updated schedules and Coaching Staff results. Sara Lowe (Stanford, 2008) Head Coach: Credits: The 2014 Stanford synchronized swimming record book was Years: Second Season written and edited by Regina Verlengiere. Past design, layout and pro- Assistant Coach: Megan Azebu (Santa Clara, 2012) duction by Maggie Oren, MB Design. Photoraphy by John Todd, Don Athletic Trainer: Scott Anderson Feria and Richard Ersted. Sports Performance Coach: Rachel Hayes Synchro Office Phone: (650) 724-2395 WWW.GOSTANFORD.COM 2014 SYNCHRONIZED SWIMMING RECORD BOOK 2014 STANFORD ROSTER From left to right: Isabella Park, Leigh Haldeman, Evelyna Wang, Megan Hansley, Mina Shah, Marisa Tashima and Carolyn Morrice. -

Synchronized Skating Teams 2020

Synchronized Skating Teams For Skaters in Basic 4 and Up! 2020 – 2021 Training Season Info *Please note: Due to the Global Pandemic, the Chicago Red Line is currently planning on hosting a “Training Only Season”. Under this plan, the season will not include competitions or travel, and will focus on skater development. IMPORTANT: 2020 – 2021 Training Season Info Due to the Global Pandemic, the Chicago Red Line is currently planning on hosting a “Training Only Season”. Under this plan, the season will not include competitions or travel, and will focus on skater development. This training season will allow us to: • Work on individual skills and drills, that do not include physical touching • Keep socially distant during practice • Build up the skaters’ individual strengths, which will strengthen the team, when it is able to resume normally. • At a reduced dues cost, will allow families who have been impacted financially by the pandemic, to continue participating in their team sport. • Have the coaches loosely choreograph an ‘unconnected’ performance program, that if restrictions loosen, the skaters will be able to perform in a competition or ice show. • If restrictions / precautions lift enough to allow us to attend a competition, to collect fees at that time. Important Note about age: For our younger team, we are requiring at least an age of 7, as we believe that most 7 year olds will be able to understand the importance of Social Distancing on the ice, to maintain everyone’s safety. If you believe your child will struggle with maintaining physical distance from their teammates, we ask that you wait to join us until next season, when we hope to resume normal team practices. -

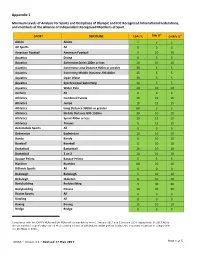

TDSSA Appendix 1

Appendix 1 Minimum Levels of Analysis for Sports and Disciplines of Olympic and IOC Recognized International Federations, and members of the Alliance of Independent Recognized Members of Sport 4 4 SPORT DISCIPLINE ESAs % GHs % GHRFs % Aikido Aikido 5 5 5 Air Sports All 0 0 0 American Football American Football 5 10 10 Aquatics Diving 0 5 5 Aquatics Swimming Sprint 100m or less 10 10 10 Aquatics Swimming Long Distance 800m or greater 30 5 5 Aquatics Swimming Middle Distance 200‐400m 15 5 5 Aquatics Open Water 30 5 5 Aquatics Synchronized Swimming 10 5 5 Aquatics Water Polo 10 10 10 Archery All 0 0 0 Athletics Combined Events 15 15 15 Athletics Jumps 10 15 15 Athletics Long Distance 3000m or greater 60 5 5 Athletics Middle Distance 800‐1500m 30 10 10 Athletics Sprint 400m or less 10 15 15 Athletics Throws 5 15 15 Automobile Sports All 5 0 0 Badminton Badminton 10 10 10 Bandy Bandy 5 10 10 Baseball Baseball 5 10 10 Basketball Basketball 10 10 10 Basketball 3 on 3 10 10 10 Basque Pelota Basque Pelota 5 5 5 Biathlon Biathlon 60 10 10 Billiards Sports All 0 0 0 Bobsleigh Bobsleigh 5 10 10 Bobsleigh Skeleton 0 10 10 Bodybuilding Bodybuilding 5 30 30 Bodybuilding Fitness 10 30 30 Boules Sports All 0 0 0 Bowling All 0 0 0 Boxing Boxing 15 10 10 Bridge Bridge 0 0 0 4 Compliance with the GHRFs MLAs and GH MLAs will be mandatory from 1 January 2017 and 1 January 2018 respectively. -

A History of Synchronized Swimming1

Wir empfehlen Ihnen, auf einem Blatt jeweils zwei Seiten dieses Artikels nebeneinander auszudrucken. We recommend that you print two pages of this article side by side on one sheet. Body Politics 2 (2014), Heft 3, S. 21-38 A History of Synchronized Swimming1 Synthia Sydnor 2 Proem No fish, no fowl, nor other creature whatsoever that hath any living or being, wither in the depth of the sea or superficies of the water, swimmeth 3 upon his back, man only excepted. From articles-fragments-scrounging-primary evidence-sources-refer- ences-facts-propaganda4 (the above quotation dated 1595 is the earliest of my fragments), I assemble here a history of synchronized swimming, or at the least, I compose an essay in which I ponder synchronized swimming at the same time as I tread against the flow5 of the established methodology of “sport history” Historians take unusual pains to erase the elements in their work which reveal their grounding in a particular time and place, their preferences in a controversy – the unavoidable obstacles of their passions. … The genealogist … must be able to recognize the events of history, its jolts, its surprises, its unsteady victories and unpalatable defeats – the basis of all beginnings, atavisms and heredities. … Genealogy does not resemble the evolution of a species and does not map the destiny of a people. [It] identif[ies] the accidents, the minute deviations – or conversely – the complete reversals – the errors, the false appraisals, and the faulty calculations that gave birth to those things that continue to exist and have value for us.6 On genealogy, historical methodology, “items” and “pondering,” I am influenced by Walter Benjamin. -

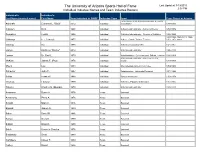

The University of Arizona Sports Hall of Fame Last Updated: 3/19/2015 2:58 PM Individual Inductee Names and Team Inductee Rosters

The University of Arizona Sports Hall of Fame Last Updated: 3/19/2015 2:58 PM Individual Inductee Names and Team Inductee Rosters Individual's Individual's Last Name (married name) First Name Year Inducted in SHOF Inductee Type Sport Years Played at Arizona Letterwinner & UA Athletics Facilities & Events Ashcraft Clarence L. "Stub" 2012 Individual Coordinator 1947-1982 Clausen Dick 1998 Individual Athletics Administrator - Athletics Director 1958-1972 Dempsey Cedric 1994 Individual Athletics Administrator - Director of Athletics 1982-1883 1924-1926, 1926-1941, 1926- Gibbings F.T. (Limey) 1977 Individual Athlete, Coach, Trainer, Teacher 1951, 1951-1969 Gittings Ina 1976 Individual Athletics Association (W) 1921-1951 Larose Kathleen "Rocky" 2014 Individual Athletics Administrator 1980-2013 Larson Dr. Emil L. 1979 Individual Administration - Commissioner, Official, Teacher 1926-1968 Athletics Administrator - Athletics Director, McKale James F. (Pop) 1976 Individual Coach 1914-1957 Myers Lou 1984 Individual Intercollegiate Athletic Committee 1959-1980 Schaefer John P. 1997 Individual Administraion - University President 1971-1982 Soltys Frank W. 1988 Individual Sports Information 1959-1979 Thomas Edward 1990 Individual Athletics - Equipment Manager 1951-1985 Tribolet Charles S. (Bumps) 1978 Individual Athletics Administrator 1928-1978 Anderson Burce H. 1976 Team Baseball Armstrong Perry A. 1976 Team Baseball Arnold Mark C. 1976 Team Baseball Bagnall James A. 1980 Team Baseball Baker David M. 1986 Team Baseball Bargar Greg R. 1980 Team Baseball Billard Brian R. 1980 Team Baseball Bolek Kenneth Charles 1976 Team Baseball Bradshaw Scott 1980 Team Baseball Candaele Casey T. 1980 Team Baseball Carley David 1986 Team Baseball The University of Arizona Sports Hall of Fame Last Updated: 3/19/2015 2:58 PM Individual Inductee Names and Team Inductee Rosters Individual's Individual's Last Name (married name) First Name Year Inducted in SHOF Inductee Type Sport Years Played at Arizona Carlsen Robin A. -

Sport Development Awards : Award Recipients 1987-2019

Sport Development Awards Award Recipients 1987-2019 Don Watts Coach Developer Award Coach Developer Award - Sport 2013 Don McGavern – Multi Sport 2013 Phyllis Sadoway – Ringette 2015 Leigh Gouldie – Multi Sport 2015 Beth Veale – Ringette 2017 Jim Loughlin – Multi Sport 2017 Kelly Wills – Artistic Gymnastics 2019 Susan Yackulic – Multi Sport 2019 Jacqueline Cool - Swimming Coaching Recognition Award 1987 1988 Dave Johnson – Swimming John Cannon - Athletics Ian Paton – Squash George Kingston - Hockey Perry Pearn – Hockey Glenn Purych - Wrestling Deryk Snelling – Swimming Yosh Senda - Judo Cathy Walsh – Wheelchair Stuart Brown - Soccer 1989 1990 Peter Connellan – Football Herb Flewwelling - Diving Michael Jiranek - Figure Skating Max Gartner - Alpine Skiing Carole Larsen – Curling Les Gramantik - Athletics Leslie Sproule - Synchronized Swimming Paul Hortie* - Boxing Milan Uremovic – Rowing Donna Rudakas - Basketball 1991 1992 Greg Folk - Figure Skating Ritch Braun - Athletics Bruce Rimmer - Alpine Skiing Bert Goldberger - Soccer Garry Smith - Wheelchair Basketball Dru Marshall - Field Hockey Sandy Teel - Synchronized Swimming Jan Ullmark - Figure Skating Sharon Trenaman - Squash April 2021 Classification: Public Coaching Recognition Award 1995 1997 Michelle Callkins - Synchronized Swimming Lynne Koper - Figure Skating Ewan Ferrier - Bowhunting and Archery Krysztof Machnowski - Sailing Patricia Foster – Rollerskating Jules Owchar - Colleges Winnifred Silverthorne - Figure Skating Channarong Ratanseangsuang - Badminton Jack Walters - Speed -

Table of Contents 2006 - 07 Schedule

2006 - 2007 S ta N ford S YN C H ro N I ZE D swimmi N G Table of Contents 2006 - 07 Schedule ..................... Inside Front Cover Quick Facts ............................................................... 3 Avery Aquatic Center The Stanford Student .............................................. 4 Sports Medicine ....................................................... 6 The recently rebuilt and remodeled 2006-07 Season Preview .......................................... 7 Avery Aquatic Center is home to Head Coach Heather Olson .................................... 8 Stanford water polo, swiming and Assistant Coaches ..................................................... 9 diving, and women’s synchronized Stanford Synchro History ...................................... 10 swimming. It is widely regarded as the Synchro All-Americans ................ ......................... 10 finest outdoor facility in the United 2005-06 Season Recap ............................................ 11 States, and one of the best in the world. Team Roster ............................................................ 13 One of the highlights of the facility is a Team Profiles .................................................... 14-19 37-meter and 14-feet deep competition Home of Champions ............................................. 20 pool, which can seat 2,530 spectators in Directors Cup ......................................................... 22 a stadium-like setting. The facility also Stanford Olympians .............................................. -

Sports Rights Catalogue 2017/2018

OPERATING EUROVISION AND EURORADIO SPORTS RIGHTS CATALOGUE 2017/2018 1 ABOUT US The EBU is the world’s foremost alliance of The core of our operation is the acquisition Flexible and business orientated are traits public service media organizations, with and distribution of media rights. We work with which perfectly complement the EBU’s well members in 56 countries in Europe and more than 30 federations on a continually established and highly effective distribution beyond. renewable sports rights portfolio consisting of model on a European and Worldwide basis. football, athletics, cycling, skiing, swimming The EBU’s mission is to safeguard the interests and many more. We are proud to collaborate Smart business thinking and commitment to of public service media and to promote their with elite federations such as FIFA*, UEFA*, innovation means the EBU is a key component indispensable contribution to modern society. IAAF, EAA, UCI, FINA, LEN, FIS, IPC, to name at all stages of the broadcast value chain. The a few. EBU is the ideal one-stop-shop partner for the Under the alias, EUROVISION, the EBU broadcast community. produces and distributes top-quality live In 2011, EBU created the Sales Unit to enhance sports and news, as well as entertainment, its competitiveness in an ever-evolving and * EBU Football contracts with FIFA and UEFA are culture and music content. Through extremely challenging industry. The Unit directly handled by the EBU Football Unit. EUROVISION, the EBU provides broadcasters handles the commercial distribution of sports with on-site facilities and services for major rights in EBU’s portfolio in not only European world events in news, sport and culture. -

AQUATICS: History of Synchronized Swimming at the Olympic Games

OSC REFERENCE COLLECTION AQUATICS History of Synchronized Swimming at the Olympic Games 19.10.2017 AQUATICS History of Synchronized Swimming at the Olympic Games SYNCHRONIZED SWIMMING Atlanta 1996 Beijing 2008 London 2012 Rio 2016 Synchronized Swimming (W) Synchronized swimming (W) Synchronized swimming (W) Synchronized swimming (W) INTRODUCTION It was at the Games of the XXIII Olympiad in Los Angeles in 1984, that synchronized swimming made its appearance on the Olympic programme with two events (solo and duet). The programme remained the same for the Games until Barcelona in 1992, while in Atlanta in 1996, a single team event was organised. Since the Games in Sydney in 2000, synchronized swimming has been comprised of two events: team and duet. KEY STAGES Entry 1980: At the 83rd IOC Session held in Moscow in July and August, it was decided to add synchronized swimming (with one duet event) to the programme of the Games of the XXIII Olympiad in Los Angeles in 1984. Solo 1984: At the IOC Executive Board meeting held in May in Lausanne, it was decided to add a solo event to the programme of the Games of the XXIII Olympiad in Los Angeles in 1984. Team event 1991: At the 97th IOC Session held in June in Birmingham (UK), it was decided to replace the solo and duet events with a team event. Duet 1997: At the 106th IOC Session held in Lausanne in September, it was decided to re-introduce the duet event. EVOLUTION IN THE NUMBER OF EVENTS / TEAMS 1984: 2 events (solo and 18 duets) 1996: 1 event (8 teams) 1988: 2 events (solo and 15 duets) 2000-2020: -

List of Sports

List of sports The following is a list of sports/games, divided by cat- egory. There are many more sports to be added. This system has a disadvantage because some sports may fit in more than one category. According to the World Sports Encyclopedia (2003) there are 8,000 indigenous sports and sporting games.[1] 1 Physical sports 1.1 Air sports Wingsuit flying • Parachuting • Banzai skydiving • BASE jumping • Skydiving Lima Lima aerobatics team performing over Louisville. • Skysurfing Main article: Air sports • Wingsuit flying • Paragliding • Aerobatics • Powered paragliding • Air racing • Paramotoring • Ballooning • Ultralight aviation • Cluster ballooning • Hopper ballooning 1.2 Archery Main article: Archery • Gliding • Marching band • Field archery • Hang gliding • Flight archery • Powered hang glider • Gungdo • Human powered aircraft • Indoor archery • Model aircraft • Kyūdō 1 2 1 PHYSICAL SPORTS • Sipa • Throwball • Volleyball • Beach volleyball • Water Volleyball • Paralympic volleyball • Wallyball • Tennis Members of the Gotemba Kyūdō Association demonstrate Kyūdō. 1.4 Basketball family • Popinjay • Target archery 1.3 Ball over net games An international match of Volleyball. Basketball player Dwight Howard making a slam dunk at 2008 • Ball badminton Summer Olympic Games • Biribol • Basketball • Goalroball • Beach basketball • Bossaball • Deaf basketball • Fistball • 3x3 • Footbag net • Streetball • • Football tennis Water basketball • Wheelchair basketball • Footvolley • Korfball • Hooverball • Netball • Peteca • Fastnet • Pickleball -

Physiological Responses and Competitive Performance in Elite Synchronized Swimming

Physiological responses and competitive performance in elite synchronized swimming Lara Rodríguez Zamora ADVERTIMENT. La consulta d’aquesta tesi queda condicionada a l’acceptació de les següents condicions d'ús: La difusió d’aquesta tesi per mitjà del servei TDX (www.tdx.cat) i a través del Dipòsit Digital de la UB (diposit.ub.edu) ha estat autoritzada pels titulars dels drets de propietat intel·lectual únicament per a usos privats emmarcats en activitats d’investigació i docència. No s’autoritza la seva reproducció amb finalitats de lucre ni la seva difusió i posada a disposició des d’un lloc aliè al servei TDX ni al Dipòsit Digital de la UB. No s’autoritza la presentació del seu contingut en una finestra o marc aliè a TDX o al Dipòsit Digital de la UB (framing). Aquesta reserva de drets afecta tant al resum de presentació de la tesi com als seus continguts. En la utilització o cita de parts de la tesi és obligat indicar el nom de la persona autora. ADVERTENCIA. La consulta de esta tesis queda condicionada a la aceptación de las siguientes condiciones de uso: La difusión de esta tesis por medio del servicio TDR (www.tdx.cat) y a través del Repositorio Digital de la UB (diposit.ub.edu) ha sido autorizada por los titulares de los derechos de propiedad intelectual únicamente para usos privados enmarcados en actividades de investigación y docencia. No se autoriza su reproducción con finalidades de lucro ni su difusión y puesta a disposición desde un sitio ajeno al servicio TDR o al Repositorio Digital de la UB. -

Redalyc.Age of Peak Performance in Olympic Sports: a Comparative

Journal of Human Sport and Exercise E-ISSN: 1988-5202 [email protected] Universidad de Alicante España LONGO, ALDO F.; SIFFREDI, CARLOS R.; CARDEY, MARCELO L.; AQUILINO, GUSTAVO D.; LENTINI, NÉSTOR A. Age of peak performance in Olympic sports: A comparative research among disciplines Journal of Human Sport and Exercise, vol. 11, núm. 1, 2016, pp. 31-41 Universidad de Alicante Alicante, España Available in: http://www.redalyc.org/articulo.oa?id=301049620003 How to cite Complete issue Scientific Information System More information about this article Network of Scientific Journals from Latin America, the Caribbean, Spain and Portugal Journal's homepage in redalyc.org Non-profit academic project, developed under the open access initiative Original Article Age of peak performance in Olympic sports: A comparative research among disciplines ALDO F. LONGO 1 , CARLOS R. SIFFREDI 2, MARCELO L. CARDEY 1, GUSTAVO D. AQUILINO 1, NÉSTOR A. LENTINI 1 1 Exercise Physiology Laboratory, National Center of High Performance Athletics (CeNARD), Buenos Aires, Argentina 2 National Entity of High Performance Athletics (ENARD), Buenos Aires, Argentina ABSTRACT Longo, A.F., Siffredi, C.R., Cardey, M.L., Aquilino, G.D., & Lentini, N.A. (2016). Age of peak performance in Olympic sports: A comparative research among disciplines. J. Hum. Sport Exerc., 11(1), 31-41. This research aimed to study the ages of peak performance in Olympic sport disciplines, and to distinguish age groups among them. The ages (in decimal years) of athletes with the best performances at the 2012 Summer Olympics were considered (n = 3548). A total of forty sport disciplines were included; the athletics events were classified in six disciplines: Sprint, Middle-distance, Long-distance, Combined, Jumping and Throwing.