Contextualizing My Self-Idiom

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Temporal Disunity and Structural Unity in the Music of John Coltrane 1965-67

Listening in Double Time: Temporal Disunity and Structural Unity in the Music of John Coltrane 1965-67 Marc Howard Medwin A dissertation submitted to the faculty of the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Department of Music. Chapel Hill 2008 Approved by: David Garcia Allen Anderson Mark Katz Philip Vandermeer Stefan Litwin ©2008 Marc Howard Medwin ALL RIGHTS RESERVED ii ABSTRACT MARC MEDWIN: Listening in Double Time: Temporal Disunity and Structural Unity in the Music of John Coltrane 1965-67 (Under the direction of David F. Garcia). The music of John Coltrane’s last group—his 1965-67 quintet—has been misrepresented, ignored and reviled by critics, scholars and fans, primarily because it is a music built on a fundamental and very audible disunity that renders a new kind of structural unity. Many of those who study Coltrane’s music have thus far attempted to approach all elements in his last works comparatively, using harmonic and melodic models as is customary regarding more conventional jazz structures. This approach is incomplete and misleading, given the music’s conceptual underpinnings. The present study is meant to provide an analytical model with which listeners and scholars might come to terms with this music’s more radical elements. I use Coltrane’s own observations concerning his final music, Jonathan Kramer’s temporal perception theory, and Evan Parker’s perspectives on atomism and laminarity in mid 1960s British improvised music to analyze and contextualize the symbiotically related temporal disunity and resultant structural unity that typify Coltrane’s 1965-67 works. -

Expanding Horizons: the International Avant-Garde, 1962-75

452 ROBYNN STILWELL Joplin, Janis. 'Me and Bobby McGee' (Columbia, 1971) i_ /Mercedes Benz' (Columbia, 1971) 17- Llttle Richard. 'Lucille' (Specialty, 1957) 'Tutti Frutti' (Specialty, 1955) Lynn, Loretta. 'The Pili' (MCA, 1975) Expanding horizons: the International 'You Ain't Woman Enough to Take My Man' (MCA, 1966) avant-garde, 1962-75 'Your Squaw Is On the Warpath' (Decca, 1969) The Marvelettes. 'Picase Mr. Postman' (Motown, 1961) RICHARD TOOP Matchbox Twenty. 'Damn' (Atlantic, 1996) Nelson, Ricky. 'Helio, Mary Lou' (Imperial, 1958) 'Traveling Man' (Imperial, 1959) Phair, Liz. 'Happy'(live, 1996) Darmstadt after Steinecke Pickett, Wilson. 'In the Midnight Hour' (Atlantic, 1965) Presley, Elvis. 'Hound Dog' (RCA, 1956) When Wolfgang Steinecke - the originator of the Darmstadt Ferienkurse - The Ravens. 'Rock All Night Long' (Mercury, 1948) died at the end of 1961, much of the increasingly fragüe spirit of collegial- Redding, Otis. 'Dock of the Bay' (Stax, 1968) ity within the Cologne/Darmstadt-centred avant-garde died with him. Boulez 'Mr. Pitiful' (Stax, 1964) and Stockhausen in particular were already fiercely competitive, and when in 'Respect'(Stax, 1965) 1960 Steinecke had assigned direction of the Darmstadt composition course Simón and Garfunkel. 'A Simple Desultory Philippic' (Columbia, 1967) to Boulez, Stockhausen had pointedly stayed away.1 Cage's work and sig- Sinatra, Frank. In the Wee SmallHoun (Capítol, 1954) Songsfor Swinging Lovers (Capítol, 1955) nificance was a constant source of acrimonious debate, and Nono's bitter Surfaris. 'Wipe Out' (Decca, 1963) opposition to himz was one reason for the Italian composer being marginal- The Temptations. 'Papa Was a Rolling Stone' (Motown, 1972) ized by the Cologne inner circle as a structuralist reactionary. -

A More Attractive ‘Way of Getting Things Done’ Freedom, Collaboration and Compositional Paradox in British Improvised and Experimental Music 1965-75

A more attractive ‘way of getting things done’ freedom, collaboration and compositional paradox in British improvised and experimental music 1965-75 Simon H. Fell A thesis submitted to the University of Huddersfield in fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy The University of Huddersfield September 2017 copyright statement i. The author of this thesis (including any appendices and/or schedules to this thesis) owns any copyright in it (the “Copyright”) and he has given The University of Huddersfield the right to use such Copyright for any administrative, promotional, educational and/or teaching purposes. ii. Copies of this thesis, either in full or in extracts, may be made only in accordance with the regulations of the University Library. Details of these regulations may be obtained from the Librarian. This page must form part of any such copies made. iii. The ownership of any patents, designs, trade marks and any and all other intellectual property rights except for the Copyright (the “Intellectual Property Rights”) and any reproductions of copyright works, for example graphs and tables (“Reproductions”), which may be described in this thesis, may not be owned by the author and may be owned by third parties. Such Intellectual Property Rights and Reproductions cannot and must not be made available for use without the prior written permission of the owner(s) of the relevant Intellectual Property Rights and/or Reproductions. 2 abstract This thesis examines the activity of the British musicians developing a practice of freely improvised music in the mid- to late-1960s, in conjunction with that of a group of British composers and performers contemporaneously exploring experimental possibilities within composed music; it investigates how these practices overlapped and interpenetrated for a period. -

Final Thesis.Pdf

An Investigation of the Impact of Ensemble Interrelationship on Performances of Improvised Music Through Practice Research by Sarah Gail Brand Canterbury Christ Church University Thesis submitted for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy 2019 Abstract In this thesis I present my investigation into the ways in which the creative and social relationships I have developed with long-term collaborators alter or affect the musical decisions I make in my performances of Improvised Music. The aim of the investigation has been to deepen the understanding of my musical and relational processes as a trombonist through the examination of my artistic practice, which is formed by experiences in range of genres such as Jazz and contemporary music, with a current specialty in Improvised Music performance. By creating an interpretative framework from the theoretical and analytical processes used in music therapy practice, I have introduced a tangible set of concepts that can interpret my Improvised Music performance processes and establish objective perspectives of subjective musical experiences. Chapter one is concerned with recent debates in Improvised Music and music therapy. Particular reference is made to literature that considers interplay between performers. Chapter two focuses on my individual artistic practice and examines the influence of five trombone players from Jazz and Improvised Music performance on my praxis. A recording of one of my solo trombone performances accompanies this section. It concludes with a discussion on my process of making tacit knowledge of Improvised Music performance tangible and explicit and the abstruse nature of subjective feeling states when performing improvisation. This concludes part one of the thesis. -

Solo List and Reccomended List for 02-03-04 Ver 3

Please read this before using this recommended guide! The following pages are being uploaded to the OSSAA webpage STRICTLY AS A GUIDE TO SOLO AND ENSEMBLE LITERATURE. In 1999 there was a desire to have a required list of solo and ensemble literature, similar to the PML that large groups are required to perform. Many hours were spent creating the following document to provide “graded lists” of literature for every instrument and voice part. The theory was a student who made a superior rating on a solo would be required to move up the list the next year, to a more challenging solo. After 2 years of debating the issue, the music advisory committee voted NOT to continue with the solo/ensemble required list because there was simply too much music written to confine a person to perform from such a limited list. In 2001 the music advisor committee voted NOT to proceed with the required list, but rather use it as “Recommended Literature” for each instrument or voice part. Any reference to “required lists” or “no exceptions” in this document need to be ignored, as it has not been updated since 2001. If you have any questions as to the rules and regulations governing solo and ensemble events, please refer back to the OSSAA Rules and Regulation Manual for the current year, or contact the music administrator at the OSSAA. 105 SOLO ENSEMBLE REGULATIONS 1. Pianos - It is recommended that you use digital pianos when accoustic pianos are not available or if it is most cost effective to use a digital piano. -

Jazz Woodwind Syllabus

Jazz Woodwind Syllabus Flute, Clarinet & Saxophone Grade exams 2017–2022 Important information Changes from the previous syllabus Repertoire lists for all instruments have been updated. Own composition requirements have been revised. Aural test parameters have been revised, and new specimen tests publications are available. Improvisation test requirements have changed, and new preparation materials are available on our website. Impression information Candidates should refer to trinitycollege.com/woodwind to ensure that they are using the latest impression of the syllabus. Digital assessment: Digital Grades and Diplomas To provide even more choice and flexibility in how Trinity’s regulated qualifications can be achieved, digital assessment is available for all our classical, jazz and Rock & Pop graded exams, as well as for ATCL and LTCL music performance diplomas. This enables candidates to record their exam at a place and time of their choice and then submit the video recording via our online platform to be assessed by our expert examiners. The exams have the same academic rigour as our face-to-face exams, and candidates gain full recognition for their achievements, with the same certificate and UCAS points awarded as for the face-to-face exams. Find out more at trinitycollege.com/dgd photo: Zute Lightfoot, clarinet courtesy of Yamaha Music London Jazz Woodwind Syllabus Flute, Clarinet & Saxophone Graded exams 2017–2022 Trinity College London trinitycollege.com Charity number England & Wales: 1014792 Charity number Scotland: SC049143 Patron: HRH The Duke of Kent KG Chief Executive: Sarah Kemp Copyright © 2016 Trinity College London Published by Trinity College London Online edition, March 2021 Contents Introduction ....................................................................................................................... -

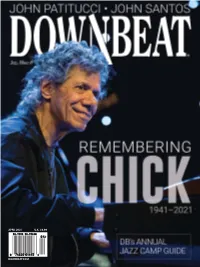

Downbeat.Com April 2021 U.K. £6.99

APRIL 2021 U.K. £6.99 DOWNBEAT.COM April 2021 VOLUME 88 / NUMBER 4 President Kevin Maher Publisher Frank Alkyer Editor Bobby Reed Reviews Editor Dave Cantor Contributing Editor Ed Enright Creative Director ŽanetaÎuntová Design Assistant Will Dutton Assistant to the Publisher Sue Mahal Bookkeeper Evelyn Oakes ADVERTISING SALES Record Companies & Schools Jennifer Ruban-Gentile Vice President of Sales 630-359-9345 [email protected] Musical Instruments & East Coast Schools Ritche Deraney Vice President of Sales 201-445-6260 [email protected] Advertising Sales Associate Grace Blackford 630-359-9358 [email protected] OFFICES 102 N. Haven Road, Elmhurst, IL 60126–2970 630-941-2030 / Fax: 630-941-3210 http://downbeat.com [email protected] CUSTOMER SERVICE 877-904-5299 / [email protected] CONTRIBUTORS Senior Contributors: Michael Bourne, Aaron Cohen, Howard Mandel, John McDonough Atlanta: Jon Ross; Boston: Fred Bouchard, Frank-John Hadley; Chicago: Alain Drouot, Michael Jackson, Jeff Johnson, Peter Margasak, Bill Meyer, Paul Natkin, Howard Reich; Indiana: Mark Sheldon; Los Angeles: Earl Gibson, Sean J. O’Connell, Chris Walker, Josef Woodard, Scott Yanow; Michigan: John Ephland; Minneapolis: Andrea Canter; Nashville: Bob Doerschuk; New Orleans: Erika Goldring, Jennifer Odell; New York: Herb Boyd, Bill Douthart, Philip Freeman, Stephanie Jones, Matthew Kassel, Jimmy Katz, Suzanne Lorge, Phillip Lutz, Jim Macnie, Ken Micallef, Bill Milkowski, Allen Morrison, Dan Ouellette, Ted Panken, Tom Staudter, Jack Vartoogian; Philadelphia: Shaun Brady; Portland: Robert Ham; San Francisco: Yoshi Kato, Denise Sullivan; Seattle: Paul de Barros; Washington, D.C.: Willard Jenkins, John Murph, Michael Wilderman; Canada: J.D. Considine, James Hale; France: Jean Szlamowicz; Germany: Hyou Vielz; Great Britain: Andrew Jones; Portugal: José Duarte; Romania: Virgil Mihaiu; Russia: Cyril Moshkow. -

'The Construction and Application of A

Experimental Music Catalogue: Article Archive The following is one of a number of articles, speeches, and documents that may be of use to the experimental music scholar. Permission is granted to quote short passages of the following article in publication, as long as credit is given to the author. For full reproduction and other uses, please contact the Experimental Music Catalogue at [email protected]. The Construction and Application of a Model for the Analysis of Linear Free Improvised Music Bruce Coates MA This is a more or less unvarnished version of a paper that I initially presented at The 4th European Music Analysis Conference, Rotterdam in 1999 and again in a slightly altered form at De Montfort University in 2000. It sets out my first attempts to device a system to analyse what Derek Bailey once described as the un- analysable (Wittgenstinians I know what you’re thinking!). It is a much-reduced version of my Masters thesis, which I completed at De Montfort University in 1998 (if anyone is interested in seeing more feel free to contact me). Inevitably, my thinking has moved on since writing this and quite a lot of what I wrote then now seems naive (one reason why I haven’t tried to alter the paper). However, I present it here because I feel that it contains some useful ideas about a still largely neglected area of study. Bruce Coates 2002 Abstract THE ANALYSIS of Free Improvised music is uncommon perhaps because it does not have a set of agreed rules from which it may be said to adhere or deviate. -

A History of Electronic Music Pioneers David Dunn

A HISTORY OF ELECTRONIC MUSIC PIONEERS DAVID DUNN D a v i d D u n n “When intellectual formulations are treated simply renewal in the electronic reconstruction of archaic by relegating them to the past and permitting the perception. simple passage of time to substitute for development, It is specifically a concern for the expansion of the suspicion is justified that such formulations have human perception through a technological strate- not really been mastered, but rather they are being gem that links those tumultuous years of aesthetic suppressed.” and technical experimentation with the 20th cen- —Theodor W. Adorno tury history of modernist exploration of electronic potentials, primarily exemplified by the lineage of “It is the historical necessity, if there is a historical artistic research initiated by electronic sound and necessity in history, that a new decade of electronic music experimentation beginning as far back as television should follow to the past decade of elec- 1906 with the invention of the Telharmonium. This tronic music.” essay traces some of that early history and its —Nam June Paik (1965) implications for our current historical predicament. The other essential argument put forth here is that a more recent period of video experimentation, I N T R O D U C T I O N : beginning in the 1960's, is only one of the later chapters in a history of failed utopianism that Historical facts reinforce the obvious realization dominates the artistic exploration and use of tech- that the major cultural impetus which spawned nology throughout the 20th century. video image experimentation was the American The following pages present an historical context Sixties. -

U.S. Sheet Music Collection

U.S. SHEET MUSIC COLLECTION SUB-GROUP I, SERIES 4, SUB-SERIES B (VOCAL) Consists of vocal sheet music published between 1861 and 1890. Titles are arranged in alphabetical order by surname of known composer or arranger; anonymous compositions are inserted in alphabetical order by title. ______________________________________________________________________________ Box 181 Abbot, Jno. M. Gently, Lord! Oh, Gently Lead Us. For Soprano Solo and Quartette. Harmonized and adapted from a German melody. Troy, NY: C. W. Harris, 1867. Abbot, John M. God Is Love. Trio for Soprano, Tenor, and Basso. Adapted from Conradin Kreutzer. New York: Wm. A. Pond & Co., 1865. Abbot, John M. Hear Our Prayer. Trio for Soprano, Contralto, and Basso. Brooklyn: Alphonzo Smith, 1862. Abbot, John M. Hear Our Prayer. Trio for Soprano, Contralto, and Basso. Brooklyn: Charles C. Sawyer, 1862. 3 copies. Abbot, John M. Hear Our Prayer. Trio for Soprano, Contralto, and Basso. Brooklyn: J. W. Smith, Jr., 1862. 3 copies. Abbot, John M. Softly now the light of day. Hymn with solos for Soprano, Tenor, and Contralto or Baritone. New York: S. T. Gordon, 1866. Abbott, Jane Bingham. Just For To-Day. Sacred Song for Soprano. Words by Samuel Wilberforce. Chicago: Clayton F. Summy Co., 1894. Abraham’s Daughter; or, Raw Recruits. For voice and piano. New York: Firth, Pond & Co., 1862. Cover features lithograph printed by Sarony, Major & Knapp. Abt, Franz. Absence and Return. For voice and piano. Words by J. E. Carpenter, PhD. From “New Songs by Franz Abt.” Boston: Oliver Ditson & Co., [s.d.]. Abt, Franz. Autumnal Winds (Es Braust der Herbstwind). Song for Soprano or Tenor in D Minor. -

The University of North Carolina at Wilmington Department of Music

The University of North Carolina at Wilmington Department of Music SELECT SAXOPHONE REPERTOIRE & LEVELS First Year Method Books: The Saxophonist’s Workbook (Larry Teal) Foundation Studies (David Hite) Saxophone Scales & Patterns (Dan Higgins) Preparatory Method for Saxophone (George Wolfe) Top Tones for the Saxophone (Eugene Rousseau) Saxophone Altissimo (Robert Luckey) Intonation Exercises (Jean-Marie Londeix) Exercises: The following should be played at a minimum = 120 q • Major scales, various articulations • Single tongue on one note • Major thirds • Alternate fingerings (technique & intonation) • Single tongue on scale excerpt, tonic to dominant • Harmonic minor scales • Chromatic scale • Arpeggios in triads Vibrato (minimum = 108 for 3/beat or = 72-76 for 4/beat) q q Overtones & altissimo Jazz articulation Etude Books: 48 Etudes (Ferling/Mule) Selected Studies (Voxman) 53 Studies, Book I (Marcel Mule) 25 Daily Exercises (Klose) 50 Etudes Faciles & Progressives, I & II (Guy Lacour) 15 Etudes by J.S. Bach (Caillieret) The Orchestral Saxophonist (Ronkin/Frascotti) Rubank Intermediate and/or Advanced Method (Voxman) Select Solos: Alto Solos for Alto Saxophone (arr. by Larry Teal) Aria (Eugene Bozza) Sicilienne (Pierre Lantier) Dix Figures a Danser (Pierre-Max Dubois) Sonata (Henri Eccles/Rasher) Sonata No. 3 (G.F. Handel/Rascher) Adagio & Allegro (G.F. Handel/Gee) Three Romances, alto or tenor (Robert Schumann) Sonata (Paul Hindemith) 1 A la Francaise (P.M. Dubois) Tenor Solo Album (arr. by Eugene Rousseau) 7 Solos for Tenor Saxophone -

Jurisgenerative Grammar (For Alto)

JURISGENERATIVE GRAMMAR 129 Cover reveals the constituted indispensability of the legal system as an institutional CHAPTER 6 analog of the understanding designed to curtail the lawless freedom with which laws are generated and subsequently argues for the duty to resist legal system, even if from ········································································································ within it, in its materialization in and as the state. In the concluding paragraph of his unfinished final article "The Bonds of Constitutional Interpretation: Of the Word, the JURISGENERATIVE GRAMMAR Deed, and the Role;' he argues that "in law to be an interpreter is to be a force, an actor who creates effects even through or in the face of violence. To stop short of suffering or (FOR ALTO) imposing violence is to give law up to tho se who are willing to so act. The state is orga nized to overcome scruple and fear. Its officiais will so act. All others are merely peti ········································································································ tioners if they will not fight back:'2 But insofar as sorne of us ding to Samuel Beckett's notion that "the thing to avoid ... is the spirit of system;' we are left to wonder how else FRED MOTEN and where else the resistance of the jurisgenerative multitude is constituted. 3 Moreover, we are required to consider an interarticulate relationship between flight and fight that American jurisprudence can hardly fa thom. That man was not meant torun away is, for Oliver Wendell