Joseph Kreines and His Music for Alto Saxophone: a Biography, Analysis, and Performance Guide

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Flute Music of Yuko Uebayashi

THE FLUTE MUSIC OF YUKO UEBAYASHI: ANALYTIC STUDY AND DISCUSSION OF SELECTED WORKS by PEI-SAN CHIU Submitted to the faculty of the Jacobs School of Music in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree, Doctor of Music Indiana University July 2016 Accepted by the faculty of the Indiana University Jacobs School of Music, in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree Doctor of Music Doctoral Committee ______________________________________ Thomas Robertello, Research Director ______________________________________ Don Freund ______________________________________ Kathleen McLean ______________________________________ Linda Strommen June 14, 2016 ii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS Thanks to my flute professor Thomas Robertello for his guidance as a research director and as mentor during my study in Indiana University. My appreciation and gratitude also expressed to the committee members: Prof. Kathleen McLean, Prof. Linda Strommen and Dr. Don Freund for their time and suggestions. Special thanks to Ms. Yuko Uebayashi for sharing her music and insight, and being cooperative to make this document happen. Thanks to Prof. Emile Naoumoff and Jean Ferrandis for their coaching and share their role in the creation and performance of this study. Also,I would also like to thank the pianists: Mengyi Yang, Li-Ying Chang and Alber Chien. They have all contributed significantly to this project. Thanks to Alex Krawczyk for his kind and patient assistance for the editorial suggestion. Thanks to Satoshi Takagaki for his translation on the program notes. Finally, I would like to thank my parents Wan-Chuan Chiu and Su-Jen Lin for their constant encouragement and financial support, and also my dearest sister, I-Ping Chiu and my other half, Chen-Wei Wei, for everything. -

PRELUDE, FUGUE News for Friends of Leonard Bernstein RIFFS Spring/Summer 2004 the Leonard Bernstein School Improvement Model: More Findings Along the Way by Dr

PRELUDE, FUGUE News for Friends of Leonard Bernstein RIFFS Spring/Summer 2004 The Leonard Bernstein School Improvement Model: More Findings Along the Way by Dr. Richard Benjamin THE GRAMMY® FOUNDATION eonard Bernstein is cele brated as an artist, a CENTER FOP LEAR ll I IJ G teacher, and a scholar. His Lbook Findings expresses the joy he found in lifelong learning, and expounds his belief that the use of the arts in all aspects of education would instill that same joy in others. The Young People's Concerts were but one example of his teaching and scholarship. One of those concerts was devoted to celebrating teachers and the teaching profession. He said: "Teaching is probably the noblest profession in the world - the most unselfish, difficult, and hon orable profession. But it is also the most unappreciated, underrat Los Angeles. Devoted to improv There was an entrepreneurial ed, underpaid, and under-praised ing schools through the use of dimension from the start, with profession in the world." the arts, and driven by teacher each school using a few core leadership, the Center seeks to principles and local teachers Just before his death, Bernstein build the capacity in teachers and designing and customizing their established the Leonard Bernstein students to be a combination of local applications. That spirit Center for Learning Through the artist, teacher, and scholar. remains today. School teams went Arts, then in Nashville Tennessee. The early days in Nashville, their own way, collaborating That Center, and its incarnations were, from an educator's point of internally as well as with their along the way, has led to what is view, a splendid blend of rigorous own communities, to create better now a major educational reform research and talented expertise, schools using the "best practices" model, located within the with a solid reliance on teacher from within and from elsewhere. -

Foundation for Chinese Performing Arts 中華表演藝術基金會

中華表演藝術基金會 FOUNDATION FOR CHINESE PERFORMING ARTS [email protected] www.ChinesePerformingArts.net The Foundation for Chinese Performing Arts, is a non-profit organization registered in the Commonwealth of Massachusetts in January, 1989. The main objectives of the Foundation are: * To enhance the understanding and the appreciation of Eastern heritage through music and performing arts. * To promote Chinese music and performing arts through performances. * To provide opportunities and assistance to young Asian artists. The Founder and the President is Dr. Catherine Tan Chan 譚嘉陵. AWARDS AND SCHOLARSHIPS The Foundation held its official opening ceremony on September 23, 1989, at the Rivers School in Weston. Professor Chou Wen-Chung of Columbia University lectured on the late Alexander Tcherepnin and his contribution in promoting Chinese music. The Tcherepnin Society, represented by the late Madame Ming Tcherepnin, an Honorable Board Member of the Foundation, donated to the Harvard Yenching Library a set of original musical manuscripts composed by Alexander Tcherepnin and his student, Chiang Wen-Yeh. Dr. Eugene Wu, Director of the Harvard Yenching Library, was there to receive the gift that includes the original orchestra score of the National Anthem of the Republic of China commissioned in 1937 to Alexander Tcherepnin by the Chinese government. The Foundation awarded Ms. Wha Kyung Byun as the outstanding music educator. In early December 1989, the Foundation, recognized Professor Sylvia Shue-Tee Lee for her contribution in educating young violinists. The recipients of the Foundation's artist scholarship award were: 1989 Jindong Cai 蔡金冬, MM conductor ,New England Conservatory, NEC (currently conductor and Associate Professor of Music, Stanford University,) 1990: (late) Pei-Kun Xi, MM, conductor, NEC; 1991: pianists John Park and J.G. -

Chicago Symphony Orchestra Riccardo Muti Zell Music Director Yo-Yo Ma Judson and Joyce Green Creative Consultant Global Sponsor of the CSO

PROGRAM ONE HUNDRED TWENTY-FIFTH SEASON Chicago Symphony Orchestra Riccardo Muti Zell Music Director Yo-Yo Ma Judson and Joyce Green Creative Consultant Global Sponsor of the CSO Friday, February 5, 2016, at 8:00 Saturday, February 6, 2016, at 8:00 Gennady Rozhdestvensky Conductor Music by Dmitri Shostakovich Symphony No. 1 in F Minor, Op. 10 Allegretto—Allegro non troppo Allegro Lento—Largo—Lento Allegro molto—Lento INTERMISSION Symphony No. 15 in A Major, Op. 141 Allegretto Adagio Allegretto Adagio—Allegretto Saturday’s concert is sponsored by ITW. This program is partially supported by grants from the Illinois Arts Council, a state agency, and the National Endowment for the Arts. COMMENTS by Phillip Huscher Dmitri Shostakovich Born September 25, 1906, Saint Petersburg, Russia. Died August 9, 1975, Moscow, Russia. Symphony No. 1 in F Minor, Op. 10 In our amazement at a keen ear, a sharp musical memory, and great those rare talents who discipline—all the essential tools (except, per- mature early and die haps, for self-confidence and political savvy) for a young—Mozart, major career in the music world. His Symphony Schubert, and no. 1 is the first indication of the direction his Mendelssohn immedi- career would take. Written as a graduation thesis ately come to mind—we at the Saint Petersburg Conservatory, it brought often undervalue the less him international attention. In the years imme- spectacular accomplish- diately following its first performance in May ments of those who burst 1926, it made the rounds of the major orchestras, on the scene at a young age and go on to live beginning in this country with the Philadelphia long, full, musically rich lives. -

Solo List and Reccomended List for 02-03-04 Ver 3

Please read this before using this recommended guide! The following pages are being uploaded to the OSSAA webpage STRICTLY AS A GUIDE TO SOLO AND ENSEMBLE LITERATURE. In 1999 there was a desire to have a required list of solo and ensemble literature, similar to the PML that large groups are required to perform. Many hours were spent creating the following document to provide “graded lists” of literature for every instrument and voice part. The theory was a student who made a superior rating on a solo would be required to move up the list the next year, to a more challenging solo. After 2 years of debating the issue, the music advisory committee voted NOT to continue with the solo/ensemble required list because there was simply too much music written to confine a person to perform from such a limited list. In 2001 the music advisor committee voted NOT to proceed with the required list, but rather use it as “Recommended Literature” for each instrument or voice part. Any reference to “required lists” or “no exceptions” in this document need to be ignored, as it has not been updated since 2001. If you have any questions as to the rules and regulations governing solo and ensemble events, please refer back to the OSSAA Rules and Regulation Manual for the current year, or contact the music administrator at the OSSAA. 105 SOLO ENSEMBLE REGULATIONS 1. Pianos - It is recommended that you use digital pianos when accoustic pianos are not available or if it is most cost effective to use a digital piano. -

The Taiwanese Violin System: Educating Beginners to Professionals

University of Kentucky UKnowledge Theses and Dissertations--Music Music 2020 THE TAIWANESE VIOLIN SYSTEM: EDUCATING BEGINNERS TO PROFESSIONALS Yu-Ting Huang University of Kentucky, [email protected] Author ORCID Identifier: https://orcid.org/0000-0002-0469-9344 Digital Object Identifier: https://doi.org/10.13023/etd.2020.502 Right click to open a feedback form in a new tab to let us know how this document benefits ou.y Recommended Citation Huang, Yu-Ting, "THE TAIWANESE VIOLIN SYSTEM: EDUCATING BEGINNERS TO PROFESSIONALS" (2020). Theses and Dissertations--Music. 172. https://uknowledge.uky.edu/music_etds/172 This Doctoral Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Music at UKnowledge. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses and Dissertations--Music by an authorized administrator of UKnowledge. For more information, please contact [email protected]. STUDENT AGREEMENT: I represent that my thesis or dissertation and abstract are my original work. Proper attribution has been given to all outside sources. I understand that I am solely responsible for obtaining any needed copyright permissions. I have obtained needed written permission statement(s) from the owner(s) of each third-party copyrighted matter to be included in my work, allowing electronic distribution (if such use is not permitted by the fair use doctrine) which will be submitted to UKnowledge as Additional File. I hereby grant to The University of Kentucky and its agents the irrevocable, non-exclusive, and royalty-free license to archive and make accessible my work in whole or in part in all forms of media, now or hereafter known. -

Hung-Kuan Chen, Piano Boswell Recital Hall

中華表演藝術基金會 Foundation for Chinese Performing Arts The 17th Annual Music Festival at Walnut Hill Concerts and Master Class August 1 - 22, 2008 Except the August 20’s Esplanade Concert, all the events will be held at the Walnut Hill School, 12 Highland St. Natick, MA 01760. ($5 donation at door) Tuesday, August 12, 2008, 7:30 PM Hung-Kuan Chen, Piano Boswell Recital Hall Program Brahms: Op. 116 no.4 Beethoven: Sonata No. 28, Op. 101 Brahms: Variations on a Theme of Paganini Bartok: Out of Doors Suite Rachmaninoff: Sonata Allegro Agitato Non Allegro Allegro Molto Professor Hung-Kuan Chen 陳宏寬, pianist “Back in the ‘80’s, Apollo and Dionysus, Florestan and Eusebius, were at war in Chen’s pianistic personality. He could play with poetic insight, he could also erupt into an almost terrifying overdrive. But now there is the repose and the forces have been brought into complimentary harmony. ....This man plays music with uncommon understanding and the instrument with uncommon imagination!” Richard Dyer, Boston Globe. (January 1999) Mr. Hung-Kuan Chen is probably the most decorated pianist in Boston. He won the Gold Medals both in Arthur Rubinstein International Piano Master Competition in Israel and the Feruccio Busoni International Piano Competitions in Italy. He gathered prizes in Geza Anda, the Queen Elisabeth and the Chopin competitions and when the New York Times failed to cover Chen’s Alice Tully debut, after winning Young Concert Artists, Ruth Laredo in another NY publication exclaimed, “rarely have I heard such eloquence and musical understanding. Is anyone listening?” A true recitalist, he has performed in major venues worldwide. -

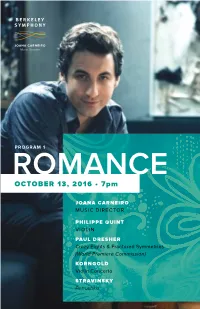

Berkeleysymphonyprogram2016

Mountain View Cemetery Association, a historic Olmsted designed cemetery located in the foothills of Oakland and Piedmont, is pleased to announce the opening of Piedmont Funeral Services. We are now able to provide all funeral, cremation and celebratory services for our families and our community at our 223 acre historic location. For our families and friends, the single site combination of services makes the difficult process of making funeral arrangements a little easier. We’re able to provide every facet of service at our single location. We are also pleased to announce plans to open our new chapel and reception facility – the Water Pavilion in 2018. Situated between a landscaped garden and an expansive reflection pond, the Water Pavilion will be perfect for all celebrations and ceremonies. Features will include beautiful kitchen services, private and semi-private scalable rooms, garden and water views, sunlit spaces and artful details. The Water Pavilion is designed for you to create and fulfill your memorial service, wedding ceremony, lecture or other gatherings of friends and family. Soon, we will be accepting pre-planning arrangements. For more information, please telephone us at 510-658-2588 or visit us at mountainviewcemetery.org. Berkeley Symphony 2016/17 Season 5 Message from the Music Director 7 Message from the Board President 9 Message from the Executive Director 11 Board of Directors & Advisory Council 12 Orchestra 14 Season Sponsors 18 Berkeley Symphony Legacy Society 21 Program 25 Program Notes 39 Music Director: Joana Carneiro 43 Artists’ Biographies 51 Berkeley Symphony 55 Music in the Schools 57 2016/17 Membership Benefits 59 Annual Membership Support 66 Broadcast Dates Mountain View Cemetery Association, a historic Olmsted designed cemetery located in the foothills of 69 Contact Oakland and Piedmont, is pleased to announce the opening of Piedmont Funeral Services. -

Jerona Music Catalogue

Triofor Violin,Guitar and Piano (1972). COLLECTIONS - MULTIPLE COMPOSERS violin, guitar, piano B02235 score 14.00 Album I.Compositions for Flute Solo (6) (includes works of Barkin, Frank,Gerber,Zuckerman,Rausch & Kreiger). B02236 playing scores (3) 35.00 B01171 solo flute 10.00 Album I.Compositions for Horn Solo (5) (includes works of Caclooppo, BOYKAN, Martin (b.1931) Williams,Pope & Rausch). Psalm 126. B01181 solo horn 13.00 B02435 mixed chorus a cappella 2.00 Album I.Compositions for Violin Solo (5) (includes works of Barkin, String Quartet No.2 (1974). Gerber,Lee,Philippot & Williams). string quartet B01121 solo violin 13.00 B02440 study score 10.00 Album I.Pieces for Viola Solo (5) (includes works of Krenek,Pollock & B02440 set of parts 73.00 Wright). Triofor Violin,Cello and Piano (1968). B01131 solo viola 13.00 violin, cello, piano Album I.Songs for Low Male Voiceand Piano (10) (includes works of B02445 study score 10.00 Hall,Hobson & Leibowitz). B02445 set of parts 68.00 B01191 voice, piano 12.00 Album II.Compositions for Cello Solo (7) (includes works of Edwards, BRAHMS, Johannes (1833-1897) Gerber,Peyton,Philippot,Williams,Winkler & Zuckerman). B01142 solo cello 13.00 Canons (13) for Women’s Voices,Op.113 (German). women’s choir a cappella Album II.Compositions for Violin Solo (4) (includes works of Leibowitz, C01006 choral score 3.00 Perle & Philippot). B01122 solo violin 13.00 BRUCKNER, Anton (1824-1896) Album III.Compositions for Cello Solo (2) (includes works of Casanova Psalm 112 (German). & Perle). double mixed chorus, orchestra B01143 solo cello 10.00 C01008 vocal score 8.00 Album IV.Compositions for Piano (3) (includes works of Edwards, score & parts (price on request) James & Winkler). -

A Brief History of the MSO

A Brief History of the MSO THE BIRTH OF AN ORCHESTRA T WAS A CHILLY JANUARY EVENING IN 1959, and members of the Board I of the Milwaukee Pops Orchestra were witnessing the climax of their most successful season to date. Six thousand and three hundred people crowded into the old Auditorium to watch the ensemble, led by a young conductor named Harry John Brown, perform in concert with a young Texan pianist named Van Cliburn. After ten years of ups and downs, the fledgling orchestra was experiencing the beginnings of stability. For more than a decade, under the baton of John Anello, the Milwaukee Pops Orchestra had grown and persevered. With the success of the 1958/59 season, the Directors — including President Stanley Williams, Judge Robert Landry, George Everitt and others — realized that they had come to a crossroads. In May of 1959, prior to the start of the 1959/60 season, the Board gathered in Judge Landry’s chambers, and the name of the ensemble was officially changed to Milwaukee Symphony Orchestra. The Board immediately hired Milwaukee public relations man Robert S. Zigman as the first business 1 Harry John Brown is appointed the MSO’s manager. Under Zigman’s skilled leadership, the establishment of the new orchestra progressed first music director. swiftly. On October 29, 1959, the MSO performed its first concert since assuming its new name, 2 Music Director Harry John Brown meets with Miss Gertrude Puelicher, founder of the under the direction of Arthur Fiedler. The first classical concert was performed on January 15, 1960, Milwaukee Symphony Women’s League, under the baton of Hans Schwieger. -

VILLA-LOBOS Bachianas Brasileiras (Complete) Rosana Lamosa, Soprano • José Feghali, Piano Nashville Symphony Orchestra Kenneth Schermerhorn

557460-62bk USA 24/9/05 8:20 am Page 12 KENNETH SCHERMERHORN VILLA-LOBOS Bachianas Brasileiras (Complete) Rosana Lamosa, Soprano • José Feghali, Piano Nashville Symphony Orchestra Kenneth Schermerhorn 8.557460-62 12 557460-62bk USA 24/9/05 8:20 am Page 2 Heitor Villa-Lobos (1887-1959) 6 Dansa Dansa Bachianas brasileiras (Manoel Bandeira: 1886-1968) Irerê, meu passarinho do Sertão do Cariri, Irere, my little bird from the backwoods of Cariri, CD1 73:10 Irerê, meu companheiro, Irere, my companion, Cadê vióla? Cadê meu bem? Cadê Maria? Where is the guitar? Where is my beloved? Where is Maria? No. 1 for ‘an orchestra of cellos’ (1930) * 19:50 Ai triste sorte a do violeiro cantadô! Oh, the sad lot of the guitarist singing! 1 Introdução – Embolada 6:57 Ah! Sem a vióla em que cantava o seu amô, Ah, without the guitar with which its master was singing, 2 Prelúdio – Modinha 8:37 Ah! Seu assobio é tua flauta de Irerê: Ah, his whistling is your flute, Irere: 3 Fuga – Conversa (Conversation) 4:16 Que tua flauta do sertão quando assobia, When your flute of the backwoods whistles, Ah! A gente sofre sem querê! Ah, people suffer without wanting to! No. 2 for chamber orchestra (1930) 22:16 Ah! Teu canto chega lá do fundo do sertão, Ah, your song comes there from the deep backwoods, 4 Prelúdio – O Canto do capadócio (Scamp’s Song) 7:10 Ah! Como uma brisa amolecendo o coração, Ah, like a breeze softening the heart, 5 Aria – O Canto da nossa terra (Song of Our Land) 5:50 Ah! Ah! Ah! Ah! 6 Dança – Lembrança do Sertão (Remembrance of the Bush) 4:54 Irerê, solta o teu canto! Irere, set free your song! 7 Toccata – O trenzinho do Caipira (The Peasant’s Little Train) 4:22 Canta mais! Canta mais! Sing more! Sing more! Pra alembrá o Cariri! To recall the Cariri! No. -

Eastman Notes July 2006

“Serving a Great and Noble Art” Eastman Historian Vincent Lenti surveys the Howard Hanson years E-Musicians Unite! Entrepreneurship, ESM style Tony Arnold Hitting high notes in new music Summer 2009 FOr ALUMNI, PARENTS, AND FrIeNDS OF THe eASTmAN SCHOOL OF MUSIC FROM THE DEAN The Teaching Artist I suppose that in the broadest sense, art may be one of our greatest teachers. Be it a Bach Goldberg Variation, the brilliant economy of Britten’s or- chestration in Turn of the Screw, the music in the mad ruminations of King Lear, or the visual music of Miro, it is the stirring nature of such intense, insightful observation that moves us. Interestingly, these artistic epiphanies bear a remarkable resemblance to what happens during great teaching. And I believe that some of the many achieve- ments of Eastman alumni, faculty and students can be traced to great Eastman “teaching moments.” Like great art, great teaching is not merely the efficient transmission of knowl- NOTES edge or information, but rather a process by which music Volume 27, Number 2 or information gets illuminated by an especially insight- Summer 2009 ful light, thus firing our curiosity and imagination. Great teachers, like great artists, possess that “special light.” Editor It’s hard to define what constitutes good teaching. In David Raymond the academic world, we try to quantify it, for purposes Contributing writers of measurement, so we design teaching evaluations that Lisa Jennings Douglas Lowry hopefully measure the quality of the experience. Yet Helene Snihur when each of us is asked to describe our great teachers, Contributing photographers we end up being confounded, indeed fascinated, by the Richard Baker dominant intangibles; like music or other art, the price- Steve Boerner less stirring aspects we just can’t “explain.” Kurt Brownell Great music inspires us differently, depending on tem- Gary Geer Douglas Lowry Gelfand-Piper Photography perament, musical and intellectual inclinations, moods, Kate Melton backgrounds, circumstances and upbringings.