2734 January 2012 NEWSLETTER the JOURNAL of the LONDON NUMISMATIC CLUB HONORARY EDITOR Peter A

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Romans in Worcester a Town and Its Hinterland Education Pack

The Romans in Worcester A Town and its Hinterland Education Pack Education Pack Welcome The Romans in Worcester resource is intended to align with the national curriculum in England, with the focus on Worcester and its hinterland bringing the wider understanding of Roman Britain closer to home. The resource book provides information for teachers of Key Stage 2 learners, along with accompanying PowerPoint presentations, suggested activities and other resources. There is an accompanying loan box incorporating replica items as well as archaeological finds from the Mab’s Orchard excavation at Warndon, Worcester. The book is laid out with information for teachers shown alongside the relevant PowerPoint slides, to help you explore a variety of themes with your learners. At the start of each chapter and before each activity, we provide a listing of relevant points in the Key Stage 2 programme of study. The understanding of historical concepts, such as continuity and change, cause and consequence, similarity and difference, is a key aim within the national curriculum for history, while the Roman Empire and its impact on Britain (including ‘Romanisation’ of Britain: sites such as Caerwent and the impact of technology, culture and beliefs, including early Christianity) is a required part of the Key Stage 2 curriculum. Therefore we have highlighted key changes and new introductions that took place in the Roman period by marking the text in bold. We hope that you will find this a useful and inspiring resource for bringing archaeology and the Romans into your classroom. There were glaciers in the Scottish Timeline of Archaeological Highlands until around 10,000 years ago Periods in England Last Ice Age Palaeolithic 500,000 BC Hunting and gathering se of flint tools Spear point People being to move from hunting 10,000 BC esolithic and gathering towards food production i.e. -

17Recensioni 337..386

RIVISTA ITALIANA DI NVMISMATICA E SCIENZE AFFINI FONDATA DA SOLONE AMBROSOLI NEL 1888 EDITA DALLA SOCIETA` NUMISMATICA ITALIANA ONLUS - MILANO VOL. CXIV 2013 Estratto INDICE MATERIALI C. PERASSI, Numismatica insulare. Le monete delle zecche di Melita e di Gaulos della Collezione Nazionale Maltese ......... » 15 G. FUSCONI, Gli antiquiores romani della collezione Palagi conser- vati al Museo Civico Archeologico di Bologna ........... » 53 A. SACCOCCI, A. CONVENTI, Un denaro inedito di Verona a nome di Adalberto re d’Italia (950-961) ..................... » 81 S. SANTANGELO, Due ripostigli di tarı`arabo-normanni dalla provin- cia di Ragusa: Spaccaforno e Modica 1907 ............ » 97 SAGGI CRITICI P. VISONA`, Out of Africa. The Movement of Coins of Massinissa and his Successors across the Mediterranean. Part one ........ » 119 M. CARDONE, Studio sulla frequenza delle emissioni provinciali au- gustee della penisola iberica sulle aste pubbliche on line ... » 151 S. MARSURA, Monnayage et images fe´minines dans l’Aquitaine ro- maine ......................................... » 167 L. DEL BASSO, L. ZAMBONI, Problematiche inerenti l’introduzione del tipo della Fecunditas nella monetazione romana: il caso di Faustina Maggiore e il significato della maternita`nella di- nastia antonina .................................. » 211 E. BULTRINI, Monetazione ed araldica nell’ostentazione dell’aristo- crazia romana medievale (secoli XIII-XIV) ............. » 221 10 Indice L. GIANAZZA, R. GENOVESI, Falsari a Capiago nel 1493: un errore giudiziario contro alchimisti tedeschi? ................. » 239 S. PERFETTO, L’ officio di mastro di banca e un ‘‘discorso intorno alli carichi et oblichi che teneno li regii officiali in la regia zecca dela moneta di questa citta` di Napoli’’ (10 di iennaro 1584) ......................................... » 255 A. BERNARDELLI, Gettare monete nella Fontana di Trevi. -

World Heritage Watch: Report 2018. WHW

W H W World Heritage Watch Report 2018 World Heritage Watch Report 2018 Report Watch Heritage World World Heritage Watch Heritage World World Heritage Watch World Heritage Watch Report 2018 Berlin 2018 2 Bibliographical Information World Heritage Watch: World Heritage Watch Report 2018. Berlin 2018 184 pages, with 217 photos and 53 graphics and maps Published by World Heritage Watch e.V. Berlin 2018 ISBN 978-3-00-059753-4 NE: World Heritage Watch 1. World Heritage 2. Civil Society 3. UNESCO 4. Participation 5. Natural Heritage 6. Cultural Heritage 7. Historic Cities 8. Sites 9. Monuments 10. Cultural Landscapes 11. Indigenous Peoples 12. Participation W H W © World Heritage Watch e.V. 2018 This work with all its parts is protected by copyright. Any use beyond the strict limits of the applicable copyright law without the consent of the publisher is inadmissable and punishable. This refers especially to reproduction of figures and/or text in print or xerography, translations, microforms and the data storage and processing in electronical systems. The designations employed and the presentation of the material in this publication do not imply the expression of any opinions whatsoever on the part of the publishers concerning the legal status of any country or territory or of its authorities, or concerning the frontiers of any country or territory. The authors are responsible for the choice and the presentation of the facts contained in this book and for the opinions expressed therein, which are not necessarily those of the editors, and do not commit them. No part of this publication may be reproduced in any form without written permission from the publishers except for the quotation of brief passages for the purposes of review. -

WRAP Theses Earle 1994.Pdf

A Thesis Submitted for the Degree of PhD at the University of Warwick Permanent WRAP URL: http://wrap.warwick.ac.uk/104927 Copyright and reuse: This thesis is made available online and is protected by original copyright. Please scroll down to view the document itself. Please refer to the repository record for this item for information to help you to cite it. Our policy information is available from the repository home page. For more information, please contact the WRAP Team at: [email protected] warwick.ac.uk/lib-publications THE BRITISH LIBRARY BRITISH THESIS SERVICE THE RESTORATION AND FALL OF ROYAL TITLE GOVERNMENT IN NEW GRANADA 1815-1820 AUTHOR Rebecca A. EARLE DEGREE Ph.D AWARDING Warwick University BODY DATE 1994 THESIS DX184477 NUMBER THIS THESIS HAS BEEN MICROFILMED EXACTLY AS RECEIVED The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the original thesis submitted for microfilming. Every effort has been made to ensure the highest quality of reproduction. Some pages may have indistinct print, especially if the original papers were poorly produced or if awarding body sent an inferior copy. If pages are missing, please contact the awarding body which granted the degree. Previously copyrighted materials (journals articles, published texts etc.) are not filmed. This copy of the thesis has been supplied on condition that anyone who consults it is understood to recognise that it's copyright rests with its author and that no information derived from it may be published without the author's prior written consent. Reproduction of this thesis, other than as permitted under the United Kingdom Copyright Designs and Patents Act 1988, or under specific agreement with the copyright holder, is prohibited. -

View the Enlightenment As a Catalyst for Beneficial Change in the Region

UNA REVOLUCION, NI MAS NI MENOS: THE ROLE OF THE ENLIGHTENMENT IN THE SUPREME JUNTAS IN QUITO, 1765-1822 Thesis Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for The Degree Master of Arts in the Graduate School of The Ohio State University By Beau James Brammer, B.A. Graduate Program in History The Ohio State University 2010 Master’s Examination Committee: Kenneth Andrien, Adviser Stephanie Smith Alan Gallay Copyright by Beau James Brammer 2010 Abstract This thesis examines the role the European Enlightenment played in the political sphere during the late colonial era in the Audiencia of Quito. Until the eighteenth century, Creole elites controlled the local economic and governmental sectors. With the ascension of the Bourbon dynasty in 1700, however, these elites of Iberian descent began to lose their power as new European ideas, emerging from the Enlightenment, led to a process of consolidating and centralizing power into the hands of Peninsular Spanish officials. Known as the Bourbon Reforms, these measures led to Creole disillusionment, as they began losing power at the local level. Beginning in the 1770s and 1780s, however, Enlightenment ideas of “nationalism” and “rationality” arrived in the Andean capital, making their way to the disgruntled Creoles. As the situation deteriorated, elites began to incorporate these new concepts into their rhetoric, presenting a possible response to the Reforms. When Napoleon invaded Spain in 1808, the Creoles expelled the Spanish government in Quito, creating an autonomous movement, the Junta of 1809, using these Enlightenment principles as their justification. I argue, however, that while these ‘modern’ principles gave the Creoles an outlet for their grievances, it is their inability to find a common ground on how their government should interpret these new ideas which ultimately lead to the Junta’s failure. -

The Portable Antiquities Scheme Annual Report 2011

The Portable Antiquities Scheme Annual Report 2011 Edited by Michael Lewis Published by the Department of Portable Antiquities and Treasure, British Museum 1 2 Foreword We are pleased to introduce this report on the work of the Portable Antiquities Scheme (PAS) and Treasure Act 1996, which also highlights some fascinating and important finds reported in 2011. We are especially grateful to Treasure Hunting who once again agreed to publish this report free within their magazine. The PAS and Treasure Act continue to be a great success, Ed Vaizey highlighted by the fact that ITV have made a primetime Minister for Culture, television series – Britain’s Secret Treasures – about the top 50 finds Communications & found by the public. It is thanks to the efforts of the finders Creative Industries and to the work of the PAS, particularly its network of Finds Liaison Officers, that 97,509 PAS and 970 Treasure finds were reported in 2011. This recording work was supported by interns, volunteers and finders who record their own discoveries, and we are particularly grateful to the Headley Trust and the Institute for Archaeologists/Heritage Lottery Fund who funded interns in the period of this report. We are therefore delighted that the Headley Trust has agreed to extend its funding for interns for a further two years, 2012/13 and 2013/14. We are also grateful to Neil MacGregor the generosity of an American philanthropist who has funded the Director of the post of assistant to the Finds Adviser for Iron Age and Roman British Museum coins, for two years. Archaeological finds discovered by the public are helping to rewrite the archaeology and history of our past, and therefore it is excellent news that the Leverhulme Trust has agreed to fund a £150k project, ‘The PAS database as a tool for archaeological research’, to examine in detail the factors that underlie this large and rapidly growing dataset. -

Presidential Address 2014 Coin Hoards and Hoarding in Britain

PRESIDENTIAL ADDRESS 2014 COIN HOARDS AND HOARDING IN BRITAIN (3): RADIATE HOARDS ROGER BLAND Introduction IN my first presidential address I gave an overview of hoarding in Britain from the Bronze Age through to recent times,1 while last year I spoke about hoards from the end of Roman Britain.2 This arises from a research project (‘Crisis or continuity? Hoards and hoarding in Iron Age and Roman Britain’) funded by the Arts and Humanities Research Council and based at the British Museum and the University of Leicester. The project now includes the whole of the Iron Age and Roman periods from around 120 BC to the early fifth century. For the Iron Age we have relied on de Jersey’s corpus of 340 Iron Age coin hoards and we are grateful to him for giving us access to his data in advance of publica- tion.3 For the Roman period, our starting point has been Anne Robertson’s Inventory of Romano-British Coin Hoards (RBCH),4 which includes details of 2,007 hoards, including dis- coveries made down to about 1990. To that Eleanor Ghey has added new discoveries and also trawled other data sources such as Guest and Wells’s corpus of Roman coin finds from Wales,5 David Shotter’s catalogues of Roman coin finds from the North West,6 Penhallurick’s corpus of Cornish coin finds,7 Historic Environment Records and the National Monuments Record. She has added a further 1,045 Roman hoards, taking the total to 3,052, but this is not the final total. -

Chavez Presents Boli

xviii FURTHER READING STUDIES ON BOLIVAR AND INDEPENDENCE Brown, Matthew, Adventuring Through Spanish Colonies: Sifnon BoUvar, Foreign Mercenaries and the Birth of New Nations (Liverpool: Liverpool University Press, 2006) Conway, Christopher Brian, The Cult of BoUvar in Latin Aincricati Literature (Gainesville: University of Florida Press, 2003) Davies, Catherine, Claire Brewster and Hillary Owen, South Anicricati Independence: Gender, Politics, Text (Liverpool: Liverpool University Press, 2006) Earle, Rebecca, Spain and the Independence of Colombia (Exeter: University of Exeter Press, 2000) Lynch, John, Latin American Revolutions 1808-1826 (Norman: University of Oklahoma Press, 1994) Murray, Pamela, For Glory and BoUvar: The Remarkable Life of Manuela Saenz (Austin: University of Texas Press, 2008) f CHRONOLOGY 1783 24 July: Simon Jose Antonio de la Santisima Trinidad Bolivar y Palacios bom in Caracas. 1799-1802 Bolivar visits and lives in New Spain (Mexico), Spain and France. 1802 26 May: Bolivar marries Maria Teresa Rodriguez del Toro in Madrid. 1803 22 January: Maria Teresa Rodriguez del Toro dies in Caracas. 1803-1807 Bolivar travels to Spain, France, Italy and the USA. 1810 19 April: Caracas rebels against colonial mle and deposes Captain-General. New junta governs, autonomously, in the name of deposed King Femando VII. Bolivar travels to London as part of Venezuelan mission seeking recognition of its independence (returns to Venezuela in December). r k X X C H R O N O L O G Y 1811 5 July: Elected Venezuelan Congress declares independence. Beginning of First Republic. 1812 26 March: Earthquake in Caracas. 6 July: Bolivar abandons Puerto Cabello. 31 July: Bolivar complicit in arrest of Francisco de Miranda. -

Tyranny Or Victory! Simón Bolívar's South American Revolt

ODUMUNC 2018 Issue Brief Tyranny or Victory! Simón Bolívar’s South American Revolt by Jackson Harris Old Dominion University Model United Nations Society of the committee, as well as research, all intricacies involved in the committee will be discussed in this outline. The following sections of this issue brief will contain a topical overview of the relevant history of Gran Colombia, Simón Bolívar, and Spanish-American colonial relations, as well as an explanation of the characters that delegates will be playing. This guide is not meant to provide a complete understanding of the history leading up to the committee, rather to provide a platform that will be supplemented by personal research. While there are a number of available online sources the Crisis Director has provided the information for a group of helpful books to use at the delegate’s discretion. The legacy of Simón Bolívar, the George Washington of South America, is anything but historical. His life stands at the center of contemporary South America.1 Any doubt about his relevance was eliminated on 16 July 2010 when Venezuelan President Hugo Chávez presided at the exhumation of Bolívar’s remains.2 Pieces of the skeleton were El Libertador en traje de campaña, by Arturo Michelena 1985, Galería de Arte Nacional 1 Gerhard Straussmann Masur, ‘Simón Bolívar: Venezuelan soldier and statesman’, Encyclopædia Britannica, n.d., https://www.britannica.com/biography/Simo n-Bolivar ; and Christopher Minster, FORWARD ‘Biography of Simon Bolivar: Liberator of ¡Bienvenidos delegados! Welcome to the South America’, ThoughtCo., 8 September Tyranny or Victory! Simón Bolívar’s 2017, South American Revolt crisis committee! https://www.thoughtco.com/biography-of- In order to allow delegates to familiarize simon-bolivar-2136407 2 Thor Halvorssen, ‘Behind exhumation of themselves with the rules and procedures Simon Bolivar is Hugo Chavez's warped Tyranny or Victory! Simón Bolívar’s South American Revolt removed for testing. -

The Frome Hoard How a Massive Find Changes Everything

281 SAM MOORHEAD National Finds Adviser for Iron Age and Roman coins, Portable Antiquities and Treasure, British Museum THE FROME HOARD HOW A MASSIVE FIND CHANGES EVERYTHING Abstract The Frome Hoard of 52,503 coins, discovered in 2010, is the second largest Roman coin hoard found in Britain. Not only is it of great numismatic significance, with over 850 pieces of Carausius (AD 286-93), but also it has had an enormous impact on broader archaeological and museological practices. The hoard was discovered by a metal detectorist, Dave Crisp, but he left the pot in the ground for professional excavation. This provided invaluable context for the hoard and enabled numismatists to determine that the hoard was buried in a single event. The sudden arrival of the coins at the British Museum was a catalyst for the Roman Coin and Metals Conservation sections at the British Museum to develop a new way of processing the 80 or so hoards which arrive annually. The apparent ritual significance of the hoard led to much academic and popular debate, resulting in a major Arts and Humanities Research Council research project between Leicester University and the British Museum. The worldwide publicity concerning the hoard enabled a major fund-raising campaign which secured the coins for the Museum of Somerset in Taunton. The high profile of the hoard also resulted in a British Museum video-conferencing activity for school children. Finally, the good practice of Dave Crisp, in calling for professional assistance, has resulted in numerous detectorists leaving hoards in the ground for archaeologists to excavate. -

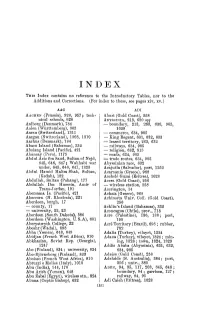

For Index to These, See Pages Xiv, Xv.)

INDEX THis Index contains no reference to the Introductory Tables, nor to the Additions and Corrections. (For index to these, see pages xiv, xv.) AAC ADI AAcHEN (Prussia), 926, 957; tech- Aburi (Gold Coast), 258 nical schools, 928 ABYSSINIA, 213, 630 sqq Aalborg (Denmark), 784 - boundary, 213, 263, 630, 905, Aalen (Wiirttemberg), 965 1029 Aarau (Switzerland), 1311 - commerce, 634, 905 Aargau (Switzerland), 1308, 1310 - King Regent, 631, 632, 633 Aarhus (Denmark), 784 - leased territory, 263, 632 Abaco Island (Bahamas), 332 - railways, 634, 905 Abaiaug !Rland (Pacific), 421 - religion, 632, 815 Abancay (Peru), 1175 - roads, 634, 905 Abdul Aziz ibn Saud, Sultan of N ejd, -trade routes, 634, 905 645, 646, 647; Wahhabi war Abyssinian race, 632 under, 645, 646, 647, 1323 Acajutla (Salvador), port, 1252 Abdul Hamid Halim Shah, Sultan, Acarnania (Greece), 968 (Kedah), 182 Acchele Guzai (Eritrea), 1028 Abdullah, Sultan (Pahang), 177 Accra (Gold Coast), 256 Abdullah Ibn Hussein, Amir of - wireless station, 258 Trans-J orrlan, 191 Accrington, 14 Abemama Is. (Pacific), 421 Acha!a (Greece), 968 Abercorn (N. Rhodesia), 221 Achirnota Univ. Col!. (Gold Coast), Aberdeen, burgh, 17 256 - county, 17 Acklin's Island (Bahamas), 332 -university, 22, 23 Aconcagua (Chile), prov., 718 Aberdeen (South Dakota), 586 Acre (Palestine), 186, 188; port, Aberdeen (Washington, U.S.A), 601 190 Aberystwyth College, 22 Acre Territory (Brazil), 698 ; rubber, Abeshr (Wadai), 898 702 Abba (Yemen), 648, 649 Adalia (Turkey), vilayet, 1324 Abidjan (French West Africa), 910 Adana (Turkey), vilayet, 1324; min Abkhasian, Soviet Rep. (Georgia), ing, 1328; town, 1324, 1329 1247 Addis Ababa (Abyssinia), 631, 632, Abo (Finland), 834; university, 834 634, 905 Abo-Bjorneborg (Finland), 833 Adeiso (Gold Coast), 258 Aboisso (French West Africa), 910 Adelaide (S. -

A Literary and Historical Atlas of America

EVERYMAN .1 WILL? GO V-* ~~^--m^r >* IN THY MOST NEED THEE & BE THY GUIDE O GO BY THY SIDE ^OVyfcxvJL Presented to the LIBRARY of the UNIVERSITY OF TORONTO by Sybille Pantazzi EVERYMAN'S LIBRARY EDITED BY ERNEST RHYS REFERENCE A L I TE R A R Y AND HISTORICAL ATLAS OF NORTH & SOUTH AMERICA THE PUBLISHERS OF LlBT^ATty WILL BE PLEASED TO SEND FREELY TO ALL APPLICANTS A LIST OF THE PUBLISHED AND PROJECTED VOLUMES TO BE COMPRISED UNDER THE FOLLOWING THIRTEEN HEADINGS: TRAVEL ^ SCIENCE ^ FICTION THEOLOGY & PHILOSOPHY HISTORY ^ CLASSICAL FOR YOUNG PEOPLE ESSAYS $ ORATORY POETRY & DRAMA BIOGRAPHY REFERENCE ROMANCE IN FOUR STYLES OF BINDING; CLOTH, FLAT BACK, COLOURED TOP; LEATHER, ROUND CORNERS, GILT TOP; LIBRARY BINDING IN CLOTH, & QUARTER PIGSKIN LONDON: J. M. DENT & SONS, LTD. NEW YORK: E. P. DUTTON & CO. I ALITERARYS HISTORICAL ATLAS OF AMERICA? J G.BARTHOLOMEW LL.D LONLON:PUBL4SHED hyJMDENTS-SONS^ ANP IN NEW YORK BYE-P DUTTONSCO / INTRODUCTION WHEN General Hamilton spoke in the Federalist over a " century ago of an empire, in many respects the most inter- esting in the world," meaning the United States of America, he did not, he could not, foresee the vast growth of his country and its northern and southern neighbours which this book portrays. The volume is the third in a series of small atlases, meant to cover in turn the whole globe, and to do it in a way to knit up geographical and historical knowledge with the facts of commerce and the literary record of each land or region. One chief purpose of these maps is to trace clearly " the development of the United States, beginning with the " most remarquable parts of the New England of the Pilgrim Fathers, described by Captain John Smith in 1614, and not forgetting the territories of the old American-Indian nations.