Good Night and Good-Bye: Temporal and Spatial Rhythms in Piecing Together Emma Goldman’S Auto/Biographical Fragments

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

"Red Emma"? Emma Goldman, from Alien Rebel to American Icon Oz

Whatever Happened to "Red Emma"? Emma Goldman, from Alien Rebel to American Icon Oz Frankel The Journal of American History, Vol. 83, No. 3. (Dec., 1996), pp. 903-942. Stable URL: http://links.jstor.org/sici?sici=0021-8723%28199612%2983%3A3%3C903%3AWHT%22EE%3E2.0.CO%3B2-B The Journal of American History is currently published by Organization of American Historians. Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of JSTOR's Terms and Conditions of Use, available at http://www.jstor.org/about/terms.html. JSTOR's Terms and Conditions of Use provides, in part, that unless you have obtained prior permission, you may not download an entire issue of a journal or multiple copies of articles, and you may use content in the JSTOR archive only for your personal, non-commercial use. Please contact the publisher regarding any further use of this work. Publisher contact information may be obtained at http://www.jstor.org/journals/oah.html. Each copy of any part of a JSTOR transmission must contain the same copyright notice that appears on the screen or printed page of such transmission. The JSTOR Archive is a trusted digital repository providing for long-term preservation and access to leading academic journals and scholarly literature from around the world. The Archive is supported by libraries, scholarly societies, publishers, and foundations. It is an initiative of JSTOR, a not-for-profit organization with a mission to help the scholarly community take advantage of advances in technology. For more information regarding JSTOR, please contact [email protected]. -

Anarchy! an Anthology of Emma Goldman's Mother Earth

U.S. $22.95 Political Science anarchy ! Anarchy! An Anthology of Emma Goldman’s MOTHER EARTH (1906–1918) is the first An A n t hol o g y collection of work drawn from the pages of the foremost anarchist journal published in America—provocative writings by Goldman, Margaret Sanger, Peter Kropotkin, Alexander Berkman, and dozens of other radical thinkers of the early twentieth cen- tury. For this expanded edition, editor Peter Glassgold contributes a new preface that offers historical grounding to many of today’s political movements, from liber- tarianism on the right to Occupy! actions on the left, as well as adding a substantial section, “The Trial and Conviction of Emma Goldman and Alexander Berkman,” which includes a transcription of their eloquent and moving self-defense prior to their imprisonment and deportation on trumped-up charges of wartime espionage. of E m m A g ol dm A n’s Mot h er ea rt h “An indispensable book . a judicious, lively, and enlightening work.” —Paul Avrich, author of Anarchist Voices “Peter Glassgold has done a great service to the activist spirit by returning to print Mother Earth’s often stirring, always illuminating essays.” —Alix Kates Shulman, author of Memoirs of an Ex-Prom Queen “It is wonderful to have this collection of pieces from the days when anarchism was an ism— and so heady a brew that the government had to resort to illegal repression to squelch it. What’s more, it is still a heady brew.” —Kirkpatrick Sale, author of The Dwellers in the Land “Glassgold opens with an excellent brief history of the publication. -

The Life and Times of Emma Goldman: a Curriculum for Middle and High School Students

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 356 998 SO 023 057 AUTHOR Falk, Candace; And Others TITLE The Life and Times of Emma Goldman: A Curriculum for Middle and High School Students. Primary Historical Documents on: Immigration, Freedom of Expression, Women's Rights, Anti-Militarism, Art and Literature of Social Change. INSTITUTION California Univ., Berkeley. Emma Goldman Papers Project.; Los Angeles Educational Partnership, CA.; New Directions Curriculum Developers, Berkeley, CA. REPORT NO ISBN-0-9635443-0-6 PUB DATE 92 NOTE 139p.; Materials reproduced from other sources will not reproduce well. AVAILABLE FROMEmma Goldman Papers Project, University of California, 2372 Ellsworth Street, Berkeley, CA 94720 ($13, plus $3 shipping). PCB TYPE Guides Classroom Use Teaching Guides (For Teacher) (052) EDRS PRICE MF01/PC06 Plus Postage. DESCRIPTORS *Females; Feminism; Freedom of Speech; Higher Education; High Schools; Hig ,School Students; *Humanities Instruction; Intermediate Grades; Junior High Schools; Labor; Middle Schools; Primary Sources; *Social Studies; *United States History; Units of Study IDENTIFIERS *Goldman (Emma); Middle School Students ABSTRACT The documents in this curriculum unit are drawn from the massive archive collected by the Emma Goldman Papers Project at the University of California (Berkeley). They are linked to the standard social studies and humanities curriculum themes of art and literature, First Amendment rights, labor, progressive politics, and Red Scare, the rise of industrialization, immigration, women's rights, World War I, and -

Quiet Rumours: an Anarcha-Feminist Reader Ebook, Epub

QUIET RUMOURS: AN ANARCHA-FEMINIST READER PDF, EPUB, EBOOK Emma Goldman,Voltairine De Cleyre,Roxanne Dunbar-Ortiz,Jo Freeman | 136 pages | 11 Dec 2012 | AK Press | 9781849351034 | English | Edinburgh, United Kingdom Quiet Rumours: An Anarcha-Feminist Reader PDF Book Refresh and try again. Emma Goldman's "A Woman Without a Country," though a great text, mentioned nothing of feminism, let alone anarchist feminism. View all 9 comments. Quiet Rumors provides anarcha-feminists and other readers with a solid archive of political inquiry stretching across two centuries and engaging the debates, disappointments, and dreams expressed within critical moments in multiple liberation movements. Nor is a fringe mention of intersectionality enough to make our feminism intersectional. Why were they picked for this anthology? Most these essays didn't have any context introducing them: what year were they written? Aug 04, Ariel rated it really liked it Recommended to Ariel by: Lambert. Known as a rebel, a labor agitator, an ardent proponent of birth control and free speech, a feminist, a lecturer and a writer, Goldman is the author of countless essays, as well as several collections of writings published posthumously, and her 2-volume autobiography, Living My Life. Some of the classical stuff was kinda boring. The articles from the s, which ought to be the most interesting since they are from new left feminists dis This is mainly of historical interest, and in the meantime probably all of the documents collected here are freely available online. Technopranks: Carving out a message in electronic space. A: Its policy, it aims, its principles. -

Sasha and Emma the ANARCHIST ODYSSEY OF

Sasha and Emma THE ANARCHIST ODYSSEY OF ALEXANDER BERKMAN AND EMMA GOLDMAN PAUL AVRICH KAREN AVRICH SASHA AND EMMA SASHA and EMMA The Anarchist Odyssey of Alexander Berkman and Emma Goldman Paul Avrich and Karen Avrich Th e Belknap Press of Harvard University Press Cambridge, Massachusetts • London, En gland 2012 Copyright © 2012 by Karen Avrich. All rights reserved Printed in the United States of America Library of Congress Cataloging- in- Publication Data Avrich, Paul. Sasha and Emma : the anarchist odyssey of Alexander Berkman and Emma Goldman / Paul Avrich and Karen Avrich. p . c m . Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 978- 0- 674- 06598- 7 (hbk. : alk. paper) 1. Berkman, Alexander, 1870– 1936. 2. Goldman, Emma, 1869– 1940. 3. Anarchists— United States— Biography. 4 . A n a r c h i s m — U n i t e d S t a t e s — H i s t o r y . I . A v r i c h , K a r e n . II. Title. HX843.5.A97 2012 335'.83092273—dc23 [B] 2012008659 For those who told their stories to my father For Mark Halperin, who listened to mine Contents preface ix Prologue 1 i impelling forces 1 Mother Rus sia 7 2 Pioneers of Liberty 20 3 Th e Trio 30 4 Autonomists 43 5 Homestead 51 6 Attentat 61 7 Judgment 80 8 Buried Alive 98 9 Blackwell’s and Brady 111 10 Th e Tunnel 124 11 Red Emma 135 12 Th e Assassination of McKinley 152 13 E. G. Smith 167 ii palaces of the rich 14 Resurrection 181 15 Th e Wine of Sunshine and Liberty 195 16 Th e Inside Story of Some Explosions 214 17 Trouble in Paradise 237 18 Th e Blast 252 19 Th e Great War 267 20 Big Fish 275 iii -

CIVIL RIGHTS and SOCIAL JUSTICE Abolitionism: Activism to Abolish

CIVIL RIGHTS and SOCIAL JUSTICE Abolitionism: activism to abolish slavery (Madison Young Johnson Scrapbook, Chicago History Museum; Zebina Eastman Papers, Chicago History Museum) African Americans at the World's Columbian Exposition/World’s Fair of 1893 (James W. Ellsworth Papers, Chicago Public Library; World’s Columbian Exposition Photographs, Loyola University Chicago) American Indian Movement in Chicago Anti-Lynching: activism to end lynching (Ida B. Wells Papers, University of Chicago; Arthur W. Mitchell Papers, Chicago History Museum) Asian-American Hunger Strike at Northwestern U Ben Reitman: physician, activist, and socialist; founder of Hobo College (Ben Reitman Visual Materials, Chicago History Museum; Dill Pickle Club Records, Newberry Library) Black Codes: denied ante-bellum African-Americans living in Illinois full citizenship rights (Chicago History Museum; Platt R. Spencer Papers, Newberry Library) Cairo Civil Rights March: activism in southern Illinois for civil rights (Beatrice Stegeman Collection on Civil Rights in Southern Illinois, Southern Illinois University; Charles A. Hayes Papers, Chicago Public Library) Carlos Montezuma: Indian rights activist and physician (Carlos Montezuma Papers, Newberry Library) Charlemae Hill Rollins: advocate for multicultural children’s literature based at the George Cleveland Branch Library with Vivian Harsh (George Cleveland Hall Branch Archives, Chicago Public Library) Chicago Commission on Race Relations / The Negro in Chicago: investigative committee commissioned after the race riots -

Anarchy and Anti-Intellectualism: Reason, Foundationalism, and the Anarchist Tradition Joaquin A

Florida International University FIU Digital Commons FIU Electronic Theses and Dissertations University Graduate School 6-23-2016 Anarchy and Anti-Intellectualism: Reason, Foundationalism, and the Anarchist Tradition Joaquin A. Pedroso [email protected] DOI: 10.25148/etd.FIDC000744 Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.fiu.edu/etd Part of the Philosophy Commons, and the Political Theory Commons Recommended Citation Pedroso, Joaquin A., "Anarchy and Anti-Intellectualism: Reason, Foundationalism, and the Anarchist Tradition" (2016). FIU Electronic Theses and Dissertations. 2578. https://digitalcommons.fiu.edu/etd/2578 This work is brought to you for free and open access by the University Graduate School at FIU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in FIU Electronic Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of FIU Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. FLORIDA INTERNATIONAL UNIVERSITY Miami, Florida ANARCHY AND ANTI-INTELLECTUALISM: REASON, FOUNDATIONALISM, AND THE ANARCHIST TRADITION A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY in POLITICAL SCIENCE by Joaquin A. Pedroso 2016 To: Dean John F. Stack, Jr. Steven J. Green School of International and Public Affairs This dissertation, written by Joaquin A. Pedroso, and entitled Anarchy and Anti- Intellectualism: Reason, Foundationalism, and the Anarchist Tradition, having been approved in respect to style and intellectual content, is referred to you for judgment. We have read this dissertation and recommend that it be approved. _______________________________________ Paul Warren _______________________________________ Bruce Hauptli _______________________________________ Ronald Cox _______________________________________ Harry Gould _______________________________________ Clement Fatovic, Major Professor Date of Defense: June 23, 2016 The dissertation of Joaquin A. -

Emma Goldman Reading Walt Whitman: Aesthetics, Agitation, and the Anarchist Ideal

(PPD*ROGPDQ5HDGLQJ:DOW:KLWPDQ$HVWKHWLFV $JLWDWLRQDQGWKH$QDUFKLVW,GHDO 7LPRWK\5REELQV Texas Studies in Literature and Language, Volume 57, Number 1, Spring 2015, pp. 80-105 (Article) 3XEOLVKHGE\8QLYHUVLW\RI7H[DV3UHVV DOI: 10.1353/tsl.2015.0003 For additional information about this article http://muse.jhu.edu/journals/tsl/summary/v057/57.1.robbins.html Access provided by The University of Iowa Libraries (8 Mar 2015 05:32 GMT) Emma Goldman Reading Walt Whitman: Aesthetics, Agitation, and the Anarchist Ideal Timothy Robbins I want freedom, the right to self-expression, everybody’s right to beautiful, radiant things. Anarchism meant that to me, and I would live it in spite of the whole world—prisons, persecution, everything. Yes, even in spite of the condemnation of my own closest comrades I would live my beautiful ideal. —Emma Goldman, Living My Life Do you suppose you will find in me your ideal? —Walt Whitman, Leaves of Grass In June of 1919, the Walt Whitman Fellowship International held a celebra- tion commemorating the centennial of the birth of America’s “good grey poet” weeks before his motherland signed the treaty that would end the first “great war” to connect the modern world. Yet with legislative peace on the global horizon, turmoil erupted at a local Whitman procession. The New York Times reported on the antiwar demonstrations led by “a series of radical speeches based upon [Whitman’s] writings” (“Viereck Breaks Up” 17). George Smith, a local school examiner and the evening’s host, came under fire from the board of education for virtually sanctioning the pro- tests by reading aloud a telegram sent by Emma Goldman from a federal prison in Jefferson City, Missouri (“Must Explain” 2). -

View the Program & Bibliography

MONDAY Praxis Poems: JUL 01 Radical Genealogies of Yiddish Poetry ANNA ELENA TORRES | Delivered in English This talk will survey the radical traditions of Yiddish poetry, focusing on anarchist poetics and the press. Beginning with the Labor poets, also known as the Svetshop or Proletarian poets, the lecture discusses the formative role of the anarchist press in the development of immigrant social worlds. Between 1890 and World War I, Yiddish anarchists published more than twenty newspapers in the U.S.; these papers generally grew out of mutual aid societies that aspired to cultivate new forms of social life. Fraye Arbeter Shtime (Free Voice of Labor)—which was founded in 1890 and ran until 1977, making it the longest-running anarchist newspaper in any language—launched the careers of many prominent poets, including Dovid Edelshtat, Mani Leyb, Anna Margolin, Fradl Shtok, and Yankev Glatshteyn. Yiddish editors fought major anti-censorship Supreme Court cases during this period, playing a key role in the transnational struggle for a free press. The talk concludes by tracing how the earlier Proletarian poets deeply informed the work of later, experimental Modernist writers. Anna Elena Torres is an Assistant Professor of Comparative Literature at the University of Chicago. Her forthcoming book is titled Any Minute Now The World Streams Over Its Border!: Anarchism and Yiddish Literature (Yale University Press). This project examines the literary production, language politics, and religious thought of Jewish anarchist movements from 1870 to the present in Moscow, Tel Aviv, London, Buenos Aires, New York City, and elsewhere. Torres’ work has appeared in Jewish Quarterly Review, In geveb, Nashim, make/shift, and the anthology Feminisms in Motion: A Decade of Intersectional Feminist Media (AK Press, 2018). -

Who Was Emma Goldman and Why Is She Important?

Comments: This paper provides an overview of Emma Goldman’s definitions of anarchy, along with an explanation of her dedication to campaigns for women’s rights and birth control. The choice of primary sources is strong. The use of specific quotations from the primary sources is done well. The overall structure of the paper lacks an argument that this then supported. The paper is also missing a conclusion. The paper also needs more historical context so that the reader can understand which periods are represented by Goldman’s life and work. Placing the primary sources into a larger historical context would also help the reader understand whether Goldman’s ideas were representative of her peer group or exceptional. More analysis of the primary sources through the Primary Source Worksheet might have helped with this end. Who was Emma Goldman and why is she important? Emma Goldman is important Comment [1]: Thesis is highlighted as required by the assignment, but the thesis does not pose a strong argument that the paper will support. because she was a forward thinker who lectured and pushed for changes in our society. She The thesis suggests a general admiration for Goldman, but does not reflect a particular pushed for changes for the minorities and women of our society. position that the primary sources would represent. Emma Goldman, a self-proclaimed anarchist, believed that anarchism was actually a good thing, not a hurtful and violent path. She argues that women emancipation, while started to Comment [2]: Phrasing? promote and free women, has in fact isolated women.1 She believed that women trafficking, or 2 prostitution, was a product of social conditions. -

Feminist Thought, Organization and Action, 1970-1983

Wesleyan University The Honors College On the Edge of All Dichotomies: Anarch@-Feminist Thought, Process and Action, 1970-1983. by Lindsay Grace Weber Class of 2009 A thesis submitted to the faculty of Wesleyan University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Degree of Bachelor of Arts with Departmental Honors in History Middletown, Connecticut April, 2009 2 CONTENTS CHAPTER PAGE Note on Terminology ................................................................................................. 3 Preface ...................................................................................................................... 5 Introduction................................................................................................................ 9 Contemporary Anarcha-Feminism............................................................................ 11 Anarch@-Feminism and Historiography .................................................................. 22 Historical Background.............................................................................................. 35 CHAPTER 1 – Anarch@-Feminist Thought, 1970-1974 .......................................... 59 CHAPTER 2 – Networking, Communications, Conferences, 1974-1979 .................. 90 CHAPTER 3 – Direct Action and Community, 1978-1983..................................... 124 CHAPTER 4 – Locating Anarch@-Feminism in the Local..................................... 164 Conclusion ............................................................................................................ -

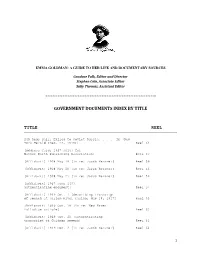

Government Documents Index by Title

EMMA GOLDMAN: A GUIDE TO HER LIFE AND DOCUMENTARY SOURCES Candace Falk, Editor and Director Stephen Cole, Associate Editor Sally Thomas, Assistant Editor GOVERNMENT DOCUMENTS INDEX BY TITLE TITLE REEL 249 Reds Sail, Exiled to Soviet Russia. In [New York Herald (Dec. 22, 1919)] Reel 64 [Address Card, 1917 July? for Mother Earth Publishing Association] Reel 57 [Affidavit] 1908 May 18 [in re: Jacob Kersner] Reel 56 [Affidavit] 1908 May 20 [in re: Jacob Kersner] Reel 56 [Affidavit] 1908 May 21 [in re: Jacob Kersner] Reel 56 [Affidavit] 1917 June 1[0? authenticating document] Reel 57 [Affidavit] 1919 Oct. 1 [describing transcript of speech at Harlem River Casino, May 18, 1917] Reel 63 [Affidavit] 1919 Oct. 18 [in re: New Haven Palladium article] Reel 63 [Affidavit] 1919 Oct. 20 [authenticating transcript of Goldman speech] Reel 63 [Affidavit] 1919 Dec. 2 [in re: Jacob Kersner] Reel 64 1 [Affidavit] 1920 Feb. 5 [in re: Abraham Schneider] Reel 65 [Affidavit] 1923 March 23 [giving Emma Goldman's birth date] Reel 65 [Affidavit] 1933 Dec. 26 [in support of motion for readmission to United States] Reel 66 [Affidavit? 1917? July? regarding California indictment of Alexander Berkman (excerpt?)] Reel 57 Affirms Sentence on Emma Goldman. In [New York Times (Jan. 15, 1918)] Reel 60 Against Draft Obstructors. In [Baltimore Sun (Jan. 15, 1918)] Reel 60 [Agent Report] In re: A.P. Olson (or Olsson)-- Anarchist and Radical, New York, 1918 Aug. 30 Reel 61 [Agent Report] In re: Abraham Schneider--I.W.W., St. Louis, Mo. [19]19 Oct. 14 Reel 63 [Agent Report In re:] Abraham Schneider, St.