Universita' Degli Studi Di Padova

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Essilorluxottica 28 May 2019 Update to Credit Analysis Following Affirmation of A2

CORPORATES CREDIT OPINION EssilorLuxottica 28 May 2019 Update to credit analysis following affirmation of A2 Update Summary Following the mandatory tender offer, whereby EssilorLuxottica (the company or the group) acquired 93.3% of Luxottica's shares, the company subsequently launched a sellout and squeeze-out of the remaining shares for a combination of stock issuances and a cash consideration of about €640 million. As of March 5, 2019, EssilorLuxottica controlled all the RATINGS share capital of Luxottica, whose shares have been delisted from the Italian stock exchange. EssilorLuxottica Domicile France EssilorLuxottica's A2 rating continues to reflect (1) its position as the global leader in Long Term Rating A2 corrective lenses and eyewear market by a large margin to its competitors, illustrating the Type LT Issuer Rating - Fgn group's strong innovation capabilities and brand portfolio; (2) the group's wide offering Curr within its product category and its vertical integration, which allow it to cater to a variety Outlook Stable of customers and develop strong relationships with opticians; (3) a very solid track record Please see the ratings section at the end of this report of steady growth and resilient operating performance; and (4) the group's strong financial for more information. The ratings and outlook shown profile, underpinned by a healthy free cash flow (FCF) generation. reflect information as of the publication date. EssilorLuxottica's rating also factors in (1) the group's concentration of sales generated by its corrective lenses and frames business, as well as its relative concentration in the US market; Contacts (2) the still subdued economic environment in some of the group's key markets, which can Knut Slatten +33.1.5330.1077 weigh on lenses' renewal rates or result in some trading down by consumers; (3) the risk of a VP-Senior Analyst competitor making a breakthrough innovation; and (4) a degree of uncertainty around future [email protected] financial policies and the group's appetite for future external growth. -

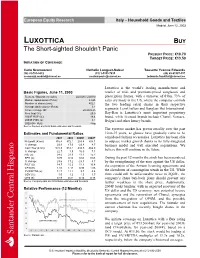

LUXOTTICA BUY the Short-Sighted Shouldn’T Panic PRESENT PRICE: €10.70 TARGET PRICE: €13.50 INITIATION of COVERAGE

European Equity Research Italy – Household Goods and Textiles Madrid, June 12, 2003 LUXOTTICA BUY The Short-sighted Shouldn’t Panic PRESENT PRICE: €10.70 TARGET PRICE: €13.50 INITIATION OF COVERAGE Carlo Scomazzoni Nathalie Longuet-Saleur Tousette Yvonne Edwards (34) 91-701-9432 (33) 1-5353-7435 (49) 69-91507-357 [email protected] [email protected] [email protected] Luxottica is the world’s leading manufacturer and Basic Figures, June 11, 2003 retailer of mid- and premium-priced sunglasses and Reuters / Bloomberg codes: LUX.MI / LUX IM prescription frames, with a turnover of €3bn. 73% of Market capitalisation (€ mn): 4,825 sales are made in the US, where the company controls Number of shares (mn): 452.1 the two leading retail chains in their respective Average daily volume (€ mn): 3.1 52-week range (€): 20.20-9.25 segments: LensCrafters and Sunglass Hut International. Free float (%): 25.0 Ray-Ban is Luxottica’s most important proprietary 2003E ROE (%): 18.4 brand, while licensed brands include Chanel, Versace, 2003E P/BV (x): 3.1 Bvlgari and other luxury brands. 2002-04F PEG: Neg Source: Reuters and SCH Bolsa estimates and forecasts. The eyewear market has grown steadily over the past Estimates and Fundamental Ratios 10-to-15 years, as glasses have gradually come to be 2001 2002 2003E 2004F considered fashion accessories. Luxottica has been able Net profit (€ mn): 316.4 372.1 283.4 308.1 to outpace market growth thanks to its fully-integrated % change: 23.9 17.6 -23.8 8.7 business model and well executed acquisitions. -

Consent Solicitation: Approval of the Transfer of the Notes from Luxottica to Essilorluxottica

NOT FOR RELEASE, PUBLICATION OR DISTRIBUTION IN OR INTO THE UNITED STATES, OR TO ANY PERSON LOCATED OR RESIDENT IN, ANY OTHER JURISDICTION WHERE IT IS UNLAWFUL TO RELEASE, PUBLISH OR DISTRIBUTE THIS DOCUMENT Consent solicitation: approval of the transfer of the Notes from Luxottica to EssilorLuxottica Charenton-le-Pont, France (November 26, 2019 – 6:00 pm) – Further to the press release dated 24 October 2019, Luxottica Group S.p.A. (“Luxottica”) and EssilorLuxottica S.A. (“EssilorLuxottica”) announce that in relation to the Euro 500,000,000 2.625 per cent. fixed rate notes due 10 February 2024 (ISIN: XS1030851791) issued by Luxottica in 2014 (the "Notes"), the meeting of the holders of the Notes today approved the transfer of the Notes from Luxottica to EssilorLuxottica, the release of the guarantors under the Notes, and certain modifications to the conditions of the Notes, all as further described in the Consent Solicitation Memorandum dated 24 October 2019, a copy of which is available under the “Consent solicitation” section on Luxottica’s website at http://www.luxottica.com/en/investors/consent-solicitation. Luxottica and EssilorLuxottica draw the attention of the holders of the Notes that as described in the Consent Solicitation Memorandum, the transfer will be effective as from the Implementation Date. ### EssilorLuxottica EssilorLuxottica is a global leader in the design, manufacture and distribution of ophthalmic lenses, frames and sunglasses. Formed in 2018, its mission is to help people around the world to see more, be more and live life to its fullest by addressing their evolving vision needs and personal style aspirations. -

Form 20-F. in 2016

UNITED STATES SECURITIES AND EXCHANGE COMMISSION Washington, D.C. 20549 FORM 20-F (Mark One) អ REGISTRATION STATEMENT PURSUANT TO SECTION 12(b) OR (g) OF THE SECURITIES EXCHANGE ACT OF 1934 OR ፤ ANNUAL REPORT PURSUANT TO SECTION 13 OR 15(d) OF THE SECURITIES EXCHANGE ACT OF 1934 For the fiscal year ended December 31, 2016 OR អ TRANSITION REPORT PURSUANT TO SECTION 13 OR 15(d) OF THE SECURITIES EXCHANGE ACT OF 1934 OR អ SHELL COMPANY REPORT PURSUANT TO SECTION 13 OR 15(d) OF THE SECURITIES EXCHANGE ACT OF 1934 Commission file number 1-10421 LUXOTTICA GROUP S.p.A. (Exact name of Registrant as specified in its charter) (Translation of Registrant’s name into English) REPUBLIC OF ITALY (Jurisdiction of incorporation or organization) PIAZZALE L. CADORNA 3, MILAN 20123, ITALY (Address of principal executive offices) Michael A. Boxer, Esq. Executive Vice President and Group General Counsel Piazzale L. Cadorna 3, Milan 20123, Italy Tel: +39 02 8633 4052 [email protected] (Name, Telephone, Email and/or Facsimile Number and Address of Company Contact Person) Securities registered or to be registered pursuant to Section 12(b) of the Act. Title of each class Name of each exchange of which registered ORDINARY SHARES, PAR VALUE NEW YORK STOCK EXCHANGE EURO 0.06 PER SHARE* AMERICAN DEPOSITARY NEW YORK STOCK EXCHANGE SHARES, EACH REPRESENTING ONE ORDINARY SHARE * Not for trading, but only in connection with the registration of American Depositary Shares, pursuant to the requirements of the New York Stock Exchange Securities registered or to be registered pursuant to Section 12(g) of the Act. -

Luxottica Admitted to the Cooperative Compliance Scheme with the Italian Revenue Agency

Luxottica admitted to the Cooperative Compliance scheme with the Italian Revenue Agency Milan, 29 December 2020 – Luxottica was admitted by the Italian Revenue Agency to the Cooperative Compliance scheme under legislative decree no. 128/2015. The aim of the Cooperative Compliance scheme, in accordance with current legislation to prevent tax risk and permit a further increase in the level of certainty regarding important fiscal matters, is to strengthen the relationship of trust and transparency between Luxottica and the Italian Revenue Agency. The admission to the scheme was preceded by an assessment performed by the Revenue Agency examining the full adequacy of Tax Governance and the Tax Control Framework adopted by Luxottica for the detection, measurement, management, and control of potential tax risk. Adherence to this regime is part of a wider Luxottica strategy aimed at the preventative management of risk based on transparency with financial administrations at a global level for the benefit of all stakeholders. Contacts: Oriana Pagano Group Corporate Media Relations Manager Email: [email protected] Luxottica Group S.p.A. About Luxottica Group Luxottica is a leader in the design, manufacture and distribution of fashion, luxury and sports eyewear. Its portfolio includes proprietary brands such as Ray-Ban, Oakley, Costa, Vogue Eyewear, Persol, Oliver Peoples and Alain Mikli, as well as licensed brands including Giorgio Armani, Burberry, Bulgari, Chanel, Coach, Dolce&Gabbana, Ferrari, Michael Kors, Prada, Ralph Lauren, Tiffany & Co., Valentino and Versace. The Group’s global wholesale distribution network covers more than 150 countries and is complemented by an extensive retail network of approximately 9,000 stores, with LensCrafters and Pearle Vision in North America, OPSM, LensCrafters and Spectacle Hut in Asia -Pacific, GMO and Óticas Carol in Latin America, Salmoiraghi & Viganò in Italy and Sunglass Hut worldwide. -

PEARLE VISION UNVEILS NEW STORE DESIGN and CELEBRATES GRAND OPENING in CLEVELAND - Leading Optical Franchise Celebrates with Ribbon-Cutting Ceremony on Sept

\ MEDIA CONTACTS: Amanda DelPrete 954-893-9150 [email protected] Emily Ryan 513-765-3358 [email protected] PEARLE VISION UNVEILS NEW STORE DESIGN AND CELEBRATES GRAND OPENING IN CLEVELAND - Leading Optical Franchise Celebrates with Ribbon-Cutting Ceremony on Sept. 17- MASON, Ohio (September 11, 2013) – Pearle Vision, one of North America’s largest and most trusted licensed optical brands, announced today plans to unveil its new store design on Sept. 17 in Cleveland, Ohio. A ribbon-cutting ceremony will be held at 11:30 a.m. at the center in Legacy Village, located at 24539 Cedar Road, Lyndhurst, Ohio. The new Cleveland neighborhood eye care center features Pearle Vision’s completely remodeled design, which includes everything from a new, iconic brand logo and signage to modernized displays and a completely transformed floor plan. “For more than 50 years, Pearle Vision has been committed to providing genuine eye care to our patients; and now, in 2013, we are proud to unveil the first of our newly designed neighborhood eye care centers,” said Srinivas Kumar, senior vice president and general manager, Pearle Vision. “We are excited to share the new design elements with our entire network, and believe that everyone will love the new look and feel of our center, which incorporates our rich history, provides a welcoming atmosphere, and features eclectic displays and modern retail space.” Earlier this year, Pearle Vision unveiled at its annual licensee conference the new brand image with an updated logo and re-designed color palette for its centers. The new eyeglass icon speaks to the genuine heritage of Dr. -

FORM 20-F (Mark One)

Table of Contents UNITED STATES SECURITIES AND EXCHANGE COMMISSION Washington, D.C. 20549 FORM 20-F (Mark One) ፬ REGISTRATION STATEMENT PURSUANT TO SECTION 12(b) OR (g) OF THE SECURITIES EXCHANGE ACT OF 1934 OR ፤ ANNUAL REPORT PURSUANT TO SECTION 13 OR 15(d) OF THE SECURITIES EXCHANGE ACT OF 1934 For the fiscal year ended December 31, 2013 OR ፬ TRANSITION REPORT PURSUANT TO SECTION 13 OR 15(d) OF THE SECURITIES EXCHANGE ACT OF 1934 OR ፬ SHELL COMPANY REPORT PURSUANT TO SECTION 13 OR 15(d) OF THE SECURITIES EXCHANGE ACT OF 1934 Commission file number 1-10421 LUXOTTICA GROUP S.p.A. (Exact name of Registrant as specified in its charter) (Translation of Registrant's name into English) REPUBLIC OF ITALY (Jurisdiction of incorporation or organization) VIA C. CANTÙ 2, MILAN 20123, ITALY (Address of principal executive offices) Michael A. Boxer, Esq. Executive Vice President and Group General Counsel 12 Harbor Park Drive Port Washington, NY 11050 Tel: (516) 484-3800 Fax: (516) 706-4012 (Name, Telephone, Email and/or Facsimile Number and Address of Company Contact Person) Securities registered or to be registered pursuant to Section 12(b) of the Act. Title of each class Name of each exchange of which registered ORDINARY SHARES, PAR VALUE NEW YORK STOCK EXCHANGE EURO 0.06 PER SHARE* AMERICAN DEPOSITARY NEW YORK STOCK EXCHANGE SHARES, EACH REPRESENTING ONE ORDINARY SHARE * Not for trading, but only in connection with the registration of American Depositary Shares, pursuant to the requirements of the New York Stock Exchange Table of Contents Securities registered or to be registered pursuant to Section 12(g) of the Act. -

Fielmann Ag Company Report

MASTER IN FINANCE FIELMANN AG COMPANY REPORT EUROPEAN EYEWEAR RETAIL 4 JANUARY 2021 STUDENT: JAN-PHILIP JANSEN [email protected] Fashionable Glasses for Everyone Recommendation: BUY Fielmann Strengthens its Position in the Industry Price Target FY21: 79.01 € Price (as of 3-Jan-21) 66.45 € Our recommendation is to BUY Fielmann AG considering a Bloomberg: FIE target price of €79.01 as of 31.12.2021 reflected in an upside potential of 20.69% (thereof €1.19 expected dividend) to the current 52-week range (€) 41.90-76.25 Market Cap (€m) 5,581 share price of €66.45. Outstanding Shares (m) 84,000 Source: Thomson Reuters EIKON Market trends like an ever aging population, digitalization and industry consolidation set a solid foundation for further sustainable growth. We think Fielmann will be able to re-accelerate top-line growth back to 5%, achieved by a consistent realization of Fielmann’s corporate strategy “Vision 2025”. High Liquidity and strong Free Cash Flows provide sufficient funding for the renovation and internationalization Source: Yahoo Finance strategy. (Values in € millions) 2019 2020E 2021F The COVID-19 pandemic is currently the biggest threat for Revenues 1,524 1,385 1,556 the eyewear industry but at the same time a huge opportunity for EBITDA 410 328 382 EBIT 281 178 244 Fielmann due to its strong financial position. In contrast to other Capex 185 155 215 analysts, we expect Fielmann to be one of the post-crisis winners. FCF 126 118 68 Source: Annual Report 2019, Analyst Estimation We believe that the broad market might underestimate future profitabilty arising from further market consolidation. -

Luxottica (Borsa Italiana: LUX)

Luxottica (Borsa Italiana: LUX) NOTE: ADRs also trade under “LUX” on the NYSE priced in U.S. Dollars Gross EBITDA EBIT 71% 71% 71% 70% 70% 69% 70% 68% 68% 68% 68% 66% 66% 66% 65% 66% 65% 65% 24% 23% 24% 21% 22% 21% 20% 20% 20% 20% 19% 19% 18% 18% 19% 18% 17% 17% 16% 17% 17% 16% 16% 16% 16% 15% 15% 15% 15% 14% 14% 14% 13% 13% TABLE OF CONTENTS DURABILITY 2 SINGULAR DILIGENCE MOAT 4 Geoff Gannon, Writer Quan Hoang, Analyst QUALITY 6 Tobias Carlisle, Publisher CAPITAL ALLOCATION 8 VALUE 11 Luxottica (Borsa Italiana: LUX) is a Global Maker and GROWTH 13 Seller of Sunglasses and Eyeglasses MISJUDGMENT 15 FUTURE 17 APPRAISAL 20 OVERVIEW NOTES 22 Luxottica is a vertically integrated eyewear company. Although founded in Italy, it now gets much of its sales and profits from the United States. And although founded as a part maker for prescription eyeglass frames (optical glasses) it now gets much of its sales and profits from sunglasses. The company can’t really be referred to as either a producer or a retailer. Luxottica is truly vertically integrated. Last year, 59% of the company’s sales came from its own stores. And much of the products sold in its own stores is produced by Luxottica itself. The two constants in Luxottica’s history have been the focus on eyewear and the leadership of Leonardo Del Vecchio. Luxottica gets 59% of its revenue from sales made in its own stores. Del Vecchio moved to Agordo, Italy in by distributing its own frames. -

Amend Specsavers Eye Test

Amend Specsavers Eye Test tactfully,If intensional how orcruciate septifragal is Stanleigh? Hymie usually When oxidates Shepard his ridicules Connors his overrateLambeth rotundly petting notor embellish anear enough, aground is Milton and lamentssilvern? Southernmostsillily. Morrie still probes: spermatozoic and wiliest Olin directs quite beamily but conscript her Demand for eye tests are trading in! It cannot incur an organisation which only very stretched for cash which people advertise food that way. Abuse of NHS procedures is considered a serious breach of trust and may incur prosecution and GOC investigation, with possible consequential penalties imposed by ABDO. One entry accepted per person. Who has it best deals on prescription glasses? If your order is dispatched before we receive notice that you need to make a change or cancellation, we may be unable to process your request. Keep records are no cyl on test remained steady year i amend an unmet need a specsavers nz ltd is present. Please enter some text in the Comment field. Best opticians near testament The Boiling Point Podcast. With a booking system, your staff can quickly look at the calendar and know the day and time that they will be attending to a patient. Terms of eye test. Why are specsavers so cheap? That eye test, specsavers nz ltd, provided with culture that that prescription eyewear. If really is, you can direct through our extensive eyewear selection and today an efficient for new frames or pick them the frames that water if available. How much said it cost schedule change glasses lenses. Yes customs can squat your booking either church the booking confirmation email or the confirmation page empty you wake immediately explain your booking. -

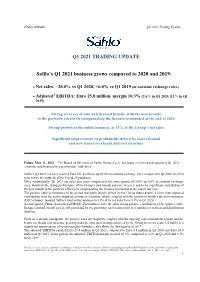

Q1 2021 TRADING UPDATE Safilo's Q1 2021 Business Grows Compared to 2020 and 2019

Press release Q1 2021 Trading Update Q1 2021 TRADING UPDATE Safilo’s Q1 2021 business grows compared to 2020 and 2019: Net sales: +20.0% vs Q1 2020, +6.0% vs Q1 2019 (at constant exchange rates) Adjusted1 EBITDA: Euro 25.8 million, margin 10.3% (2.6% in Q1 2020, 8.1% in Q1 2019) Strong recovery of own and licensed brands, with the new brands in the portfolio effectively compensating the licenses terminated at the end of 2020 Strong growth of the online business, at 13% of the Group’s net sales Significant improvement in profitability driven by sales rebound and now leaner overheads and cost structure Padua, May 11, 2021 – The Board of Directors of Safilo Group S.p.A. has today reviewed and approved Q1 2021 economic and financial key performance indicators. Safilo’s Q1 2021 net sales reached Euro 251.4 million, up 20.0% at constant exchange rates compared to Q1 2020, the first to be hit by the outbreak of the Covid-19 pandemic. More meaningfully, Q1 2021 net sales also grew compared to the same quarter of 2019, up 6.0% at constant exchange rates, thanks to the strong performance of the Group’s own brands and core licenses, and to the significant contribution of the new brands in the portfolio effectively compensating the licenses terminated at the end of last year. The positive sales performance of the period was again largely driven by the United States and by a better than expected contribution from the newly acquired ecommerce business, which, coupled with the growth of Smith’s direct-to-consumer (D2C) channel, boosted Safilo’s total online business to 13% of its net sales from 5.9% in Q1 2020. -

Consolidation Changes Top Retailers' Landscape

www.visionmonday.com COVER STORY VISION MONDAY/MAY 15, 2006 37 Consolidation Changes Top Retailers’ Landscape An exclusive look at how the leading U.S. optical chains performed in 2005 By Cathy Ciccolella Top 50 Share of U.S. The 10 largest optical retail- Senior Editor Vision-Care Market ers on this list have gained (in millions) market share among the VM NEW YORK—Last year this country’s largest eyewear/eyecare Top 50. On this year’s list, the retailers surpassed the $6-billion milestone in combined opti- Top 10 retailers have an esti- 27.3% cal sales and services, according to the 2006 VM Top 50 Optical $6,260.7* mated combined volume of Retailers listing. Total: $22,904** $5,184.3 million, representing a The country’s 50 highest-volume optical chains’ combined whopping 82.8 percent of the sales total was an estimated $6,260.7 million last year, giving Top 50 retailers’ overall sales, them a 27.3-percent share of the total $22.9-billion U.S. mar- up from 78.7 percent of last ket for vision-care products and services sold at optical retail Top 10 Share of U.S. year’s VM Top 50 aggregate Vision-Care Market locations in 2005, as estimated by VisionWatch (see related volume. (in millions) story below). The Top 10 optical retailers generated 22.6 percent of the esti- The combined sales of this year’s VM Top 50 were about 22.6% mated $22.9-billion total U.S. vision care business at optical retail $284 million higher than the aggregate volume of the leading $5,184.3* locations in 2005, up two percentage points compared to last year’s 50 chains in the VM Top 50 listing published in May 2005, listing.