On Burgenland Croatian Isoglosses Peter

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

On Burgenland Croatian Isoglosses Peter

Dutch Contributions to the Fourteenth International Congress of Slavists, Ohrid: Linguistics (SSGL 34), Amsterdam – New York, Rodopi, 293-331. ON BURGENLAND CROATIAN ISOGLOSSES PETER HOUTZAGERS 1. Introduction Among the Croatian dialects spoken in the Austrian province of Burgenland and the adjoining areas1 all three main dialect groups of central South Slavic2 are represented. However, the dialects have a considerable number of characteris- tics in common.3 The usual explanation for this is (1) the fact that they have been neighbours from the 16th century, when the Ot- toman invasions caused mass migrations from Croatia, Slavonia and Bos- nia; (2) the assumption that at least most of them were already neighbours before that. Ad (1) Map 14 shows the present-day and past situation in the Burgenland. The different varieties of Burgenland Croatian (henceforth “BC groups”) that are spoken nowadays and from which linguistic material is available each have their own icon. 5 1 For the sake of brevity the term “Burgenland” in this paper will include the adjoining areas inside and outside Austria where speakers of Croatian dialects can or could be found: the prov- ince of Niederösterreich, the region around Bratislava in Slovakia, a small area in the south of Moravia (Czech Republic), the Hungarian side of the Austrian-Hungarian border and an area somewhat deeper into Hungary east of Sopron and between Bratislava and Gyǡr. As can be seen from Map 1, many locations are very far from the Burgenland in the administrative sense. 2 With this term I refer to the dialect continuum formerly known as “Serbo-Croatian”. -

Language Policy and Linguistic Reality in Former Yugoslavia and Its Successor States

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Tsukuba Repository Language Policy and Linguistic Reality in Former Yugoslavia and its Successor States 著者 POZGAJ HADZ Vesna journal or Inter Faculty publication title volume 5 page range 49-91 year 2014 URL http://doi.org/10.15068/00143222 Language Policy and Linguistic Reality in Former Yugoslavia and its Successor States Vesna POŽGAJ HADŽI Department of Slavistics Faculty of Arts University of Ljubljana Abstract Turbulent social and political circumstances in the Middle South Slavic language area caused the disintegration of Yugoslavia and the formation of new countries in the 1990s, and this of course was reflected in the demise of the prestigious Serbo-Croatian language and the emergence of new standard languages based on the Štokavian dialect (Bosnian, Croatian, Serbian and Montenegrin). The Yugoslav language policy advocated a polycentric model of linguistic unity that strived for equal representation of the languages of the peoples (Serbo-Croatian, Macedonian and Slovenian), ethnicities (ethnic minorities) and ethnic groups, as well as both scripts (Latin and Cyrillic). Serbo-Croatian, spoken by 73% of people in Yugoslavia, was divided into the eastern and the western variety and two standard language expressions: Bosnian and Montenegrin. One linguistic system had sociolinguistic subsystems or varieties which functioned and developed in different socio-political, historical, religious and other circumstances. With the disintegration of Yugoslavia, the aforementioned sociolinguistic subsystems became standard languages (one linguistic system brought forth four political languages). We will describe the linguistic circumstances of the newly formed countries after 1991 in Croatia, Serbia, Bosnia and Herzegovina, and Montenegro. -

Stota Obljetnica Smrti Slikara Miroslava Kraljevića

MJESEČNA REVIJA HRVATSKE MATICE ISELJENIKA BROJ / NO. 1-2 MONTHLY MAGAZINE OF THE CROATIAN HERITAGE FOUNDATION SIJEČANJ-VELJAČA / JANUARY-FEBRUARY 2014. Stota obljetnica smrti slikara Miroslava Kraljevića ISSN 1330-2140 ISSN Posjetite stranice web portala Hrvatske matice iseljenika! Mjesečna revija HRVATSKE MATICE ISELJENIKA / www.matis.hr Monthly magazine of the Croatian Heritage Foundation Godište / Volume LXIV Broj / No. 1-2/2014 Nakladnik / Publisher Hrvatska matica iseljenika / Croatian Heritage Foundation Za nakladnika / For Publisher Marin Knezović Glavni urednik / Chief Editor Hrvoje Salopek Uredništvo / Editorial Staff Željka Lešić, Vesna Kukavica Tajnica / Secretary Snježana Radoš Dizajn i priprema / Layout & Design Krunoslav Vilček Tisak / Print Znanje, Zagreb Web stranice HRVATSKA MATICA ISELJENIKA Trg Stjepana Radića 3, pp 241 HMI čitaju se diljem 10002 Zagreb, Hrvatska / Croatia Telefon: +385 (0)1 6115-116 Telefax: +385 (0)1 6110-933 svijeta, dostupne su na tri www.matis.hr jezika (hrvatski, engleski, MJESEČNA REVIJA HRVATSKE MATICE ISELJENIKA BROJ / NO. 1-2 MONTHLY MAGAZINE OF THE CROATIAN HERITAGE FOUNDATION SIJEČANJ-VELJAČA / JANUARY-FEBRUARY 2014. španjolski) i bilježe stalan porast posjećenosti. Stota obljetnica smrti slikara Miroslava Kraljevića Budite korak ispred ostalih i predstavite se hrvatskim iseljeničkim zajednicama, uglednim poslovnim Hrvatima u svijetu i njihovim partnerima. Oglašavajte na web portalu ISSN 1330-2140 ISSN Hrvatske matice iseljenika! Internet marketing HMI osmislio je nekoliko načina oglašavanja: -

Centrope Location Marketing Brochure

Invest in opportunities. Invest in centrope. Central European Region Located at the heart of the European Union, centrope is a booming intersection of four countries, crossing the borders of Austria, the Czech Republic, Slovakia and Hungary. The unique mixture of sustained economic growth and high quality of life in this area offers tremendous opportunities for investors looking for solid business. A stable, predictable political and economic situation. Attractive corporate tax rates. A highly qualified workforce at reasonable labour costs. World-class infrastruc- ture. A rich cultural life based on shared history. Beautiful landscapes including several national parks. And much more. The centrope region meets all expectations. meet opportunities. meet centrope. Vibrant Region Roughly six and a half million people live in the Central European Region centrope. The position of this region at the intersection of four countries and four languages is reflected in the great variety of its constituent sub-regions and cities. The two capitals Bratislava and Vienna, whose agglomerations – the “twin cities” – are situated at only 60 kilometres from each other, Brno and Győr as additional cities of supra-regional importance as well as numerous other towns are the driving forces of an economically and culturally expanding European region. In combination with attractive landscapes and outdoor leisure opportunities, centrope is one of Europe’s most vibrant areas to live and work in. Population (in thousands) Area (in sq km) Absolute % of centrope Absolute % of centrope South Moravia 1,151.7 17.4 7,196 16.2 Győr-Moson-Sopron 448.4 6.8 4,208 9.5 Vas 259.4 3.9 3,336 7.5 Burgenland 284.0 4.3 3,965 8.9 Lower Austria 1,608.0 24.3 19,178 43.1 Vienna 1,698.8 25.5 414 0.9 Bratislava Region 622.7 9.3 2,053 4.6 Trnava Region 561.5 8.5 4,147 9.3 centrope 6,634.5 44,500 EU-27 501,104.2 4,403,357 Source: Eurostat, population data of 2010. -

The Future of the Protestant Church: Estimates for Austria and for the Provinces of Burgenland, Carinthia and Vienna

WWW.OEAW.AC.AT VIENNA INSTITUTE OF DEMOGRAPHY WORKING PAPERS 02/2020 THE FUTURE OF THE PROTESTANT CHURCH: ESTIMATES FOR AUSTRIA AND FOR THE PROVINCES OF BURGENLAND, CARINTHIA AND VIENNA ANNE GOUJON AND CLAUDIA REITER DEMOGRAPHY OF INSTITUTE Vienna Institute of Demography Austrian Academy of Sciences VIENNA – Vordere Zollamtsstraße 3| 1030 Vienna, Austria [email protected] | www.oeaw.ac.at/vid VID Abstract Secularization and migration have substantially affected the place of the Protestant Church in the Austrian society in the last decades. The number of members has been shrinking markedly from 447 thousand members in 1971 to 278 thousand in 2018. The trend is visible across all provinces, although the magnitude is stronger in Vienna where both disaffiliation and international migration are stronger: In the capital city, the Protestant population diminished from 126 thousand to 47 thousand over the 1971-2018 period. Using population projections of membership to the Protestant Church, we look at the potential future of affiliation to the Protestant Church in Austria, and in three provinces: Burgenland, Carinthia, and Vienna from 2018 to 2048, considering different paths of fertility and disaffiliation. We also look at the impact of different scenarios regarding the composition of international migration flows on affiliation to the Protestant Church. Our findings suggest that in the absence of compensatory flows, the Protestant Church will keep shrinking unless it manages to stop disaffiliation. The projections also show that migrants, especially within mobile Europe, are a potential source of members that is at present not properly contributing to membership in Austria. According to the TREND EUROPE scenario, which is – seen from today – the most likely scenario with a continuation of declining entries and increased exits, the Protestant population in Austria would still decline from 283 thousand in 2018 to 144 thousand in 2048 (-49%). -

The Impact the Collapse of the Habsburg Monarchy by Michaela and Prof

The impact the collapse of the Habsburg Monarchy By Michaela and Prof. Dr. Karl Vocelka (Article from: “Wine in Austria: The History”) The end of the First World War in 1918 produced profound consequences for Central Europe, affecting every sphere of activity within the region, ranging from high-level political decisions to the everyday lives of the inhabitants. The outcome of the ‘great seminal catastrophe of this (20th) century’ (George F. Kennan) had long-term consequences, which endure to the present day. The Second World War of 1939–1945, the Cold War that persisted in Europe until 1989, as well as the creation and expansion of the European Union are all inseparable from developments that occurred during and immediately after the Great War. A significant influence was also exerted – in an international context – on viticulture in Austria, which provides us with our current subject. This was brought about by a new world order of nation states, including the establishment of the Republic of German-Austria on 12 November 1918, on territory formerly ruled by the Habsburg Monarchy. Although the dissolution of the multinational Habsburg Empire had begun before the end of the war, a final line was not drawn until two peace agreements were concluded in the Parisian suburbs in 1919. The borders of the new Republic of Austria were set out in the Treaty of Saint- Germain-en-Laye on 10 September 1919.1 The country’s border with Hungary was established by the subsequent Treaty of Trianon in 1920.2 The victorious powers forbade the planned union with Germany and prohibited use of the name German-Austria. -

Austrian Federalism in Comparative Perspective

CONTEMPORARY AUSTRIAN STUDIES | VOLUME 24 Bischof, Karlhofer (Eds.), Williamson (Guest Ed.) • 1914: Aus tria-Hungary, the Origins, and the First Year of World War I War of World the Origins, and First Year tria-Hungary, Austrian Federalism in Comparative Perspective Günter Bischof AustrianFerdinand Federalism Karlhofer (Eds.) in Comparative Perspective Günter Bischof, Ferdinand Karlhofer (Eds.) UNO UNO PRESS innsbruck university press UNO PRESS innsbruck university press Austrian Federalism in ŽŵƉĂƌĂƟǀĞWĞƌƐƉĞĐƟǀĞ Günter Bischof, Ferdinand Karlhofer (Eds.) CONTEMPORARY AUSTRIAN STUDIES | VOLUME 24 UNO PRESS innsbruck university press Copyright © 2015 by University of New Orleans Press All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form, or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopy, recording, or any information storage nd retrieval system, without prior permission in writing from the publisher. All inquiries should be addressed to UNO Press, University of New Orleans, LA 138, 2000 Lakeshore Drive. New Orleans, LA, 70148, USA. www.unopress.org. Printed in the United States of America Book design by Allison Reu and Alex Dimeff Cover photo © Parlamentsdirektion Published in the United States by Published and distributed in Europe University of New Orleans Press by Innsbruck University Press ISBN: 9781608011124 ISBN: 9783902936691 UNO PRESS Publication of this volume has been made possible through generous grants from the the Federal Ministry for Europe, Integration, and Foreign Affairs in Vienna through the Austrian Cultural Forum in New York, as well as the Federal Ministry of Economics, Science, and Research through the Austrian Academic Exchange Service (ÖAAD). The Austrian Marshall Plan Anniversary Foundation in Vienna has been very generous in supporting Center Austria: The Austrian Marshall Plan Center for European Studies at the University of New Orleans and its publications series. -

Austria's Burgenland I August 1959

INSTITUTE OF CURRENT "WORLD AFFAIRS DR-23 Vierma Between Two Worlds: II, Obere Donaustrasse 57/1/6 Austria's Burgenland I August 1959 Mr. Walter S. Rogers Institute of Current World Affairs 68 adison Avenue New York 17, N.Y. Dear r. Rogers" The Burgenland is historically nd geographically unlikely: m misshapen strlngbean of a country, one hundred miles from north to south, 38 miles wide at its widest, but squeezed in the middle by a political trick that left it 2.5 miles wide at Sieg- graben. It cuts a curious figure on the map nd reminds one of the rches of medieval Europe, territorial frontiers creted as buffers against national enemies Scots, L.oors, or Avars, And that is, in fct, its function. For the-Burgenland (which-means "Land. of Fortresses") divides the western world from Communi st "HUngary, and its estern border comprises the entire Hungarian Iron Curtain. Again, as in the dys when its castles were built, it is a frontier land, standing guard duty for Jestern Christendom against an lien, pagan East. Nowhere is this feeling more overpowering than in one of its ancient fortresses,, first built against the ,lagyars and later manned a. galnst the Turks. The oa.stle at Gissing, in the far south, dtes xm the 12th entury an ssume its present form.in the 16th, when the Burgenland and its djolning plains were ll of Pannonia that had been sved from the Ottomans. Last week I stood inits Rittersal the Knight's Hall and peered through powerful binoculars far out across the Hungarian plain, while Ludwig Nemeth, curator of the castle, named the Hungarian villages to me -and pointed out the brbed wire, the minefields and the wooden watchtowers, on the other side of the border. -

Distr. GENERAL E/CN.4/1994/72 13 December 1993 ENGLISH Original

Distr. GENERAL E/CN.4/1994/72 13 December 1993 ENGLISH Original: ARABIC/CHINESE/ ENGLISH/FRENCH COMMISSION ON HUMAN RIGHTS Fiftieth session Item 18 of the provisional agenda RIGHTS OF PERSONS BELONGING TO NATIONAL OR ETHNIC, RELIGIOUS AND LINGUISTIC MINORITIES Report prepared by the Secretary-General pursuant to Commission on Human Rights resolution 1993/24 CONTENTS Page INTRODUCTION . 2 I. REPLIES SUBMITTED BY GOVERNMENTS Austria . 4 Benin . 9 Chad . 11 China . 12 Finland . 14 Germany . 16 Greece . 16 Hungary . 19 Jordan . 23 Norway . 23 Romania . 27 Ukraine . 27 Yugoslavia . 34 II. REPLY FROM A NON-GOVERNMENTAL ORGANIZATION International Federation for the Protection of the Rights of Ethnic, Religious, Linguistic and Other Minorities . 40 GE.93-85832 (E) E/CN.4/1994/72 page 2 INTRODUCTION 1. At its forty-ninth session, on 5 March 1993, the Commission on Human Rights adopted resolution 1993/24, entitled "Rights of persons belonging to national or ethnic religious and linguistic minorities". 2. In paragraph 1 of that resolution, the Commission called upon all States to promote and give effect as appropriate to the principles contained in the Declaration on the Rights of Persons Belonging to National or Ethnic, Religious and Linguistic Minorities adopted by the General Assembly. 3. In paragraph 2 of the same resolution, the Commission urged all treaty bodies and special representatives, special rapporteurs and working groups of the Commission on Human Rights and the Sub-Commission on Prevention of Discrimination and Protection of Minorities -

Contribution by the Austrian Länder Burgenland, Lower Austria, Upper Austria and Vienna to the EU Strategy

Contribution by the Austrian Länder Burgenland, Lower Austria, Upper Austria and Vienna to the EU Strategy for the Danube Region 07.12.2009 Overall editorial coordination: Kurt Puchinger, Magistrat der Stadt Wien Otto Frey, Magistrat der Stadt Wien Contact persons in the involved Austrian Länder: wHR Dr. Heinrich Wedral, Amt der Burgenländischen Landesregierung [email protected] Peter de Martin, Amt der Niederösterreichischen Landesregierung [email protected] Dipl.-Ing. Robert Schrötter, Amt der Oberösterreichischen Landesregierung [email protected] Dipl.-Ing. Dr. Kurt Puchinger, Amt der Wiener Landesregierung [email protected] Contents 1 EU Strategy for the Danube Region............................................................................................ 5 1.1 Context......................................................................................................................................................... 5 1.2 Objectives of an EU Strategy for the Danube Region ..................................................................................... 5 2 The Danube Region in the Limelight .......................................................................................... 6 2.1 Definition and Affiliation.............................................................................................................................. 6 2.2 Transnational Development Issues of Special Significance for Austria............................................................ 6 2.2.1 The Danube Region -

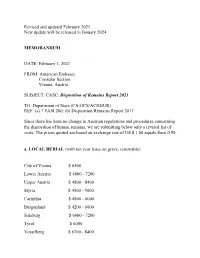

Disposition of Remains Report 2021

Revised and updated February 2021 New update will be released in January 2024 MEMORANDUM DATE: February 1, 2021 FROM: American Embassy Consular Section Vienna, Austria SUBJECT: CASC: Disposition of Remains Report 2021 TO: Department of State (CA/OCS/ACS/EUR) REF: (a) 7 FAM 260; (b) Disposition Remains Report 2017 Since there has been no change in Austrian regulations and procedures concerning the disposition of human remains, we are submitting below only a revised list of costs. The prices quoted are based on exchange rate of US $ 1.00 equals Euro 0.90. a. LOCAL BURIAL (with ten year lease on grave, renewable) City of Vienna $ 6500 Lower Austria $ 4800 - 7200 Upper Austria $ 4800 - 8400 Styria $ 4200 - 5000 Carinthia $ 4800 - 6000 Burgenland $ 4200 - 6000 Salzburg $ 6000 - 7200 Tyrol $ 6000 Vorarlberg $ 6700 - 8400 b. PREPARATION OF REMAINS FOR SHIPMENT TO THE UNITED STATES Vienna $ 6000 Lower Austria $ 6000 - 8900 Upper Austria $ 6000 - 8400 Styria $ 6000 - 8400 Carinthia $ 4800 - 6000 Burgenland $ 4800 - 7200 Salzburg $ 6000 Tyrol $ 6000 Vorarlberg $ 8900 c. COST OF SHIPPING PREPARED REMAINS TO THE UNITED STATES East Coast $ 2900 South Coast $ 2900 Central $ 2900 West Coast $ 3200 Shipping costs are based on an average weight of the casket with remains to be 150 kilos. d. CREMATION AND LOCAL BURIAL OF URN Vienna $ 5800 Lower Austria $ 9000 Upper Austria $ 3400 - 6700 Styria $ 4200 - 5000 Carinthia $ 5000 Burgenland $ 4200 - 5900 Salzburg (city) $ 4200 - 5900 Salzburg (province) $ 5500 Tyrol $ 5900 Vorarlberg $ 8400 e. CREMATION AND SHIPMENT OF URN TO THE UNITED STATES Vienna $ 3600 Lower Austria $ 4800 Upper Austria $ 3600 Styria $ 3600 Carinthia $ 4800 Burgenland $ 4800 Salzburg $ 3600 Tyrol $ 4200 Vorarlberg $ 6000 e. -

Reference Document on the Histories of Minoritisation in Austria, Hungary, Netherlands, Portugal, Turkey and The

Reference document on the histories of minoritisation in Austria, Hungary, Netherlands, Portugal, Turkey and the United Kingdom Authors Bridget Anderson, Sara Araújo, Laura Brito, Mehmet Ertan, Jing Hiah, Trudie Knijn, Isabella Meier, Julia Morris and Maddalena Vivona Editors Emma Newcombe and Liam Lemkin Anderson This Working Paper was written within the framework of Work Package 5 (justice as lived experience) for Deliverable 5.2 (comparative report on institutionalised political justice and experienced (mis)recognition) July 2018 Funded by the Horizon 2020 Framework Programme of the European Union Want to learn more about what we are working on? Visit us at: Website: https://ethos-europe.eu Facebook: www.facebook.com/ethosjustice/ Blog: www.ethosjustice.wordpress.com Twitter: www.twitter.com/ethosjustice Hashtag: #ETHOSjustice Youtube: www.youtube.com/ethosjustice European Landscapes of Justice (web) app: http://myjustice.eu/ This publication has been produced with the financial support of the Horizon 2020 Framework Programme of the European Union. The contents of this publication are the sole responsibility of the authors and can in no way be taken to reflect the views of the European Commission. Copyright © 2018, ETHOS consortium – All rights reserved ETHOS project The ETHOS project has received funding from the European Union’s Horizon 2020 research and innovation programme under grant agreement No. 727112 2 About ETHOS ETHOS - Towards a European THeory Of juStice and fairness, is a European Commission Horizon 2020 research project