URBANITIES Journal of Urban Ethnography

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Informal Settlements and Squatting in Romania: Socio-Spatial Patterns and Typologies

HUMAN GEOGRAPHIES – Journal of Studies and Research in Human Geography 7.2 (2013) 65–75. ISSN-print: 1843–6587/$–see back cover; ISSN-online: 2067–2284–open access www.humangeographies.org.ro (c) Human Geographies —Journal of Studies and Research in Human Geography (c) The author INFORMAL SETTLEMENTS AND SQUATTING IN ROMANIA: SOCIO-SPATIAL PATTERNS AND TYPOLOGIES Bogdan Suditua*, Daniel-Gabriel Vâlceanub a Faculty of Geography, University of Bucharest, Romania b National Institute for Research and Development in Constructions, Urbanism and Sustainable Spatial Development URBAN-INCERC, Bucharest, Romania Abstract: The emergence of informal settlements in Romania is the result of a mix of factors, including some social and urban planning policies from the communist and post-communist period. Squatting was initially a secondary effect of the relocation process and demolition of housing in communist urban renewal projects, and also a voluntary social and hous- ing policy for the poorest of the same period. Extension and multiple forms of informal settlements and squatting were performed in the post-communist era due to the inappropriate or absence of the legislative tools on urban planning, prop- erties' restitution and management, weak control of the construction sector. The study analyzes the characteristics and spatial typologies of the informal settlements and squatters in relationship with the political and social framework of these types of housing development. Key words: Informal settlements, Squatting, Forced sedentarization, Illegal building, Urban planning regulation. Article Info: Manuscript Received: October 5, 2013; Revised: October 20, 2013; Accepted: November 11, 2013; Online: November 20, 2013. Context child mortality rates and precarious urban conditions (UN-HABITAT, 2003). -

SPACE RESEARCH in POLAND Report to COMMITTEE

SPACE RESEARCH IN POLAND Report to COMMITTEE ON SPACE RESEARCH (COSPAR) 2020 Space Research Centre Polish Academy of Sciences and The Committee on Space and Satellite Research PAS Report to COMMITTEE ON SPACE RESEARCH (COSPAR) ISBN 978-83-89439-04-8 First edition © Copyright by Space Research Centre Polish Academy of Sciences and The Committee on Space and Satellite Research PAS Warsaw, 2020 Editor: Iwona Stanisławska, Aneta Popowska Report to COSPAR 2020 1 SATELLITE GEODESY Space Research in Poland 3 1. SATELLITE GEODESY Compiled by Mariusz Figurski, Grzegorz Nykiel, Paweł Wielgosz, and Anna Krypiak-Gregorczyk Introduction This part of the Polish National Report concerns research on Satellite Geodesy performed in Poland from 2018 to 2020. The activity of the Polish institutions in the field of satellite geodesy and navigation are focused on the several main fields: • global and regional GPS and SLR measurements in the frame of International GNSS Service (IGS), International Laser Ranging Service (ILRS), International Earth Rotation and Reference Systems Service (IERS), European Reference Frame Permanent Network (EPN), • Polish geodetic permanent network – ASG-EUPOS, • modeling of ionosphere and troposphere, • practical utilization of satellite methods in local geodetic applications, • geodynamic study, • metrological control of Global Navigation Satellite System (GNSS) equipment, • use of gravimetric satellite missions, • application of GNSS in overland, maritime and air navigation, • multi-GNSS application in geodetic studies. Report -

Disrupting Doble Desplazamiento in Conflict Zones

Disrupting Doble Desplazamiento in Conflict Zones: Alternative Feminist Stories Cross the Colombian-U.S. Border Tamera Marko, Emerson College Preface ocumentary film has the power to carry the stories and ideas of an Dindividual or group of people to others who are separated by space, economics, national boundaries, cultural differences, life circumstances and/or time. Such a power—to speak and be heard by others—is often exactly what is missing for people living in poverty, with little or no access to the technologies or networks necessary to circulate stories beyond their local communities. But bound up in that power is also a terrible responsibility and danger: how does the documentarian avoid becoming the story (or determining the story) instead of acting as the vehicle to share the story? How does she avoid becoming a self-appointed spokesperson for the poor or marginalized? Or how does he not leverage the story of others’ suffering for one’s own gain or acknowledgment? These questions become even thornier when intersected with issues of race, cultural capital, and national identity. One 9 might ask all of these questions to our next author, Tamera Marko, a U.S. native, white academic who collects video stories of displaced poor residents of Medellin, Colombia. How does she do this ethically, in a way that performs a desired service within the communities that she works, without speaking for them or defining their needs? Her article, which follows, is a testament to that commitment. Marko’s life’s work (to call it scholarship seems too small a word) resides within a complex politics of representation, and she directly takes on issues that others might shy away from. -

Slum Upgrading Strategies and Their Effects on Health and Socio-Economic Outcomes

Ruth Turley Slum upgrading strategies and Ruhi Saith their effects on health and Nandita Bhan Eva Rehfuess socio-economic outcomes Ben Carter A systematic review August 2013 Systematic Urban development and health Review 13 About 3ie The International Initiative for Impact Evaluation (3ie) is an international grant-making NGO promoting evidence-informed development policies and programmes. We are the global leader in funding, producing and synthesising high-quality evidence of what works, for whom, why and at what cost. We believe that better and policy-relevant evidence will make development more effective and improve people’s lives. 3ie systematic reviews 3ie systematic reviews appraise and synthesise the available high-quality evidence on the effectiveness of social and economic development interventions in low- and middle-income countries. These reviews follow scientifically recognised review methods, and are peer- reviewed and quality assured according to internationally accepted standards. 3ie is providing leadership in demonstrating rigorous and innovative review methodologies, such as using theory-based approaches suited to inform policy and programming in the dynamic contexts and challenges of low- and middle-income countries. About this review Slum upgrading strategies and their effects on health and socio-economic outcomes: a systematic review, was submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements of SR2.3 issued under Systematic Review Window 2. This review is available on the 3ie website. 3ie is publishing this report as received from the authors; it has been formatted to 3ie style. This review has also been published in the Cochrane Collaboration Library and is available here. 3ie is publishing this final version as received. -

Pride and Prejudice : Lesbian Families in Contemporary Sweden

Pride and Prejudice Lesbian Families in Contemporary Sweden Anna Malmquist Linköping Studies in Arts and Science No. 642 Linköping Studies in Behavioural Science No. 191 Linköping University Department of Behavioural Sciences and Learning Linköping 2015 Linköping Studies in Arts and Science No. 642 Linköping Studies in Behavioural Science No. 191 At the Faculty of Arts and Science at Linköping University, research and doctoral studies are carried out within broad problem areas. Research is organized in interdisciplinary research environments and doctoral studies mainly in graduate schools. Jointly, they publish the series Linköping Studies in Arts and Science. This thesis comes from the Division of Psychology at the Department of Behavioural Sciences and Learning. Distributed by: Department of Behavioural Sciences and Learning Linköping University SE - 581 83 Linköping Anna Malmquist Pride and Prejudice: Lesbian Families in Contemporary Sweden Cover painting: Kristin Winander Upplaga 1:1 ISBN 978-91-7519-087-7 ISSN 0282-9800 ISSN 1654-2029 ©Anna Malmquist Department of Behavioural Sciences and Learning, 2015 Printed by: LiU-tryck, Linköping 2015 To my children, Emil, Nils, Myran and Tove Färgen på barns ögon kommer från arvet, glittret i barns ögon kommer från miljön. The colour of children’s eyes comes from nature, the sparkle in children’s eyes comes from nurture. Abstract Options and possibilities for lesbian parents have changed fundamentally since the turn of the millennium. A legal change in 2003 enabled a same-sex couple to share legal parenthood of the same child. An additional legal change, in 2005, gave lesbian couples access to fertility treatment within public healthcare in Sweden. -

Regularización De Asentamientos Informales En América Latina

Informe sobre Enfoque en Políticas de Suelo • Lincoln Institute of Land Policy Regularización de asentamientos informales en América Latina E d é s i o F E r n a n d E s Regularización de asentamientos informales en América Latina Edésio Fernandes Serie de Informes sobre Enfoque en Políticas de Suelo El Lincoln Institute of Land Policy publica su serie de informes “Policy Focus Report” (Enfoque en Políticas de Suelo) con el objetivo de abordar aquellos temas candentes de política pública que están en relación con el uso del suelo, los mercados del suelo y la tributación sobre la propiedad. Cada uno de estos informes está diseñado con la intención de conectar la teoría con la práctica, combinando resultados de investigación, estudios de casos y contribuciones de académicos de diversas disciplinas, así como profesionales, funcionarios de gobierno locales y ciudadanos de diversas comunidades. Sobre este informe Este informe se propone examinar la preponderancia de asentamientos informales en América Latina y analizar los dos paradigmas fundamentales entre los programas de regularización que se han venido aplicando —con resultados diversos— para mejorar las condiciones de estos asentamientos. El primero, ejemplificado por Perú, se basa en la legalización estricta de la tenencia por medio de la titulación. El segundo, que posee un enfoque mucho más amplio de regularización, es el adoptado por Brasil, el cual combina la titulación legal con la mejora de los servicios públicos, la creación de empleo y las estructuras para el apoyo comunitario. En la elaboración de este informe, el autor adopta un enfoque sociolegal para realizar este análisis en el que se pone de manifiesto que, si bien las prácticas locales varían enormemente, la mayoría de los asentamientos informales en América Latina transgrede el orden legal vigente referido al suelo en cuanto a uso, planeación, registro, edificación y tributación y, por lo tanto, plantea problemas fundamentales de legalidad. -

Owner's Manual. Mini Hardtop 2 Door / 4 Door

LINK: CONTENT & A-Z OWNER'S MANUAL. MINI HARDTOP 2 DOOR / 4 DOOR. Online Edition for Part no. 01402667083 - VI/19 Online Edition for Part no. 01402667083 - VI/19 WELCOME TO MINI. OWNER'S MANUAL. MINI HARDTOP 2 DOOR / 4 DOOR. Thank you for choosing a MINI. The more familiar you are with your vehicle, the better control you will have on the road. We therefore strongly suggest: Read this Owner's Manual before starting off in your new MINI. It contains important information on vehicle operation that will help you make full use of the technical features available in your MINI. The manual also contains information designed to enhance operating reliability and road safety, and to contribute to maintaining the value of your MINI. Any updates made after the editorial deadline can be found in the appendix of the printed Owner's Manual for the vehicle. Get started now. We wish you driving fun and inspiration with your MINI. 3 Online Edition for Part no. 01402667083 - VI/19 TABLE OF CONTENTS NOTES Information............................................................................................................................10 QUICK REFERENCE Entering..................................................................................................................................20 Set-up and use.......................................................................................................................23 On the road........................................................................................................................... -

Campamentos: Factores Socioespaciales Vinculados a Su Persisitencia

UNIVERSIDAD DE CHILE FACULTAD DE ARQUITECTURA Y URBANISMO ESCUELA DE POSTGRADO MAGÍSTER EN URBANISMO CAMPAMENTOS: FACTORES SOCIOESPACIALES VINCULADOS A SU PERSISITENCIA ACTIVIDAD FORMATIVA EQUIVALENTE PARA OPTAR AL GRADO DE MAGÍSTER EN URBANISMO ALEJANDRA RIVAS ESPINOSA PROFESOR GUÍA: SR. JORGE LARENAS SALAS SANTIAGO DE CHILE OCTUBRE 2013 ÍNDICE DE CONTENIDOS Resumen 6 Introducción 7 1. Problematización 11 1.1. ¿Por qué Estudiar los Campamentos en Chile si Hay una Amplia Cobertura 11 de la Política Habitacional? 1.2. La Persistencia de los Campamentos en Chile, Hacia la Formulación de 14 una Pregunta de Investigación 1.3. Objetivos 17 1.4. Justificación o Relevancia del Trabajo 18 2. Metodología 19 2.1. Descripción de Procedimientos 19 2.2. Aspectos Cuantitativos 21 2.3. Área Geográfica, Selección de Campamentos 22 2.4. Aspectos Cualitativos 23 3. Qué se Entiende por Campamento: Definición y Operacionalización del 27 Concepto 4. El Devenir Histórico de los Asentamientos Precarios Irregulares 34 4.1. Callampas, Tomas y Campamentos 34 4.2. Los Programas Específicos de las Últimas Décadas 47 5. Campamentos en Viña del Mar y Valparaíso 55 5.1. Antecedentes de los Campamentos de la Región 55 5.2. Descripción de la Situación de los Campamentos de Viña del Mar y Valparaíso 60 1 5.3. Una Mirada a los Campamentos Villa Esperanza I - Villa Esperanza II y 64 Pampa Ilusión 6. Hacia una Perspectiva Explicativa 73 6.1. Elementos de Contexto para Explicar la Permanencia 73 6.1.1. Globalización y Territorio 73 6.1.2. Desprotección e Inseguridad Social 79 6.1.3. Nueva Pobreza: Vulnerabilidad y Segregación Residencial 84 6.2. -

Planning, Development and Community: Transformation of the Gecekondu Settlements in Turkey

Planning, Development and Community: Transformation of the Gecekondu Settlements in Turkey Burcu Şentürk PhD University of York Department of Politics October 2013 Abstract This thesis aims to investigate changes in gecekondu (slum house) communities through exploring the lives of three generations of rural migrants in Turkey. It suggests that the dynamic relation between their strategies and development policies in Turkey has had a large impact on the urban landscape, urban reforms, welfare policies and urban social movements. I followed qualitative research methodology, and was extensively influenced by feminist theory. Participant observation, in-depth interviews and focus group methods were used flexibly to reflect the richness of gecekondu lives. The data includes 83 interviews, one focus group and my observations in Ege neighbourhood in Ankara. First-generation rural migrants largely relied on kin and family networks and established gecekondu communities which provided them with shelter against the insecurities of urban life and their exclusion from the mainstream. The mutual trust within gecekondu communities was a result of their solidarity and collective struggle to obtain title deeds and infrastructure services. The liberalization of the Turkish economy immediately after the coup d’état in 1980 brought in Gecekondu Amnesties which legalized the gecekondus built before 1985 and fragmented labour market, resulting in a fragmentation among them in terms of gecekondu ownership, types of jobs and the scope of their resources. Since their interests were no longer the same in the face of development policies, their solidarity decreased and collective strategies were replaced by individual tactics. The dissolving of the sense of community was most visible in the area of urban transformation projects, which were based on legal ownership of houses and social assistance, and created new tensions in the 2000s. -

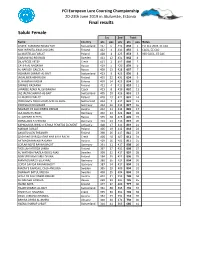

FCI European Lure Coursing 2019 Total Results.Xlsx

FCI European Lure Coursing Championship 20‐23th June 2019 in Jõulumäe, Estonia Final results Saluki Female 1st2nd Total Name Country pts pos pts pts pos Notes CHAYA' ASMAANII NESSA'YAH Switzerland 417 6 441 858 1 FCI ECC 2019, EE CAC NOX INFINITA ANAS DISCORS Finland 422 3 433 855 2 CACIL, EE CAC LA MARTELLA FARLAT Poland 428 1 425 853 3 RES‐CACIL, EE CAC GARAMIYAS ROUNAQ Sweden 411 12 431 842 4 DILAFROZE YRTEP Czech 423 2 417 840 5 CATIFA AL NAQAWA Russia 419 5 420 839 6 AL NAFISEH CALEELA Russia 409 15 428 837 7 INSHIRAH SHARAF‐AL‐BAIT Switzerland 413 9 423 836 8 JAISALMER ABHIRUCHI Finland 403 22 431 834 9 EL HAMRAH NADIIR Estonia 409 14 425 834 10 ZARABIS RAZAANA Finland 421 4 412 833 11 LARABEE AZADI AL DJIIBAAJAH Czech 413 8 419 832 12 JAZ JALIYA SHARAF‐AL‐BAIT Switzerland 405 20 426 831 13 LA MAREA FARLAT Poland 410 13 421 831 14 PIROUHETE PARU‐SIYATI‐MIN AL ASIFE Netherland 414 7 417 831 15 PADESAH FEROÚZADE Germany 413 10 414 827 16 NASIRAH OF FALCONERS DREAM Austria 412 11 414 826 17 JAA´BANU EL RIAD Germany 402 24 422 824 18 AL NAFISEH ELEEZA Russia 395 28 425 820 19 OONA‐ZIVA Y‐SHIRVAN Germany 403 23 416 819 20 KAPADOKIJA WIND CHERGUI PENKTAS ELEMENT Lithuania 408 17 411 819 21 MARAM FARLAT Poland 406 19 412 818 22 AAVATUULEN THEANOR Finland 398 26 417 815 23 QASHANG DAR QUADAR HAR KALA RACHI Czech 406 18 407 813 24 AR´MAGHAAN ALIYA KIANA Austria 409 16 402 811 25 CEYLAN NEFIZ RAVAN BACHT Germany 391 31 417 808 26 TAZILLAH AFROZA LAMIA Finland 397 27 411 808 27 AL WATHBA FAAZILA OBI EL‐MAS Sweden 390 32 417 807 28 NON SERVIAM -

German Economic Policy and Forced Labor of Jews in the General Government, 1939–1943 Witold Wojciech Me¸Dykowski

Macht Arbeit Frei? German Economic Policy and Forced Labor of Jews in the General Government, 1939–1943 Witold Wojciech Me¸dykowski Boston 2018 Jews of Poland Series Editor ANTONY POLONSKY (Brandeis University) Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data: the bibliographic record for this title is available from the Library of Congress. © Academic Studies Press, 2018 ISBN 978-1-61811-596-6 (hardcover) ISBN 978-1-61811-597-3 (electronic) Book design by Kryon Publishing Services (P) Ltd. www.kryonpublishing.com Academic Studies Press 28 Montfern Avenue Brighton, MA 02135, USA P: (617)782-6290 F: (857)241-3149 [email protected] www.academicstudiespress.com This publication is supported by An electronic version of this book is freely available, thanks to the support of libraries working with Knowledge Unlatched. KU is a collaborative initiative designed to make high quality books Open Access for the public good. The Open Access ISBN for this book is 978-1-61811-907-0. More information about the initiative and links to the Open Access version can be found at www.knowledgeunlatched.org. To Luba, with special thanks and gratitude Table of Contents Acknowledgements v Introduction vii Part One Chapter 1: The War against Poland and the Beginning of German Economic Policy in the Ocсupied Territory 1 Chapter 2: Forced Labor from the Period of Military Government until the Beginning of Ghettoization 18 Chapter 3: Forced Labor in the Ghettos and Labor Detachments 74 Chapter 4: Forced Labor in the Labor Camps 134 Part Two Chapter -

Security of Tenure: Legal and Judicial Aspects”

“Security of Tenure: Legal and Judicial Aspects” Research Paper prepared for the Special Rapporteur on adequate housing as a component of the right to an adequate standard of living and on the right to non-discrimination in this context, Raquel Rolnik, to inform her Study on Security of Tenure By Bret Thiele,1 Global Initiative for Economic, Social and Cultural Rights 1 This research paper was prepared for an expert group meeting convened by the Special Rapporteur on 22-23 October 2012, on security of tenure. The Special Rapporteur thanks Mr Bret Thiele for his contribution. Summary National laws and policies protect various elements of security of tenure, although rarely in a comprehensive manner. Security of tenure is generally implicit in many of these laws and policies, with the notable exception of laws dealing with eviction protections and regularization, which often have explicit references to security of tenure. These protections can be found in both civil and common law jurisdictions and some have been informed by international norms to various degrees, again most notably in the context of eviction protection. Forced evictions, however, continue to occur in all parts of the world and what security of tenure exists is all too often correlated with a property rights regime or socio-economic status – thus leaving marginalized individuals, groups and community most vulnerable to violations of their tenure status. Indeed, even within the same type of tenure, the degree of security of tenure often correlates to economic status. Consequently, marginalized groups are often at a disadvantage both between and amongst types of tenure.