Parliaments in the Digital Age

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Programmatic Political Competition in Latin America: Recognizing the Role Played by Political Parties in Determining the Nature of Party-Voter Linkages

Programmatic Political Competition in Latin America: Recognizing the Role Played by Political Parties in Determining the Nature of Party-Voter Linkages A Dissertation SUBMITTED TO THE FACULTY OF UNIVERSITY OF MINNESOTA BY Kevin Edward Lucas IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY David J. Samuels October 2015 © Kevin Edward Lucas, 2015 Acknowledgements While researching and writing this dissertation, I benefited greatly from the assistance and support of a seemingly endless list of individuals. Although I extend my most sincere gratitude to every single person who in one way or another contributed to my completion of the pages that follow, I do want to single out a few individuals for their help along the way. It is very unlikely that the unexpected development of programmatic party-voter linkages in El Salvador would have made it onto my radar as a potential dissertation topic had the Peace Corps not sent me to that beautiful yet complicated country in June 2001. During the nearly five years I spent living and working in La Laguna, Chalatenango, I had the good fortune of meeting a number of people who were more than willing to share their insights into Salvadoran politics with the resident gringo . There is no question in my mind that my understanding of Salvadoran politics would be far more incomplete, and this dissertation far less interesting, without the education I received from my conversations with Concepción Ayala and family, Señor Godoy, Don Bryan (RIP), Don Salomón Serrano ( QEPD ), and the staff of La Laguna’s Alcaldía Municipal . -

The European Trust Crisis and the Rise of Populism Supplementary

The European Trust Crisis and the Rise of Populism Supplementary Online Appendix Yann Algan Sergei Guriev Sciences Po and CEPR EBRD, Sciences Po and CEPR Elias Papaioannou Evgenia Passari London Business School and CEPR Université Paris-Dauphine Abstract This supplementary online appendix consists of three parts. First, we provide summary statistics, additional sensitivity checks and further evidence. Second, we provide details and sources on the data covering regional output and unemployment, trust, beliefs, attitudes and voting statistics. Third, we provide the classification of non-mainstream political parties’ political orientation (far-right, radical-left, populist, Eurosceptic and separatist) for all countries. 1 1. Summary Statistics, Additional Sensitivity Checks, and Further Evidence 1.1 Summary Statistics Appendix Table 1 reports the summary statistics at the individual level for all variables that we use from the ESS distinguishing between the pre-crisis period (2000-08) and the post-crisis period (2009-14). Panel A looks at all questions on general trust, trust in national and supranational institutions, party identification, ideological position on the left-right scale and beliefs on the European unification issue whereas in panel B we focus on attitudes to immigration. 1.2 Additional Sensitivity Checks Appendix Table 2 looks at the relationship between employment rates and voting for anti- establishment parties. Panel A reports panel OLS estimates with region fixed effects. Panel B reports difference-in-differences estimates. In contrast to Table 4, the specifications now include a dummy that takes on the value of one for core countries (Austria, France, Norway, Sweden) and zero for the periphery countries (Bulgaria, Czech Republic, Greece, Spain, Hungary, Ireland, Slovakia). -

Of Southern Europe? Anti-Neoliberal Populisms In

Instituto de Ciencia Política A ‘LATINAMERICANIZATION’ OF SOUTHERN EUROPE? ANTI-NEOLIBERAL POPULISMS IN COMPARATIVE PERSPECTIVE por Enrico Padoan Tesis presentada al Instituto de Ciencia Política de la Pontificia Universidad Católica de Chile para optar al grado académico de Doctor Profesores Guías: Pierre Ostiguy, Manuela Caiani Comisión Informante: Carla Alberti; Juan Pablo Luna; Julia Lynch; Kenneth Roberts Junio 2018 Santiago de Chile, Chile ©2018, Enrico Padoan Ninguna parte de esta tesis puede reproducirse o transmitirse bajo ninguna forma o por ningún medio o procedimiento, sin permiso por escrito del autor. ACKNOWLEDGMENTS [Please, let me use, in this opening section, different languages (my poor English, my slightly better Spanish, and my hopefully decent Italian). I just want to speak to different people through the language (the ‘code’) that we are used to employ to talk to each other. I am aware that perhaps this is not a proper decision, and I apologize for that. I just want to thank all of you as clearly as possible]. Scorrendo i ringraziamenti di diverse tesi di dottorato, magari poi divenute libri, ho letto svariate volte la frase ‘this was not a solitary enterprise’. Questa tesi, al contrario, è davvero frutto di una solitary enterprise. Ovviamente, non nel senso che quanto scritto in queste pagine sia esclusivamente farina del mio sacco, quando invece (e lo specificherò fra non molto) è frutto di un lunghissimo processo di confronto e di dibattito con moltissimi docenti, colleghi ed amici, i quali mi hanno aiutato a migliorarne il contenuto (ovviamente, valga il caveat “gli errori e le mancanze sono miei”). -

New Latin American Left : Utopia Reborn

Barrett 00 Prelims.qxd 31/07/2008 14:41 Page i THE NEW LATIN AMERICAN LEFT Barrett 00 Prelims.qxd 31/07/2008 14:41 Page ii Transnational Institute Founded in 1974, the Transnational Institute (TNI) is an international network of activist-scholars committed to critical analyses of the global problems of today and tomorrow, with a view to providing intellectual support to those movements concerned to steer the world in a democratic, equitable and environmentally sustainable direction. In the spirit of public scholarship, and aligned to no political party, TNI seeks to create and promote international co-operation in analysing and finding possible solu- tions to such global problems as militarism and conflict, poverty and marginalisation, social injustice and environmental degradation. Email: [email protected] Website: www.tni.org Telephone + 31 20 662 66 08 Fax + 31 20 675 71 76 De Wittenstraat 25 1052 AK Amsterdam The Netherlands Barrett 00 Prelims.qxd 31/07/2008 14:41 Page iii The New Latin American Left Utopia Reborn Edited by Patrick Barrett, Daniel Chavez and César Rodríguez-Garavito Barrett 00 Prelims.qxd 31/07/2008 14:41 Page iv First published 2008 by Pluto Press 345 Archway Road, London N6 5AA www.plutobooks.com Copyright © Patrick Barrett, Daniel Chavez and César Rodríguez-Garavito 2008 The right of the individual contributors to be identified as the authors of this work has been asserted by them in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988. British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library ISBN 978 0 7453 2639 9 Hardback ISBN 978 0 7453 2677 1 Paperback Library of Congress Cataloging in Publication Data applied for This book is printed on paper suitable for recycling and made from fully managed and sustained forest sources. -

Mise En Page 1

Print ISSN: 1994-0963 Electronic ISSN: 1994-098X INTER-PARLIAMENTARY UNION CHRONICLE OF PARLIAMENTARY ELECTIONS 2009 CHRONICLE OF PARLIAMENTARY ELECTIONS VOLUME 43 Published annually in English and French since 1967, the Chronicle of Parliamentary Elections reports on all national legislative elections held throughout the world during a given year. It includes information on the electoral system, the back- ground and outcome of each election as well as statistics on the results, distri- bution of votes and distribution of seats according to political group, sex and age. The information contained in the Chronicle can also be found in the IPU's data- base on national parliaments, PARLINE. PARLINE is accessible on the IPU web site (http://www.ipu.org/parline) and is continually updated. Inter-Parliamentary Union VOLUME 43 5, chemin du Pommier Case postale 330 CH-1218 Le Grand-Saconnex Geneva – Switzerland Tel.: +41 22 919 41 50 Fax: +41 22 919 41 60 2009 E-mail: [email protected] Internet: http://www.ipu.org 2009 Chronicle of Parliamentary Elections VOLUME 43 1 January - 31 December 2009 © Inter-Parliamentary Union 2010 Print ISSN: 1994-0963 Electronic ISSN: 1994-098X Photo credits Front cover: Photo AFP/Pascal Pavani Back cover: Photo AFP/Tugela Ridley Inter-Parliamentary Union Office of the Permanent Observer of 5, chemin du Pommier the IPU to the United Nations Case postale 330 220 East 42nd Street CH-1218 Le Grand-Saconnex Suite 3002 Geneva — Switzerland New York, N.Y. 10017 USA Tel.: + 41 22 919 41 50 Tel.: +1 212 557 58 80 Fax: -

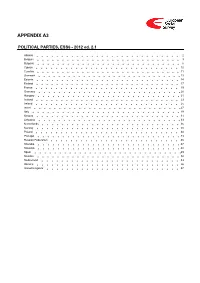

ESS6 Appendix A3 Political Parties Ed

APPENDIX A3 POLITICAL PARTIES, ESS6 - 2012 ed. 2.1 Albania 2 Belgium 3 Bulgaria 6 Cyprus 10 Czechia 11 Denmark 13 Estonia 14 Finland 17 France 19 Germany 20 Hungary 21 Iceland 23 Ireland 25 Israel 27 Italy 29 Kosovo 31 Lithuania 33 Netherlands 36 Norway 38 Poland 40 Portugal 43 Russian Federation 45 Slovakia 47 Slovenia 48 Spain 49 Sweden 52 Switzerland 53 Ukraine 56 United Kingdom 57 Albania 1. Political parties Language used in data file: Albanian Year of last election: 2009 Official party names, English 1. Partia Socialiste e Shqipërisë (PS) - The Socialist Party of Albania - 40,85 % names/translation, and size in last 2. Partia Demokratike e Shqipërisë (PD) - The Democratic Party of Albania - 40,18 % election: 3. Lëvizja Socialiste për Integrim (LSI) - The Socialist Movement for Integration - 4,85 % 4. Partia Republikane e Shqipërisë (PR) - The Republican Party of Albania - 2,11 % 5. Partia Socialdemokrate e Shqipërisë (PSD) - The Social Democratic Party of Albania - 1,76 % 6. Partia Drejtësi, Integrim dhe Unitet (PDIU) - The Party for Justice, Integration and Unity - 0,95 % 7. Partia Bashkimi për të Drejtat e Njeriut (PBDNJ) - The Unity for Human Rights Party - 1,19 % Description of political parties listed 1. The Socialist Party of Albania (Albanian: Partia Socialiste e Shqipërisë), is a social- above democratic political party in Albania; it is the leading opposition party in Albania. It seated 66 MPs in the 2009 Albanian parliament (out of a total of 140). It achieved power in 1997 after a political crisis and governmental realignment. In the 2001 General Election it secured 73 seats in the Parliament, which enabled it to form the Government. -

THE IMPACT of SOCIAL MOVEMENTS on STATE POLICY: HUMAN RIGHTS and WOMEN MOVEMENTS in ARGENTINA, CHILE and URUGUAY VOLUME I a Di

THE IMPACT OF SOCIAL MOVEMENTS ON STATE POLICY: HUMAN RIGHTS AND WOMEN MOVEMENTS IN ARGENTINA, CHILE AND URUGUAY VOLUME I A Dissertation Submitted to the Graduate School of the University of Notre Dame in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy by Cora Fernández Anderson ______________________ Frances Hagopian, Director Graduate Program in Political Science Notre Dame, Indiana December 2011 THE IMPACT OF SOCIAL MOVEMENTS ON STATE POLICY: HUMAN RIGHTS AND WOMEN MOVEMENTS IN ARGENTINA, CHILE AND URUGUAY Abstract By Cora Fernández Anderson Under what conditions does a social movement have an impact on state policy and gets their main demands addressed? This dissertation explores these questions through a structured and focused comparison of two social movements in three Latin American countries: Argentina, Chile and Uruguay. The cases analyzed in this project are the human rights movement and their demand for justice for the past abuses of the military dictatorship, and the women’s movement demand for the decriminalization of abortion from the time of each country’s democratic transition until 2007. This dissertation argues that for non bread and butter issues to be addressed by the government a social movement organized around them must be present. The movement has to be strong in terms of its power to attract supporters, since it is mainly responsible for placing the issue on the political agenda. Non-bread-and-butter issues such as those espoused by the social movements studied here are not considered a priority by public opinion in developing countries, and thus have a hard time reaching the political agenda Cora Fernández Anderson if no movement mobilizes behind them. -

EUDO CITIZENSHIP OBSERVATORY Access to Electoral Rights Uruguay

EUDO CITIZENSHIP OBSERVATORY ACCESS TO ELECTORAL RIGHTS URUGuaY Ana Margheritis June 2015 CITIZENSHIP http://eudo-citizenship.eu European University Institute, Florence Robert Schuman Centre for Advanced Studies EUDO Citizenship Observatory Access to Electoral Rights Uruguay Ana Margheritis June 2015 EUDO Citizenship Observatory Robert Schuman Centre for Advanced Studies Access to Electoral Rights Report, RSCAS/EUDO-CIT-ER 2015/7 Badia Fiesolana, San Domenico di Fiesole (FI), Italy © Ana Margheritis This text may be downloaded only for personal research purposes. Additional reproduction for other purposes, whether in hard copies or electronically, requires the consent of the authors. Requests should be addressed to [email protected] The views expressed in this publication cannot in any circumstances be regarded as the official position of the European Union Published in Italy European University Institute Badia Fiesolana I – 50014 San Domenico di Fiesole (FI) Italy www.eui.eu/RSCAS/Publications/ www.eui.eu cadmus.eui.eu Research for the EUDO Citizenship Observatory Country Reports has been jointly supported, at various times, by the European Commission grant agreements JLS/2007/IP/CA/009 EUCITAC and HOME/2010/EIFX/CA/1774 ACIT, by the European Parliament and by the British Academy Research Project CITMODES (both projects co-directed by the EUI and the University of Edinburgh). The financial support from these projects is gratefully acknowledged. For information about the project please visit the project website at http://eudo-citizenship.eu Access to Electoral Rights Uruguay Ana Margheritis 1. Introduction Uruguay has had a long-standing reputation as one of the most stable and advanced democracies in Latin America. -

Manifesto Project Dataset List of Political Parties

Manifesto Project Dataset List of Political Parties [email protected] Website: https://manifesto-project.wzb.eu/ Version 2016a from May 20, 2016 Manifesto Project Dataset - List of Political Parties Version 2016a Coverage of the Dataset including Party Splits and Merges The following list documents the parties that were coded at a specific election. The list includes the name of the party or alliance in the original language and in English, the party/alliance abbreviation as well as the corresponding party identification number. In the case of an alliance, it also documents the member parties it comprises. Within the list of alliance members, parties are represented only by their id and abbreviation if they are also part of the general party list. If the composition of an alliance has changed between elections this change is reported as well. Furthermore, the list records renames of parties and alliances. It shows whether a party has split from another party or a number of parties has merged and indicates the name (and if existing the id) of this split or merger parties. In the past there have been a few cases where an alliance manifesto was coded instead of a party manifesto but without assigning the alliance a new party id. Instead, the alliance manifesto appeared under the party id of the main party within that alliance. In such cases the list displays the information for which election an alliance manifesto was coded as well as the name and members of this alliance. 1 Manifesto Project Dataset - List of Political Parties -

CSESIII Parties and Leaders Original CSES Text Plus CCNER Additions

CSESIII Parties and Leaders Original CSES text plus CCNER additions (highlighted) =========================================================================== ))) APPENDIX I: PARTIES AND LEADERS =========================================================================== | NOTES: PARTIES AND LEADERS | | This appendix identifies parties active during a polity's | election and (where available) their leaders. | | The party labels are provided for the codes used in the | micro data variables. Parties A through F are the six | most popular parties, listed in descending order according | to their share of the popular vote in the "lowest" level | election held (i.e., wherever possible, the first segment | of the lower house). | | Leaders A through F are the corresponding party leaders or | presidential candidates referred to in the micro data items. | This appendix reports these names and party affiliations. | | Parties G, H, and I are supplemental parties and leaders | voluntarily provided by some election studies. However, | these are in no particular order. | | If parties are members of electoral blocs, the name of | the bloc is given in parentheses following the appropriate | party labels. --------------------------------------------------------------------------- >>> PARTIES AND LEADERS: AUSTRALIA (2007) --------------------------------------------------------------------------- 01. PARTY B Liberal Party John Howard 0101 Peter Costello 02. PARTY A Australian Labor Party Kevin Rudd 0201 Julia Gillard 03. PARTY C National Party Mark Vaile 0301 -

Government Composition, 1960-2015 Codebook

Codebook: Government Composition, 1960-2015 Codebook: SUPPLEMENT TO THE COMPARATIVE POLITICAL DATA SET – GOVERNMENT COMPOSITION 1960-2015 Klaus Armingeon, Virginia Wenger, Fiona Wiedemeier, Christian Isler, Laura Knöpfel and David Weisstanner The Supplement to the Comparative Political Data Set provides detailed information on party composition, reshuffles, duration, reason for termination and on the type of government for 36 democratic OECD and/or EU-member countries. The data begins in 1959 for the 23 countries formerly included in the CPDS I, respectively, in 1966 for Malta, in 1976 for Cyprus, in 1990 for Bulgaria, Czech Republic, Hungary, Romania and Slovakia, in 1991 for Poland, in 1992 for Estonia and Lithuania, in 1993 for Latvia and Slovenia and in 2000 for Croatia. In order to obtain information on both the change of ideological composition and the following gap between the new an old cabinet, the supplement contains alternative data for the year 1959. The government variables in the main Comparative Political Data Set are based upon the data presented in this supplement. When using data from this data set, please quote both the data set and, where appropriate, the original source. Please quote this data set as: Klaus Armingeon, Virginia Wenger, Fiona Wiedemeier, Christian Isler, David Weisstanner and Laura Knöpfel. 2016. Supplement to the Comparative Political Data Set – Government Composition 1960-2015. Bern: Institute of Political Science, University of Berne. Last updated: 2017-08-31 1 Codebook: Government Composition, 1960-2015 -

Freedom in the World 1989-1990 Complete Book

Freedom in the World Freedom in the World Political Rights & Civil Liberties 1989-1990 Freedom House Survey Team R. Bruce McColm Survey Coordinator James Finn Douglas W. Payne Joseph E. Ryan Leonard R. Sussman George Zarycky Freedom House Copyright © 1990 by Freedom House Printed in the United States of America. All rights reserved. No part of this book may be used or reproduced in any manner without written permission except in the case of brief quotations embodied in critical articles and reviews. For permission, write to Freedom House, 48 East 21st Street, New York, N.Y. 10010. First published in 1990. Cover design by Emerson Wajdowicz Studios, N.Y.C. The Library of Congress has cataloged this serial title as follows: Freedom in the world / —1978 New York : Freedom House, 1978 v. : map ; 25 cm.—(Freedom House Book) Annual. ISSN 0732-6610=Freedom in the World. 1. Civil rights—Periodicals. I. R. Bruce McColm, et al. II. Series. JC571.F66 323.4'05-dc 19 82-642048 AACR 2 MARC-S Library of Congress [8410] ISBN 0-932088-56-2 (pbk.) Distributed by arrangement with University Press of America, Inc. 4720 Boston Way Lanham, MD 20706 3 Henrietta Street London WC2E 8LU England Contents Foreword 1 The Comparative Survey of Freedom 1989-1990: The Challenges of Freedom 3 The Survey 1990—A Summary 8 The Map of Freedom—1990 13-15 Map Legend 17 Survey Methodology 19 The Tabulated Ratings 22 Country Reports Introduction 25 The Reports 27 Related Territories Reports 281 Tables and Ratings Table of Independent Countries—Comparative Measures of Freedom